More generally, though, do we have any historical evidence of groups whose alcohol consumption was documented with any confidence, to see how they fared?

Actually, we do, at least as a floor: we know the quantity of the Royal Navy’s spirit ration, which until 1823 was based on half a pint of rum (284 millilitres in foreign) per man per day. We also know its minimum strength, since it was tested by trying to ignite gunpowder soaked in it: it had to be over 57% alcohol by volume (“proof strength”) to pass. That’s sixteen units of alcohol – not per week, but per day – or north of a hundred units a week, just for the issued ration before sailors bought any extra from the purser. (No wonder Jack Tar was jolly back in those days!)

But clearly, we would expect a body of men consuming such suicidally destructive quantities of booze to be physical wrecks, raddled by cirrhosis and disease? As Dr James Lind (he of the discovery that citrus fruits were a sovereign remedy for scurvy) put it,

It is an observation, I think, worthy of record that fourteen thousand persons, pent up in ships, should continue, for six or seven months, to enjoy a better state of health upon the watery element, than it can well be imagined so great a number of people would enjoy, on the most healthful spot of ground in the world.

(For context, around this point the Navy won the battle of Quiberon Bay, with twenty ships – who had less than one man sick per ship).

The ration was halved in 1823, and again in 1850, but for a hundred and twenty years until Black Tot Day in 1970, the Navy still issued nearly thirty units of alcohol a week to everyone on the lower deck (junior rates got theirs diluted, seniors got neat rum). Either folk were hardier back then, or Britannia managed to rule the waves and keep her sailors reasonably healthy despite being a pack of hopelessly addicted alcoholics.

Jason Lynch, “How Much Is ‘Too Much’?”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-05-08.

July 29, 2020

QotD: Grog in the Royal Navy

June 9, 2020

Gunnery, Guns & Ammo in the Age of Sail (1650 -1815)

Military History Visualized

Published 4 Nov 2016» HOW YOU CAN SUPPORT MILITARY HISTORY VISUALIZED «

(A) You can support my channel on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/join/mhv(B) Alternatively, you can also buy “Spoils of War” (merchandise) in my online shop: https://www.redbubble.com/people/mhvi…

» SOCIAL MEDIA LINKS «

twitter: https://twitter.com/MilHiVisualized

tumblr: http://militaryhistoryvisualized.tumb…» SOURCES & LINKS «

Gardiner, Robert: “Guns and Gunnery”, in: Gardiner, Robert; Lavery, Brian: The Line of Battle – The Sailing Warship 1650-1840, p. 146-161

Tracy, Nicholas: “Naval Tactics in the Age of Sail”, in: Stilwell, Alexander: The Trafalgar Companion.

» CREDITS & SPECIAL THX «

Song: Ethan Meixsell – “Demilitarized Zone”The Counter-Design is heavily inspired by Black ICE Mod for the game Hearts of Iron 3 by Paradox Interactive

https://forum.paradoxplaza.com/forum/…

April 4, 2020

Eighteenth century health improvements through “ventilators”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes relates how a mistaken belief still led to a significant improvement in health:

One of the most worrying diseases of the mid-eighteenth century was typhus. We now know that it is spread by lice or fleas, but at the time, like so many other diseases, it was thought to be caused by noxious air — “malaria”, for example, literally means “bad air”. This was not a silly theory. It was based on empirical observation, which perhaps explains why the belief in such noxious miasmas persisted for so long — well into the late nineteenth century, if not the early twentieth, before finally being ousted by germ theory. Our ancestors were not stupid, no matter how strange their beliefs might appear in hindsight. (Also take alchemy, or the belief that some animals spontaneously generated.)

The Central Tower of the Palace of Westminster is actually a disguised ventilator.

