Uploaded on 6 Sep 2011

Sometimes, a body gets a hankering that only Leonard Nimoy singing about hobbits while surrounded by 60’s pixie chicks can sate. Fortunately, we live in a world where those hankerings need not go unfulfilled!

This was originally filmed in 1967, on a variety show called Malibu U. The colour portion of the video is from “Funk Me Up Scotty,” a 1996 documentary from BBC2 about the musical careers of the cast of the original Star Trek. The show cut the last verse and an instrumental/dance interlude, which I’ve restored using black & white footage from I know not where.

February 28, 2015

Leonard Nimoy – The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins

January 26, 2015

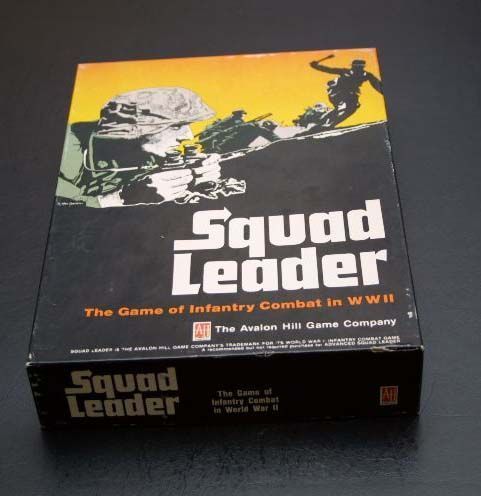

John Hill, RIP

Gerald D. Swick on the death of one of the great wargame designers, the man who created Squad Leader:

If there is a heaven just for game designers, it has a new archangel. John Hill, best known for designing the groundbreaking board wargame Squad Leader, passed away on January 12. He was inducted into The Game Manufacturers Association’s Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design Hall of Fame in 1978; Squad Leader was inducted into the HoF in 2004.

His many boardgame designs include Jerusalem (1975), Battle for Hue (1973), Battle for Stalingrad (1980) and Tank Leader (1986 and 1987), but John was always a miniatures gamer at heart, and anyone who ever got to play a game on his magnificent game table considered themselves lucky. Squad Leader was originally intended to be a set of miniatures rules, but the publisher, Avalon Hill, asked him to convert it to a cardboard-counters boardgame design. His Civil War miniatures rules Johnny Reb were considered so significant that even Fire & Movement magazine, which primarily covered boardgames, published a major article on the JR system. Most recently John designed Across A Deadly Field, a set of big-battle Civil War rules, for Osprey. He completed additional books in the series for Osprey that have not yet been published.

October 22, 2014

“Will the American fashion industry ever tolerate another de la Renta?”

I don’t follow fashion at all, so it hadn’t occurred to me that the recent death of Oscar de la Renta would be much more than a footnote, but Virginia Postrel would disagree:

When fashion designer Oscar de la Renta died Monday, he left neatly resolved two issues that might have otherwise marred his legacy.

The first was the question of who would succeed him. Many a fashion house has been thrown into chaos by the death of its founder. But last week, Oscar de la Renta LLC, the privately held company headed by de la Renta’s stepson-in-law Alex Bolen, said it was appointing Peter Copping, the former artistic director of Nina Ricci, as its creative director. There will be no messy crisis this time.

The second was a matter of state. De la Renta had dressed every first lady since Jacqueline Kennedy — except Michelle Obama. To have the stylish first lady shun the dean of American fashion was tantamount to a public feud. Two weeks ago, the conflict ended when Mrs. Obama wore an Oscar de la Renta dress to a White House cocktail party filled with fashion insiders. Her appearance in the crisply tailored black cocktail dress embellished with silver and blue flowers — a quintessential de la Renta balance of precise lines with ornamentation and color — preserved the designer’s White House legacy.

The clean resolution of these two issues shortly before de la Renta’s passing befits the grace of his life’s work.

