This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Milwaukee Road (MILW) by George Drury. As with most major US railways, the Milwaukee Road was a long-term collection of different railway lines, some merged for obvious economic benefit and others taken over to reduce competition, but the first of the components that eventually evolved into the Milwaukee Road system was the 1847 Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad. This line was incorporated to connect the Wisconsin city of Milwaukee to the river traffic along the Mississippi River, and the corporate name was changed even before construction began to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad to more adequately convey the purpose of the line. The first segment opened in November 1850 connecting Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, a distance of five miles, then to Waukesha a few months later, then to Madison, but not extending all the way to the river at Prairie du Chien until 1857.

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Milwaukee Road (MILW) by George Drury. As with most major US railways, the Milwaukee Road was a long-term collection of different railway lines, some merged for obvious economic benefit and others taken over to reduce competition, but the first of the components that eventually evolved into the Milwaukee Road system was the 1847 Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad. This line was incorporated to connect the Wisconsin city of Milwaukee to the river traffic along the Mississippi River, and the corporate name was changed even before construction began to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad to more adequately convey the purpose of the line. The first segment opened in November 1850 connecting Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, a distance of five miles, then to Waukesha a few months later, then to Madison, but not extending all the way to the river at Prairie du Chien until 1857.

In that year, another of the frequent financial crises of the era struck and the company struggled on for two years, but eventually went into receivership in 1859. New owner the Milwaukee and Prairie du Chien Railroad took possession in 1861. After the Civil War, the company was merged with the Milwaukee and St. Paul and in 1874 the combined railroad became known as the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul with the completion of a new line connecting with Chicago.

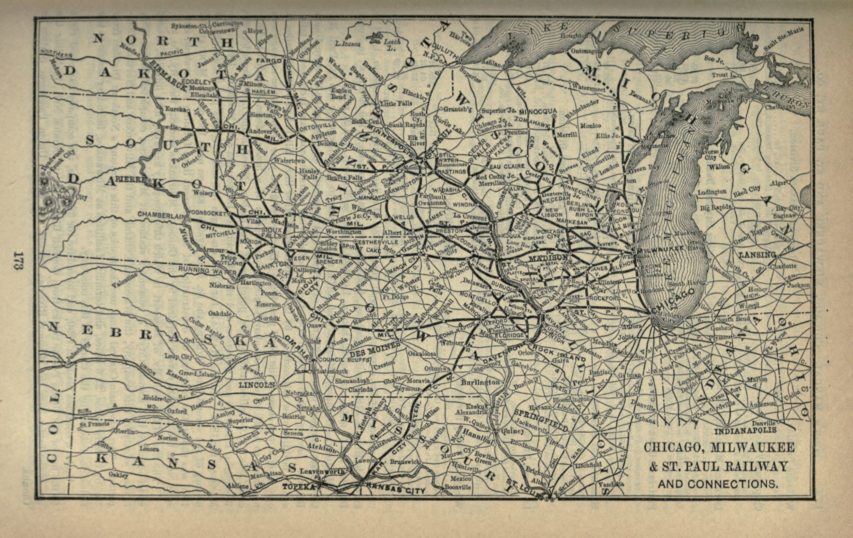

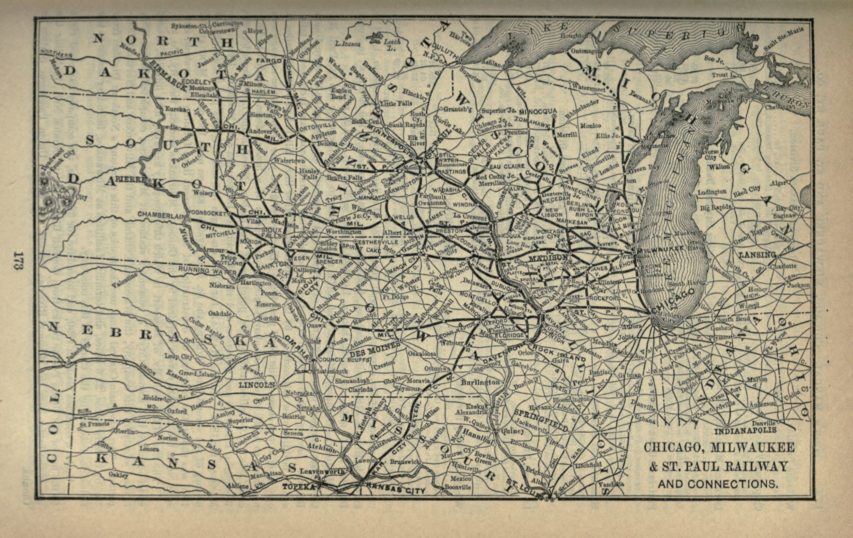

In the next few years the road built or bought lines from Racine, Wis., to Moline, Ill.; from Chicago to Savanna, Ill., and two lines west across southern Minnesota. The road reached Council Bluffs, Iowa, across the Missouri River from Omaha, in 1882, and reached Kansas City in 1887. In 1893 the CM&StP acquired the Milwaukee & Northern, which reached from Milwaukee into Michigan’s upper peninsula.

