In any case, the demand that actors should play only those parts that are somehow consonant with what we now call their “lived experience” is self-evidently absurd. If taken seriously, Richard III would have to be played by a member of the Royal Family (Prince Andrew, perhaps?), for only such a person could know or imagine what it was like to be a royal person and covet the crown. Taken to its logical conclusion, or its reductio ad absurdum, the argument would mean that the only person an actor could play was him- or herself.

Of course, a happy medium exists, though we are increasingly unable to find it. We should not expect Ophelia to be played by a 90-year-old crone. We should add difficulties in the way of an audience’s “willing suspension of disbelief”, as Coleridge put it, by casting a tall man as short or a short man as tall.

The whole silly controversy reveals to what absurdities we have sunk, thanks to identity politics and a willful misunderstanding, for the sake of personal or group advantage, of what wrongful discrimination is. Storms in teacups can be revealing.

Theodore Dalrymple, “My Kingdom for Some Crutches”, New English Review, 2024-02-06.

May 13, 2024

QotD: Of course, they could try just … acting

November 22, 2023

“[T]he Tudors were indeed pretty awful, and that the writers who lived under this dynasty did serve as propagandists”

I quite like a lot of what Ed West covers at Wrong Side of History, but I’m not convinced by his summary of the character of King Richard III nor do I believe him guilty of murdering his nephews, the famed “Princes in the Tower”:

As Robert Tombs put it in The English and their History, no other country but England turned its national history into a popular drama before the age of cinema. This was largely thanks to William Shakespeare’s series of plays, eight histories charting the country’s dynastic conflict from 1399 to 1485, starting with the overthrow of the paranoid Richard II and climaxing with the War of the Roses.

This second part of the Henriad covered a 30-year period with an absurdly high body count – three kings died violently, seven royal princes were killed in battle, and five more executed or murdered; 31 peers or their heirs also fell in the field, and 20 others were put to death.

And in this epic national story, the role of the greatest villain is reserved for the last of the Plantagenets, Richard III, the hunchbacked child-killer whose defeat at Bosworth in 1485 ended the conflict (sort of).

Yet despite this, no monarch in English history retains such a fan base, a devoted band of followers who continue to proclaim his innocence, despite all the evidence to the contrary — the Ricardians.

One of the most furious responses I ever provoked as a writer was a piece I wrote for the Catholic Herald calling Richard III fans “medieval 9/11 truthers”. This led to a couple of blogposts and several emails, and even an angry phone call from a historian who said I had maligned the monarch.

This was in the lead up to Richard III’s reburial in Leicester Cathedral, two and a half years after the former king’s skeleton was found in a car park in the city, in part thanks to the work of historian Philippa Langley. It was a huge event for Ricardians, many of whom managed to get seats in the service, broadcast on Channel 4.

Apparently Philippa Langly’s latest project — which is what I assume raised Ed’s ire again — is a new book and Channel 4 documentary in which she makes the case for the Princes’ survival after Richard’s reign although (not having read the book) I’d be wary of accepting that they each attempted to re-take the throne in the guises of Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck.

The Ricardian movement dates back to Sir George Buck’s revisionist The History of King Richard the Third, written in the early 17th century. Buck had been an envoy for Elizabeth I but did not publish his work in his lifetime, the book only seeing the light of day a few decades later.

Certainly, Richard had his fans. Jane Austen wrote in her The History of England that “The Character of this Prince has been in general very severely treated by Historians, but as he was a York, I am rather inclined to suppose him a very respectable Man”.

But the movement really began in the early 20th century with the Fellowship of the White Boar, named after the king’s emblem, now the Richard III Society.

It received a huge boost with Josephine Tey’s bestselling 1951 novel The Daughter of Time in which a modern detective manages to prove Richard innocence. Paul Murray Kendall’s Richard the Third, published four years later, was probably the most influential non-fiction account to take a sympathetic view, although there are numerous others.

