For progressives, a legal minimum wage had the useful property of sorting the unfit, who would lose their jobs, from the deserving workers, who would retain their jobs. Royal Meeker, a Princeton economist who served as Woodrow Wilson’s U.S. Commissioner of Labor, opposed a proposal to subsidize the wages of poor workers for this reason. Meeker preferred a wage floor because it would disemploy unfit workers and thereby enable their culling from the work force.

Thomas Leonard, “Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2005-09.

February 6, 2018

QotD: The original goal of the minimum wage

January 28, 2018

The origins of the minimum wage

In Ontario, many businesses are still struggling to cope with the provincial government’s mandated rise in the minimum wage (the Tim Horton’s franchisees being the current Emmanuel Goldsteins as far as organized labour is concerned). In this essay for the Foundation for Economic Education, Pierre-Guy Veer points out that most franchise businesses have very low profit margins (2.4% for McDonalds franchises, for example) meaning that they can’t just pay the higher wages without a problem, and that the original intent of minimum wage legislation in the US was actually to drive down employment for certain ethnic and racial groups:

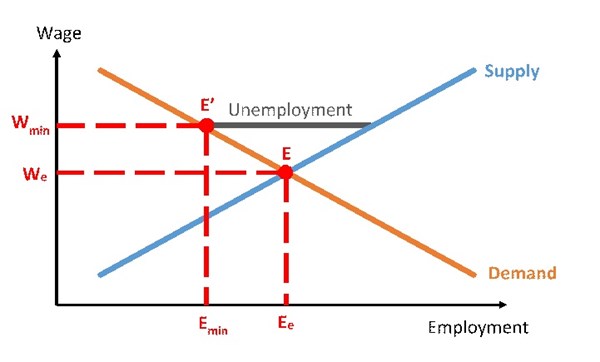

Normally, wages are determined at the intersection of supply (employees offering their services, the blue line) and demand (employers wanting workers, the orange line), the letter E. Since working in retail or restaurants requires little more than a high school diploma, that equilibrium is much lower than, say, a heart surgeon, who must endure years of training and study.

But when governments come and impose a minimum wage (the dark line), wages do increase… at the expense of workers. With a base wage now at E’, more workers want to work but fewer employers want to hire because of the increased cost. The newly formed triangle is made of surplus workers, i.e. unemployed workers who can’t find a job. This unlucky Brian meme summarizes the situation of what minimum wage is: wage eugenics.

And don’t think it’s a vice; creating unemployment was the explicit goal of imposing a minimum wage. It was a Machiavellian scheme imagined during the so-called Progressive Era (late 19th Century to about the 1920s), where it was thought that governments could better humanity by “weeding out” undesirables – in other words, eugenics.

In the U.S., this eugenic attitude was explicitly aimed at African Americans, whose (generally) lower productivity gave them lower wages. To “fight” this problem nationwide, the Hoover administration passed, in 1931, the Davis-Bacon Act in order to impose “prevailing wage” (usually unionized) on all federal contracts. It was a thinly veiled attempt to “weed out” non-unionized workers, who were either African American or immigrant, in order to protect unionized, white jobs. Supporters of the bill, like Representative Clayton Algood, were very explicit in their racist intents:

That contractor has cheap colored labor that he transports, and he puts them in cabins, and it is labor of that sort that is in competition with white labor throughout the country.

But while the racist intent of the minimum wage has disappeared, its effect is always very real. It greatly affects the people it wants to help, i.e. low-skilled workers, and leaves them with fewer options. So don’t be fooled by unemployment statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Youth participation rates (ages 16-19) are still hovering around all-time lows (affected, among others, by minimum wage laws); this means that fewer of them are looking for jobs, decreasing unemployment figures.

It gets worse when breaking down races; only 28.8 percent of African American youth were working or looking for a job, compared to 31.6 for Hispanics and 36.7 percent for whites in December 2017.

January 23, 2018

The unintended consequences of Ontario’s steep minimum wage hike

Colby Cosh on the unpredictable outcomes of Ontario’s recent minimum wage increase:

In Thursday’s edition of this paper, Marni Soupcoff wrote an entertaining column about how Ontario’s fairly aggressive minimum wage increase had suddenly raised the costs of labour-intensive goods and services for consumers — the ones, that is, who don’t benefit themselves from a minimum wage increase. Child care, which is a very pure purchase of labour, is the example that is being exasperatedly discussed this week. The headline did not have “duh” in it, but that was the spirit of the thing.

Soupcoff pointed out that this not only could have been foreseen; an explicit warning of it was given in the pages of the Toronto Star, by the paper’s social justice reporter Laurie Monsebraaten. Our Financial Post section could perhaps easily be called the Social Injustice Gazette, but anyone at FP who got such an early jump on an economics story would be rightly pleased with himself.

