Over the last week, I’ve posted entries on what I think are the deep origins of the First World War (part one, part two, part three, part four, part five). And yes, to be honest, I didn’t think it would take quite this many entries to begin to explain how the world catastrophe of August 1914 came about — putting together this series of blog posts has been educational for me, and I hope it’s been at least of interest to you. The previous post examined the history of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, in some detail (yes, it matters). Today, we finally clear the Victorian era altogether and begin to look at the last decade-or-so before the outbreak of the war.

The Anglo-German naval race

Even after the creation of the German Reich in 1871, Germany was not seen (by the British government) to be a major threat to British interests: Germany had no significant presence beyond Europe to worry the Colonial Office, and instead was seen as a potentially useful balancing factor in the European theatre. That all changed with the accession of Kaiser Wilhelm II as explained by Christopher Clark in The Sleepwalkers:

The 1890s were […] a period of deepening German isolation. A commitment from Britain remained elusive and the Franco-Russian Alliance seemed to narrow considerably the room for movement on the continent. Yet Germany’s statesmen were extraordinarily slow to see the scale of the problem, mainly because they believed that the continuing tension between the world empires was in itself a guarantee that these would never combine against Germany. Far from countering their isolation through a policy of rapprochement, German policy-makers raised the quest for self-reliance to the status of a guiding principle. The most consequential manifestation of this development was the decision to build a large navy.

In the mid-1890s, after a long period of stagnation and relative decline, naval construction and strategy came to occupy a central place in German security and foreign policy. Public opinion played a role here — in Germany, as in Britain, big ships were the fetish of the quality press and its educated middle-class readers. The immensely fashionable “navalism” of the American writer Alfred Thayer Mahan also played a part. Mahan foretold in The Influence of Sea Power upon History: 1660–1783 (1890) a struggle for global power that would be decided by vast fleets of heavy battleships and cruisers. Kaiser Wilhelm II, who supported the naval programme, was a keen nautical hobbyist and an avid reader of Mahan; in the sketchbooks of the young Wilhelm we find many battleships — lovingly pencilled floating fortresses bristling with enormous guns. But the international dimension was also crucial: it was above all the sequence of peripheral clashes with Britain that triggered the decision to acquire a more formidable naval weapon. After the Transvaal episode, the Kaiser became obsessed with the need for ships, to the point where he began to see virtually every international crisis as a lesson in the primacy of naval power.

The Royal Navy (RN) had been Britain’s most obvious sign of global dominance, and Britain’s fleets had gone through many technological changes over the century since Waterloo. What had been for centuries a slow, steady process of gradual improvement and incremental change suddenly became the white-hot centre of rapid, even revolutionary, change:

At the same time that you need to add armour to protect the ship, you also need to mount heavier, larger guns. Between placing your order with the shipyard for a new ship, the metallurgical wizards may have (and frequently did) come up with bigger, better guns that could defeat the armour on your not-yet-launched ship. Oh, and you now needed to revise the design of the ship to carry the newer, heavier guns, too.

The ship designers were in a race with the gun designers to see who could defeat the latest design by the other group. It’s no wonder that ships could become obsolete between ordering and coming into service: sometimes, they could become obsolete before launch.

The weapons themselves were undergoing change at a relatively unprecedented rate. As late as the mid-1870′s, a good case could be made for muzzle-loading cannon being mounted on warships: until the gas seal of the breech-loader could be made safe, muzzle-loaders had an advantage of not killing their own crews at distressingly high frequency. Once that technological handicap had been overcome, then the argument came down to the best way to mount the weapons: turrets or barbettes.

The RN’s international prestige invited envious imitators (like Wilhelm) and challengers (the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy), but the RN was the supreme naval power against which all other nations measured themselves. In 1889, parliament passed the Naval Defence Act, which specified that the Royal Navy would be maintained at the “two-power standard”: that the RN’s fleet of capital ships would be at least equal to the number of battleships maintained by the next two largest navies (at that time, the French and Russian navies). The increased spending allowed ten battleships plus cruisers and torpedo boats to be added to the fleet … but the French and Russian navies added twelve battleships between them over the same period of time. “Another British expansion, known as the Spencer Programme, followed in 1894 aimed to match foreign naval growth at a cost of over £31 million. Instead of deterring the naval expansion of foreign powers, Britain’s Naval Defence Act contributed to a naval arms race. Other powers including Germany and the United States bolstered their navies in the following years as Britain continued to increase its own naval expenditures.”