One reason for Richard’s bizarre popularity is that the Tudors were indeed pretty awful, and that the writers who lived under this dynasty did serve as propagandists.

Writers tend to serve the interests of the ruling class. In the years following Richard III’s death John Rous said of the previous king that “Richard spent two whole years in his mother’s womb and came out with a full set of teeth and hair streaming to his shoulders”. Rous called him “monster and tyrant, born under a hostile star and perishing like Antichrist”.

However, when Richard was alive the same John Rous was writing glowing stuff about him, reporting that “at Woodstock … Richard graciously eased the sore hearts of the inhabitants” by giving back common lands that had been taken by his brother and the king, when offered money, said he would rather have their hearts.

Certainly, there was propaganda. As well as the death of Clarence, William Shakespeare — under the patronage of Henry Tudor’s granddaughter — also implicated Richard in the killing the Duke of Somerset at St. Albans, when he was a two-year-old. The playwright has him telling his father: “Heart, be wrathful still: Priests pray for enemies, but princes kill”. So it’s understandable why historians might not believe everything the Bard wrote about him.

I must admit to a bias here, as I wrote back in 2011:

In the interests of full disclosure, I should point out that I portrayed the Earl of Northumberland in the 1983 re-enactment of the coronation of Richard III (at the Cathedral Church of St. James in Toronto) on local TV, and I portrayed the Earl of Lincoln in the (non-televised) version on the actual anniversary date. You could say I’m biased in favour of the revisionist view of the character of good King Richard.

May 19, 2023

They made a MOVIE about the discovery of Richard III’s remains!!!

Vlogging Through History

Published 16 Sept 2022Here’s a fantastic hour-long breakdown of the entire search and discovery process – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dsTyG…

(more…)

July 13, 2020

“The Richard of Richard III is often regarded as a caricature, a cardboard-cutout villain rather like the Sweeney Todd of Victorian melodrama”

Theodore Dalrymple discusses two Shakespeare characters, the protagonists of Richard II and Richard III:

This was long thought to be the only portrait of William Shakespeare that had any claim to have been painted from life, until another possible life portrait, the Cobbe portrait, was revealed in 2009. The portrait is known as the “Chandos portrait” after a previous owner, James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos. It was the first portrait to be acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 1856. The artist may be by a painter called John Taylor who was an important member of the Painter-Stainers’ Company.

National Portrait Gallery image via Wikimedia Commons.

… if we cannot know Shakespeare’s positive thoughts about any major question, as Nutall puts it, we can at least surmise some of the things that he did not believe. No one, I think, could imagine that Shakespeare romanticized the common man or was impressed by a crowd’s capacity for deep reflection. If there is one thing that he was not, it is a utopian.

Apart from the absence of direct evidence, one reason that it is so difficult to know what Shakespeare thought is that he seemed uniquely able to imagine himself into the minds of an almost infinite number of characters, so that he actually became them. He was, in a sense, like an actor who has played so many parts that he no longer has a personality of his own. A chameleon has many colors, but no color. What is perhaps even more remarkable is that, by some verbal alchemy, Shakespeare turns us into a pale version of himself. Through the great speeches or dialogues, we, too, enter a character’s world, or even become that character in our minds. I know of no other writer able to do this so often and across so wide a spectrum of humanity.

Included in this spectrum are the two King Richards, the Second and the Third. Shakespeare wrote the two plays in reverse historical order, about four years apart. The usurpation of Richard II’s throne in 1399 by Henry Bolingbroke, Henry IV, led to political instability and civil war in England that lasted until the death of Richard III in battle in 1485. Because everyone loves an unmitigated villain, Richard III is said to be the most frequently performed of all Shakespeare’s plays, but its historical verisimilitude is much disputed. It is clearly an apologia for the Tudor dynasty, for if Richard III were not the absolute villain he is portrayed as having been (and such is the power of Shakespeare’s play that everyone’s image of the king, except for those specially interested, derives from it), then Henry VII, whose dynastic claims to the throne were meager, to say the least, was not legitimately king — in which case neither was Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth’s father, nor, therefore, was Queen Elizabeth legitimately queen: a dangerous proposition at the time Shakespeare wrote. So reminiscent of sycophantic Soviet historical apologetics does a Soviet emigré friend of mine find the play that he detests it. In 1924, a surgeon in Liverpool, Samuel Saxon Barton, founded what became the Richard III Society, which now has several thousand members globally, to rescue the reputation of the king from the Bard’s calumnies.