But a cultural question remains: Will the American fashion industry ever tolerate another de la Renta? His brand will continue, but the classic elegance for which he was known is as old-fashioned as it is beloved. It defies the prestige accorded to innovators who “move fashion forward” rather than simply creating fresh collections. Michelle Obama wouldn’t have won all those plaudits as a fashion leader if she’d worn his dresses and followed his rules. She would have merely been another tastefully attired Hillary Clinton or Laura Bush.

September 8, 2014

QotD: The Economist‘s whitewash of the “Great Leap Forward”

When Mao died, The Economist wrote:

“In the final reckoning, Mao must be accepted as one of history’s great achievers: for devising a peasant-centered revolutionary strategy which enabled China’s Communist Party to seize power, against Marx’s prescriptions, from bases in the countryside; for directing the transformation of China from a feudal society, wracked by war and bled by corruption, into a unified, egalitarian state where nobody starves; and for reviving national pride and confidence so that China could, in Mao’s words, ‘stand up’ among the great powers.” (emphasis mine)

The current estimate is that, during the Great Leap Forward, between thirty and forty million Chinese peasants starved to death. Critics questioning that figure have suggested that the number might have been as low as two and half million.

I am curious — has the Economist ever published an explicit apology or an explanation of how they got the facts so completely backwards, crediting the man responsible for what was probably the worst famine in history with creating a state “where nobody starves?” Is it known who wrote that passage, and has anyone ever asked him how he could have gotten the facts so terribly wrong?

David D. Friedman, “A Small Mistake”, Ideas, 2014-09-07.

August 13, 2014

Lauren Bacall

In the Telegraph, Tim Stanley says we’ve lost one of the last of the true Hollywood stars:

Lauren Bacall the actor has died, a sad thing for sure. But Lauren Bacall the star will live on forever. Because that’s what stars do. They burn bright for millennia.

Born Betty Perske, a Jewish girl from the Bronx, she was spotted by Howard Hawks’ wife on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar and invited to Hollywood to screen test. Bacall thought Hawks was impressive but scary — it didn’t help that his method of breaking the ice was to make anti-Semitic jokes. Hawks thought Bacall attractive but lumbered with a high-pitched voice that was all wrong for the sophisticated quick-fire dialogue he liked to write. So she drove her car up into the Hollywood hills and practiced speaking low and soft by herself. Next she had to improve her demeanour — and for Hawks this meant turning from a shy girl into a sexually confident one. When she couldn’t get a ride home from a party at Hawks’ house, he told her that men went for women who insulted them. She insulted Clark Gable and, right on cue, he offered to drive her home.

[…]

What defined that character? Friedrich calls it “insolence”. Bacall always played the girl who answered back, the one who had the temerity to ask if a man knew how to whistle. That’s Hollywood censor shorthand for if they knew how to make love. Bacall never went out of her way to please no man; men had to please her. Via a series of noir box office hits, Betty Perske ascended into the pantheon and took the slot of the “sophisticated seductress”. For Golden Age Hollywood dealt not in actors or mere parts, but in stars and archetypes. At any one point there had to be a tough guy, a wise guy, a villain, a maverick. Among women there were the betrayed wives, vamps, innocents and party girls. The name of a star on a movie poster told you everything you needed to know about what would happen in that movie — and you went to see it because the last 48 made in that vein were so darn good. This is the nature of star power, the ability to evoke something with just a name in lights.

May 13, 2014

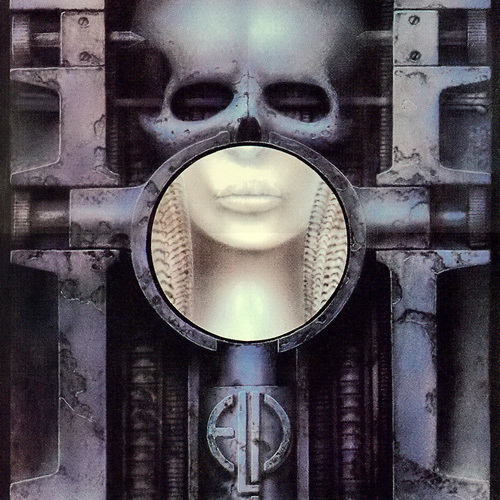

H.R. Giger, RIP

Another unexpected obituary notice today for artist H.R. Giger:

