Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-2-edited/1434).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Continued from Joseph Schull’s Far Distant Ships:

German infantry and armour were sweeping along the western coast of France, driving into the sea the broken fragments of British and French divisions. Here and there, at isolated bays and harbours, a few battalions of soldiers might be rescued by ship; a few hundreds out of the hundreds of thousands of refugees might be saved. Parties of engineers from England might be landed ahead of the advancing enemy to conduct vitally important demolitions. In this work the Canadian destroyers joined with many British ships.

Restigouche and St. Laurent, at sea on June 9, saw from thirty miles distant the flames of Le Havre rising six hundred feet into the night sky. On June 11 they were off St. Valéry en Caux in the neighbourhood of Dieppe, assisting the British destroyer Broke to embark wounded. Part of the British 51st Division was holding a six-mile line in the vicinity but reported itself “in no immediate need of evacuation.” St. Laurent moved a little way up the coast to Veules and took on board forty French troops. She returned to the neighbourhood of St. Valéry an hour or so later to find Restigouche and the British destroyer still standing by for evacuation.

At about eight o’clock in the morning five or six salvoes splashed into the water a hundred yards from St. Laurent and Restigouche. A German battery had taken up position on the cliffs behind the town and there was no longer any possibility of embarking troops. The three destroyers engaged the battery, although they were unable to observe the fall of their shells behind the three hundred foot cliff. When they broke off after a desultory action, Canadian ships had exchanged their first fire with the German enemy.

In North Atlantic Run, Marc Milner explains the Canadian government’s concerns about protecting the eastern seaboard, initially limiting the number of RCN ships that could be sent to European waters:

Undoubtedly the alteration of this policy owed something to the stationing at Halifax of the RN’s Third Battle Squadron, a force of aged battleships and light cruisers intended to provide anti-raider protection for mercantile convoys and more than sufficient to guarantee a credible deterrence along Canada’s Atlantic coast. The alteration of the previous policy also inaugurated the principle of loaning ships to the RN, which became “for a considerable period the dominant element of RCN policy.”

The government’s change of heart not only suited the navy’s burning desire to join in the “active operations” of more distant waters but was also perhaps a response to growing public pressure for a more active involvement in the war. In April 1940, before the invasion of Norway began, Mackenzie King confessed to his diary that the pride of the nation demanded that Canada increase its military commitment overseas from a single division to a full corps. The slow expansion of the navy could not keep up with the national desire to pick up where the Canadian Corps had left off in 1918. Even Colonel Ralston, the minister of Defence, confessed that the military involvement in the land war would have to grow, although “we could have used our money more effectively if it had been confined to air and naval matters.” Canadians, the prime minister’s private secretary wrote years after the war, remained remote from the war, “despite the very large part Canadian airmen and sailors were taking in actual combat,” until the army landed in Sicily in July 1943.

On June 21, the day of France’s humiliation at Compiègne, HMCS Fraser was sent far down the west coast near the Franco-Spanish frontier, to land a Royal Navy evacuation party and to patrol off St. Jean-de-Luz, one of the last remaining French ports unblocked by German forces (this was part of Operation Aerial, the evacuations from the west coast of France). At dawn on the 23rd she was sent north to Arcachon to pick up Canadian and South African diplomats. Transferring them from the sardine fishing boat they had escaped in was no easy task, but eventually all were delivered safely aboard and then transferred to the cruiser HMS Galatea for transport back to England. Fraser returned to St. Jean-de-Luz and was joined by Restigouche and several British destroyers. “The melancholy tumult of evacuation was now fully underway. Boatloads of defeated soldiers and destitute civilians were streaming out from the jetties to the liners, tramp steamers, trawlers and pleasure craft which jostled each other in the rough waters of the harbour. Destroyers threaded a dangerous way among the thronging ships, marshaling the loaded vessels into groups for escort to England while other destroyers zigzagged outside on anti-submarine patrol.” In the dreary 48 hours of the St. Jean-de-Luz evacuation, 16,000 soldiers escaped.