If Richard III were merely a propaganda play on behalf of the Tudors, however, it would hardly have held its place in the repertoire. It does so because it tackles the perennially fascinating, and vitally important, question of evil in the most dramatic manner imaginable; its historical inaccuracy does not matter. Richard III may not have been the dark figure Shakespeare portrays, but who would dare to say that no such figure could ever have existed?

The two plays offer a contrast between different political pathologies: that of ambitious malignity and that of arrogant entitlement, both with disastrous results, and neither completely unknown in our time. They share one rather surprising thing in common, however: before reaching the throne, both usurpers — Richard III, when still Duke of Gloucester; and Henry IV, when still Duke of Hereford — felt obliged to solicit the good opinion of the common people. This is perhaps surprising, in view of the extremely hierarchical nature of society in both the age depicted in the plays and the age in which they were written, and suggests a nascent populism, if not real democracy. However powerful the king or nobility, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, early in the reign of Richard II (as much a revolt of merchants as of peasants), must have alerted them to the need to keep the populace at least minimally satisfied.

Update: Fixed broken link and mis-placed image.

July 26, 2017

February 8, 2017

British History’s Biggest Fibs with Lucy Worsley Episode 1 War of the Roses [HD]

Published on 27 Jan 2017

Lucy debunks the foundation myth of one of our favourite royal dynasties, the Tudors. According to the history books, after 30 years of bloody battles between the white-rosed Yorkists and the red-rosed Lancastrians, Henry Tudor rid us of civil war and the evil king Richard III. But Lucy reveals how the Tudors invented the story of the ‘Wars of the Roses’ after they came to power to justify their rule. She shows how Henry and his historians fabricated the scale of the conflict, forged Richard’s monstrous persona and even conjured up the image of competing roses. When our greatest storyteller William Shakespeare got in on the act and added his own spin, Tudor fiction was cemented as historical fact. Taking the story right up to date, with the discovery of Richard III’s bones in a Leicester car park, Lucy discovers how 15th-century fibs remain as compelling as they were over 500 years ago. As one colleague tells Lucy: ‘Never believe an historian!

March 22, 2015

A different interpretation of the Battle of Bosworth

In the Telegraph, Chris Skidmore looks at the end of the Battle of Bosworth in the light of the injuries suffered by King Richard:

Richard III’s body was discovered among the dead strewn across the battlefield, “despoiled to the skin” and “all besprung with mire and filth”. It was hard to believe that this naked and bloodied corpse had once belonged to a king. Still Richard III’s body had one final journey to make. After “many other insults were heaped upon it”, one chronicler reported how “not very humanely, a halter was thrown round the neck, and it was carried to Leicester”. With “nought being left about him, so much as would cover his privy member”, the last Plantagenet king was trussed up on the back of a horse, “as a hog or another vile beast” to be brought into the town “for all men to wonder upon, and there lastly irreverently buried”.

The new king — Henry Tudor, now crowned Henry VII — had good reason to put Richard’s body on display. Few could believe that Richard was dead, much less that a Welsh rebel who had landed on the tip of Wales two weeks earlier, leading an army of a few thousand men, mostly French mercenaries, had defeated a reigning king. Only hours earlier, Richard had led his army of 15,000 men, the largest army ever assembled “on one side” that England had ever witnessed, into battle against a rebel army barely one third its size. Bosworth, quite simply, was a battle that Richard should never have lost. Why did it go so badly wrong?

Treason, without a doubt:

With the collapse of his vanguard, Richard would have expected that his rear-guard, led by Henry Percy, the earl of Northumberland, to provide re-inforcements. Instead the earl did nothing. One chronicler was insistent that ‘in the place where the earl of Northumberland was posted, with a large company of reasonably good men, no engagement could be discerned, and no battle blows given or received”. Northumberland, Jean Molinet observed, should have “charged the French” but instead “did nothing except to flee, both he and his company, and to abandon his King Richard” since he had already agreed a secret pact with Henry Tudor.

Northumberland was a northern lord whose own power had diminished over the past decade as a result of Richard’s rise to power. He had nothing to lose and everything to gain from abandoning his king. Other reports from the battlefield suggest that Northumberland may have not only left Richard to his fate, but actively turned against him and “left his position and passed in front of the king’s vanguard”, at which point, “turning his back on Earl Henry, he began to fight fiercely against the king’s van, and so did all the others who had plighted their faith to Earl Henry”. If this were the case, it would explain why Richard had been heard “shouting again and again that he was betrayed, and crying ‘Treason! Treason! Treason!’”

Not just treason, but double treason:

The “first onslaught” of Richard’s attack saw some men surrounding Tudor been killed instantly, including Henry’s standard bearer, William Brandon, standing just feet away. It seemed that victory was now in Richard’s grasp. Not only had some of Henry’s men chose to flee, his standard had been ‘thrown to the ground’. Henry’s own men were ‘now wholly distrustful of victory’. Richard’s frenzied energy seemed to be turning the tables, as the king “began to fight with much vigour, putting heart into those that remained loyal, so that by his sole effort he upheld the battle for a long time”. It was at this point that Sir William Stanley, having sat out the battle on its fringes, sent orders for his forces, numbering perhaps 3,000 men, to crash into the side of Richard’s detachment, taking Tudor’s side. Richard stood no chance. He was swept off his horse and into a marsh, where he was killed, “pierced with numerous deadly wounds” one chronicler wrote, “while fighting, and not in the act of flight”.

Update: Maclean’s has a long article up on the Canadian connections to Richard III.

January 25, 2015

September 18, 2014

Forensic report on the death of Richard III

BBC News has the details:

Sarah Hainsworth, study author and professor of materials engineering, said: “Richard’s injuries represent a sustained attack or an attack by several assailants with weapons from the later medieval period.

“Wounds to the skull suggest he was not wearing a helmet, and the absence of defensive wounds on his arms and hands indicate he was still armoured at the time of his death.”

Guy Rutty, from the East Midlands pathology unit, said the two fatal injuries to the skull were likely to have been caused by a sword, a staff weapon such as halberd or bill, or the tip of an edged weapon.

He said: “Richard’s head injuries are consistent with some near-contemporary accounts of the battle, which suggest Richard abandoned his horse after it became stuck in a mire and was killed while fighting his enemies.”

June 16, 2014

The tomb for Richard III

BBC News has images of the tomb designed for the re-burial of Richard III at Leicester Cathedral:

The design of the tomb King Richard III will be reburied in at Leicester Cathedral, has been unveiled.

The wooden coffin will be made by Michael Ibsen, a descendent of Richard III, while the tomb will be made of Swaledale fossil stone, quarried in North Yorkshire.

The total cost of reburial is £2.5m and work will start in the summer.

The Very Reverend David Monteith, Dean of Leicester, said the design “evokes memory and is deeply respectful”.

Judges ruled his remains, found under a Leicester car park in 2012, would be reinterred in Leicester, following a judicial review involving distant relatives of the king who wanted him buried in York.

A new visitor centre is set to open in July, which will tell the story of the king’s life, his brutal death in Battle in 1485 and rediscovery of his remains.

May 30, 2014

“Historical” High Court judgment that ignores history

Last week, the High Court decided that the remains of King Richard III will be re-buried in Leicester, not in York. As you might expect, that leaves a lot of people unhappy.

