Published on 26 May 2017

The 73 Anniversary of D-Day is nearly upon us so let us talk about the Luftwaffe‘s involvement in the Battle of Normandy!

June 6, 2017

Where was the Luftwaffe on D-Day? – German Response to Operation Overlord, Normandy

July 3, 2015

QotD: “US tankers were notorious for identifying everything as a Tiger tank”

When you read unit accounts, whether it’s the actual unit after action reports or the published books, everyone talks about Tiger tanks. But in looking at it in both German records and US records, I’ve only found three instances in all the fighting from Normandy to 1945 where the US encountered Tigers. And by Tigers I mean Tiger 1, the type of tank we saw in the film [Fury]. I’m not talking King Tigers, the strange thing is that the US Army encountered King Tigers far more often than Tigers. That’s partly because there weren’t a lot of Tigers left by 1944, production ends in August 1944. There were not a lot of Tigers in Normandy, they were mostly in the British sector, the British saw a lot of Tigers. Part of the issue is that US tankers were notorious for identifying everything as a Tiger tank, everything from Stug III assault guns to Panzer IV and Panthers and Tigers.

There was one incident in August of 1944 where 3rd Armored division ran into three Tigers that were damaged and being pulled back on a train, they shot them up with an anti-aircraft half-track. And then there was a single Tiger company up in the Bulge that was involved in some fighting. And then there was one short set of instances in April 1945, right around the period of the film, where there was a small isolated Tiger unit that actually got engaged with one of the new US M26 Pershing tank units. They knocked out a Pershing and then in turn that Tiger was knocked out and the Pershing tanks knocked out another King Tiger over the following days. So I found three verifiable instances of Tigers encountering, or having skirmishes with US troops in 1944-45. So it was very uncommon. It definitely could have happened, there are certainly lots of gaps in the historical record both on the German side and the US side. I think the idea that the US encountered a lot of Tigers during WW2 is simply due to the tendency of the US troops to call all German tanks Tigers. It’s the same thing on the artillery side. Every time US troops are fired upon, it’s an 88, whether it’s a 75mm Pak 40 anti-tank gun, a real 88, a 105mm field howitzer, they were all called 88’s.

“Interview with Steven Zaloga”, Tank and AFV News, 2015-01-27.

June 8, 2015

QotD: German troops on the Atlantic Wall

Formations transferred from the eastern front, especially Waffen-SS divisions, believed that the soldiers garrisoned in France had become soft. “They had done nothing but live well and send things home,” commented one general. “France is a dangerous country, with its wine, women and pleasant climate.” The troops of the 319th Infanterie-Division on the Channel Islands were even thought to have gone native from mixing with the essentially English population. They received the nickname of the “King’s Own German Grenadiers”. Ordinary soldiers, however, soon called it “the Canada Division”, because Hitler’s refusal to redeploy them meant that they were likely to end up in Canadian prisoner of war camps.

Anthony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009.

June 7, 2015

QotD: Air power on D-Day

Allied fighter-bombers continued to attack not only front-line positions, but also any supply trucks coming up behind with food, ammunition and fuel. The almost total absence of the Luftwaffe to contest the enemy’s air supremacy continued to provoke anger among German troops, although they often resorted to black humour. “If you can see silver aircraft, they are American,” went one joke. “If you can see khaki planes, they are British, and if you can’t see any planes, then they’re German.” The other version of this went, “If British planes appear, we duck. If American planes come over, everyone ducks. And if the Luftwaffe appears, nobody ducks.” American forces had a different problem. Their trigger-happy soldiers were always opening fire at aircraft despite orders not to because they were far more likely to be shooting at an Allied plane than an enemy one.

Anthony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009.

June 6, 2015

Canada at War – Normandy, June 1944

Uploaded on 10 Jan 2012

Part 1 of 3

June – September 1944. D-Day, June 6, 1944. In the early morning hours, infantry carriers, including 110 ships of the Royal Canadian Navy, cross a seething, pitching sea to the coast of France, while Allied air forces pound enemy positions from the air. Cherbourg, Caen, Carpiquet, Falaise, Paris are liberated. Canadians return, this time victorious, to the beaches of Dieppe.

H/T to Gods of the Copybook Headings for the link.

QotD: Getting ashore on D-Day

At 04.30 hours on the Prince Baudouin, the waiting soldiers heard the call: “Rangers, man your boats!” On other landing ships there was a good deal of chaos getting the men into the landing craft. Some infantrymen were so scared of the sea that they had inflated their life jackets on board ship and then could not get through the hatches. As they lined up on deck, an officer in the 1st Division noticed that one man was not wearing his steel helmet. “Get your damn helmet on,” he told him. But the soldier had won so much in a high card game that his helmet was a third full. He had no choice. “The hell with it,” he said, and emptied it like a bucket on the deck. Coins rolled all over the place. Many soldiers had their field dressings taped to their helmet; others attached a pack of cigarettes wrapped in cellophane.

Those with heavy equipment, such as radios and flame-throwers which weighed 100 pounds, had great difficulty descending the scramble nets into the landing craft. It was a dangerous process in any case, with the small craft rising and falling and bouncing against the side of the ship. Several men broke ankles or legs when they mistimed their jump or were caught between the rail and the ship’s side. It was easier for those lowered in landing craft from davits, but a battalion headquarters group of the 29th Infantry Division experienced an inauspicious start a little later when their assault craft was lowered from the British ship Empire Javelin. The davits jammed, leaving them for thirty minutes right under the ship’s heads. “During this half-hour,” Major Dallas recorded, “the bowels of the ship’s company made the most of an opportunity which Englishmen have sought since 1776.” Nobody inside the ship could hear their yells of protest. “We cursed, we cried and we laughed, but it kept coming. When we started for shore, we were all covered with shit.”