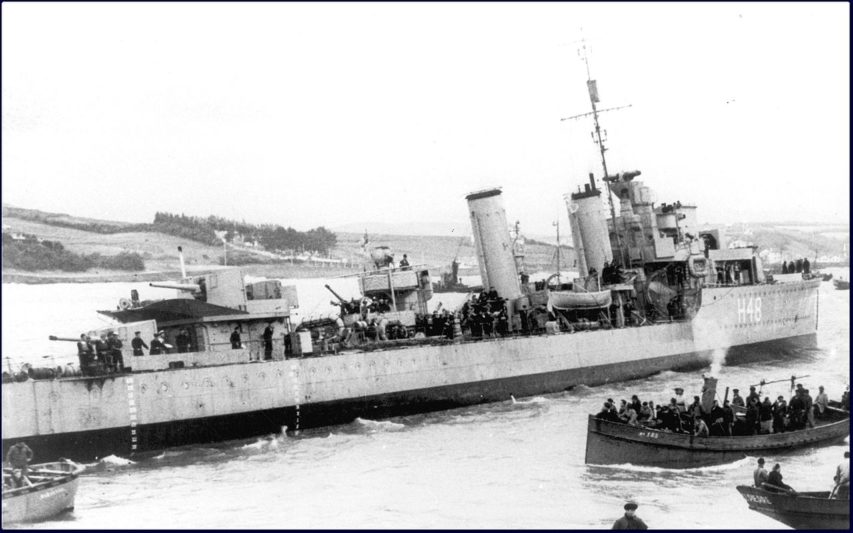

HMCS Fraser (H48), commanded by Commander W.B. Creery, on the 25th of June, 1940 off St. Jean-de-Luz, three days before her loss.

Photo from the Canadian Navy Heritage Project, via Wikimedia Commons.

Rear Admiral W.B. Creery, at the time commanding officer of the Fraser, described the final evacuation to Reader’s Digest years later:

The Germans occupied Bordeaux and swept south. By the morning of June 25th, they were within 25 miles of St. Jean-de-Luz. The French, to conform to the armistice terms, had advised that all evacuation must cease by 1 p.m. Fraser had been ordered to remain in harbour during the final evacuation but we had difficulty finding a safe anchorage. We had to re-anchor twice. on the last attempt we held firm — for a reason we were not to discover until later.

We decided to remain where we were until the return of Sub-Lieutenant William Landymore who had been sent away in our motorboat to try and persuade some Belgian trawler skippers to sail to England instead of Spain. Suddenly the officer of the watch, who had a slight stammer, exclaimed “G-G-Good G-G-God, there’s a g-g-gun!” I looked where he was pointing. On a hill a small force of soldiers had appeared with a field gun and a tank. We couldn’t make out their nationality, but ships in harbour are sitting ducks and there was only one thing to do. We ordered the merchant ships to proceed to sea and had to watch several boatloads of evacuees turn sadly back to shore. Our motorboat returned and Landymore sent the boat’s crew swarming up the falls but remained in the boat himself. I was anxious to go to action stations and weigh anchor but it took all hands to hoist the boat.

All was going reasonably well until a steadying line parted, the boat canted sharply outboard and Landymore was catapulted into the sea. Just as this happened I was told the anchor had apparently fouled a cable on the bottom of the harbour and could not be hoisted. And the officer of the watch reported that there were now “a number” of field guns on the hill and they appeared to be taking aim at us. So we fished Landymore out of the sea, slipped our cable and departed in haste if not in dignity.

The merchant ships headed for England, escorted by several RN destroyers. Fraser and Restigouche were ordered to join the British cruiser Calcutta in a sweep north in search of an enemy ship of which there had been a vague report. No such ship was found and toward dusk the flag officer turned his small force toward home.

Joseph Schull continues this particular narrative in Far Distant Ships:

It was now about ten o’clock in the evening, with a fresh breeze, a moderate swell and visibility of one and a half miles. Fraser was off the starboard bow of Calcutta a mile and a half distant, Restigouche was on the cruiser’s port quarter a mile and a half to the left of her and slightly astern. The ships were travelling at high speed, with the possibility of attack by submarine or from the air at any time. They had been in continuous action for nearly a week, carrying on rescue work and embarking troops and refugees under threat of submarine attack, air attack and every harassment of a general evacuation. Fraser‘s commanding officer had had one night’s sleep in the preceding ten and there is little likelihood that the captain of the Calcutta had had more.