When Richard III was hacked to death in rural Leicestershire in 1485, the royal House of York fell, bringing an end to the Plantagenet line that had lasted for 16 kings and 331 years. Many people see his death as the end of the English middle ages.

Despite this country’s ancient legal system, the courts do not often get to deal with real history, although they make many historic decisions. Yet the ruling of the High Court last Friday truly made history, as three judges decided that Richard III should be buried at the scene of his violent defeat, and not in York.

One side is always unhappy after a court hearing. And in this case those who sponsored York Minster may have more to be sore about than most.

The High Court acknowledged the case has “unprecedented” and “unique and exceptional features,” but nevertheless went on to give a rather bland ruling supporting Chris Grayling’s decision to leave the matter of reburial in the hands of the University of Leicester team running the excavation. In doing so, the court treated the hearing as a straightforward matter of public law, and affirmed that the government had been under no duty to consult widely before handing the responsibility over to the University of Leicester.

[…]

History and legacy mattered to medieval monarchs. Their actions, even the less obvious ones, were intended to make statements to reinforce their dynastic power. York Minster is an ancient foundation, home to the throne of the second most senior churchman in England. There has been an Archbishop of York since at least the seventh century. For Richard, a scion of the house of York, the Minster was an obvious place to fuse the sacred and secular, binding royal and church power together in one of England’s most venerable religious buildings. By contrast, Leicester Cathedral, although a lovely building with a long tradition of worship on the site, was a parish church until 1927 when it became the city’s cathedral. Although there was a church there in Richard’s day, it does not have the dynastic associations that Richard was clearly building with York.

And there’s always the religious aspect to consider (which would have been true regardless of the High Court’s decision):

And finally, the question of the liturgy is also set to run. As the old joke goes: Q. What is the difference between a terrorist and a liturgist? A. You can reason with a terrorist. Leicester cathedral has diligently teamed up with an expert medieval musicologist, who has painstakingly uncovered and proposed the finer details of prayers and music appropriate to a 15th-century reburial. However, strong feelings which go beyond the musical arrangements have been expressed in many quarters, including in an online petition, and by Dr John Ashdown-Hill, the historian who led the excavations. These views reflect a conviction that Richard should have a Roman Catholic ceremony that respects the faith in which he grew up and died, and which is honest to what his wishes would have been. Leicester Cathedral will certainly have their hands full trying to reconcile Richard’s pre-Reformation religious beliefs with the Church of England ceremonies they are permitted to conduct.

February 14, 2014

Shakespeare’s Richard III

John Lennard is a fan of William Shakespeare and it shows in this blog post:

The Imploding I

Shakespeare’s Richard III is the principal source of a figure still current in drama and cinema — the witty devil we love to hate. Fusing the role of the (aspiring) King with that of the Vice (the tempter in morality plays, who as a player of tricks and user of disguises was always more theatrically aware than his innocent victims), Shakespeare produced a role that from his first, mesmerising soliloquy, beginning the play, commands both amused and horrified attention. As witty as he is ruthless, and as witting about himself as about others, Richard dominates the stage whenever he is on it, and all his tricks come off marvellously — until they don’t.

I’ve just transcribed the Folio text of the play it calls The Tragedy of Richard the Third : with the Landing of Earle Richmond, and the Battell at Bosworth Field […] and I was struck by how potently verse and punctuation record Richard’s force and his final implosion. Here’s that famous opening soliloquy:

Enter Richard Duke of Gloster, solus.

Now is the Winter of our Discontent,

Made glorious Summer by this Son of Yorke :

And all the clouds that lowr’d vpon our house

In the deepe bosome of the Ocean buried.

Now are our browes bound with Victorious Wreathes,

Our bruised armes hung vp for Monuments ;

Our sterne Alarums chang’d to merry Meetings ;

Our dreadfull Marches, to delightfull Measures.