In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan describes the implicit power of the RN in peacetime:

In August 1902 another great naval review took place at Spithead in the sheltered waters between Britain’s great south coast port of Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight, this time to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII. Because he had suddenly come down with appendicitis earlier in the summer, the coronation itself and all festivities surrounding it had been postponed. As a result, most of the ships from foreign navies (except those of Britain’s new ally Japan) as well as those from the overseas squadrons of the British navy had been obliged to leave. The resulting smaller review was, nevertheless, The Times said proudly, a potent display of Britain’s naval might. The ships displayed at Spithead were all in active service and all from the fleets already in place to guard Britain’s home waters. “The display may be less magnificent than the wonderful manifestation of our sea-power witnessed in the same waters five years ago. But it will demonstrate no less plainly what that power is, to those who remember that we have a larger number of ships in commission on foreign stations now than we had then, and that we have not moved a single ship from Reserve.” “Some of our rivals,” The Times warned, “have worked with feverish activity in the interval, and they are steadily increasing their efforts. They should know that Britain remained vigilant and on guard, and prepared to spend whatever funds were necessary to maintain its sovereignty of the seas.”

Admiral Fisher’s new broom

Admiral Sir John “Jackie” Fisher (via Wikipedia)

In 1904,

Admiral Sir John “Jackie” Fisher was appointed as First Sea Lord (the professional head of the RN, reporting to the First Lord of the Admiralty, a cabinet minister). Fisher was a full-steam-ahead reformer, with vast notions of modernizing and reforming the navy. He was brilliant, argumentative, abrasive, tactless, and aggressive but could also be charming and persuasive. “When addressing someone he could become carried away with the point he was seeking to make, and on one occasion, the king asked him to stop shaking his fist in his face.” (Fortunately for Fisher, the king was a personal friend, so this did not hinder his career.)

Margaret MacMillan describes him in The War That Ended Peace:

Jacky Fisher, as he was always known, shoots through the history of the British navy and of the prewar years like a runaway Catharine wheel, showering sparks in all directions and making some onlookers scatter in alarm and others gasp with admiration. He shook the British navy from top to bottom in the years before the Great War, bombarding his civilian superiors with demands until they usually gave way and steamrollering over his opponents in the navy. He spoke his mind freely in his own inimitable language. His enemies were “skunks”, “pimps”, “fossils”, or “frightened rabbits”. Fisher was tough, dogged and largely immune to criticism, not surprising perhaps in someone from a relatively modest background who had made his own way in the navy since he was a boy. He was also supremely self-confident. Edward VII once complained that Fisher did not look at different aspects of an issue. “Why should I waste my time,” the admiral replied, “looking at all sides when I know my side is the right side?”

Fisher had been a maverick throughout his career (which makes it even more amazing that he eventually did rise to become First Sea Lord), as his actions when he took command of the Mediterranean Fleet clearly illustrate:

A programme of realistic exercises was adopted including simulated French raids, defensive manoeuvres, night attacks and blockades, all carried out at maximum speed. He introduced a gold cup for the ship which performed best at gunnery, and insisted upon shooting at greater range and from battle formations. He found that he too was learning some of the complications and difficulties of controlling a large fleet in complex situations, and immensely enjoyed it.

Notes from his lectures indicate that, at the start of his time in the Mediterranean, useful working ranges for heavy guns without telescopic sights were considered to be only 2000 yards, or 3000-4000 yards with such sights, whereas by the end of his time discussion centred on how to shoot effectively at 5000 yards. This was driven by the increasing range of the torpedo, which had now risen to 3000-4000 yards, necessitating ships fighting effectively at greater ranges. At this time he advocated relatively small main armaments on capital ships (some had 15 inch or greater), because the improved technical design of the relatively small (10 inch) modern guns allowed a much greater firing rate and greater overall weight of broadside. The potentially much greater ranges of large guns was not an issue, because no one knew how to aim them effectively at such ranges. He argued that “the design of fighting ships must follow the mode of fighting instead of fighting being subsidiary to and dependent on the design of ships.” As regards how officers needed to behave, he commented, “‘Think and act for yourself’ is the motto for the future, not ‘Let us wait for orders’.”

Lord Hankey, then a marine serving under Fisher, later commented, “It is difficult for anyone who had not lived under the previous regime to realize what a change Fisher brought about in the Mediterranean fleet. … Before his arrival, the topics and arguments of the officers messes … were mainly confined to such matters as the cleaning of paint and brasswork. … These were forgotten and replaced by incessant controversies on tactics, strategy, gunnery, torpedo warfare, blockade, etc. It was a veritable renaissance and affected every officer in the navy.” Charles Beresford, later to become a severe critic of Fisher, gave up a plan to return to Britain and enter parliament, because he had “learnt more in the last week than in the last forty years”.

One of his first changes was to sell nearly one hundred elderly ships and move dozens of less capable vessels from the active list to the reserve fleet, to free up the crews (and the maintenance budget) for more modern vessels, describing the ships as “too weak to fight and too slow to run away”, and “a miser’s hoard of useless junk”. Between his reforms as Third Sea Lord (where he had championed the development of the modern destroyer and vastly increased the efficiency and productivity of the shipyards) and his new role as First Sea Lord, Fisher was able to get more done even on a budget that dropped nearly 10% in the year of his appointment than his predecessor had managed.

