H/T to KA-CHING! for the image.

June 11, 2013

Remember the Canadian political scandals?

Andrew Coyne got the secret decoder ring from one of his readers:

A reader writes: “Is it not possible McGuinty went to Ford & asked him to pose for that videoto divert attention from the gas-plants?…1/3

— Andrew Coyne (@acoyne) June 11, 2013

… Then Ford realised the heat was on him so he gave Nigel $90,000 with which to repay Duffy…. 2/3

— Andrew Coyne (@acoyne) June 11, 2013

… Don’t try to tell me that having three inane scandals like this, all at the same time, is a coincidence.” I, uh, THINK he was kidding. 3/3

— Andrew Coyne (@acoyne) June 11, 2013

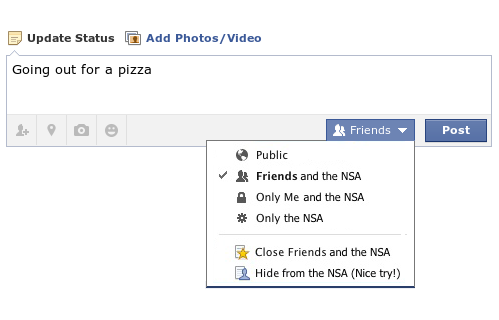

The elephant in the IT room – who can you trust?

At The Register, Trevor Pott explains why trust is the key part of your personal online security:

Virtually everything we work with on a day-to-day basis is built by someone else. Avoiding insanity requires trusting those who designed, developed and manufactured the instruments of our daily existence.

All these other industries we rely on have evolved codes of conduct, regulations, and ultimately laws to ensure minimum quality, reliability and trust. In this light, I find the modern technosphere’s complete disdain for obtaining and retaining trust baffling, arrogant and at times enraging.

Let’s use authentication systems as a fairly simple example. Passwords suck, we all know they suck, and yet the majority of us still try to use easy to remember (and thus easy to crack) passwords for virtually everything.

The use of password managers and two-factor authentication is on the rise, but we have once more run into a classic security versus usability issue with both technologies.

[. . .]

Trust as a design principle

The technosphere doesn’t think like this. Very few design their products around trust, or the lack thereof. We’ve become obsessed with how the technology works and what that technology can enable; technology is easy, people are hard. How the technology we create integrates into the larger reality of politics, law, emotion and the other people-centric elements, is often overlooked.

In some cases it is simply a matter of having a limited target audience; American firms designing for American users, for example. It is impossible for most to really understand the intricacies of trust issues in all their variegated permutations. It is human to be limited in our vision, and scope of understanding.

H/T to Bruce Schneier for the link.

“Who hired this goofball?”

Jim Geraghty talks about Edward Snowden and the NSA:

Everybody’s going to have an opinion on Edward Snowden, today the world’s most famous leaker.

In the coming days, you’re going to see a lot of people talking past each other, conflating two issues: one, did he do the right thing by disclosing all these details of the vast NSA system to gather data on Americans? And two, should he be prosecuted for it?

Of course, you can do the right thing and still break the law.

[. . .]

This may be a story with no heroes. A government system designed to protect the citizens starts collecting all kinds of information on people who have done nothing wrong; it gets exposed, in violation of oaths and laws, by a young man who doesn’t recognize the full ramifications of his actions. The same government that will insist he’s the villain will glide right past the question of how they came to trust a guy like him with our most sensitive secrets. Who within our national security apparatus made the epic mistake of looking him over — completing his background check and/or psychological evaluation — and concluding, “yup, looks like a nice kid?”

Watching the interview with Snowden, the first thing that is quite clear is that his mild-mannered demeanor inadequately masks a huge ego — one of the big motivations of spies. (Counterintelligence instructors have long offered the mnemonic MICE, for money, ideology, compromise, ego; others throw in nationalism and sex.)

Snowden feels he has an understanding of what’s going on well beyond most of his colleagues:

When you’re in positions of privileged access like a systems administrator for the sort of intelligence community agencies, you’re exposed to a lot more information on a broader scale then the average employee and because of that you see things that may be disturbing but over the course of a normal person’s career you’d only see one or two of these instances. When you see everything you see them on a more frequent basis and you recognize that some of these things are actually abuses.

What’s more, he feels that no one listens to his concerns or takes them seriously:

And when you talk to people about them in a place like this where this is the normal state of business people tend not to take them very seriously and move on from them. But over time that awareness of wrongdoing sort of builds up and you feel compelled to talk about. And the more you talk about the more you’re ignored. The more you’re told its not a problem until eventually you realize that these things need to be determined by the public and not by somebody who was simply hired by the government.”

My God, he must have been an insufferable co-worker.