Grim-visag’d Warre, hath smooth’d his wrinkled Front :

And now, in stead of mounting Barbed Steeds,

To fright the Soules of fearfull Aduersaries,

He capers nimbly in a Ladies Chamber,

To the lasciuious pleasing of a Lute.

But I, that am not shap’d for sportiue trickes,

Nor made to court an amorous Looking-glasse :

I, that am Rudely stampt, and want loues Maiesty,

To strut before a wonton ambling Nymph :

I, that am curtail’d of this faire Proportion,

Cheated of Feature by dissembling Nature,

Deform’d, vn-finish’d, sent before my time

Into this breathing World, scarse halfe made vp,

And that so lamely and vnfashionable,

That dogges barke at me, as I halt by them.

Why I (in this weake piping time of Peace)

Haue no delight to passe away the time,

Vnlesse to see my Shadow in the Sunne,

And descant on mine owne Deformity.

And therefore, since I cannot proue a Louer,

To entertaine these faire well spoken dayes,

I am determined to proue a Villaine,

And hate the idle pleasures of these dayes.

Plots haue I laide, Inductions dangerous,

By drunken Prophesies, Libels, and Dreames,

To set my Brother Clarence and the King

In deadly hate, the one against the other :

And if King Edward be as true and iust,

As I am Subtle, False, and Treacherous,

The day should Clarence closely be mew’d vp :

About a Prophesie, which sayes that G,

Of Edwards heyres the murtherer shall be.

Diue thoughts downe to my soule, here Clarence comes.Everything here serves to present Richard’s complete control, and it’s an excellent example of the Ciceronian style and balance that characterises much of Shakespeare’s most fluent and speakable verse. For all its dynamism the language is exceptionally balanced and structured, bracing opposites within lines (“Our sterne Alarums chang’d to merry Meetings”, “That dogges barke at me, as I halt by them”) ; within couplets (“Now is the Winter of our Discontent, / Made glorious Summer by this Son of Yorke”, “Vnlesse to see my Shadow in the Sunne, / And descant on mine owne Deformity”) ; and within the quatrains that dominate the grammatical structure (“And now, in stead of mounting Barbed Steeds, / To fright the Soules of fearfull Aduersaries, / He capers nimbly in a Ladies Chamber, / To the lasciuious pleasing of a Lute”). The whole flows as trippingly as commandingly from the tongue, as generations of great actors have found, and the language is so strong and clear that it can bear very different styles of presentation. The two best Richards I’ve had the luck to see on stage, Anthony Sher and Ian McKellen, could not have tackled the role more differently — Sher was seriously hunched and scuttling on calipers that became weapons, feelers, probes at will ; McKellen was a restrained and clipped army officer whose only visible deformity was a hand kept always in his pocket — but both could draw equal strength and suasion from the magnificent verse Shakespeare provided.

February 6, 2013

English accents, circa 1483

I’m afraid the coverage of the discovery and identification of the remains of Richard III have done bad things to the newspapers. We’re starting to see articles like this posted:

King Richard III was ‘a brummie’

King Richard III would have spoken with a Birmingham accent, according to a language expert.Dr Philip Shaw, from the University of Leicester’s School of English, used two letters penned by the last king of the Plantagenet line more than 500 years ago to try to piece together what the monarch would have sounded like.

He studied the king’s use of grammar and spelling in postscripts on the letters.

The university has now released a recording of Dr Shaw mimicking King Richard reading extracts from those letters.

Despite being the patriarch of the House of York, the king’s accent “could probably associate more or less with the West Midlands” than from Yorkshire or the North of England, said Dr Shaw.

Wow. This must have been a long, painstaking effort to pin down the linguistic “tics” that help indicate a person’s natural speaking habits. What were the key elements that indicated Good King Richard was a “Brummie”?

“… there is also at least one spelling he employs that may suggest a West Midlands accent.”

That’s it? One spelling variation that “suggests” he would pronounce that one word in a similar manner to the modern Birmingham style? Gah!

February 5, 2013

What did King Richard III look like?