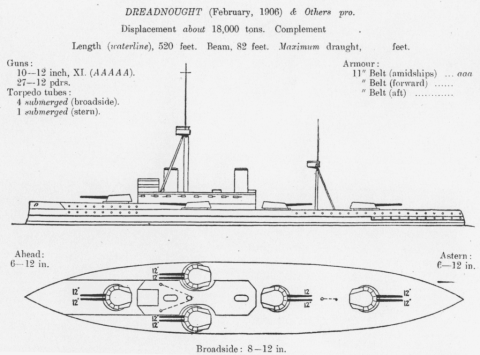

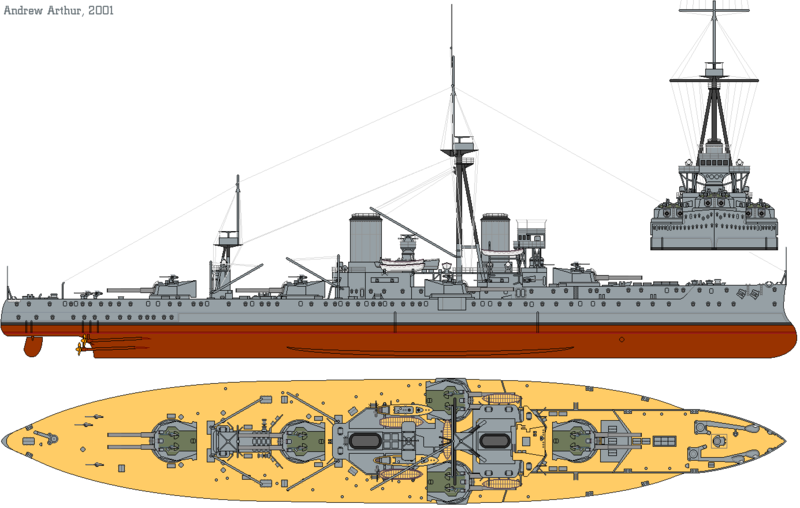

HMS Dreadnought and the naval revolution

Fisher was not a naval designer, but he knew how to push new ideas to the front and get them adopted. The one thing that most people remember him for is the revolutionary battleship HMS Dreadnought, the first all big gun, fast steam turbine powered battleship, and when she went into commission, she signified the obsolescence of every other capital ship in every navy from that moment onwards.

HMS Dreadnought underway, circa 1906-07

Dreadnought was the platonic ideal of a battleship: she was faster than any other capital ship in any other navy, her guns were at least the equivalent in range, rate of fire, and throw of shot, and her armour was sufficient to allow her to take punishment from opposing ships and still deal out damage herself. She was the first British ship to be equipped with electrical controls allowing the entire main armament to be fired from a central location. Thanks to Fisher’s earlier efforts with the shipyards, Dreadnought took just a year to build — far faster than any other battleship had been built.

The “entirely crazy Dreadnought policy of Sir J. Fisher and His Majesty”

The Kaiser was not happy with the new British battleship, as it had been German policy since his accession to build up the German navy to at least provide a tool for pressuring Britain (if not for actually confronting the Royal Navy in battle). Now his entire naval plan had been upset by the Dreadnought revolution. Margaret MacMillan:

As far as the Kaiser and [Admiral] Tirpitz were concerned the responsibility for taking the naval race to a new level rested with what Wilhelm called the “entirely crazy Dreadnought policy of Sir J. Fisher and His Majesty”. The Germans were prone to see Edward VII as bent on a policy of encircling Germany. The British had made a mistake in building dreadnoughts and heavy cruisers, in Tirpitz’s view, and they were angry about it: “This annoyance will increase as they see that we follow them immediately.” […] Who could tell what the British might do? Did their history not show them to by hypocritical, devious and ruthless? Fears of a “Kopenhagen”, a sudden British attack just like the one in 1807 when the British navy had bombarded Copenhagen and seized the Danish fleet, were never far from the thoughts of the German leadership once the naval race had started.

German fears of British attack increased almost in lockstep with British fears of German attack (William Le Queux had his equivalents among the German press and popular novelists). The thought had actually occurred to Fisher himself, who outlined a possible coup de main against the German fleet. The king responded “My God, Fisher, you must be mad!” and the suggestion was ignored, thankfully.

The popular worries about an attack from Britain fed the support for the German Navy laws, which funded dreadnought and battlecruiser building programs. In direct proportion, the increased German support for their naval expansion worked to the advantage of British politicians who wanted to build more dreadnoughts of their own. And, in fairness, Britain risked far more by allowing an enlarged German navy than Germany risked by stopping their building program … but in either case, the fear of popular unrest kept the shipyards humming anyway. As Churchill later wrote, “The Admiralty had demanded six ships; the economists offered four; and we finally compromised on eight.”

There we go, finally getting within striking distance of the triggering events of the First World War … and I’m still not sure how many more posts it will take to get us there! More to come this week.