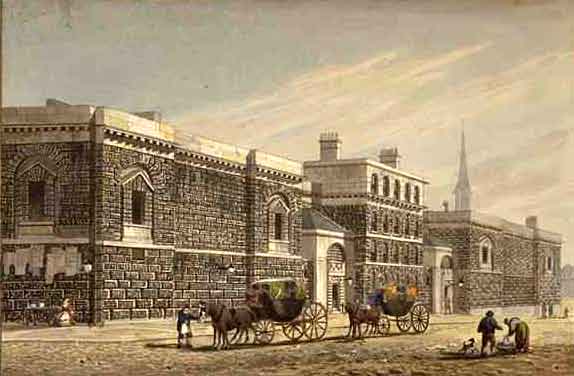

Photo by Cary Bass via Wikimedia Commons.Typhus fit the miasma theory especially well because it frequently appeared in confined spaces, like ships’ holds, prisons, mines, workhouses, and hospitals. The disease was thus often called “gaol fever”, or “hospital fever”. And there was the fact that at least one of the solutions designed to combat miasmas, the ventilator, actually seemed to work. This ventilator was not the kind that is in such high demand right now, used to help feed oxygen into patients’ lungs, but instead a machine used to get the air flowing in and out of confined spaces — like a 1740s air-conditioning unit.

At first glance, removing the stale air from a space shouldn’t do anything against typhus. But mortality declined drastically in the prisons and ships to which the ventilator was introduced. It halved the number of deaths per year in Newgate prison, where the bellows-like machinery was powered by a windmill, and the inmates of the Savoy prison fared even better. On ships, too, mortality declined among mariners, passengers, soldiers, and especially among the group that suffered most from long voyages across the eighteenth-century Atlantic: slaves.

But it’s not clear exactly why. After all, the ventilator did not kill the typhus-ridden lice or fleas. I have a few theories as to what must have been going on. Perhaps, by improving the supply of oxygen to confined spaces, people’s bodies were simply better served to deal with all manner of diseases. Surgeons aboard slave ships sometimes noted that, without proper ventilation, many slaves would simply die in the night of suffocation. Or perhaps the ventilator’s effectiveness had something to do with its drying effect. The machine was used to prevent grain stores from becoming humid, thus staving off damp-loving weevils. The ventilators might thus have staved off typhus through a similar means: although I’m not so certain about body lice, humid conditions are preferred by fleas. Regardless of the real reasons, the ventilators worked, and even when they did not reduce mortality, they made confined spaces more bearable for those who had to endure them. Ship captains reported that they did not even have to force their sailors to pump the ventilator’s bellows, because they liked the cool air so much. Ventilators were soon installed in the House of Commons, and in many of London’s theatres.

From the Wikipedia entry on architectural ventilation:

The development of forced ventilation was spurred by the common belief in the late 18th and early 19th century in the miasma theory of disease, where stagnant ‘airs’ were thought to spread illness. An early method of ventilation was the use of a ventilating fire near an air vent which would forcibly cause the air in the building to circulate. English engineer John Theophilus Desaguliers provided an early example of this, when he installed ventilating fires in the air tubes on the roof of the House of Commons. Starting with the Covent Garden Theatre, gas burning chandeliers on the ceiling were often specially designed to perform a ventilating role.

Mechanical systems

A more sophisticated system involving the use of mechanical equipment to circulate the air was developed in the mid 19th century. A basic system of bellows was put in place to ventilate Newgate Prison and outlying buildings, by the engineer Stephen Hales in the mid-1700s. The problem with these early devices was that they required constant human labour to operate. David Boswell Reid was called to testify before a Parliamentary committee on proposed architectural designs for the new House of Commons, after the old one burned down in a fire in 1834. In January 1840 Reid was appointed by the committee for the House of Lords dealing with the construction of the replacement for the Houses of Parliament. The post was in the capacity of ventilation engineer, in effect; and with its creation there began a long series of quarrels between Reid and Charles Barry, the architect.Reid advocated the installation of a very advanced ventilation system in the new House. His design had air being drawn into an underground chamber, where it would undergo either heating or cooling. It would then ascend into the chamber through thousands of small holes drilled into the floor, and would be extracted through the ceiling by a special ventilation fire within a great stack.

Reid’s reputation was made by his work in Westminster.

February 20, 2020

So that’s why John Cabot got hired!