Anthony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009.

December 27, 2014

Who should have been the allied commanders on D-Day?

Nigel Davies ventures into alternatives again, this time looking at who were the best allied generals for the D-Day invasion (for the record, he’s quite right about the best Canadian corps commander):

The truth is that any successful high command should maximise the chances of success of any campaign by choosing the ‘best fit’ for the job.

But that is not how generals were chosen for D Day.

(I would love to start with divisional commanders, but there are way too many, so for space I will start with Corps and Army commanders, and work up to the top).

The outstanding Canadian of the campaign for instance was Guy Simonds. Described by many as the best Allied Corps commander in France, and credited with re-invigorating the Canadian Army HQ when he filled in while his less successful superior Harry Crerar was sick, Simonds was undoubtedly the standout Canadian officer in both Italy and France.Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, commander of the 2nd Canadian Corps.

He was however, the youngest Canadian division, corps or army commander, and the speed of his promotions pushed him past many superiors. He was also described as ‘cold and uninspiring’ even by those who called him ‘innovative and hard driving’. It can be taken as a two edged sword that Montgomery thought he was excellent (presumably implying Montgomery like qualities?) But his promotions seemed more related to ability than cronyism, and his achievements were undoubted.

Should he have been the Canadian Army commander instead of Crerar? Yes. Arguments against were mainly his lack of seniority, and lack of experience. but no Canadian had more experience, and lack of seniority was no bar in most of the other Allied armies.

It comes down to the simple fact that the Allied cause would have been better served by having Simonds in charge of Canadian forces than Crerar.

Simonds was a brilliant corps commander and (at least) a very good army commander, but he had one fatal flaw: he was no politician. Harry Crerar was a very “political” general, and played the political game with far greater talent than any other Canadian general. That got him into his role as army commander and his political skills kept him there despite the better “military” options available.

October 14, 2014

Hastings, 1066? Think of it as a real-world model of Game of Thrones

In the Telegraph, Dominic Selwood explains the Norman Invasion of 1066 and the many shades of grey (or red) that are missing from the traditional story of the rise of the Normans:

As we wait for the next series of Game of Thrones, I cannot help but think I have seen it all before — dynastic families so intermarried that the members’ only loyalty is to self; ambitions so uncompromising that war is the inevitable result; and carnage so total that the threat of defeat is existential. But whenever the story takes me to the throne room in the Red Keep at King’s Landing, all I see is Westminster Abbey — because this is an old, old story.

We like to think that Anglo-Saxon England was brutally cut down in 1066 — unexpectedly — in a battle lasting just one day. To reinforce our assumptions, we still revel in Victorian and Hollywood melodrama stereotypes of dastardly Normans persecuting flaxen Saxons in box-sets of Ivanhoe or Tolkein’s thinly disguised versions set in Middle Earth.

The reality, of course, is far more complex.

[…]

The road to Hastings began ordinarily enough. A man lay dying. As it happened, it was Edward the Confessor. But what marked the event out as singular was that he had failed in one of his key royal responsibilities — he was leaving the world childless. To no one’s surprise, as the end approached, he nominated as heir his brother-in-law, the 46-year-old Earl Harold Godwinson of Wessex.

Harold was the kingdom’s richest noble, and a great military commander who had subjugated Wales in 1063. The Witenagemot promptly proclaimed him king, and Archbishop Stigand of Canterbury crowned him at Edward’s gleaming new Westminster Abbey the following day, the 6th of January 1066, the same day Edward was buried there.

But the dead king’s ineffectual leadership had passed Harold a major headache, as one of Edward’s favourite political strategies had been to promise all sorts of people he would make them his heir. Given his strong attachment to Normandy, it is no surprise that he had, most likely in 1051, promised the throne to Duke William of Normandy, a distant cousin. In fact, Norman sources go further, saying that in 1064 Edward had even sent Harold to Normandy to confirm the arrangement. At the same time, in front of William and on a box of relics, Harold apparently swore a sacred oath to uphold William’s claim to the English throne.

The headache did not end with William. There were other claimants, too. King Harald III “Hardraada” (the ruthless) of Norway had a claim to the throne via an earlier agreement between Harthacnut (king of England and Denmark) and Magnus I (king of Norway and Denmark). Over in Hungary, Edgar the Ætheling had a claim as grandson of King Edmund II “Ironside”. And in exile in Flanders and Normandy, Tostig Godwinson, Harold’s rebellious brother, was nursing a venomous grievance against the Anglo-Saxon establishment.

July 6, 2014

Henry II – “from the Devil he came, and to the Devil he will surely go”

Nicholas Vincent looks at the reign of King Henry II, the founder of the Plantagenet dynasty who died on this day in 1189:

Although in December 1154, Henry was generally recognised as the legitimate claimant to the throne, most notably by the English Church, his accession was fraught with perils. Among the Anglo-Norman aristocracy there were many who saw Henry as an outsider: an Angevin princeling, descended via his father, Count Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou, from a dynasty that had long been regarded as the principal rival on Normandy’s southern frontier. King Stephen had left a legitimate son, William Earl Warenne, still living in 1154, and Henry himself had two younger brothers who might well have disputed his claims to succeed to all his family’s lands and titles. Asked some years before to judge Henry’s chances of success, St Bernard of Clairvaux is said to have predicted of Henry that ‘from the Devil he came, and to the Devil he will surely go’.

Yet, from what contemporaries termed ‘the shipwreck’, and modern historians have described as ‘the anarchy’ of Stephen’s reign, Henry II was to emerge as one of England’s, indeed as one of Europe’s, greatest kings. The Plantagenet dynasty that he founded was to occupy the throne of England through to 1399 and the eighth successive generation. Henry himself came to rule over the most extensive collection of lands that had ever been gathered together under an English king – an empire in all but name, that stretched from the Cheviots to the Pyrenees, and from Dublin in the west to the frontiers of Flanders and Burgundy in the east.

In part this empire was the product of dynastic accident. From his mother, Matilda, daughter and sole surviving legitimate child of the last Anglo-Norman King, Henry inherited his claim to rule as king in England and as duke in Normandy. From his father, Geoffrey, he succeeded to rule over Anjou, Maine and the Touraine: the counties of the Loire valley that had previously blocked Anglo-Norman ambitions in the South. Rather than share these inherited spoils with his brothers, Henry seized everything for himself. William, his younger brother, was granted a rich but by no means royal estate. Geoffrey, the third brother, threatened rebellion but was bought off with a shortlived grant of the county of Nantes.

Henry, however, was far more than just a fortunate or crafty elder son. Through his own exertions he greatly expanded his family’s territorial claims. In 1152, two years before obtaining the throne of England, he had married Eleanor, heiress to the duchy of Aquitaine and only a few weeks earlier divorced from her previous husband, the Capetian King Louis VII. As effective ruler of Eleanor’s lands, Henry found himself in possession of a vast estate in south-western France, stretching from the Loire southwards through Poitou and Gascony to the frontiers of Spain. Henry’s marriage to Eleanor was regarded as scandalous even by his own courtiers. She was eleven years older than him and was rumoured to have enjoyed extra-marital affairs not only with her own uncle but with Henry’s father, Geoffrey Plantagenet. By temperament she was as fiery as Henry, and as determined to stake her own claims to rule. As a result, Henry’s domestic life was far from tranquil. From 1173 onwards, Eleanor was to be held under house arrest in England, whilst Henry, to judge by the bastard children that he fathered, had long enjoyed the favours of a series of mistresses. Even so, by his marriage, Henry laid the basis of the later claims made by England’s kings to rule over southern France: claims that were to unite Gascony to the English crown as late as the fifteenth century and which were to play a vital role in the history of Anglo-French relations throughout the Middle Ages and beyond.

July 5, 2014

QotD: Collaborators and their accusers, France 1944

The task of filtering the tens of thousands of Frenchmen and women arrested for collaboration in the summer of 1944 proved overwhelming for the nascent administration of de Gaulle’s provisional government. That autumn, there were over 300,000 dossiers still outstanding. In Normandy, prisoners were brought to the camp at Sully near Bayeux by the sécurité militaire, the gendarmerie and sometimes by US military police. There were also large numbers of displaced foreigners, Russians, Italians and Spaniards, who were trying to survive by looting from farms.

The range of charges against French citizens was wide and often vague. They included “supplying the enemy”, “relations with the Germans”, denunciation of members of the Resistance or Allied paratroopers, “an anti-national attitude during the Occupation”, “pro-German activity”, “providing civilian clothes to a German soldier”, “pillaging”, even just “suspicion from a national point of view”. Almost anybody who had encountered the Germans at any stage could be denounced and arrested.

Anthony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009.

June 6, 2014

1st Canadian Parachute Battalion War Diary

Excerpt from 6 June, 1944:

6th June 1944

Place: Carter Bks, Bulford

The initial stages of operation OVERLORD insofar as the 1st. Cdn. Parachute Battalion was concerned, were divided into three tasks. The protection of the left flank of the 9th Para Battalion in its approach march and attack on the MERVILLE battery 1577 was assigned to “A” Company. The blowing of two bridges over the RIVER DIVES at 1872 and 1972 and the holding of feature ROBEHOMME 1873 was assigned to “B” Company with under command one section of 3 Para Sqdn Engineers. The destruction of a German Signal Exchange 1675 and the destruction of bridge 186759 plus neutralization of enemy positions at VARRAVILLE 1875 was assigned to “C” Company.

The Battalion was to drop on a DZ 1775 in the early hours of D Day, “C” Company dropping thirty minutes before the remainder of the Battalion to neutralize any opposition on the DZ. The Battalion emplaned at Down Ampney Airfield at 2250 hours on the 5th June, 1944. “C” Company travelled in Albemarles and the remainder of the Battalion in Dakotas (C-47). The flight was uneventful until reaching the French coast when a certain amount of A.A. fire was encountered. Upon crossing the coast-line numerous fires could be seen which had been started by the R.A.F. bombers. Unfortunately the Battalion was dropped over a wide area, some sticks landing several miles from their appointed R.V.. This factor complicated matters but did not deter the Battalion from securing its first objectives.

Protection of Left Flank of 9 Para Bn – A Company

“A” Company was dropped at approximately 0100 hours on the morning of 6th June, 1944. Lieut. Clancy, upon reaching the Company R.V. found only two or three men of the Company present. After waiting for further members, unsuccessfully, of the Company to appear, he decided to recce the village of GONNEVILLE SUR-MERVILLE 1676. Taking two men he proceeded and penetrated the village but could find no sign of the enemy. He then returned to the Company R.V. which he reached at approximately 0600 hours and found one other Officer and twenty Other Ranks of the Battalion and several men from other Brigade Units waiting. The entire body then moved off along the pre-arranged route to the MERVILLE battery. Encountering no other opposition enroute other than heavy R.A.F. Bombardment at GONNEVILLE SUR-MERVILLE. Upon completion of the 9th Battalion task the Canadian party acted first as a recce patrol to clear a chateau 1576 from which a German M.G. had been firing and then acted as a rear guard for the 9th Battalion withdrawal toward LE PLEIN 1375. The party left the battalion area (9th Battalion) at LE PLEIN at 0900 hours and reached the 1st Cdn. Para. Bn. position at LE MESNIL BAVENT cross roads 139729 at 1530 hours on the 6th June, 1944.ROBEHOMME – “B Company

Two platoons of “B” Company were dropped in the marshy ground south and west of ROBEHOMME. Elements of these platoons under Sgt. OUTHWAITE then proceeded toward the Company objective. Enroute they encountered Lieut. TOSELAND with other members of “B” Company making a total of thirty All Ranks. They were guided through the marshes and enemy minefields to the ROBEHOMME bridge by a French Woman. On arriving at the bridge they met Capt. D. GRIFFIN and a further thirty men from various sub-units of the Battalion, including mortars and vickers Platoons. MAJOR FULLER who had been there for some time left in an attempt to locate Battalion Headquarters. Capt. GRIFFIN waited until 0630 hours for the R.E.’s who were to blow the bridge. As they failed to arrive explosives were collected from the men and the bridge successfully demolished.

A guard was left on the bridge and the main body withdrawn to the ROBEHOMME hill. Although there were no enemy in the village there were several skirmishes with enemy patrols who were attempting to infiltrate through the village and some casualties were suffered by the Company. An O.P. was set up in the church spire. An excellent view was obtained of the road from PONT DE VACAVILLE 2276 to VARRAVILLE. Artillery and infantry could be seen moving for many hours along this road from the East. It was particularly unfortunate that wireless communication could not be made with Bn. H.Q. as the subsequent fighting of the Battalion was carried out in such close country that observation of enemy movement was almost impossible.

At 1200 hours on the 7th June, 1944, it was decided to recce the route to Bn. H.Q.. Upon the route being reported clear orders were issued for the party to prepare to join Bn. H.Q. Lieut. I. WILSON, Bn. I.O. came from LE MESNIL to guide the party back. The move was made at 2330 hours, the strength of the party by this time being 150 All Ranks, the addition having been made by stragglers of various units who had reported in. The wounded were carried in a civilian car given by the cure, and a horse and cart given by a farmer. The route was BRIQUEVILLE 1872 to BAVENT road 169729, through the BOIS DE BAVENT and on to LE MESNIL cross roads. Near BRIQUEVILLE the lead platoon was challenged by enemy sentries. The platoon opened fire killing seven and taking one prisoner. Shortly afterwards this same platoon was fortunate enough to ambush a German car which was proceeding along the road from BAVENT. Four German Officers were killed. Bn. Headquarters was reached at 0330 hours on the 8th June, 1944.

VARRAVILLE – “C” Company

The majority of “C” Company was dropped west of the RIVER DIVES, although some sticks were dropped a considerable distance away including one which landed west of the RIVER ORNE. Due to this confusion the company did not meet at the R.V. as pre-arranged but went into the assault on the Chateau and VARRAVILLE in separate parties. MAJOR McLEOD collected a Sgt. and seven O.R.’s and proceeded towards VARAVILLE. En route they were joined by a party under Lieut. WALKER. One of the Sgts. was ordered to take his platoon to take up defensive positions around the bridge that the R.E. sections were preparing to blow. This was done and the bridge was successfully demolished.

MAJOR McLEOD and Lieut. WALKER with the balance of the party then cleared the chateau and at the same time other personnel of “C” Company arrived from the DZ and cleared the gatehouse of the chateau. The gatehouse then came under heavy M.G. and mortar fire from the pill box situated in the grounds of the chateau. The pill-box also had a 75 mm A/Tk. Gun. The whole position was surrounded by wire, mines and weapon pits. MAJOR McLEOD, Lieut. WALKER and five O.R.’s went to the top floor of the gatehouse to fire on the pillbox with a P.I.A.T. the enemy 75mm A/Tk. Gun returned fire and the shot detonated the P.I.A.T. ammunition. Lieut. WALKER, CPL. OIKLE, PTES. JOWETT and NUFIELD were killed and MAJOR McLEOD and PTE. BISMUKA fatally wounded. PTES. DOCKER and SYLVESTER evacuated these casualties under heavy fire. CAPT. HANSON, 2 i/c of “C” Company was slightly wounded and his batman killed while proceeding to report to the Brigade Commander who had arrived in the village from the area in which he dropped. “C” Company, together with elements of Brigade H.Q. and the R.E.’s took up defensive positions around the village and a further party encircled the pill-box in order to contain the enemy. A further party of “C” Company under Lieut. McGOWAN who had been dropped some distance from the DZ arrived in VARAVILLE in time to catch two German Infantry Sections who were attempting to enter the town. Lieut. McGOWAN’s platoon opened fire causing casualties and the remainder of the enemy surrendered. This platoon took up firing positions firing on the enemy pill-box. “C” Company H.Q. which was located in the church yard pinned an enemy section attempting to advance in a bomb crater killing at least three. The chateau was evacuated by our troops and left as a dressing station. An enemy patrol re-entered the chateau and captured the wounded including Capt. BREBNER, the Unit M.O., and C.S.M. Blair of “B” Company. This patrol although attacked by our own troops managed to escape with their prisoners.

Heavy enemy Mortar Fire and sniping was brought to bear on our positions from the woods surrounding VARAVILLE. During this time the local inhabitants were of great assistance, the women dressing wounds and the men offering assistance in any way. One Frenchman in particular distinguished himself. Upon being given a red beret and a rifle he killed three German Snipers. This man subsequently guided the Brigade Commander and his party towards LE MESNIL. Although it is believed he was a casualty of the bombing attack that caught this party enroute to LE MESNIL.

At approximately 1030 hours the enemy pill-box surrendered. Forty-two (42) prisoners were taken and four of our own men who had been captured were released. From 1230 hours on artillery fire was brought to bear on VARAVILLE from the high ground east of the RIVER DIVES. At 1500 hours cycle troops of the 6th Commando arrived and at 1730 hours on 6 June, 1944, “C” Company proceeded to the Bn. area at LE MESNIL. The german prisoners giving evident satisfaction to the French population enroute.

VICKERS PLATOON – Initial Stages

The Vickers platoon was dropped in four sticks of ten or eleven each being a total of forty-one (41) All Ranks. For the first time their M.G.’s were carried in Kit Bags, a number of which tore away and were lost.

The Platoon was dropped over a wide area, a part of them joining “C” Company’s attack on VARAVILLE, part joining “B” Company at ROBEHOMME and part joining Bn. H.Q.. Casualties on the drop totalled twelve missing and three wounded. One of the missing, PTE. PHIPPS, was identified in a photo in a German newspaper found on a P.W. After the initial Company tasks had been accomplished the platoon was deployed to the Companies as single gun detachments or as Sections.

MORTAR PLATOON – Initial Stages

The Mortar Platoon was dropped over a wide area and suffered very heavy loss in equipment due to kit bags breaking away and a great majority of the men landing in marshy ground. As the platoon dropped they attached themselves to the nearest company they could find and assisted in the capture of the objectives. One detachment commander landed on top of the German pill-box at VARAVILLE. He was made prisoner and spent the rest of the time in the pill-box until the Germans surrendered to “C” Company. A point of interest was that the P.I.A.T. Bombs did definite damage to the interior of the pill-box and had a very towering effect upon the morale of the defenders.

Some of the Mortar Platoon which joined “B” Company at ROBEHOMME were detailed to guard the approaches to the destroyed bridge. Three enemy lorries full of infantry appeared on the other side of the bridge. The guard opened fire knocking out one truck killing most of its occupants. The other two lorries were able to withdraw. One of our own men who was a prisoner in the lorry was able to make good his escape.

Upon the detachments arriving at LE MESNIL they were re-grouped as a platoon and given three mortars which had arrived by sea. These mortars were set up in position in the brickworks where they engaged the enemy.

BATTALION HEADQUARTERS – Initial Stages

The Commanding Officer, 2 i/c, Signals Officer and the Intelligence Officer and a small portion of the Battalion Headquarters together with elements of 224 Para Fd. Ambulance and other Brigade Units met at the Battalion R.V. in the early hours of the morning of 6th June, 1944. The Signals Officer was detailed to look after the Enemy Signal Exchange near the R.V.. He went into the house and found a certain amount of Signals equipment which he destroyed but he found no Germans. The Intelligence Officer set out with two men to recce VARAVILLE and bring back a report on the situation. In the Battalion Headquarters meantime the party moved off to LE MESNIL taking with them many scattered elements including a 6 Pdr. A/Tk. Gun and crew. Upon reaching the Chateau 1574 they encountered part of the Brigade Headquarters. The party there upon split up into unit parties and continued until they reached the orchards 141729 where they came under heavy sniping fire from nearby houses. This fire caused several casualties including one Officer. The enemy were forced to withdraw from the buildings after an attack by the party. The party reached the Battalion area at approximately 1100 hours on 6th June, 1944.

H/T to @LCMSDS for the link.

Update: War diaries for units in the 3rd Canadian Division in Normandy can be read here.

Mulberries, PLUTO and Hobart’s Funnies

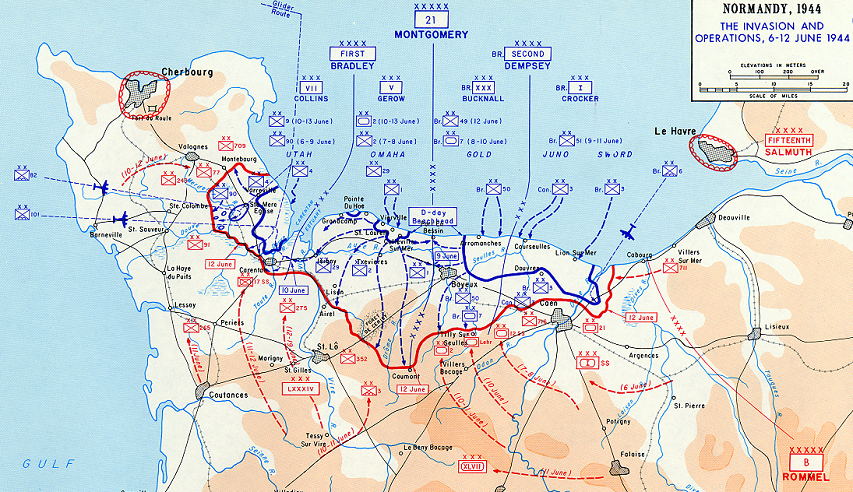

Seventy years ago today, the Allies launched Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy by the combined British, American, and Canadian armies. A huge fleet of combat and transport vessels, supported by a large proportion of the United States Army Air Force and the Royal Air Force bomber and fighter aircraft were all deeply involved in making the invasion a success. In addition, perhaps the world’s largest disinformation campaign was being run to keep the German high command unsure of the real time and location of the invasion: the Pas de Calais and the Norwegian coast were also potential invasion targets, forcing the defenders to spread their forces thinner and to keep as many as possible out of reach of the real beaches.

In addition to the operational uncertainty of where to expect the blow, the Germans were also split about how best to conduct the defence: Field Marshal Rommel wanted to rush units to the beach as soon as possible, to defeat the Allies before they got inland. General Geyr von Schweppenburg, commander of Panzer Group West (and Field Marshal von Rundstedt, overall commander in the West), on the other hand, preferred to meet the Allies further inland (not taking the full impact of Allied air superiority into account). On 6 June, the defenders fell between the two philosophies, not being able to mass enough force to stop the invaders in their tracks, but suffering higher casualties in the attempt to move units toward the coast in the teeth of RAF/USAAF attacks.

The invasion beaches were code-named Utah (4th US Division), Omaha (1st and 29th US divisions), Gold (50th British Division), Juno (3rd Canadian Division), and Sword (3rd British Division). Before the amphibious forces landed, three paratroop divisions were dropped behind the beaches to slow down German response (US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to the West and Southwest of Utah beach, and the 6th British Airborne to the East of Sword beach).

One thing to note from the map is that there wasn’t a significant port within the invasion zone: the Allies had learned the bitter lessons of attacking a port in August of 1942 and the 2nd Canadian Division had paid in blood for the tuition. This meant a way had to be found to keep getting supplies to the troops after they moved off the beaches, until a functioning port could be secured. The Allied answer was to bring a port with them from England — two of them, actually — one to support the US forces in the West and one to support the British and Canadian forces in the East. These were the Mulberry harbours:

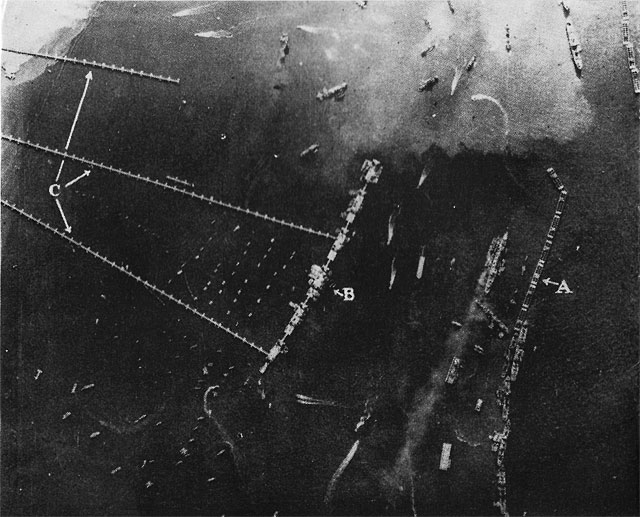

Think Defence explains how the Mulberry harbour worked:

In the image above these three components are shown.

A; Breakwater to attenuate waves

B; Pier heads at which to load and unload

C; Causeways that connected the pier heads to the beach

Each of the components was given a code word but fundamentally, they were concerned with either providing sheltered water or connecting ships and the beach.

There have been a number of different theories about how the Mulberry name was chosen, the more fanciful ones being completely incorrect.

Brigadier White recalls the moment he received a memo, unclassified, with the heading ‘Artificial Harbours’ and after recovering from the shock of such poor security immediately consulted with the Head of Security at the War Office. The next code, from the big book of code words, was Mulberry, it was that simple.

[…]

There were two complete Mulberry harbours, A for American and B for British, each the size of Dover harbour. Once the task of constructed and assembling the components on the South coast of England was complete they were ordered to Normandy on the 6th of June 1944, D-Day, departing on the 7th

Assembling the components was an effort in itself, requiring 600 tugs drawn from all parts of the UK and USA, all under the supervision of the Admiralty Towing Section commanded by Rear Admiral Brind.

Operational security was paramount, the captains of the block ships were told they were going to the Bay of Biscay and a model of the Mulberry harbour and invasion beaches in the headquarters of the Automobile Association at Fanum House was made by toymakers who were confined to the building until well after the invasion.

Unfortunately, the Western harbour was severely damaged in a storm a few weeks after coming into service, so the Eastern Mulberry had to do double duty after that.

Aside from the need to get reinforcements, rations, ammunition and other supplies forward, the Allied armies were highly motorized, and required vast amounts of fuel. Without a port’s specialized unloading facilities, it was assumed that it would be somewhere between difficult and impossible to keep the armies mobile. To address this, PLUTO was developed: Pipe Line Under The Ocean.

A great solution, although as Think Defence points out, it didn’t actually go into service until a few months after D-Day, and was not quite the war-winner the newsreel portrayed:

Second in daring only to the artificial harbors project and provided our main supplies of fuel during the Winter and Spring campaigns.

What also PLUTO did was allow vital tanker tonnage to be deployed to the Far East theatre.

Despite the understandable over exaggeration of the success of PLUTO it should be noted that fuel did not start flowing until September 1944, well after the invasion and on the 4th of October, BAMBI was closed down and operations concentrated on DUMBO after it had delivered a measly 3,300 tonnes, hardly war winning.

Cherbourg was by then receiving tanker supplies direct from the USA.

Getting across the channel was a major undertaking, but getting the troops ashore with enough firepower to break out of the beach defences required more innovation. The British army established a specialized unit to develop and operate vehicles and weapon systems specifically designed for that purpose. Major General Sir Percy Hobart was the commander of the 79th Armoured Division, and he was exactly the right man for the job (being related by marriage to Montgomery may have helped, too, but before taking command he was acting as a corporal in the Home Guard).

Getting across the channel was a major undertaking, but getting the troops ashore with enough firepower to break out of the beach defences required more innovation. The British army established a specialized unit to develop and operate vehicles and weapon systems specifically designed for that purpose. Major General Sir Percy Hobart was the commander of the 79th Armoured Division, and he was exactly the right man for the job (being related by marriage to Montgomery may have helped, too, but before taking command he was acting as a corporal in the Home Guard).

Hobart’s unit developed some of the most interesting armoured vehicles (not all of which were brilliant successes) and it’s safe to say that the Allies would have suffered much higher casualties without Hobart’s “Funnies”. In fact, General Eisenhower said as much himself: “Apart from the factor of tactical surprise, the comparatively light casualties which we sustained on all beaches, except OMAHA, were in large measure due to the success of the novel mechanical contrivances which we employed, and to the staggering moral and material effect of the mass of armor landed in the leading waves of the assault. It is doubtful if the assault forces could have firmly established themselves without the assistance of these weapons.” Think Defence has a good summary of many of these odd and interesting vehicles:

Sherman tanks were also converted into amphibious vehicles by the addition of a canvas skirt, propellers and other modifications. These provided vital armoured fire support in the opening phase of the beach assault although a number were lost to the heavy seas when they were launched too far from the beach. It is widely thought that as these losses were particularly heavy on Omaha beach it was this that contributed to the very high losses in that area.

Mine clearance was carried out by a number of means but the preferred method was to use rotating chain flails to detonate the mines thus clearing a path the width of the tank. The flails were mounted on the front of the tank and were called Sherman Crabs. A number of Churchill based designs using rollers and ploughs were also employed, although this image shows one mounted on a Sherman.

The beach surveys had revealed the existence of large patches of clay that would not bear the weight of heavy vehicles and artillery. To overcome this the ‘bobbin’ tanks were used that laid a continuous reinforced canvas mat over the soft ground, thus spreading the load over a wider area.

Canadian paratroopers on D-Day – “he thought we were battle hardened and we were as green as green could be”

Lance Corporal John Ross tells the Ottawa Citizen about his D-Day experiences with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion:

“We attacked the strong point; there was an all-night fire fight. We had casualties and the Germans did too. At about 10 o’clock in the morning they surrendered. There were about 30 of us there, 42 Germans surrendered to us. They outnumbered us and they out gunned us,” describes Capt (Ret) John Ross, now 93 years-old recalling his time as a paratrooper who dropped several kilometers inland of Normandy on D-Day.

“We took off on the 5th of June, one day before D-Day. C Company was given the job to go in 30 minutes ahead to clear the drop zone of any enemy and attack the German complex.”

Capt (Ret) Ross served as a Lance Corporal in C Company, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, 3rd Airborne Brigade, 6th British Airborne Division. He was dropped from an Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle, a small two engine paratroop transport aircraft.

[…]

When thinking back to his time in Normandy Capt (ret) Ross remembers how Canadian soldiers were thought of as, seasoned warriors.

“I read an excerpt written by a German General after the war. He was in that area that we dropped in and he said that the reason they were overcome was because they faced battle hardened Canadians. I’d like to write a letter to him and say none of those Canadians had ever heard a shot fired in anger; he thought we were battle hardened and we were as green as green could be.”

June 6, 2013

D-Day 1942 or 1943

At Military History Now, there’s a look at a few of the allied plans for invading France before the actual June 6, 1944 operation:

IKE’S SLEDGEHAMMER

Almost as soon as America entered the war with Nazi Germany, generals Dwight Eisenhower and George Marshall were both lobbying for a strike across the English Channel into France. One plan foresaw a joint British and American assault on either of the French port cities of Cherbourg or Brest as early as the fall of 1942. The operation, codenamed Sledgehammer, would see a force of just six divisions attack, capture and hold either one of the two strategically-vital, deep-water harbours. The force, which likely would have totalled no more than 60,000 men, would have been expected to withstand the inevitable Nazi counterattacks until spring when more reinforcements could arrive. Despite the fact that the Germans would have been free to throw as many as 30 divisions at the invaders, the U.S. Joint Chiefs (as well as the Soviets) endorsed Sledgehammer wholeheartedly. The American commanders seemed to favour any plan that would bring U.S. forces into action in Europe quickly, while Stalin was thrilled at the prospect of an Allied offensive in Western Europe — anything to divert German forces away from the Russian front. Oddly enough, while the mission called for the heavy use of American air and sea power, at the time there was still only a handful of combat-ready U.S. Army units in England. As such, the ground portion of the invasion would be left entirely up to the British military. Cooler heads, namely Prime Minister Churchill, convinced Eisenhower to shelve Sledgehammer – Britain was already stretched thin in Egypt and America still had yet to fully mobilize for the war in Europe. An invasion of France would simply have to wait.OPERATION ROUNDUP

Later in 1942, the Allies roughed out a second plan to put troops ashore in Western Europe the following spring. This operation, dubbed Roundup, called for 18 British and 30 American divisions to hit a series of landing zones along a 200 km stretch of coastline between Boulogne-sur-Mer near Calais and the port of Le Harve. Overhead, more than 5,700 Allied aircraft were to sweep the skies of the Luftwaffe clearing the way for a series of airborne drops. D-Day was set for some time in April or May of 1943. The British, already strained by three years of total war against the Axis, were understandably reluctant to throw their army headlong into the teeth of Germany’s Channel fortifications. They pushed instead to attack Sicily and Italy – what Churchill called the “soft underbelly of Europe” — by way of North Africa. A sober appraisal of British and American fleet strength, air assets and manpower ultimately convinced the Allied high command that no invasion could be mounted until 1944 at the earliest. For one thing, American factories had yet to manufacture enough of the landing craft needed for such a massive undertaking. Washington and London turned their attention instead towards a late 1942 invasion of Tunisia – Operation Torch. The rest is, as they say, history.

As any Canadian military historian would probably have said to either of these proposals … I have two words: Operation Jubilee.

The Dieppe Raid, also known as the Battle of Dieppe, Operation Rutter and, later, Operation Jubilee, was a Second World War Allied attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe. The raid took place on the northern coast of France on 19 August 1942. The assault began at 5:00 a.m. and by 10:50 a.m. the Allied commanders were forced to call a retreat. Over 6,000 infantrymen, predominantly Canadian, were supported by a Canadian Armoured regiment and a strong force of Royal Navy and smaller Royal Air Force landing contingents.

The objective of the raid was discussed by Winston Churchill in his war memoirs:

“I thought it most important that a large-scale operation should take place this summer, and military opinion seemed unanimous that until an operation on that scale was undertaken, no responsible general would take the responsibility of planning the main invasion…

In discussion with Admiral Mountbatten it became clear that time did not permit a new large-scale operation to be mounted during the summer (after Rutter had been cancelled), but that Dieppe could be remounted (with the new code-name “Jubilee”) within a month, provided extraordinary steps were taken to ensure secrecy. For this reason no records were kept but, after the Canadian authorities and the Chiefs of Staff had given their approval, I personally went through the plans with the C.I.G.S., Admiral Mountbatten, and the Naval Force Commander, Captain J. Hughes-Hallett.”

Objectives included seizing and holding a major port for a short period, both to prove it was possible and to gather intelligence from prisoners and captured materials, including naval intelligence in a hotel in town and a radar installation on the cliffs above it. Although the primary objective was not met and secondary successes were relatively few, some knowledge was gained while assessing the German responses. The Allies also wanted to destroy coastal defences, port structures and all strategic buildings. Due to the failure to secure Dieppe this objective was not met in any systematic sense. The raid had the added objective of providing a morale boost to the troops, Resistance, and general public, while assuring the Soviet Union of the commitment of the United Kingdom and the United States.

A total of 3,623 of the 6,086 men (almost 60%) who made it ashore were either killed, wounded, or captured. The Royal Air Force failed to lure the Luftwaffe into open battle, and lost 96 aircraft (at least 32 to flak or accidents), compared to 48 lost by the Luftwaffe.[2] The Royal Navy lost 33 landing craft and one destroyer. The events at Dieppe later influenced preparations for the North African (Operation Torch) and Normandy landings (Operation Overlord).

Operation Jubilee clearly showed that the plans for both Sledgehammer and Roundup would have been bloody failures.

November 9, 2012

Deception and counter-deception

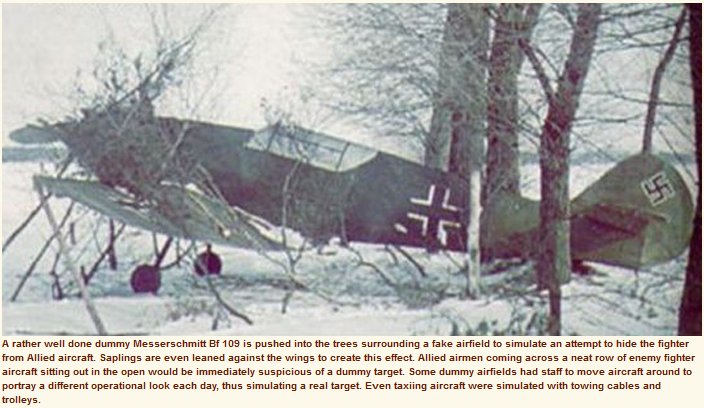

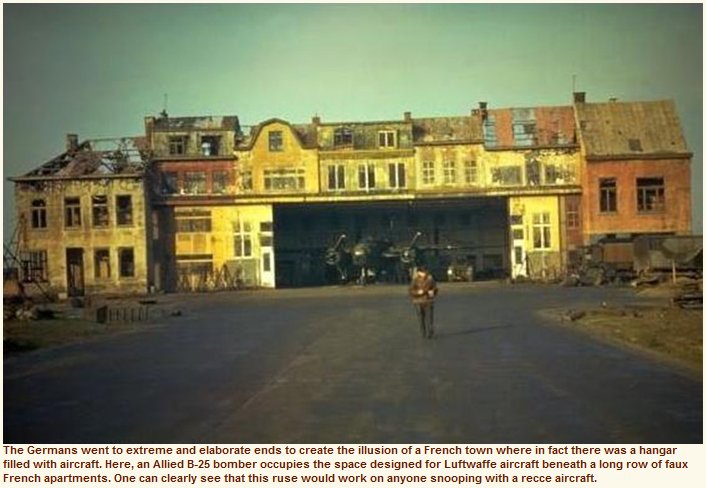

Deception in war reached a crescendo in the latter stages of World War 2, with the allies’ use of General George S. Patton’s imaginary First US Army Group (FUSAG) to pin German attention on the Pas de Calais for more than a month after the real D-Day landings in Normandy. In addition to direct propaganda and an extensive radio network generating fake messages to show the size of FUSAG, the allies also created entire dummy airfields and flotillas of fake landing craft to show up on German air recon photos. The fake planes, aircraft, and buildings were a key part of maintaining the fictitious threat of another, bigger invasion — which successfully kept a large German force away from the real landings.

Less well-known is that the Germans also indulged in this kind of deception:

In what could easily be the finest and boldest example of death-defying and cheeky nose-thumbing during the Second World War or any conflict for that matter, bomber and intruder crews of the Royal Air Force and USAAF are reputed to have bombed the Luftwaffe’s decoy airfields and dummy aircraft, not with high explosives or incendiaries, but with nothing more than dummy bombs made of wood, and painted with the smug remark “Wood for Wood”… all just to make a point.

Throughout all theatres of war, during the Second World War, from China to Holland to Kent, air forces, phsy-ops units and logistics people constructed dummy targets such as airfields, factories, truck parks, convoys and even ships, out of wood, canvas, burlap, or inflatable rubber. The decoy airfields were often populated with dummy aircraft and vehicles of such high quality, that even low flying recce aircraft with photographic equipment would have hard time telling the difference between the dummies and the real thing. The decoy airfields and dummy aircraft served several purposes simultaneously. They confused snooping enemy aircraft and hence planners as to the number of aircraft available to the opposing forces as well as to their displacement. They provided decoy targets for enemy bombers which, if attacked would prevent real aircraft from being destroyed. Often, these airfields were built near real airports in the path of attacking aircraft in the hopes that they would then drop their bombs and strafe the dummies, thereby saving the real aircraft.

H/T to Roger Henry for the original link.