We’re edging ever close to the start of the Great War (no, I don’t know exactly how many more parts this will take … but we’re more than halfway there, I think). You can catch up on the earlier posts in this series here (now with hopefully helpful descriptions):

- Why it’s so difficult to answer the question “Who is to blame?”

- Looking back to 1814

- Bismarck, his life and works

- France isolated, Britain’s global responsibilities

- Austria, Austria-Hungary, and the Balkan quagmire

- The Anglo-German naval race, Jackie Fisher, and HMS Dreadnought

- War with Japan, revolution at home: Russia’s self-inflicted miseries

- The First Balkan War

- The Second Balkan War

The Balkans were the setting for two major wars among the regional powers (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Rumania, and the Ottoman Empire), but the wars had not spread to the rest of the continent. This run of good luck was not going to last much longer. We turn our attention to Britain, France, and Russia … as unlikely a set of allies as you’d find in the 1880s, now in the process of discovering a common threat in Europe.

Sir Edward Grey and Britain’s progress from “splendid isolation” to official ambivalence

The British government had spent most of the previous century staying out of continental disputes, only rarely becoming politically or militarily involved. Late in the nineteenth century, this began to change, and Britain started paying closer attention to what was happening on the continent and moving slowly toward re-engagement. While the British and the French had spent more time as enemies or as mutually distrustful neutrals, France was now looking across the Channel for much more than mere neutrality.

Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary 1905-1916

A key figure in negotiating Britain’s relationship with France was

Sir Edward Grey, who was Foreign Secretary from 1905 onwards (despite the minor difficulty of speaking no other languages and having no interest in visiting other countries). In retrospect, the degree of freedom he was allowed in this role is amazing, especially as he didn’t seem to think he was required to let the prime minister, the cabinet, or parliament know what he was doing until he’d arranged things largely to his own satisfaction.

Huw Strachan assigns most of the responsibility for the deepening relationship with France to Grey:

Sir Edward Grey had become foreign secretary on the formation of the Liberal government in December 1905, and remained in post until the end of 1916, so becoming the longest-serving holder of the post. Sir Edward brought diplomatic gravitas to his work in 1914. He had already convened the meeting of ambassadors that had contained and concluded the two Balkan wars of 1912-13. When the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on June 28 prompted a third Balkan crisis, it seemed unlikely to have any direct effect on British interests, but Sir Edward might still prove central to its resolution. If the “concert of Europe”, the international order created in 1814-15 after the Napoleonic wars, still had life, the foreign secretary was the person best placed to animate it.

Sir Edward’s qualifications for such responsibility were of recent coinage. Notoriously idle as a young man, he had been sent down from Oxford, but returned to get a third in jurisprudence. He entered politics as much through Whig inheritance as ambition. He spoke no foreign language and, when foreign secretary, never travelled abroad – or at least not until he had to accompany King George V to Paris in April 1914. He seemed happier as a country gentleman, enjoying his enthusiasms of fishing and ornithology. His first wife increasingly refused to come to London, remaining at Fallodon, the family seat in Northumberland. Their life together was chaste and childless, but not unaffectionate.