Anton Howes explains something that I’d wondered about in the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter:

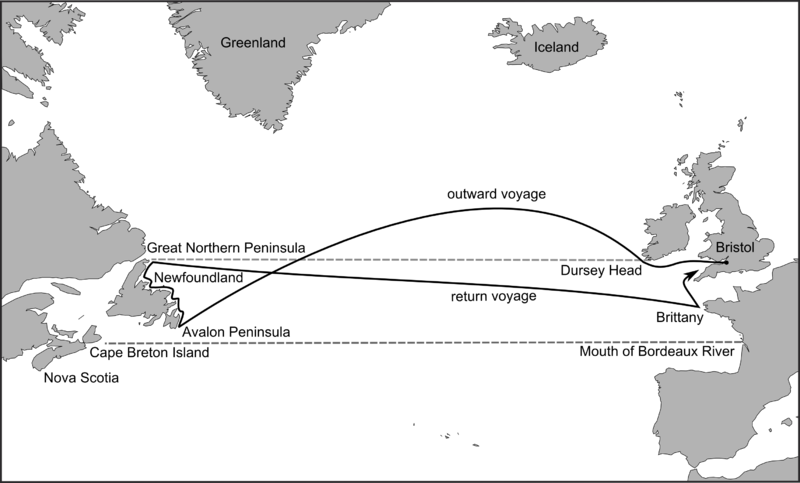

Route of John Cabot’s 1497 voyage on the Matthew of Bristol posited by Jones and Condon: Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, Nov. 2016), fig. 8, p. 43.

Wikimedia Commons.

… in 1550 the English were still struggling with latitude. Their inability to find it, unlike their Spanish and Portuguese rivals, was one of the main things holding them back from voyages of exploration.

The replica of John Cabot’s ship Matthew in Bristol harbour, adjacent to the SS Great Britain.

Photo by Chris McKenna via Wikimedia Commons.The traditional method of navigation for English pilots was to simply learn the age-old routes. They were trained through repetition and accrued experience, learning to recognise particular landmarks and using a lead and line – just a thin rope weighted with some lead – to determine their location from the depth of the water. Cover the lead with something sticky, and you might bring up some sediment from the sea floor to double-check: a pilot would learn the kinds of sand and pebbles from to expect from different areas. And when they travelled out to sea, away from the coastline, they used a basic system of dead reckoning, taking their compass bearings from a known location, estimating their speed, and keeping in a particular direction for long enough. Or at least hoping to. They might keep track of their progress on a wooden traverse table, inserting pegs to indicate how far they had sailed, but it was ultimately a matter of rough estimation. Should they make any mistake — in terms of their speed, heading, or point of departure — they might easily get lost. But it was still a matter of trying to follow an already-known route. And English mariners of the 1550s did not even know that many routes.

For a voyage of exploration, by contrast, landmarks and sediment from the sea floor would be seen for the first time rather than recalled. By definition, there was no route to follow. So to launch their own voyages of discovery, the English needed to learn a new skill. They needed to look to the heavens.

Celestial navigation — measuring the altitude of heavenly bodies and then using geometry to determine one’s latitude on the earth’s surface — was by the 1550s already hundreds of years old. It had primarily been used to cross the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East — seas of sand, in which there might also be no landmarks from which to take bearings — and to navigate the Indian Ocean. Thus, while pilots in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean stuck to dead reckoning and soundings, Islamic navigators had for centuries used quadrants and astrolabes to take their bearings at sea. By the mid-fifteenth century, these instruments and techniques had found their way to Europe, where they were put to use especially by Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian explorers, along with additional instruments such as the cross-staff.

[…]

So for decades, English explorations relied on foreigners who either knew the routes that the English pilots didn’t, or who at least possessed the skill of mathematical, celestial navigation. The Italian explorer John Cabot (Zuan Chabotto), when he sailed to Newfoundland from Bristol in the late 1490s, was able to take latitude readings (he may even have been familiar with the older Islamic navigational practices, as he claimed to have visited Mecca). When Cabot died, the English expeditions that set out from Bristol in 1501-3 relied on Portuguese pilots from the mid-Atlantic islands of the Azores. And John Cabot’s son, Sebastian Cabot, who was involved in a few English expeditions, was so expert in mathematical navigation that he was eventually appointed pilot major for the entire Spanish Empire, making him responsible for the training and licensing of all its pilots — a position he held for three decades. When he led a voyage of exploration on behalf of Spain in 1526-30, a few English merchants became investors so that they could justify sending with him an English mariner, Roger Barlow, to secretly learn the Spanish routes across the Atlantic and have immediate knowledge if an onward route to Asia was discovered (as it turned out, South America got in the way).

May 31, 2019

History Buffs: Master and Commander

History Buffs

Published on 18 Sep 2016History Buffs is back! To thank you all for your patience while I’ve been away on holiday, I’m starting off with Master and Commander!