Soupcoff’s major point was that the broad-sense law of supply and demand is not some plutocratic swindle devised by the Monopoly Man and his fatcat pals; even believers in “social justice” have to take it into account, as they take gravity into account when they are moving an old couch to a charity shop or sending cosmonauts into orbit. This is obviously right as far as it goes, but the words “supply and demand” are not enough, on their own, to predict the precise market response to a change in a price control — which is what the minimum wage is.

That, perhaps, is the true key point amidst all the various ideological struggles currently in progress over minimum wage levels, which are being yoinked upward in Alberta as well as in Ontario. A minimum wage is a price control. The minimum wage is not really so much a labour standard as it is the abolition of labour bargains that feature a nominal wage below the minimum. And price controls are a blunt instrument. Most economists, whatever their political orientation, instinctively resist them.

The incidence of a price control — the precise place upon which the economic burden of it falls — is not, in fact, foreseeable without other information. In the market for hired child care, for example, it could turn out, with time, that the real effect of increasing a minimum wage is that some parents drop out of the labour market and tend to their own children. It’s just not what one would actually predict, because the need for professional child care is something that a family tends to plan for well in advance, with a longer time horizon than any government’s. (Also, we haven’t invented dependable babysitting robots yet.)

Women, in particular, organize lives and careers around whether they expect their own labour force participation to be able to cover care expenses. Indeed, couples adjust family size for these expectations. We can even imagine circumstances in which a province’s extreme, credible commitment to a very high future minimum wage influenced birth rates.

December 18, 2017

QotD: The perils of well-meaning regulation

Because the rich and powerful run the government, the poor and other powerless have been regularly hurt by governmental regulation – even by such sweet-sounding regulations as evening closing of shops (making it hard for the working poor to have time to shop) or protections limiting the hours women could work (making it hard for them to hold supervisory jobs requiring one to come early and stay late) or building codes claiming to promote safety but instigated by building trade unions (making it hard to build inexpensive housing) or minimum wages (making it hard for blacks, immigrants, women, and nonmembers of craft unions to get paying jobs).

Dierdre McCloskey, Bourgeois Equality, 2016.

September 30, 2017

Kathleen Wynne’s “War on Economics” is going great!

Giving people “free” stuff will always get you support from people who don’t understand TANSTAAFL (including the leader of the opposition), as Chris Selley explains:

Polls suggest Premier Kathleen Wynne’s ongoing war on economists is paying dividends. Fifty-three per cent approve of her Liberal government extending rent control to units built after 1991, according to a Forum Research poll conducted in May; only 25 per cent disapproved. In June, Forum found 53 per cent of Ontarians supported jacking up the minimum wage to $15 from $11.40 by Jan. 1, 2019, versus 38 per cent opposed. The move was hugely popular among Liberal voters (79 per cent) and NDP voters (28 per cent). Wynne’s approval rating is staggering back up toward, um, 20 per cent. But a Campaign Research poll released Sept. 13 had the Tories just five points ahead of the Liberals. That’s pretty great news for this beleaguered tribe.

The boffins still aren’t playing along, though.

Earlier this month, Queen’s Park’s Financial Accountability Office projected the hike would “result in a loss of approximately 50,000 jobs … with job losses concentrated among teens, young adults, and recent immigrants.” And it could be higher, the FAO cautioned, because there’s very little precedent for, and thus little evidence on which to judge, a hike as rapid as the one the Liberals propose — 32 per cent per cent in less than two years.

This week, TD Economics weighed in with a higher number: “a net reduction in jobs of about 80,000 to 90,000 positions by the end of the decade.” And the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis paints the grimmest picture: “We (expect) that the Act will, over two years, put 185,000 jobs at risk” — that’s jobs that already exist or that would otherwise have been created.

It’s easy to see why raising the minimum wage is popular. Governments like it because it doesn’t show up in the budget. We in the media can pretty easily find victims of an $11.40 minimum wage, and reasonably compassionate people quite rightly sympathize. Forty hours a week at $11.40 an hour for 50 weeks a year is $22,800. You can’t live on that.

Of course, these Liberal policies are flying in the face of mainstream economic theory, so you’d expect the Ontario Progressive Conservatives to have lots of arrows in the quiver to fight … oh, wait. Tory leader Patrick “I’m really a Liberal” Brown supports both the rent control and the minimum wage hike, just not quite as much at Wynne does. There’s Canadian “conservatism” in a nutshell for you: we also want to get on the express to Venezuelan economic conditions, just not quite as fast as the government wants. There’s a reason Kathleen Wynne isn’t as worried about getting re-elected as she used to be…

September 9, 2017

Minimum Wage: Bad for Humans, Good for Robots

Published on 7 Sep 2017

Jacking up the minimum wage sounds like a good idea, but it comes with disastrous consequences: low-skilled workers getting canned, employers cutting hours, and, of course, robots.