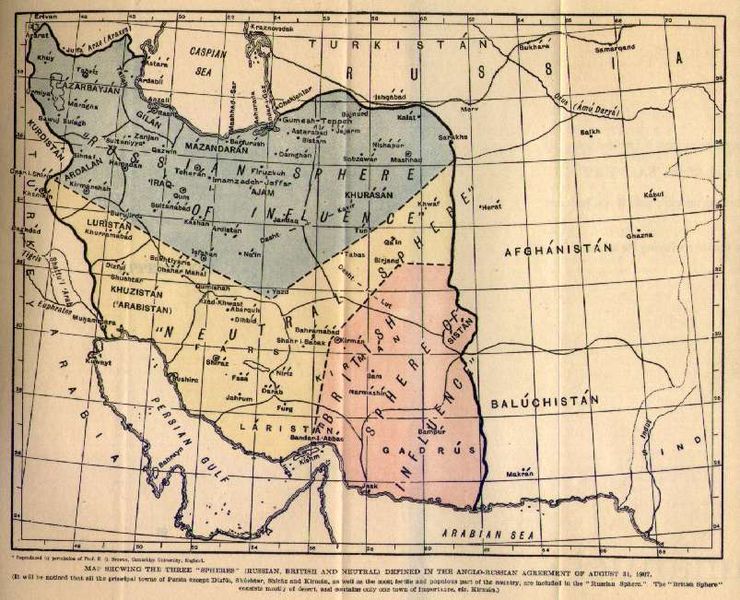

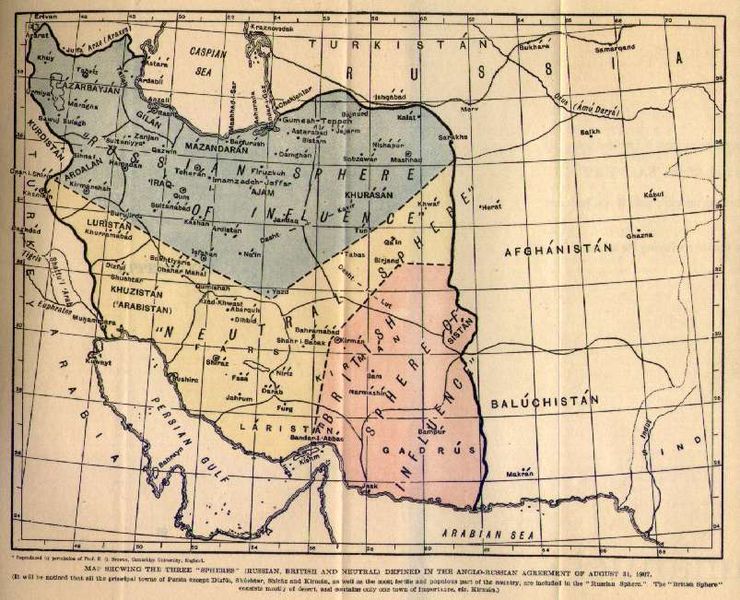

Soon after becoming Foreign Secretary, Grey was careful to assure Russian ambassador Count Alexander Benckendorff that he wanted a closer and less fraught relationship with St. Petersburg. Britain’s long-running dispute with the expanding Russian Empire in Asia stood in the way of any co-operation between the two great powers: the “Great Game” across central Asia had been in progress for nearly a century and neither side trusted the other. British concerns that any advance of Russian interests across that vast swathe of land were part of long term plans to destabilize the Indian frontier and eventually to absorb India. Whether these fears were realistic is beside the point: they had driven Raj policy in India despite the low chance of them turning into actual dangers. The disagreements were partially settled with the Anglo-Russian Convention in 1907, where both Russian and British regional interests were codified:

Formally signed by Count Alexander Izvolsky, Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire, and Sir Arthur Nicolson, the British Ambassador to Russia, the British-Russian Convention of 1907 stipulated the following:

- That Persia would be split into three zones: A Russian zone in the north, a British zone in the southeast, and a neutral “buffer” zone in the remaining land.

- That Britain may not seek concessions “beyond a line starting from Qasr-e Shirin, passing through Isfahan, Yezd (Yazd), Kakhk, and ending at a point on the Persian frontier at the intersection of the Russian and Afghan frontiers.”

- That Russia must follow the reverse of guideline number two.

- That Afghanistan was a British protectorate and for Russia to cease any communication with the Emir.

A separate treaty was drawn up to resolve disputes regarding Tibet. However, these terms eventually proved problematic, as they “drew attention to a whole range of minor issues that remained unsolved”.

Anglo-Russian spheres of influence in Persia, 1907 (via Wikipedia)

While the convention did not resolve every outstanding issue between the two imperial powers, it smoothed the path to further negotiations on European issues. One of the things the two had to consider was the expansion of German activity in Ottoman territory, especially the Baghdad Railway project, which threatened to extend German influence deep into the oil producing regions of Mesopotamia just as Britain was contemplating switching the Royal Navy from coal to oil. German engineers and financiers had already proven their worth to the Ottomans by building the Anatolian Railway in the 1890s, connecting Constantinople with Ankara and Konya.

Vernon Bogdanor’s recent History Today article explains Grey’s role in bringing Britain into the war alongside the French and Russians:

The growth of German power posed a challenge to an international system based on the Concert of Europe, developed at the Congress of Vienna following the defeat of Napoleon, whereby members could call a conference to resolve diplomatic issues, a system Britain, and particularly the Liberals in government in 1914, were committed to defend. Sir Edward Grey had been foreign secretary since 1905, a position he retained until 1916, the longest continuous tenure in modern times. He was a right-leaning Liberal who found himself subject to more criticism from his own backbenchers than from Conservative opponents. In his handling of foreign policy his critics alleged that Grey had abandoned the idea of the Concert of Europe and was worshipping what John Bright had called ‘the foul idol’ of the balance of power. They suggested that he was making Britain part of an alliance system, the Triple Entente, with France and Russia and that he was concealing his policies from Parliament, the public and even from Cabinet colleagues. By helping to divide Europe into two armed camps he was increasing the likelihood of war.