Artist H.R. Geiger sits for an April 1994 portrait in New York City, New York. (Photo by Bob Berg/Getty Images)

In Scientific American, Glendon Mellow talks about Giger’s impact in art:

Hans Ruedi Giger gave us machines moving like flesh. His airbrush compositions are strongly considered to be descendants of Dalí though I have always felt the unease, the dark mirror of the 1890 Symbolists behind his work. If you cracked open the biomechanoid shell, I always assumed the devastating mythologies of Khnopff, Böcklin and Delville would come pouring out. His paintings were the work of sperm, bullet casings, grotty stone and soft cheekbones. It was not made to be beautiful, it was made to unsettle.

Giger’s work unsettled me as a painter and drove me like it did so many others. Are you another painter who paints, in some small way, because of Giger? Share your stories and links to your art in the comments below. Perhaps we will follow-up with a post of art inspired by Giger here on Symbiartic.

Giger is dead. His shadow remains cast over our future. The shadow moves.

I’ve always thought his name was spelled “Geiger”, yet most of the obituaries spell it as “Giger” … but the 1994 image at Getty has it as “Geiger”. I’ve edited this post to use the more common spelling.

Nash the Slash, RIP

CBC News reports that Nash the Slash has died:

He started the independent record label Cut-Throat Records, which he used to release his own music. Among his albums was Decomposing, which he claimed could be listened to at any speed, and Bedside Companion, which he said was the first record out of Toronto to use a drum machine.

His biggest hit was Dead Man’s Curve, a cover of a Jan and Dean song.

More recently, he played at Toronto’s Pride Festival and toured up until 2012. In 1997 Cut-Throat released a CD compilation of Nash the Slash’s first two recordings entitled Blind Windows. In 1999 he released Thrash. In April 2001, Nash released his score to the silent film classic Nosferatu.

Plewman retired in 2012, bemoaning file-sharing online and encouraging artists to be more independent. “It’s time to roll up the bandages,” he wrote.

In the last few years, Plewman also became a vocal supporter of Toronto Mayor Rob Ford.

He will be remembered for his experimental ethos as well as his unusual stage presence.

“I refused to be slick and artificial,” Plewman wrote of his own career.

There has not been word on how the musician died.

H/T to Victor for the link.

Update: Kathy Shaidle has more.

April 10, 2014

Former finance minister Jim Flaherty has died

The former federal finance minister and MP for Whitby-Oshawa (my riding) is reported to have died earlier today:

Jim Flaherty, Canada’s finance minister, smiles while speaking during a press conference after releasing the 2014 Federal Budget on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, on Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2014. Flaherty ramped up efforts to return the country to surplus in a budget that raises taxes on cigarettes and cuts benefits to retired government workers while providing more aid for carmakers. Photographer: Cole Burston/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Former finance minister Jim Flaherty has died. He was 64.

Emergency crews were called to his Ottawa home Thursday afternoon. The cause of death has not been released.

He was one of the longest serving finance ministers Canada has ever had and until he left politics, was the only one to ever serve under Prime Minister Stephen Harper. He stepped down on March 18.

A Conservative MP for the Toronto-area riding of Whitby-Oshawa, Flahery was first elected in 2006.

Flaherty has suffered over the last year from a rare and painful but treatable skin disorder. In his statement, Flaherty said his health did not play a part in his decision to quit politics.

My deepest condolences to his wife Christine Elliot, and their sons John, Galen, and Quinn (Galen and Quinn were players on soccer teams I coached a decade or so back).

March 14, 2014

Iain Martin on the three phases of Tony Benn’s political career

The death of Tony Benn was announced this morning, and the Telegraph‘s Iain Martin says that Benn’s political trajectory had three distinct phases:

The BBC‘s James Landale described it well this morning only minutes after the death of Tony Benn was announced. There were, he told the Today programme, three phases of Tony Benn the public figure. That is right, and in the second phase Benn almost destroyed the Labour Party. His death — or his reinvention as a national treasure from the late 1980s onwards — doesn’t alter that reality.

In the 1950s and 1960s Benn was part of Labour’s supposed wave of the future, serving in Wilson’s governments and embodying the technocratic approach that was going to forge a modern Britain in the “white heat of technology”. It didn’t work out like that.

[…]

But it is when Labour found itself out of power in 1979 that Benn the socialist preacher applied his considerable talents — his gift for public speaking and the denunciation of rivals — to trying to turn Labour, one of Britain’s two great parties that dominated the 20th century, from being a broad church into a party that stood only for his, by then, very dangerous brand of Left-wing extremism. In the wars of that period against Labour’s Right-wing and soft centre he did not operate alone, but he was the figurehead of a Bennite movement that created the conditions in which the SDP breakaway became necessary, splitting the Left and giving Margaret Thatcher an enormous advantage to the joy of Tories. When Labour crashed to defeat in 1983, Benn even said that the result was a good start because millions of voters had voted for an authentically socialist manifesto, which would have taken Britain back to the stone age if implemented.

From there, after a bitter interlude and a sulk, Benn began his final and, this time, wonderful transformation, during which he was elevated to the ranks of national treasure — a pipe-smoking man of letters, like a great National Trust property crossed with George Orwell. As with many journalists of my generation, I encountered him one on one only in that third phase, and found him, as many others did, a deeply courteous, amusing and interesting man. It was his defence of the Commons, against the Executive, that I liked, and when he spoke on such themes it was possible to imagine him at Cromwell’s elbow in the English Civil War, or printing off radical pamphlets before falling out with the parliamentary leadership after the King had had his head cut off.

March 4, 2014

“Comedy turned inward and became domesticated [and] smaller”

In the New York Post, Kyle Smith discusses the comedians of the 1970s and their modern day successors:

As Chevy Chase might have put it on Saturday Night Live, Harold Ramis is still dead. And with him has gone the finest era of comedy: The ’70s kind.

Ramis was as close to the king of comedy as it gets, as a writer, director and occasional sidekick for Animal House, Meatballs, Caddyshack, Stripes, Ghostbusters, Back to School, National Lampoon’s Vacation and Groundhog Day.

[…]

Taking off with the movie M*A*S*H in 1970 — a huge hit that grossed $450 million in today’s dollars — and its spinoff sitcom, ’70s comedy ruled from an anti-throne of contempt for authority in all shapes. College deans, student body presidents, Army sergeants and officers, country-club swells, snooty professors and the EPA: Anyone who made it his life’s work to lord it over others got taken down with wit.

When the smoke bombs cleared and the anarchy died, comedy turned inward and became domesticated. It also became smaller.

The Cosby Show and Jerry Seinfeld didn’t seek to ridicule those in power. Instead they gave us comfy couch comedy — riffs on family and etiquette and people’s odd little habits.

Now, in the Judd Apatow era, comedy is increasingly marked by two worrying trends: One is a knee-jerk belief, held even by many of the most brilliant comedy writers, that coming up with the biggest, most outlandish gross-out gags is their highest calling.

H/T to Kathy Shaidle for the link.

December 11, 2013

The media and the Mandela funeral

In the Guardian Simon Jenkins discusses the way the media covered Nelson Mandela’s funeral:

Enough is enough. The publicity for the death and funeral of Nelson Mandela has become absurd. Mandela was an African political leader with qualities that were apt at a crucial juncture in his nation’s affairs. That was all and that was enough. Yet his reputation has fallen among thieves and cynics. Hijacked by politicians and celebrities from Barack Obama to Naomi Campbell and Sepp Blatter, he has had to be deified so as to dust others with his glory. In the process he has become dehumanised. We hear much of the banality of evil. Sometimes we should note the banality of goodness.

