Anthony Scaramucci is doing his very best impression of “Blake”, says Kevin Williamson:

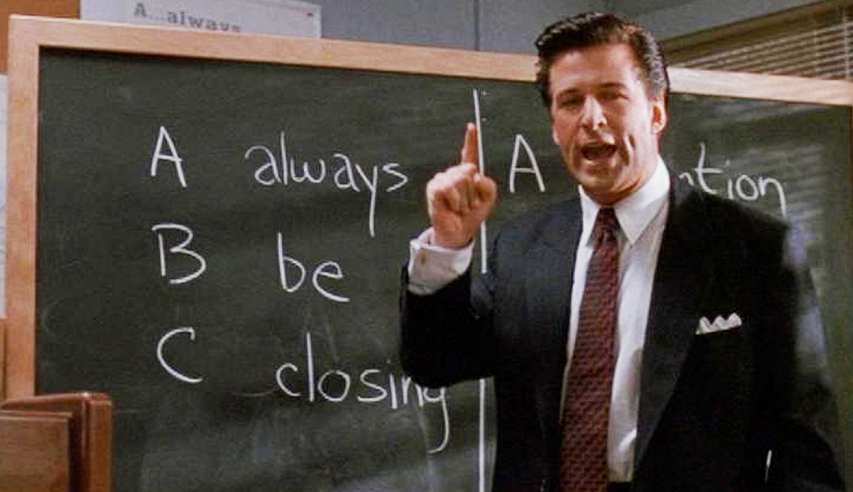

Glengarry Glen Ross is the Macbeth of real estate, full of great, blistering lines and soliloquies so liberally peppered with profanity that the original cast had nicknamed the show “Death of a F***ing Salesman.” But a few of those attending the New York revival left disappointed. For a certain type of young man, the star of Glengarry Glen Ross is a character called Blake, played in the film by Alec Baldwin. We know that his name is “Blake” only from the credits; asked his name by one of the other salesmen, he answers: “What’s my name? F*** you. That’s my name.” In the film, Blake sets things in motion by delivering a motivational speech and announcing a sales competition: “First prize is a Cadillac Eldorado. Second prize? A set of steak knives. Third prize is, you’re fired. Get the picture?” He berates the salesmen in terms both financial — “My watch cost more than your car!” — and sexual. Their problem, in Blake’s telling, isn’t that they’ve had a run of bad luck or bad sales leads — or that the real estate they’re trying to sell is crap — it is that they aren’t real men.

[…]

These guys don’t want to see Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross. What they want is to be Blake. They want to swagger, to curse, to insult, and to exercise power over men, exercising power over men being the classical means to the end of exercising power over women, which is of course what this, and nine-tenths of everything else in human affairs, is about. Blake is a specimen of that famous creature, the “alpha male,” and establishing and advertising one’s alpha creds is an obsession for some sexually unhappy contemporary men. There is a whole weird little ecosystem of websites (some of them very amusing) and pickup-artist manuals offering men tips on how to be more alpha, more dominant, more commanding, a literature that performs roughly the same function in the lives of these men that Cosmopolitan sex tips play in the lives of insecure women. Of course this advice ends up producing cartoonish, ridiculous behavior. If you’re wondering where Anthony Scaramucci learned to talk and behave like such a Scaramuccia, ask him how many times he’s seen Glengarry Glen Ross.

What’s notable about the advice offered to young men aspiring to be “alpha males” is that it is consistent with the classic salesmanship advice offered by the real-world versions of Blake in a hundred thousand business-inspiration books (Og Mandino’s The Greatest Salesman in the World is the classic of the genre) and self-help tomes, summarized in an old Alcoholics Anonymous slogan: “Fake it ’til you make it.” For the pick-up artists, the idea is that simply acting in social situations as though one were confident, successful, and naturally masterful is a pretty good substitute for being those things. Never mind the advice of Cicero (esse quam videri, be rather than seem) or Rush — just go around acting like Blake and people will treat you like Blake.

If that sounds preposterous, remind yourself who the president of the United States of America is.

Trump is the political version of a pickup artist, and Republicans — and America — went to bed with him convinced that he was something other than what he is. Trump inherited his fortune but describes himself as though he were a self-made man.

Update: I guess he came in third.