On his appointment in December 1905 Grey had indeed maintained the loose Anglo-French entente of 1904, which the Conservatives of the previous government had negotiated. He extended that policy by negotiating an entente with France’s ally, Russia, in 1907. In 1905 France was embroiled in a conflict with Germany over rival claims in Morocco. The French had essentially said to Lord Lansdowne, Grey’s Conservative predecessor: ‘Suppose this conflict leads to war – if you are to support us, let us consult together on naval matters to consider how your support can be made effective.’ The Conservatives had responded that, while they would discuss contingency plans, they could not make any commitments.

Grey continued the naval conversations and extended them to include military dialogue. He informed the prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman, and two senior ministers of these talks, but not the rest of the Cabinet. Nevertheless, Britain could not be committed to military action without the approval of both Cabinet and Parliament. In November 1912, at the insistence of the Cabinet, there was an exchange of letters between Grey and the French ambassador, Paul Cambon, making it explicit that Britain was under no commitment, except to consult, were France to be threatened. In 1914, furthermore, the French never suggested that Britain was under any sort of obligation to support them, only that it would be the honourable course of action.

Romancing the bear, romancing the lion: France breaks out of imposed isolation

As I discussed back in part four of this series, the French had been left diplomatically isolated in Europe by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, but that began to change as Kaiser Wilhelm II took the throne and started imposing his will on German foreign policy. French money opened opportunities for French diplomacy, to the long-term benefit of French security. The Franco-Russian alliance was signed in 1894, signifying the end of French encirclement (Bismarck’s policy) and the start of German encirclement (Kaiser Wilhelm’s nightmare).

Britannia and Marianne dancing together on a 1904 French postcard: a celebration of the signing of the Entente Cordiale. (via Wikipedia)

Anglo-French diplomatic efforts took longer to come to fruition, but by 1904, the

Entente Cordiale was more than just a pleasant diplomatic nicety, although it fell short of the full alliance France had hoped for. Among other things, the agreement traded French acceptance of Britain’s position in Egypt for British acceptance of France’s position in Morocco, along with some border adjustments in west Africa, fishing rights off the coast of Newfoundland, and other issues. The

Entente also allowed the two great powers to avoid being involved in the

Russo-Japanese War (discussed in

part seven), where they were each allied to the opposing powers. Each side saw the agreement in rather different terms, with the French believing it was the next best thing to an alliance, but as British foreign ministry staffer

Eyre Crowe expressed it: “The fundamental fact of course is that the

Entente is not an alliance. For purposes of ultimate emergencies it may be found to have no substance at all. For the

Entente is nothing more than a frame of mind, a view of general policy which is shared by the governments of two countries, but which may be, or become, so vague as to lose all content.”

French public opinion was still ambivalent at best about Britain — the PR and humanitarian disaster that was the Boer War had only just faded from the headlines, and there was still much resentment over the Fashoda incident — but the French government recognized the importance of gaining British support (and the British government was conscious of how low their international reputation had gone). Huw Strachan:

The previous Conservative government had in 1895 moved from “splendid isolation” to embrace the need to form alliances. But it was Sir Edward who narrowed these options by excluding the possibility of a deal with Germany. As a Liberal Imperialist, concerned by the evidence of British decline in the South African war, Sir Edward increasingly fixed Britain to France and then to Russia. The latter relationship may have looked frayed by 1914, but that with France was buttressed by military and naval talks. The result was not so much a balance of power in Europe as the isolation of Germany.