July 2, 2017

Minneapolis is going Seattle one better … and the results will be even worse

Tim Worstall explains why, despite all the pious hopes that significant increases in the minimum wage won’t negatively impact employment or take-home pay, Minneapolis will have measurably worse outcomes:

Minneapolis has just passed an ordinance making the minimum wage in that fine city $15 an hour at some point in the near future — the effects of this will be worse than the effects of the similar Seattle ordinance raising the minimum wage there to $15 an hour. I agree that this is an unpopular prediction but it’s one that I’ll still stick with for the interesting bit is that I predicted the effect of the Seattle rise correctly. I even managed to get right why it would go bad. This is not, sadly, because I have a crystal ball, nor am endowed with super-powers, it’s just that I understand the basic economics of the minimum wage.

The details of which are that modest rises in the minimum wage don’t have much effect. They don’t have much effect on wages and thus they don’t have much effect upon employment. Changes which are at best “Meh, marginal” have effects which are at best “Meh, marginal.” The problem with Seattle’s minimum wage rise was that it wasn’t marginal, the problem with that in Minneapolis is that it is even less so.

[…]

But why isn’t it all going to be wondrous? If we just insist that poor people should be paid higher wages then why won’t it all become copacetic? Well, this was tried in Seattle. And the results weren’t that way. We have the actual academic study of why and it’s just as conventional economics predicts. Modest rises in the minimum wage have modest effects, immodest rises have immodest. Which leaves us with trying to define immodest.

As I’ve been saying for some yeare now that definition of immodest seems to be 45 to 50 % of median wage in that labour market. We don’t usually have median wages by city, only by a rather larger economic unit. But Seattle’s area median is higher than that of Minneapolis. When we look at the cities, the mean is higher in Seattle than in Minneapolis.

We already know that $15 an hour is too high a minimum wage for Seattle, it leads to lower incomes for low wage workers. The Minneapolis $15 an hour minimum wage is higher compared to local wages–the effects will be worse.

June 27, 2017

Seattle sees some negative effects from their latest minimum wage hike

Ben Casselman and Kathryn Casteel report for FiveThirtyEight on initial reports from Seattle after their most recent increase in the city’s minimum wage rules:

In January 2016, Seattle’s minimum wage jumped from $11 an hour to $13 for large employers, the second big increase in less than a year. New research released Monday by a team of economists at the University of Washington suggests the wage hike may have come at a significant cost: The increase led to steep declines in employment for low-wage workers, and a drop in hours for those who kept their jobs. Crucially, the negative impact of lost jobs and hours more than offset the benefits of higher wages — on average, low-wage workers earned $125 per month less because of the higher wage, a small but significant decline.

“The goal of this policy was to deliver higher incomes to people who were struggling to make ends meet in the city,” said Jacob Vigdor, a University of Washington economist who was one of the study’s authors. “You’ve got to watch out because at some point you run the risk of harming the people you set out to help.”

The paper’s findings are preliminary and have not yet been subjected to peer review. And the authors stressed that even if their results hold up, their research leaves important questions unanswered, particularly about how the minimum wage has affected individual workers and businesses. The paper does not, for example, address whether displaced workers might have found jobs in other cities or with companies such as Uber that are not included in their data.

Still, despite such caveats, the new research is likely to have big political implications at a time when the minimum wage has returned to the center of the economic policy debate. In recent years, cities and states across the country have passed laws and ordinances that will push their minimum wages as high as $15 over the next several years. During last year’s presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton called for the federal minimum wage to be raised to $12, and she faced pressure from activists to propose $15 instead. (The federal minimum wage is now $7.25 an hour.) Recently, however, the minimum-wage movement has faced backlash from conservatives, with legislatures in some states moving to block cities from increasing their local minimums.

May 16, 2017

How service companies might respond to a mandated increase in the minimum wage

At Coyote Blog, Warren Meyer discusses how real world service companies that employ a lot of minimum wage workers are likely to respond when the minimum wage is raised:

When I discuss this with folks, they will say that the increase could still come out of profitability — a 5% margin could be reduced to 3% say. When I get comments like this, it makes me realize that people don’t understand the basic economics of a service firm, so a concrete example should help. Imagine a service business that relies mainly on minimum wage employees in which wages and other labor related costs (payroll taxes, workers compensation, etc) constitute about 50% of the company’s revenues. Imagine another 45% of company revenues going towards covering fixed costs, leaving 5% of revenues as profit. This is a very typical cost breakdown, and in fact is close to that of my own business. The 5% profit margin is likely the minimum required to support capital spending and to keep the owners of the company interested in retaining their investment in this business.