SUPPORT HISTORY BUFFS ON PATREON

https://www.patreon.com/HistoryBuffs● Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/HistoryBuffsNH

_________________________________________________________________________

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World is a 2003 American epic historical drama film written, produced and directed by Peter Weir. The film stars Russell Crowe as Captain Jack Aubrey and Paul Bettany as Dr. Stephen Maturin. The film, which cost $150 million to make, was a co-production of 20th Century Fox, Miramax Films, Universal Pictures, and Samuel Goldwyn Films, and released on November 14, 2003 to critical acclaim. The film’s plot and characters are adapted from three novels in author Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey–Maturin series, which includes 20 completed novels of Jack Aubrey’s naval career.

At the 76th Academy Awards, the film was nominated for 10 Oscars, including Best Picture. It won in two categories, Best Cinematography and Best Sound Editing and lost in all other categories to The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

February 22, 2019

Germany’s armed forces – from world class to laughing stock

Germany’s military has fallen on very hard times, and there’s so much wrong that it will be very difficult to fix even with all the goodwill in the world:

The German Navy training ship Gorch Fock (launched in 1958) under full sail (less the spanker topsail) in Kiel Fjord near the Laboe Naval Memorial in July 2006.

Photo by Felix Koenig via Wikimedia Commons.

Most Germans’ eyes glaze over at the mention of the Bundeswehr’s perpetual troubles, but an affair surrounding the Gorch Fock, the navy’s three-masted naval training ship, has caught their attention.

Launched in 1958 to school a new generation of West German naval recruits, the imposing 81-meter ship, which takes its name from a popular seafaring German author’s pseudonym, is more than just a training vessel; to many, the Gorch Fock — whose likeness was etched onto some Deutsche Mark bills — is a symbol of Germany’s postwar revival.

The ship’s iconic status is one reason why few objected when the Bundeswehr announced in 2015 that it needed a major overhaul. Until, that is, the price tag exploded from an initial projection of €10 million to €135 million, according to the latest estimate.

Bundeswehr officials claimed the depth of the ship’s troubles only became clear when it was in dry dock, but few are buying such explanations. “When the repairs cost more than a new ship, something is obviously amiss,” Bartels, the Bundeswehr’s parliamentary overseer, said in an interview.

The Gorch Fock “is a symptom of the Bundeswehr’s broader problems,” Bartels said. “Everything takes too long and costs too much money. It’s as if time and money were endless resources, and in the end no one takes responsibility.”

Almost overnight, the ship has gone from pride and joy to running gag. Last week, German weekly Der Spiegel pictured the Gorch Fock on its cover under the headline, “Ship of Fools.”

It’s an apt metaphor for Germany’s body politic as well. Given Germany’s size and economic might, Berlin’s attention to security is surprisingly shallow; citizens and politicians alike often seem oblivious to the challenges the country faces. Though Germany faces growing security threats from both Russia and China, one wouldn’t know it hanging around the German capital.

Much of the media now portrays the U.S. as a security threat on par with Russia. Public attitudes have moved in a similar direction. Security discussions are driven by a handful of like-minded think tank analysts who seem to spend most their time on Twitter, fretting about whether Trump will pull the plug on NATO.

More Germans believe China is a better partner for their country than the U.S., according to a survey published last week by Atlantik Brücke, a Berlin-based transatlantic lobbying group. About 80 percent of those surveyed consider U.S.-German relations to be “negative” or “very negative.”

H/T to Instapundit for the link.

February 12, 2013

The Bluenose II in court

The descendents of the designer of the original Bluenose are in court to demand the “copyright, and the moral rights in the copyright work” of the vessel which probably should be called the “Bluenose III“:

The Bluenose sank to the bottom in 1946; the replica Bluenose II was built in 1963, and then rebuilt in recent years and launched from the Lunenburg wharf this past September amid much fanfare and, as the province’s accountants could tell you, serious cost overruns.

No matter. This was a gala affair. Only Joan Roué and her father, Lawrence J. Roué — grandson of William J. Roué — were not among the smiling guests and proceeded to file suit against the province, the boat designers and boat builders in October, alleging that despite “the province owning the vessel … Joan and Lawrence Roué allege that they are respectively entitled to the copyright, and the moral rights in the copyright work” associated with the latest incarnation of the famous schooner.