In 1900 the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul was considered one of the most prosperous, progressive, and enterprising railroads in the U.S. Its lines reached from Chicago to Minneapolis, Omaha, and Kansas City. Secondary lines and branches covered most of the area between the Omaha and Minneapolis lines in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. Lines covered much of eastern South Dakota and reached the Missouri River at three places in that state: Running Water, Chamberlain, and Evarts. Except for the last few miles into Kansas City and operation over Union Pacific rails from Council Bluffs to Omaha, the Missouri River formed the western boundary of the CM&StP. (“Milwaukee Road” as a name or nickname did not come into use until the late 1920s; “St. Paul Road” was sometimes used as a nickname, but the railroad’s advertising used the full name).

The Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway in 1893.

Poor’s Manual of the Railroads of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

The battle over control of the Northern Pacific and the Burlington in 1901 made the Milwaukee Road aware that without its own route to the Pacific it would be at its competitors’ mercy. At the same time the Milwaukee Road was experiencing a change in its traffic from dominance by wheat to a more balanced mix of agricultural and industrial products. Arguments against extension westward included the possibility of the construction of the Panama Canal and the presence of strong competing railroads: Union Pacific, Northern Pacific, and Great Northern. Arguments for the extension banked heavily on the growth of traffic to and from the Pacific Northwest.

In 1901 the president of the Milwaukee Road dispatched an engineer west to estimate the cost of duplicating Northern Pacific’s line. His figure was $45 million. Such an expenditure required considerable thought; not until November 1905 did Milwaukee’s board of directors authorize construction of a line west to Tacoma and Seattle.

In 1905 and ’06 the Milwaukee Road incorporated subsidiaries in South Dakota, Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The Washington company was renamed the Chicago, Milwaukee & Puget Sound Railway, and it took over the other three companies in 1908. It was absorbed by the CM&StP in 1912.

The extension began with a bridge across the Missouri River at Mobridge, 3 miles upstream from Evarts, S.D. Roadbed and rails pushed out from several points into unpopulated territory. The work went quickly, and the road was open to Butte, Mont., in August 1908.

Unfortunately for the Milwaukee, the Pacific extension was much more expensive to build than the initial estimates (it jumped from $45 million in the 1901 survey to $60 million in 1905), eventually weighing down the company books with $257 million in debt and worse, the traffic estimates for the new line turned out to be wildly optimistic. The difficulties of operating steam locomotives across the extension in winter pushed the railway toward electrification as an efficiency and cost-saving move. Beginning in 1914, sections of the line were converted to overhead catenary power until a total of 645 route-miles were being operated with electric locomotives, reportedly saving the company over a million dollars per year.

A Milwaukee “Little Joe” electric locomotive hauling a freight train along the Pacific extension in 1941. The “Little Joe” locomotives were originally built for the Soviet Union in the late 1940s but the US government cancelled the export license as relations with the Soviets deteriorated and the Cold War escalated. The Milwaukee Road bought 12 of the 20 from General Electric for $1 million during the Korean War.

Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the savings through electrification, the Pacific extension drove the company into bankruptcy in 1925, re-emerging as the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, but the new company also had to declare bankruptcy during the Great Depression. Trustees ran the railroad for ten years until renewed civilian traffic after World War 2 allowed normal operations to resume. As with most North American railroads, the good times didn’t last and by the late 1950s, the Milwaukee’s management were looking for a merger partner to help cut costs and shed unprofitable branch lines. Unlike the rival merger of of Northern Pacific, Great Northern, Burlington Route, and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway into Burlington Northern, the ICC blocked a merger between the Milwaukee Road and the Chicago and North Western. The ICC also blocked a later application for the Milwaukee to be included in the Union Pacific/Rock Island merger.

With declining business, deferred maintenance issues on most lines, and some self-induced financial issues caused by selling off rolling stock and leasing it back (which exacerbated car shortages leading to further reductions in business), the company had no funds to replace the failing “Little Joe” locomotives on the Pacific extension, so electrification was abandoned in 1974. George Drury sums up the mistakes that led to the end:

Over the decades, the road’s management had made too many wrong decisions: building the Pacific Extension, not electrifying between the two electrified portions, purchasing the line into Indiana, and in the 1960s choosing Flexivans (containers with separate wheels/bogies that required special flatcars) instead of conventional piggyback trailers.

After several money-losing years in the early 1970s, the Milwaukee voluntarily entered reorganization once again on December 19, 1977. The major result of the 1977 reorganization was the amputation of everything west of Miles City, Mont., to concentrate on what became known as the “Milwaukee II” system linking Chicago, Kansas City, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Duluth (on Burlington Northern rails from St. Paul), and Louisville (but no longer Omaha).

By 1983 the Milwaukee’s system consisted of the Chicago–Twin Cities main line; Chicago–Savanna–Kansas City; Chicago–Louisville (almost entirely on Conrail and Seaboard System rails), Milwaukee–Green Bay; New Lisbon–Tomahawk, Wis.; Savanna–La Crosse, along the west bank of the Mississippi; Marquette to Sheldon, Iowa, and Jackson, Minn.; Austin, Minn.–St. Paul; and St. Paul–Ortonville, Minn., plus a few branches.

Three roads vied for what remained of the Milwaukee: the Chicago & North Western, financially none too solid itself; Canadian National subsidiary Grand Trunk Western, with an eye toward creating a route between eastern and western Canada south of the Great Lakes; and Canadian Pacific subsidiary Soo Line.

Merch store ► teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals

Merch store ► teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals