In Quillette, Matt Johnson discusses the phenomenon of devoted leftists being willing to criticize their own “side”, and includes a section on George Orwell’s willingness to critique leftists while still being a fully dedicated leftist himself:

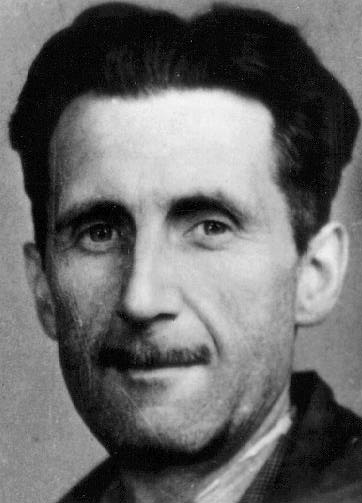

Bruckner’s remark about “Stalinist blackmail” calls to mind a writer whose commitment to both left-wing politics and anti-totalitarianism never wavered in the face of threats and coercion from the Left.

In the summer of 2003, the BBC aired George Orwell: A Life in Pictures. About halfway through the documentary, Orwell (played by Chris Langham) says, “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism.” This is a line from one of Orwell’s best-known essays, published in 1946, “Why I Write.” But astute viewers may have noticed that something was missing from the reference — eight words that the producers decided to leave out.

Here’s the original sentence: “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” After the sentence abruptly ends with the word “totalitarianism” in the documentary, Langham takes a long drag on his cigarette before jumping to a different passage of the essay. It was almost as if the producers wanted to accentuate the omission, taunting viewers with their own version of Orwell — one who didn’t have the courage to disclose his true beliefs.

There’s something simultaneously fitting and perverse about the manipulation of Orwell’s words more than half a century after his death (by the BBC, no less). Orwell’s anxiety about the falsification of history is one of the major themes of Nineteen Eighty-Four — as well as much of his other writing and later correspondence — and this is what the producers of the documentary were guilty of doing when they amputated one of his firmest ideological declarations and turned it into a much more palatable and anodyne comment on totalitarianism. No matter how badly some people want Orwell to be a polished and uncontroversial product for mass consumption, he was still the man who wrote these words as he speculated about the possibility of violent revolution in England: “I dare say the London gutters will have to run with blood. All right, let them, if it is necessary.”

Even when Orwell wasn’t in a mood that had him impatiently looking forward to the day “when the red militias are billeted in the Ritz,” he was always honest about his political beliefs. On November 13, 1945, Katharine Stewart-Murray, the Duchess of Atholl, wrote to Orwell asking if he would speak on behalf of an anti-communist organization called the League for European Freedom. This was a month after the publication of Animal Farm — a time when Orwell was worried that the book would be misinterpreted as a broadside against socialism instead of a narrower attack on Stalinism.

Given this context, it isn’t surprising that Orwell declined the duchess’s offer: “Certainly what is said on your platforms is more truthful than the lying propaganda to be found in most of the press, but I cannot associate myself with an essentially Conservative body which claims to defend democracy in Europe but has nothing to say about British imperialism.” Even though Orwell was a staunch anti-communist, his essential political convictions remained immovable: “I belong to the Left and must work inside it, much as I hate Russian totalitarianism and its poisonous influence in this country.”

Orwell was a socialist until the end of his life. For many people, this complicates his legacy and detracts from his pristine image as the twentieth century’s foremost foe of totalitarianism — an image that has been appropriated again and again over the past 70 years.

[…]

But as Orwell was at pains to demonstrate (especially after the publication of Animal Farm), he would have firmly rejected the Right’s attempts to appropriate his legacy. While Orwell is rightly celebrated for his refusal to accept the dogmas of the Left when he was under tremendous pressure to do so, his independence of mind is only one of the reasons why he remains so relevant today. His ability to maintain that independence without sacrificing his most fundamental principles may be even more important.