To which the province responded — and I am paraphrasing here — “are you people kidding me?” while contending in court filings that William J. Roué’s storied original design perhaps wasn’t all that original to begin with, and, even if it were a singular masterpiece, that he had already been paid for it decades ago.

I posted about the “new” Bluenose II last year, explaining why I think they should have incremented the number in the vessel’s official name:

Wooden sailing ships are subject to far more wear and tear than modern vessels: they’re like the old tale of the farmer’s axe (even though everything’s been replaced over time, it’s still the same axe). This means that heritage sailing ships need lots of careful maintenance throughout their lives, and major re-builds at long intervals. In the case of Nova Scotia’s iconic Bluenose II, however, it’s sometimes more than a “rebuild” […] So, just to sum up: she’s being built to a different design (even though outward appearance is much the same), using different materials. In what way can you call her the same ship? The point made in the article, that the masts and sails were some of the “originals” being re-used is odd: those are among the parts that need replacing more often. And the mahogany and walnut saved from the last boat are almost certainly decorative elements, not structural ones.

December 19, 2012

ARA Libertad finally free to sail home from Ghana

If you’ve been following the debt-related travails of the Argentine navy’s flagship, you’ll recall that the ship was impounded on a visit to Ghana back in October. The BBC is now reporting that the ship has been released, and Argentinian sailors will be able to take the frigate home after a UN court decision:

The Libertad set sail from Ghana’s main port of Tema after a United Nations court last week ordered its release.

Argentina sent almost 100 navy personnel to man the three-masted training ship.

It was impounded after a financial fund said it was owed money by Argentina’s government as a result of a debt default a decade ago.

[. . .]

In November, sailors on board the Libertad reportedly pulled guns on Ghanaian officials when they tried to board the vessel to move it to another berth.

The lengthy diplomatic row began when the ship was prevented from leaving Ghana on 2 October, after a local court ruled in favour of financial fund NML Capital. The fund is a subsidiary of US hedge fund Elliot Capital Management which is one of Argentina’s former creditors.

October 25, 2012

Follow-up – Argentine flagship’s crew to fly home after three week delay

I originally found this story at the beginning of the month, and after all this time, the bulk of the Argentinian crew finally fly home. BBC News has the update:

Almost 300 sailors left on an Air France plane chartered by the Argentine government.

A skeleton crew is staying on board the three-masted Libertad to maintain it.

The tall ship was prevented from leaving Ghana after a local court ruled in favour of a US fund.

The fund, NML Capital, argued it was owed $370m (£231m) by Argentina’s government as a result of its debt default a decade ago.

[. . .]

An earlier plan for the sailors to fly back on an Argentine plane was scrapped because of fears that the aircraft might itself be impounded as part of the debt dispute.

On Tuesday, Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner condemned the Libertad’s seizure and made it clear there would be no negotiations with creditors.

October 7, 2012

Flagship of Argentinian Navy seized for unpaid government debt in Ghana

If I were you, I’d avoid investing in any Argentinian business (or businesses which have significant operations in Argentina), as the government is doing everything it can to prevent the flight of capital. Some of the debt holders are getting quite creative about finding ways to put pressure on Argentina to pay its debts:

If pirating didn’t work out, Capt. Jack Sparrow would perhaps have made a savvy hedge fund manager.

A New York hedge fund boss is being dubbed a real pirate of the Caribbean after seizing the flagship of the Argentinian navy in an attempt to settle some of the country’s huge debt.

Billionaire Paul Singer took control of the tall ship the A.R.A. Libertad with a court order in Ghana this week.

The triple-mast frigate, which stopped in the African country as it trained naval cadets, is valued at $10 million and is the ceremonial flagship of the Argentine fleet.

September 13, 2012

Cutty Sark now housed in “worst new building in Britain”

Andrew Gilligan tells the sad story of the Cutty Sark‘s new “home”:

The architectural trade journal, Building Design, has announced that the historic tea clipper is the 2012 winner of the Carbuncle Cup, the wooden spoon for the dregs of British architecture.

