Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-5-edited/1453).

This will be the last installment I’ll be re-posting here, as discussion with Alex after I obtained a copy of Marc Milner’s North Atlantic Run made it clear that the bulk of the writing up until this point had actually been copied directly from Milner’s book and only lightly paraphrased and re-ordered by Alex. I’ve gone back over the earlier posts and, to the best of my ability, marked all the direct quotes and provided acknowledgements appropriately.

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos are in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 1 — Canada’s navy before WW2

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

Part 3 — The professionals and the amateurs

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Part 6 — New ships, new challenges

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Part 9 — Early-to-mid 1941, The Rocky Isle in the Ocean

Part 10 — The Newfoundland Escort Force and the Canadian corvettes

Part 11 — “Chummy” Prentice and the NEF

Part 12 — Staff needed, training needed, and Commodore Murray’s thankless tasks

Part 13 — Convoy operations, the Americans, and 1941 Drags On

Marc Milner discusses convoy organization in North Atlantic Run:

The organization and sailing of convoys was co-ordinated by the Admiralty’s world-wide intelligence network, of which Ottawa was the North American centre. The assembling of shipping in convoy ports was the responsibility of local NCS staffs working in conjunction with the regional intelligence centre, through which all communication with other regional centres passed. The actual organization of the convoys, issuing code books, charts, special publications, arrangement of pre-sailing conferences, passing out sailing orders, and so forth, was all the work of the NCS.

[Editor’s Note: The command structure for typical Atlantic convoys is discussed in Arnold Hague’s excellent reference work The Allied Convoy System 1939-1945: Its organization, defence and operation:

In typical British fashion, control of the convoy was twofold. Direct control of the convoy rested with the Convoy Commodore, its protection with the Senior Officer of the Escort (referred to in the RN as SOE). As the escort commander was inevitably junior to the Commodore, it was laid down that the Commodore had no right of intervention with the escort, and that the SOE could, if he became aware of circumstances requiring it, give a mandatory instruction to the Commodore. A good deal of tolerance and understanding between the two officers was therefore essential. In fact, friction was minimal, co-operation normally of a high order and the whole system remarkably effective, with the Commodore dealing solely with the merchant ships of the convoy. The SOE intervened (or detailed another escort) at the specific request of the Commodore to provide any assistance required in controlling the convoy.

The divided command system should be seen in the context of the experience of the two commanders. The Commodores, all elderly men, had practical, personal, experience of the problems of coal fired ships from their younger days. As almost all had started their Commodore’s service in the first months of the war they had considerable personal experience of the problems of the Masters whom they led. The escort commanders, much younger officers, lacked that personal knowledge, and the opportunity to obtain it. The system worked in practice, with only rare cases of a personality clash between Commodore and SOE or Commodore and ships’ Masters. In such instances, the Admiralty could exercise its prerogative of dispensing with a Commodore’s services, or appointing him elsewhere. In the only case known to the writer, the offending Commodore, described as “an intolerant personality who greatly upset the Masters of ships in the convoy,” was appointed elsewhere after a short interval. He served the next five years in a single, vital appointment with distinction and great efficiency and, as the Commodore commanding the working-up base at Tobermory in Western Scotland, he was responsible for the training of all newly built or re-commissioned British escort vessels during 1940-45. Indeed not a few RCN and Allied escorts also passed through his hands. He contributed to a very large extent indeed to the efficiency of such escorts and his name became wiedly known and one to respect and admire. His name? Vice-Admiral Sir Gilbert O. Stephenson, also known as the “Terror of Tobermory”.

[…]

Convoy Commodores were drawn from a list of volunteers to serve either with Ocean or Coastal convoys. For the former, the choice was made from retired Flag Officers and Captains of the Royal Navy who were appointed as Commmodores 2nd Class in the Royal Naval Reserve for the period of their duty. … Almost every Commodore was aged over sixty when the commenced his appointment, some older, and their retired ranks varied from Admiral to Lieutenant-Commander. … Commodores for the North Atlantic routes were drawn from a pool of less than 200 who served almost exclusively in that ocean. … Russian convoys drew their Commodores from the North Atlantic pool. Convoy systems organized by the Royal Australian and Royal Canadian Navies, principally coastal, were provided with Commodores appointed by those Services.

All Commodores had the right to request reversion to non-active service at any time, while the Admiralty retained the right (and occasionally exercised it) to retire a Commodore from service.

Commodores were assisted in their duties by a Vice-Commodore and, on occasions, by one or more Rear-Commodores. A Vice-Commodore could be either a Commodore RNR from the pool serving as an assistant or the Commodore of another convoy that had joined at sea. … In all other instances the Vice- and Rear-Commodores were Masters of ships in the appropriate convoy. Their duty was to assist the Commodore and to assume his duties should he be lost during the convoy.

Commodores were accompanied by a staff: a Yeoman of Signals (a Petty Officer of the Communications Branch), three Convoy Signalmen and usually a Telegraphist. They carried considerable responsibility and were, without exception, highly efficient visual signallers. It was also usual to provide the Vice-Commodore with two Convoy Signalmen to assist him in his duties.

In large trans-Atlantic convoys the commodore sailed front and centre, usually in a large ship which was well appointed for visual and wireless communications with the rest of the convoy and equipped for direct wireless communication with shore authorities. The commodore was also the crucial link between the convoy and its escort. Although the escort commander was ultimately responsible for the safe and timely arrival of the convoy, in practice he and the commodore worked as a team. The vice- and rear-commodores, where needed, were stationed in stern positions on the outer columns of the convoy. Each had his own small staff, largely signallers. Interestingly, the majority of convoy signallers in the North Atlantic by 1941 were RCN.

Marc Milner outlines convoy routing in North Atlantic Run:

Once the convoy cleared the outer defences of the harbour, it became the responsibility of the escort forces. Its routing, however, was laid down prior to sailing by the RN’s Trade Division (shared with the USN after the American entry into the war), which prescribed a series of points of longitude and latitude through which the convoy was to pass. Minor tactical deviations within a narrow band along the convoy’s main line of advance were permitted the SOE, but major alterations of course remained the prerogative of shore authorities. The ideal routing, one towards wich the Allies moved much more slowly than they would have liked, was one simple “tramline” along the most direct course between North America and Britain — the great circle route. For a number of reasons tramlines were not feasible until 1943. For the greater portion of the period covered by this study the object of routing remained simple avoidance of the enemy, within the limits of air and sea escorts.

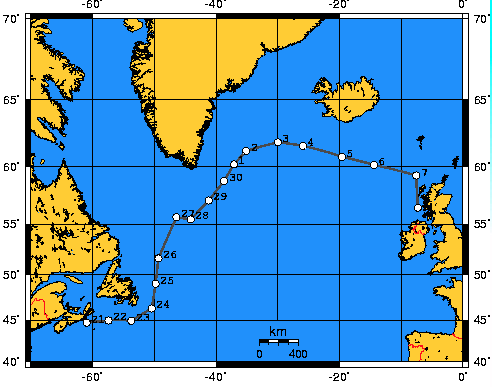

Convoy chart for convoy HX-134, departed on 20 June, 1941, arrived in Liverpool 9 July, 1941.

Image from the Convoy Web Convoy Charts page – http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/extras/index.html

The fast and slow convoy system had undergone some changes by mid-1941. Fast convoys from Halifax were still faster than 9 knots, but ships capable of moving faster than 14.8 knots were routed independently now. Slow convoys from Sydney, Cape Breton were ships capable of speeds between 7.5 and 8.9 knots. Their slow speed drew together a decrepit class of aged tramps, and there was initially no plan to convoy them through the winter. It soon became clear to the staff that all merchant shipping below a certain speed needed to be convoyed, otherwise the loss rate was far too high. For the ships and crews of the escort groups it was a thankless task: slow convoys were notorious for ill-discipline and inattention to signals. The older, slower ships were prone to excessive smoke (endangering the whole convoy by making easier to detect at a distance), breaking down, straggling (falling behind the convoy, beyond the protective screen of escorts sometimes to the point of losing contact with the convoy altogether), or even sailing ahead of the convoy “if stokers happened upon a better-than-average bunker of coal”. Slow convoys were said to more often resemble a mob than an orderly assemblage of ships, and their slow speed made evasive action difficult, if not impossible.

Unidentified signals personnel at the flag locker of the armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince David in Halifax, Nova Scotia, January 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-104500

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

By the time [Commodore] Murray arrived to take command of NEF it had grown to seven RN and six RCN destroyers, four RN sloops, and twenty-one corvettes, all but four of them RCN. The Admiralty would have liked even more committed to NEF. Indeed, in early July the Admiralty proposed to NSHQ that Halifax be virtually abandoned as an operational base and that the RCN’s main effort be concentrated at St John’s. Naval Service HQ might have expected grander British plans for St John’s when the Admiralty recommended that Commodore Murray command NEF instead of the RCN’s initial choice, Commander Mainguy. For practical reasons, however, concentrating the entire fleet at St John’s was impossible. In the summer of 1941 there were not enough facilities to support NEF, let alone the RCN’s whole expansion program, and it would be a long time before this situation was reversed. The Naval Council did not debate long before the idea was dismissed as impractical. None the less, subtle British pressure to increase the RCN’s commitment to St John’s was continued, in large part because the RN wanted to eliminate its involvement in escort operations in the Western Atlantic. In August, for example, the Admiralty advised the RCN that it preferred to deal with only one operational authority in the Western Atlantic, CCNF. The pressure, in combination with a serious German assault on convoys in NEF’s area by the late summer, proved successful. Despite growing USN involvement in convoy operations in the Western Atlantic, fully three-quarters of the RCN’s disposable strength was assigned to NEF by the end of the year. In spring of 1941, however, the RCN was unprepared to make such large-scale commitments.

One week after Murray assumed his post as CCNF, NEF fought its first convoy battle. Ironically, the confrontation was brought about by the increasing effectiveness of Allied convoy routing as a result of the penetration of the U-boat ciphers in May. Excellent evasive routing so reduced the incidence of interception that the U-boat command, out of frustration, broke up its patrol lines and scattered U-boats in loose formation. This made accurate plotting by Allied intelligence much more difficult and consequently made evasive routing less precise.

The first action against enemy submarines for the NEF occurred on the 23rd of June, 1941. Convoy HX-133 comprised fifty-eight ships eastbound from Halifax escorted by the destroyer HMCS Ottawa (SOE, Captain E.R. Mainguy) and the corvettes, HMCS Chambly, Collingwood, and Orillia. At some point during the day, the convoy was sighted by U-203, which communicated the convoy position to U-boat command and continued to shadow from a distance. U-203 attacked on the night of 23-24 June, easily penetrating the thin screen of escorts to sink a merchant ship. The SOE found it impossible to co-ordinate the escorts’ defence or to direct any search for the submarine because the corvettes were not fitted with radio telephones and their wireless sets were unable to reliably stay in communication with the SOE. Only Chambly logged receiving signals from Ottawa, but only half of them. On the 26th, Ottawa established an ASDIC contact and attacked and two of the corvettes came to assist, Commander Mainguy instructed the corvettes to stay and keep the U-boat submerged while the destroyer re-joined the convoy. The message, sent by message light, was only partially received, and the corvettes could not get the message repeated. Unable to determine what the order was, both ships broke off the action and returned to the convoy in turn. The escort group was eventually reinforced by RN ships, and although HX-133 lost six merchantmen, the RN escorts sank two of the attacking U-boats. These Canadian problems were lamentable, but hardly unexpected. As Joseph Schull, the RCN’s official historian, concluded, “no one could have expected it to be otherwise”.

Marc Milner picks up the story in North Atlantic Run:

In the meantime, Captain (D), Greenock’s stern criticism of the Canadian corvettes found its way to NSHQ, accompanied by a covering letter from Captain C.R.H. Taylor, RCN, who had succeeded Murray in London as CCCS. Taylor noted that the poor state of readiness of the corvettes stemmed from the fact that they were manned and stored for passage only. Deficiencies could not be made up from the RCN’s UK manning pool since most of the men who were committed to it were in fact still aboard the ships. Taylor also noted that the poor quality of officers, especially COs, had been pointed out in April and that they would never have been assigned if the ships had commissioned permanently. It was heartening to note, however, that Hepatica, Trillium, and Windflower, through remedial work and extra effort, were worked up “to a state of efficiency which the Commodore Western Isles reported as surpassing many RN corvettes”.

View of HMCS Annapolis from HMCS Hamilton, 30 August, 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-104149Naval Service HQ was therefore well braced when a follow-up letter from the Admiralty arrived several days later. The letter took a conciliatory view of Canadian difficulties, noting that these seemed to be “essentially similar to those occasionally experienced with the RN corvettes and trawlers”. To overcome these the Admiralty advised of three means employed by the RN. If the officers and men were competent and responsive, simply prolonging the length of work-up usually sufficed. If the officers were incompetent or otherwise unsatisfactory, they could be replaced by new ones drawn from a manning pool. Similarly, inefficient or unsuitable key ratings could be replaced by men drawn from a pool maintained for this purpose. In its concluding remarks the letter cautioned that corvettes commissioning and working up in Canada were likely to display a wide variation in efficiency, and warned that at this point, with ships stretched to provide continuous A/S escort in the North Atlantic, “no reduction in individual efficiency can be safely accepted”. This was true enough, but it contradicted what the Admiralty had said to the RCN in April, when the issue of manning the ten “British” corvettes had been resolved.

While the Admiralty clearly felt that it was offering the RCN a workable set of solutions, the suggestions contained few alternatives for the Canadians. In sum, the RCN was hard pressed just to find men with enough basic training in order to get the corvettes to sea. Producing a surplus of specialists — of any kind — was out of the question. Nelles, in his draft reply to the Admiralty, pointed out that all experienced officers and men were already committed either to new ships or to the new RCN work-up establishment, HMCS Sambro, at Halifax. Future prospects looked equally grim. Spare HSD ratings (the highest level of ASDIC operator, of which there was to be one per corvette) would not be available until the spring of 1942, a prognosis even Nelles considered optimistic. And no trained RCN commanding officers or first lieutenants could be spared for some time to come. In short, a pool of qualified and disposable personnel was out of the question. If the RN wanted to loan experienced personnel until they could be replaced by the RCN, such help would be “greatly appreciated”. The only other options were prolonged work-ups or some form of ongoing training. Aside from that, Canadian escorts had to make do. RCN escorts sent to work up at Tobermory through 1941 continued to arrive in an unready state, though here is no indication that these were any worse off than corvettes retained for work-up in Canada. The state of ships arriving in Tobermory not only resulted in “much excellent training [being] lost”; it did little to enhance the RCN’s already tattered image within the parent service.

[Editor’s Note: The training at Tobermory really was both intense and nerve-wracking for RN and RCN crews alike, as James Lamb recounts in The Corvette Navy:]

… the really soul-testing experience, the one that every old corvette type still recalls today with a shudder, came with the two-week work-ups for newly commissioned ships, designed to make a collection of odds and sods into an efficient ship’s company. There were such bases at Bermuda, St. Margaret’s Bay, and Pictou on the Canadian side, but the one that really left a lot of scar tissue was the old original, the Dante’s Inferno operated at Tobermory on the northwest coast of Scotland by the redoubtable Vice-Admiral Gilbert Stephenson, Royal Navy. This legendary character, variously known as “Puggy”, “The Lord of the Isles”, or more commonly “The Old Bastard”, inhabited a former passenger steamer, The Western Isles, which lay at anchor in the quiet, picturesque harbour, surrounded by a handful of newly commissioned corvettes, like a spider surrounded by the empty husks of its victims. He was a daunting sight, smothered in gold lace and brass buttons, with a piercing blue eye that could open an oyster at thirty paces, and tufts of grey hair sprouting from craggy cheeks, and he preyed like some ravening dragon upon the callow crews and shaky officers served up to him at fortnightly intervals.

At the end of each day, an exhausted crew would tumble into their hammocks, but there was no assurance of uninterrupted slumber. On the contrary; the monster stalked its unwary prety by dark as well as by light, and seldom a night passed without an alarm of some sort. For the Admiral delighted in midnight forays; more than one commanding officer was shaken awake to find himslef staring into the piercing eyes of a malevolent Admiral and learn that his gangway had been left unportected, that his ship had been taken, and that his kingdom had been given over to the Medes and the Persians.

But occasionally — just occasionally — the ships got a little of their own back. There was the occasion when the Admiral in his barge, lurking soundlessly under the fo’c’sle of what he hoped to be an unsuspecting frigate, waiting for the sailor whom he could hear humming to himself on the deck above to move on, suddenly found himself being urinated on, “from a great height”, as gleeful narrators related the story in a hundred rapturous wardrooms. There was the other frigate he boarded one dark night only to be set upon by a ferocious Alsatian dog and fored to leap back into his boat, leaving, in the best comic-strip tradition, a portion of his trouser-seat aboard the ship, which ever after displayed the tattered remains as a proud trophy, suitably mounted and inscribed.

And there was the Canadian corvette sailor who worsted the fiery Admiral in a hand-to-hand duel. Coming aboard this ship, the Admiral suddenly removed this cap and flung it on the deck, shouting to the astounded quartermaster: “That’s an unexploded bomb; take action, quickly now!”

With surprising sang-froid, the youngster kicked the cap over the side. “Quick thinking!” commended the Admiral. Then, pointing to the slowly sinking cap, heavy with gold lace, the Admiral continued: “That’s a man overboard; jump to it and save him!”

The ashen-faced matelot took one look at the icy November sea, then turned and shouted: “Man overboard! Away lifeboat’s crew!”

The look on the Admiral’s face, as he watched his expensive Gieves cap slowly disappear into the depths while a cursing, fumbling crew attempted to get a boat ready for lowering, was balm to the souls of all who saw it.

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

Although reports from both sides of the Atlantic indicated that the expansion fleet was badly in need of training and direction, its future looked bright in the summer of 1941. Corvettes operating from Sydney and Halifax as part of the Canadian local escort held up remarkably well to operations in the calmer months. A sampling of escorts based at Sydney in the months of August and September reveals startling statistics on the small amount of sea and out-of-service time logged by the new ships. Considerably less than half of their days were spent at sea, and this represented only about 56 percent of their seaworthy time. With so much time alongside, ships’ companies were able to keep up with teething problems. In the ships in question all time out of service was devoted to boiler cleaning. … Later, as operations crowded available time and spare hands crowded the mess decks to provide extra watches for longer voyages, the shorter period became routine. But it is significant that until the fall of 1941 the corvette fleet enjoyed considerable slack, in which it could make good its defects.

The easy routine extended to NEF as well and offered an opportunity to improve on the operational efficiency of escorts already committed to convoy duties. “As the force is now organized,” Captain E.B.K. Stevens, RN, Captain (D), Newfoundland, wrote in early September, “there is ample time for training ships, having due regard for necessary rest periods between convoy cycles.” It would be a year and a half, or more, before the same could be said again. Moreover, when the Canadian escorts did have slack time, the dearth of training equipment at St John’s was, as Stevens reported, “a beggar’s portion”; one wholly inadequate target borrowed from the United States Army and one MTU (mobile A/S training unit) bus suitable for training destroyers (although corvette crews could be and were trained on it).