A facial reconstruction based on the skull of Richard III:

A facial reconstruction based on the skull of Richard III has revealed how the English king may have looked.

The king’s skeleton was found under a car park in Leicester during an archaeological dig.

The reconstructed face has a slightly arched nose and prominent chin, similar to features shown in portraits of Richard III painted after his death.

Historian and author John Ashdown-Hill said seeing it was “almost like being face to face with a real person”.

The development comes after archaeologists from the University of Leicester confirmed the skeleton found last year was the 15th Century king’s, with DNA from the bones having matched that of descendants of the monarch’s family.

I was unable to find an image of the reconstruction that is okay to use, but you can see various pictures on Google Image Search.

February 4, 2013

University of Leicester confirms that the remains are those of King Richard III

BBC News rounds up the details:

A skeleton found beneath a Leicester car park has been confirmed as that of English king Richard III.

Experts from the University of Leicester said DNA from the bones matched that of descendants of the monarch’s family.

Lead archaeologist Richard Buckley, from the University of Leicester, told a press conference to applause: “Beyond reasonable doubt it’s Richard.”

Richard, killed in battle in 1485, will be reinterred in Leicester Cathedral.

Mr Buckley said the bones had been subjected to “rigorous academic study” and had been carbon dated to a period from 1455-1540.

Dr Jo Appleby, an osteo-archaeologist from the university’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History, revealed the bones were of a man in his late 20s or early 30s. Richard was 32 when he died.

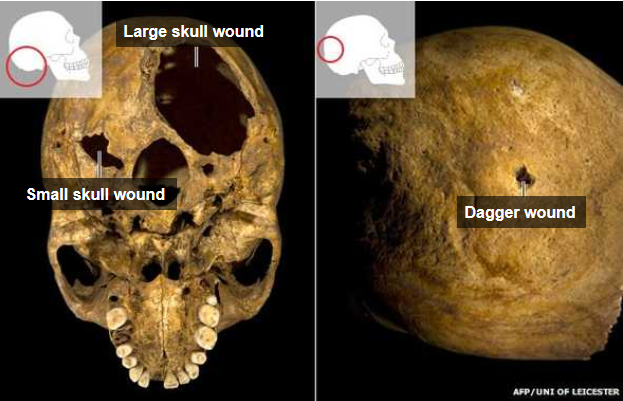

Battle wounds

His skeleton had suffered 10 injuries, including eight to the skull, at around the time of death. Two of the skull wounds were potentially fatal.

One was a “slice” removing a flap of bone, the other caused by bladed weapon which went through and hit the opposite side of the skull, a depth of more than 10cms (4ins).

Dr Appleby said: “Both of these injuries would have caused an almost instant loss of consciousness and death would have followed quickly afterwards.

“In the case of the larger wound, if the blade had penetrated 7cm into the brain, which we cannot determine from the bones, death would have been instantaneous.”

Other wounds included slashes or stabs to the face and the side of the head.

Update: New Scientist still has concerns that the trail of evidence is not strong enough to constitute proof of identity:

Mitochondrial DNA is passed down the maternal line and has 16,000 base pairs in total. Typically, you might expect to get 50 to 150 fragments from a 500-year-old skeleton, says Ian Barnes at Royal Holloway, University of London, who was not involved in the research. “You’d want to get sequences from lots of those fragments,” he says. “There’s a possibility of mitochondrial mutations arising in the line from Richard III.”

“It’s intriguing to be sure,” says Mark Thomas at University College London. It is right that they used mitochondrial DNA based on the maternal line, he says, since genealogical evidence for the paternal lineage cannot be trusted.

But mitochondrial DNA is not especially good for pinpointing identity. “I could have the same mitochondrial DNA as Richard III and not be related to him,” says Thomas.

The researchers used the two living descendents to “triangulate” the DNA results. The evidence will rest on whether Ibsen and his cousin have sufficiently rare mtDNA to make it unlikely that they both match the dead king by chance.