The architects, Grimshaw, have taken something delicate and beautiful and surrounded it with a building that looks like a 1980s bus station. Clumsy and ineptly detailed, their new glass greenhouse around the Cutty Sark totally ruins her thrilling lines, obscures much of her exquisite gilding and cynically forces anyone who actually wants to see her to pay their £12 and go inside. The sight of people pressing their faces forlornly against the smoked glass to try to see something of the ship is one of the sadder in London.

Grimshaw have also punched a shopping centre-style glass lift up through the middle of the ship — and put two more lifts in a new square building, the size of a small block of flats, next to and towering over the ship herself. They’ve plonked a glass pod on the open main deck for a staircase (the old housing was wood, but that’s so nineteenth-century). They’ve installed lights on the masts which make it look like a Christmas tree. Above all, of course, they’ve hoicked the ship up on girders, dangling above the dry dock to create an “unparalleled corporate entertaining space” underneath — an act of vandalism that prompted the resignation of the chief engineer, who said it would place the vessel under unacceptable strain and end in its destruction.

Cutty Sark was severely damaged in a drydock fire in May 2007.

July 6, 2012

If it’s being “rebuilt” to a different design, with different materials, it’s not the same Bluenose

Wooden sailing ships are subject to far more wear and tear than modern vessels: they’re like the old tale of the farmer’s axe (even though everything’s been replaced over time, it’s still the same axe). This means that heritage sailing ships need lots of careful maintenance throughout their lives, and major re-builds at long intervals. In the case of Nova Scotia’s iconic Bluenose II, however, it’s sometimes more than a “rebuild”:

She is a celebrity, immortalized on the back of our dime and presently parked beneath a big white tent in the Lunenburg Shipyard, awaiting finishing touches and the order to set sail.

Built in 1963, Bluenose II was effectively scrapped in the fall of 2010. A small percentage of the old boat, including the sails and masts and some of the mahogany and walnut from the hull, were saved for use in the rebuild. The bow-to-stern reconstruction had the legend at points looking more like a whale skeleton beached on the Lunenburg wharf, with her ribs exposed for all to see.

Some purists, including Ms. Roué, a great-granddaughter of William J. Roué — the naval architect responsible for designing the original Bluenose, which launched in 1921 and achieved lasting fame by hauling in massive catches on the Grand Banks and beating American schooners in ocean races — view the “restoration” tag as a semantic stretch.

They see it as a sham concealing the fact the boat being built and expected to launch this summer under the Bluenose II banner was not built according to Mr. Roué’s original designs. It is not the Bluenose II but a new boat altogether.

You could make the case that this is merely a look-alike, rather than a replica. In fact you’d pretty much have to say that:

The original Bluenose was made from Nova Scotia oak, while its second incarnation blended local and South American oaks.

The latest edition consists of laminated angelique, a bulletproof teak from South America. Meanwhile the engine bed, stern frame, floors and fasteners holding the whole shebang together are steel, where once they were wood.

Any boat, especially a boat named Bluenose, is more than the materials it is made of or the sum of its designs. It is a piece of living history and its identity derives from the stories attached to it and in the recollections of those that sailed aboard her, some accounted for, others lost at sea.

So, just to sum up: she’s being built to a different design (even though outward appearance is much the same), using different materials. In what way can you call her the same ship? The point made in the article, that the masts and sails were some of the “originals” being re-used is odd: those are among the parts that need replacing more often. And the mahogany and walnut saved from the last boat are almost certainly decorative elements, not structural ones.

July 10, 2009

Sunken 1812 vessel may be HMS Wolfe

An interesting article in the Ottawa Citizen about a recently discovered wreck near Kingston, which may be the remains of HMS Wolfe:

A team of divers is set to plunge into Lake Ontario near Kingston, Ont., next week in a bid to confirm the discovery of a legendary Canadian-built ship from the War of 1812, the HMS Wolfe.

In collaboration with marine archeologists from Parks Canada, the divers plan to take detailed measurements, drawings and photographs of a sunken wooden sailing vessel that appears to match the size and last known location of the famous 32-metre sloop: the flagship of British naval commander James Yeo and star of a dramatic 1813 battle west of Toronto that helped thwart the U.S. invasion of Canada.

The suspected discovery comes just three years before the 200th anniversary of the war, adding urgency to the efforts to identify a possible new showcase relic for bi-national commemoration activities.

(Cross-posted to the old blog: http://bolditalic.com/quotulatiousness_archive/005570.html.)