Moroccan crises and using the Kaiser as a bargaining chip

The First Moroccan Crisis of 1905-6 was a potential flashpoint between the Entente Cordiale and the German Empire. Germany was hoping to split the Entente or at least to gain territorial concessions in exchange for a resolution. Kaiser Wilhelm was on a cruise to the Mediterranean and had been intending to bypass Tangier, but the situation was manipulated by the Foreign Office in Berlin so that he eventually felt he had to put in an appearance. In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan describes the scene:

Although Bülow had repeatedly advised him to stick to polite formalities, Wilhelm got carried away in the excitement of the moment. To Kaid Maclean, the former British soldier who was the sultan’s trusted advisor, he said, “I do not acknowledge any agreement that has been come to. I come here as one Sovereign [sic] paying a visit to another perfectly independent sovereign. You can tell [the] Sultan this.” Bülow had also advised his master not to say anything at all to the French representative in Tangier, but Wilhelm was unable to resist reiterating to the Frenchman that Morocco was an independent country and that, furthermore, he expected France to recognize Germany’s legitimate interests there. “When the Minister tried to argue with me,” the Kaiser told Bülow, “I said ‘Good Morning’ and left him standing.” Wilhelm did not stay for the lavish banquet which the Moroccans had prepared for him but before he set off on his return ride to the shore, he found time to advise the sultan’s uncle that Morocco should make sure that its reforms were in accordance with the Koran. (The Kaiser, ever since his trip to the Middle East in 1898, had seen himself as the protector of all Muslims.) The Hamburg sailed on to Gibraltar, where one of its escort ships accidentally managed to ram a British cruiser.

Tension rose so high that both Germany and France were looking to their mobilization timetables (France cancelled all military leave and Germany started moving reserve units to the frontier) before the diplomats were able to agree to meet at the conference table rather than the battlefield. The Algeciras Conference lasted from January to April, 1906, and the French generally had the better of the negotiations (with support from Britain, Russia, Italy, Spain, and the United States) while the Germans found themselves supported only by the Austro-Hungarian delegation. France ended up making a few token concessions, but overall retained their position in Morocco.

The Agadir Crisis of 1911 was the second incident in Morocco, where Germany tried a little bit of literal gunboat diplomacy with the gunboat SMS Panther. The port of Agadir was closed to foreign trade, but the Panther (and later the light cruiser SMS Berlin) was sent to “protect German nationals” in southern Morocco from rebel forces. A minor problem turned out to be that there were no conveniently threatened Germans in the region. Margaret MacMillan:

The Foreign Ministry only got round to getting support for its claim that German interests and German subjects were in danger in the south of Morocco a couple of weeks before the Panther arrived off Agadir, when it asked a dozen German firms to sign a petition (which most of them did not bother to read) requesting German intervention. When the German Chancellor, Bethmann, produced this story in the Reichstag he was met with laughter. Nor were there any German nationals in Agadir itself. The local representative of the Warburg interests who was some seventy miles to the north started southwards on the evening of July 1. After a hard journey by horse along a rocky track, he arrived at Agadir on July 4 and waved his arms to no effect from the beach to attract the attention of the Panther and the Berlin. The sole representative of the Germans under threat in southern Morocco was finally spotted and picked up the next day.

France reacted to the German provocation, despite efforts by Sir Edward Grey to restrain them: eventually he recognized that “what the French contemplate doing is not wise, but we cannot under our agreement interfere”. German public opinion, on the other hand, was ecstatic:

After its setbacks earlier on in Morocco and in the race for colonies in general, with the fears of encirclement in Europe by the Entente powers, Germany was showing that it mattered. “The German dreamer awakes after sleeping for twenty years like the sleeping beauty,” said one newspaper.

[…]

In Germany, public opinion, which had been largely indifferent to colonies ten years earlier, now was seized with their importance. The German government, which was already under considerable pressure from those German businesses with interests in Morocco, felt that it had much to gain by taking a firm stand. […] The temptation for Germany’s new Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Holweg, and his colleagues to have a good international crisis to bring all Germans together in support of their government was considerable.

Eventually, after negotiations, France and Germany signed the Treaty of Fez, which granted France Germany’s recognition of her rights in Morocco in exchange for ceded French territory in French Equatorial Africa (which was annexed to the existing German colony in Togoland), including direct access to the Congo River. In addition, Spain was granted rights to a portion of northern Morocco which became Spanish Morocco.

Not part of the treaty terms, but of rather greater significance in the near future, France and Britain agreed to share responsibility for the naval defence of France: the Royal Navy took on the responsibility for defending the north coast of France, while the French navy redeployed almost all ships to the western Mediterranean with the explicit agreement to defend British interests in the region.

I’m finding each successive part of this blog series to be taking longer to put together, and not from a lack of material! I’m hoping to have the next installment posted sometime this weekend or early next week.