As the ships steamed on, just visible to each other in the darkness, Calcutta signalled for “single line ahead” and Fraser altered course to comply. Her commanding officer’s intention was to turn inward toward Calcutta, run back down to starboard of her and come into station astern. On the cruiser’s bridge, however, when the dim silhouette of Fraser was seen altering to port ahead, the assumption was made that she intended to come across Calcutta‘s bows and pass down her port side. At the speed the ships were making, the destroyer would had had little room to cross in front; and Calcutta‘s captain therefore ordered a sharp turn to starboard; at the same time giving the order for one blast to be sounded on the siren.

The turn to starboard by the cruiser and the turn to port by the destroyer put the two ships on courses converging with fatal rapidity. Calcutta‘s signal blast for a starboard turn was Fraser‘s first warning of approaching disaster; and nothing could now be done to avert it. The vessels were swinging under helm and moving together at a combined speed of thirty-four knots. Engines were put astern and wheels reversed but no order could take effect in time. The ships covered the last two hundred yards intervening between them in less than eleven seconds and Calcutta, still swinging to starboard, sheared her way through the forward part of Fraser. The destroyer’s forepart broke clean off and floated away bottom up. Her entire bridge, with the captain and bridge personnel, was lifted onto Calcutta‘s bow and remained there, swaying and groaning above the cruiser’s forecastle.

Restigouche was in station about fifteen hundred yards astern of Calcutta. With the crash of the impact she raced up alongside Fraser and worked her way inward toward the afterpart of the broken ship. Rocking in a heavy swell which threatened to dash her against the jagged mass of steel, Restigouche brought her stern around to touch the stern of Fraser. While the hulls of the two ships ground perilously together, sixty of Fraser‘s crew, including one stretcher case, were safely transferred. For the men already in the water, Restigouche and Calcutta lowered boats, dropped carley floats and let down scramble-nets along their sides.

Fraser‘s bow had floated away, carrying the cries of its marooned occupants into the darkness. Restigouche coming up from astern, had at first mistaken it for a half-submerged wreck. When she identified it for what it was, she endeavoured to work alongside, but just as she was approaching, the bow capsized. The men clinging to the guard-rails were thrown into the water and had to be picked up by the ships’ boats. Altogether, in spite of darkness and a rising swell, 16 officers and 134 men were rescued. Forty-seven Canadians and nineteen British sailors were lost.

The River-class destroyer HMCS Restigouche, May 1942.

Canada. Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / ecopy.

Schull continues in Far Distant Ships:

The loss of Fraser, heavy blow though it was for the navy and for the homes of forty-seven Canadians, was a minor incident of those disastrous days; one of the casualties which were as certain to occur under conditions of prolonged and incessant strain as under direct shellfire. Nor could it be lingered upon. …

Skeena, Restigouche, and St. Laurent now turned with scores of British ships to a desperate battle for convoy routes through the southwestern approaches. The U-boats were beginning to arrive in greater numbers; the Luftwaffe was everywhere over the channel and far out to sea. The great ports of the south and east were under constant attack; in their scanty hours in harbour between U-boat hunts and the rescue of survivors from sunken vessels, Canadian destroyers landed men to assist in combatting air raids.

[Editor’s Note: By early July the Admiralty faced the hard decision to re-arrange the whole supply system that Britain now depended upon for food, fuel, armaments, and ammunition. The large southern and eastern ports were under bombing attack frequently enough to rule out receiving and unloading merchant convoys, without risking unacceptably high ship losses. The ports on the Mersey and Clyde rivers, being further away from German airfields, must accept the majority of the cargo from North America and elsewhere. The convoys had to be routed through the northwestern approaches, minimizing the risk of air attack. The escort vessels also had to shift to their new operational area; the remaining three Canadian destroyers in British waters would now operate from Liverpool, Greenock, Rosyth, and eventually Londonderry (where new port facilities were being hurriedly constructed).]