Part of this is due to the media’s crude mechanics. Millions of dollars have been lavished on preparing for Mandela’s death. Staff have been deployed, hotels booked, huts rented in Transkei villages. Hospitals could have been built for what must have been spent. All media have gone mad. Last week I caught a BBC presenter, groaning with tedium, asking a guest to compare Mandela with Jesus. The corporation has reportedly received more than a thousand complaints about excessive coverage. Is it now preparing for a resurrection?

More serious is the obligation that the cult of the media-event should owe to history. There is no argument that in the 1980s Mandela was “a necessary icon” not just for South Africans but for the world in general. In what was wrongly presented as the last great act of imperial retreat, white men were caricatured as bad and black men good. The arrival of a gentlemanly black leader, even a former terrorist, well cast for beatification was a godsend.

[…]

Mandela was crucial to De Klerk’s task. He was an African aristocrat, articulate of his people’s aspirations, a reconciler and forgiver of past evils. Mandela seemed to embody the crossing of the racial divide, thus enabling De Klerk’s near impossible task. White South Africans would swear he was the only black leader who made them feel safe — with nervous glances at Desmond Tutu and others.

South Africa in the early 90s was no postcolonial retreat. It was a bargain between one set of tribes and another. For all the cruelties of the armed struggle, it was astonishingly sparing of blood. This was no Pakistan, no Sri Lanka, no Congo. The rise of majority rule in South Africa was one of the noblest moments in African history. The resulting Nobel peace prize was rightly shared between Mandela and De Klerk, a sharing that has been ignored by almost all the past week’s obituaries. There were two good men in Cape Town in 1990.

December 8, 2013

Mandela’s struggle was not the same as Gandhi’s

Salil Tripathi met Nelson Mandela and finds the frequent comparisons between Gandhi and Mandela to do less than justice to both men:

The South African freedom struggle was different from India’s, and the paths Mandela and Gandhi took were also different. That did not prevent many from comparing him with Gandhi. But the two were different; both made political choices appropriate to their time and the context in which they lived.

Gandhi’s life and struggle were political, but securing political freedom was the means to another end, spiritual salvation and moral advancement of India. Mandela was guided by a strong ethical core, and he was deeply committed to political change. At India’s independence, Gandhi wanted the Congress Party to be dissolved, and its members to dedicate themselves to serve the poor. But the Congress had other ideas. Mandela would not have wanted to dissolve his organization; he wanted to bring about the transformation South Africa needed, but he also wanted to heal his beloved country.

This is not to suggest that Gandhi wasn’t political. He was shrewd and he devised strategies to seek the moral high ground against his opponents — and among the British he found a colonial power susceptible to such pressures, because Britain had a domestic constituency which found colonialism repugnant, contrary to its values.

Mandela’s point was that he didn’t have the luxury of fighting the British — he was dealing with the National Party, with its Afrikaans base, which believed in a fight to finish, seeking inspiration from the teachings of the Dutch Reformed Church which established a hierarchy of different races, which led to the establishment of apartheid. “One kaffir one bullet,” said the Boer (the Afrikaans word for farmer, which many Afrikaans-speaking South Africans were); “One settler one bullet,” replied Umkhonto weSizwe, the militant arm of the ANC.

And yet Mandela’s lasting gift was his power of forgiveness and lack of bitterness. He showed exceptional humanity and magnanimity when he left his bitterness behind, on the hard, white limestone rocks of Robben Island that he was forced to break for years, the harsh reflected glare of those rocks causing permanent damage to his eyes. And yet, he came out, his fist raised, smiling, and he wrote in his memoir, Long Walk To Freedom, that unless he left his bitterness and hatred behind, “I would still be in prison.”

By refusing to seek revenge, by accepting the white South African as his brother, by agreeing to build a nation with people who wanted to see him dead, Mandela rose to a stature that is almost unparalleled.

[…]

Calling Mandela the Gandhi of our times does no favour to either. Gandhi probably anticipated the compromises he would have to make, which is why he shunned political office. Mandela estimated, correctly, that following the Gandhian path of non-violent resistance against the apartheid regime was going to be futile, since the apartheid regime did not play by any rules, except those it kept creating to deepen the divide between people.