‘Look, you guys just don’t understand, okay? You just can’t grasp the moral complexities of what I’m being asked to do here! Nobody here really gets what’s going on, or can see the big picture when you ask me to do something like that!’

‘Ed, I just asked if you could put a new bottle on the water cooler when you get a chance.’

Update: Politico put together a fact sheet on what we know about Edward Snowden. It’s best summed up by Iowahawk:

WTF? from HS dropout to Army washout to security guard to $200k/year cyber analyst to International Man of Mystery politico.com/story/2013/06/…

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) June 11, 2013

Federal government denies collecting electronic data on Canadians

Oh, well, if the government denies doing something I guess they pretty much have to be telling the truth, right? Unfortunately, the photo accompanying this Toronto Star article doesn’t show if Peter MacKay is crossing the fingers on his left hand:

The Conservative government flatly denies Canadian spy agencies are conducting any unauthorized electronic snooping operations.

After facing questions from the NDP Opposition about how far he has authorized Ottawa’s top secret eavesdropping spy agency to go, a terse Conservative Defence Minister Peter MacKay left the Commons, telling the Star: “We don’t target Canadians, okay.”

A former Liberal solicitor general says that doesn’t mean other allied spy agencies don’t collect information on Canadians and share it with the Canadian spying establishment.

Liberal MP Wayne Easter, who was minister responsible for the spy agency CSIS in 2002-03, told the Star that in the post-9/11 era a decade ago it was common for Canada’s allies to pass on information about Canadians that they were authorized to gather but Ottawa wasn’t.

The practice was, in effect, a back-door way for sensitive national security information to be shared, not with the government, but Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) and, if necessary, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).

CSEC is a new bit of alphabet soup in the public sphere … I’d never heard of the organization until yesterday. Tonda MacCharles explains what the agency is empowered to do:

The CSEC, an agency that is rarely in the public eye, has far-reaching national security powers to monitor and map electronic communication signals around the globe.

It is forbidden by law to target or direct its spying on Canadians regardless of their location anywhere in the world, or at any person in Canada regardless of their nationality.

The National Defence Act says CSE may, however, unintentionally intercept Canadians’ communications, but must protect their privacy in the use and retention of such “intercepted information.” The agency’s “use” of the information is also restricted to cases where it is “essential to international affairs, defence or security.”

CSEC’s job is to aid federal law enforcement and security agencies, including the military, in highly sensitive operations. It was a key component of Canadian operations in Afghanistan, for example.

As if a pregnant woman doesn’t have enough things to worry about…

…there’s an entire industry devoted to the cause of warning pregnant women about possible, potential, unknown dangers all around them:

The only other real option is to take the position held by Joan Wolf, author of the excellent study about contemporary risk thinking, Is Breast Best? Taking on the Breastfeeding Experts and the New High Stakes of Motherhood. Wolf has explored how, in the US, pregnant women are frequently told: everything is potentially risky; you have control over fetal development, but we do not know how; actions that you think are innocuous are probably harmful, but we cannot tell you which ones; things you do or do not do might be more problematic at certain times in pregnancy, but we do not know when; what you do or do not do can produce disastrous or moderately negative effects, but we cannot predict either one.

Wolf’s assessment is that the only rational response is not a call for more information of this kind; rather, it is to recognise that there is far too much of it already. While science can tell us important things, what we need to come to terms with is the inevitability of risk, the fact that people do risky things all day long (in that there are outcomes of actions over which we do not have total control), but this is just life. It is not a problem, and we do not need to be ‘informed’ or ‘empowered’ about it.

The other sort of argument made by the critics of the RCOG report was that instead of ‘raising awareness’ of the theoretical risks of everyday chemicals, more advice and information should be given to pregnant women about ‘real harm’. Hence, instead of just focusing on making it clear to the RCOG what they should do with their report, the critics have engaged in a sort of ‘my risk is bigger than your risk’ competition. In the discussion so far, the risks we apparently really understand and should be even more informed about have included all the old chestnuts: coffee, alcohol, cigarettes and stress.

Indeed, an interesting ‘my risk is bigger than your risk’ theme is developing when it comes to ‘stress’. Here, the entirely legitimate point that it is not reasonable to worry people and cause anxiety for no reason has morphed into a claim about the apparently overwhelming evidence that ‘stress’ endangers the developing fetus. In reality, as the US sociologist Betsy Armstrong has explained, the ‘science’ supporting the idea that stress in pregnancy is a problem is far more contentious than such objections assume. The wider public discourse about this issue demands robust criticism not endorsement because of its scaremongering qualities. In any case, given that a pregnant woman can no more avoid ‘stress’ in her life than a she can a pre-prepared ham sandwich, it is worth asking quite where this line of argument takes us.