Personnel preparing to fire depth charges as the destroyer HMCS Saguenay attacks a submarine contact at sea, 30 October 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-204329Captain (D)’s concern for the languishing advance to full efficiency arose from recent gunnery exercises off St John’s. “It is noticeable,” NEF’s gunnery officer reported, “that everyone from the First Lt., who is Gunnery Control Officer, downwards put their fingers to their ears each time the gun fired.” Not surprisingly, this prevented the ship’s gunnery officer from observing the fall of the shot, since he could not possibly use his glasses with his hands thus employed. In addition, some of the guns crews were startled by the firing, and all of this contributed to a deplorable rate of three rounds per minute. Captain (D) drily concluded that “At present most escorts are equipped with one weapon of approximate precision, the ram.” And so it remained for quite some time.

What NEF really needed, of course, was a proper training staff, hard and fast minimum standards for efficiency, the will to adhere to them, and improved training equipment. A tame submarine would have been a distinct advantage, but by the time L27, the submarine assigned to NEF by Western Approaches Command, arrived from Britain later in the fall, there was no time set aside for training. Throughout 1941 only hesitant and largely unsuccessful attempts were made to rectify this situation. In August, Prentice obtained permission from Murray to establish a training group for newly commissioned ships arriving from Halifax. The crews of these were found to be totally “inexperienced and almost completely untrained”. Unfortunately, as with other such attempts, Prentice’s first training group was stillborn because of increased operational demands at the end of the summer. So long as the training establishment at Halifax produced warships of such questionable quality, operations in the mid-ocean suffered, and it would be some time before the home establishments switched their emphasis from quantity to quality.

Relief for the struggling escorts of NEF was in the offing from two directions as summer gave way to autumn. By the end of August 1941 nearly fifty new corvettes were in commission, including those taken over from the RN. More were ready, at the rate of five to six per month, before the end of the year. With the men, the ships, and a little time and experience, the nightmare of jamming two years of expansion into one would be ended. This optimistic view was enhanced by the increased involvement of the USN in NEF’s theatre of operations and by the prospect that many of its responsibilities would be passed to the Americans.

The Americans had hardly been passive bystanders in the unfolding battle for the North Atlantic communications. The westward expansion of the war threatened to bring an essentially European conflict to the Western Hemisphere. Certainly, it disrupted normal trade patterns. With the establishment of American bases in Newfoundland in late 1940 that island became for the US what it was already for Canada — the first bastion of North American defence. But neither the US president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, nor American service chiefs were content to rest on the Monroe Doctrine. Moreover, aside from the purely defensive character of US involvement in Newfoundland, the Americans made an enormous moral, financial, and industrial commitment to the free movement of trade to Britain with the announcement of Lend-Lease in March 1941. A natural corollary to lend-lease was what Churchill called “constructive non-belligerency”, the American protection of US trade with Britain. While Britain would clearly have liked a more rapid involvement of the US in the Atlantic battle, American public opinion would only stand so much manipulation. Therefore, it was not until August that Roosevelt felt confident enough to meet Churchill and work out the details of American participation in the defence of shipping.

Conference leaders during Church services on the after deck of HMS Prince of Wales, in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, during the Atlantic Charter Conference. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (left) and Prime Minister Winston Churchill are seated in the foreground. Standing directly behind them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN; General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army; Admiral Harold R. Stark, USN; and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, RN. At far left is Harry Hopkins, talking with W. Averell Harriman.

US Naval Historical Center Photograph #: NH 67209 via Wikimedia Commons.A great deal has been written about Roosevelt’s and Churchill’s historic meeting at Argentia, Newfoundland, in August 1941. Here it is only important to note how the agreements directly affected the conduct and planning of RCN operations in the North Atlantic. The British and Americans decided, without consultation with Canada, that strategic direction and control of the Western Atlantic would pass to the US as per ABC 1. Convoy-escort operations west of MOMP became the responsibility of the USN’s Support Force (soon redesignated Task Force Four), with its advanced base at Argentia, Newfoundland.