H/T to Shikha Dalmia for the link.

December 6, 2013

QotD: Why Mandela was different

Within moments of the announcement that the great man had passed away, left-wingers on twitter gleefully started posting quotes from Reagan-era conservatives about Mandela. At the time, most right-wingers’ opinions of Mandela — with one notable exception — ranged from skepticism to outright hostility. (This William H. Buckley column from 1990, which compares the recently-released Mandela to Lenin, was not atypical.)

Support for apartheid was never justifiable, but when that racist system was in its death throes, it was hardly unreasonable to worry about what might come next. Many political prisoners and “freedom fighters” have eventually come to power in their countries, only to become exactly what they once fought against — or worse. (One of the most infuriating examples is just over the South African border, where the once-promising Robert Mugabe has driven Zimbabwe into the abyss.)

The young Mandela was a revolutionary, and after spending his entire life as a second-class citizen, and 27 years behind bars, any bitterness on his part would have been understandable.

Instead, he chose an unprecedented path of reconciliation:

[…]

The real measure of one’s greatness comes when that person achieves power. And by that standard, Mandela was one of the greatest of them all. May he rest in peace.

Damian Penny, “Why Mandela was different”, DamianPenny.com, 2013-12-06

May 21, 2013

Ray Manzarek, RIP

Musician Ray Manzarek, co-founder of The Doors is dead at 74:

Ray Manzarek, who as the keyboardist and a songwriter for the Doors helped shape one of the indelible bands of the psychedelic era, died on Monday at a clinic in Rosenheim, Germany. He was 74.

The cause was bile duct cancer, according to his manager, Tom Vitorino. Mr. Manzarek lived in Napa, Calif.

Mr. Manzarek founded the Doors in 1965 with the singer and lyricist Jim Morrison, whom he would describe decades later as “the personification of the Dionysian impulse each of us has inside.” They would go on to recruit the drummer John Densmore and the guitarist Robby Krieger.

Mr. Manzarek played a crucial role in creating music that was hugely popular and widely imitated, selling tens of millions of albums. It was a lean, transparent sound that could be swinging, haunted, meditative, suspenseful or circuslike. The Doors’ songs were generally credited to the entire group. Long after the death of Mr. Morrison in 1971, the music of the Doors remained synonymous with the darker, more primal impulses unleashed by psychedelia. In his 1998 autobiography, “Light My Fire,” Mr. Manzarek wrote: “We knew what the people wanted: the same thing the Doors wanted. Freedom.”

May 20, 2013

Neil Reynolds, RIP

Although he was much better known for his career in journalism, I first got to know Neil Reynolds when he joined the Libertarian Party of Canada to contest the 1982 by-election in Leeds-Grenville. Here is his obituary from the Kingston Whig-Standard:

Neil Reynolds is being remembered Sunday night as one of the top editors in Canadian newspaper history, and for being the person responsible for turning the Whig-Standard into a great small-city daily that won national awards and international recognition.

Reynolds died on Sunday in Ottawa. He was 72.

“He was the great editor of Canada from the mid-’70s to the early-2000s because of his ability to improve papers,” said Harvey Schachter, who became editor of the Whig after Reynolds’ departure in 1992.

Reynolds had been city editor of the Toronto Star in 1974 when he suddenly left to return to Kingston and take on an editing job with the Whig-Standard. By 1978 he was planning to move on when publisher and Whig owner Michael Davies offered him the top newsroom job.

Reynolds promptly hired Schachter, Michael Cobden and Norris McDonald to fill out the editors’ ranks.

“The Whig was really the start,” said Schachter. “Why the Whig stood out is he took it from a pretty mundane paper to being the top small-town paper in North America.”

Reynolds’ political career didn’t last long, as he joined the LPC in 1982, held the party leadership for a year, then returned to full-time journalism. His Wikipedia page says that his 13.4% of the vote in that by-election was the highest percentage of the vote achieved by an LPC candidate.