Now, imagine that the required minimum wage rises from $10 to $15 (exactly the increase we are in the middle of in California). This will, all things equal, increase our example company’s total wage bill by 50%. With the higher minimum wage, the company will be paying not 50% but 75% of its revenues to wages. Fixed costs will still be 45% of revenues, so now profits have shifted from 5% of revenues to a loss of 20% of revenues. This is why I tell folks the math of absorbing the wage increase in profits is often not even close. Even if the company were to choose to become a non-profit charity outfit and work for no profit, barely a fifth of this minimum wage increase in this case could be absorbed. Something else has to give — it is simply math.

The absolute best case scenario for the business is that it can raise its prices 25% without any loss in volume. With this price increase, it will return to the same, minimum acceptable profit it was making before the regulation changed (profit in this case in absolute dollars — the actual profit margin will be lowered to 4%). But note that this is a huge price increase. It is likely that some customers will stop buying, or buy less, at the new higher prices. If we assume the company loses 1% of unit volume for every 2% price increase, we find that the company now will have to raise prices 36% to stay even both of the minimum wage increase and lost volume. Under this scenario, the company would lose 18% of its unit sales and is assumed to reduce employee hours by the same amount. In the short term, just for the company to survive, this minimum wage increase leads to a substantial price increase and a layoff of nearly 20% of the workers. Of course, in real life there are other choices. For example, rather than raise prices this much, companies may execute stealth price increases by laying off workers and reducing service levels for the same price (e.g. cleaning the bathroom less frequently in a restaurant). In the long-term, a 50% increase in wage rates will suddenly make a lot of labor-saving capital investments more viable, and companies will likely substitute capital for labor, reducing employment even further but keeping prices more stable for consumers.

As you can see, in our example we don’t need to know anything about bargaining power and the fairness of wages. Simple math tells us that the typical low-margin service business that employs low-skill workers is going to have to respond with a combination of price increases and job reductions.

May 11, 2017

Words & Numbers: The Minimum Wage Conspiracy

Published on 10 May 2017

This week, James & Antony tackle minimum wage laws and present some hard facts that might surprise a lot of people.

See the YouTube description for a long list of links related to this discussion.

May 9, 2017

QotD: Wage floors and rent ceilings

[Progressives] tend to favor policies such as New York City’s rent controls, and the new $15 minimum wage being gradually phased in in some western cities. I like to think of these policies as engines of meanness. They are constructed in such a way that they almost guarantee that Americans will become less polite to each other.

In New York City, landlords with rent controlled units know that the rent is being artificially held far below market, and thus that they would have no trouble finding new tenants if the existing tenant is unhappy. So then have no incentive to upgrade the quality of the apartment, or to quickly fix problems. They do have an incentive to discriminate against minorities that, on average, are more likely to become unemployed, and hence unable to pay the rent. Or young people, who might damage the unit with wild parties.

Wage floors present the same sort of problem as rent ceilings, except that now it’s the demanders who become meaner, not the supplier. Firms that demand labor in Los Angeles in the year 2020 will be able to treat their employees very poorly, and still find lots of people willing to work for $15/hour.

Scott Sumner, “How bad government policies make us meaner”, Library of Economics and Liberty, 2015-08-25.

January 13, 2017

QotD: Markets and politics

Markets adapt to political changes, and the hierarchy of values that distinguishes between an hour’s worth of warehouse management, an hour’s worth of composing poetry, an hour’s worth of brain surgery, and an hour’s worth of singing pop songs is not going to change because a politician says so, or because a group of politicians says so, or because 50 percent + 1 of the voters say so, or for any other reason. To think otherwise is the equivalent of flat-earth cosmology. In the long term, people’s needs and desires are what they are; in the short term, you can cause a great deal of chaos in the economy and you can give employers additional reasons to automate rote work. But you cannot make a fry-guy’s labor as valuable as a patent lawyer’s by simply passing a law.

This is not a matter of opinion — that is how the world actually works. One of the many corrosive effects of having a political apparatus and a political class dominated by lawyers is that the lawyerly conflation of opinion with reality becomes a ruling principle. Lawyers and high-school debaters (the groups are not alien to one another) operate in a world in which opinion is reality: If you convince the jury or the debate judges that your argument is superior, or if you can get them to believe that your position is the correct one, then you win, and the question of who wins is the most important one if you are, e.g., on trial for murder. But if you shot that guy you shot that guy, regardless of what the jury says — facts are facts. Galileo et al. were right (or closer to right) about the organization of the solar system than were Fra Hieronimus de Casalimaiori and the Aristotelians, and the fact that Galileo lost at trial didn’t change that.

Kevin D. Williamson, “Bernie Sanders’s Dark Age Economics”, National Review, 2015-05-27.

January 9, 2017

QotD: The wider effects of raising the minimum wage

When the minimum wage goes up, owners do not en masse shut down their restaurants or lay off their staff. What is more likely to happen is that prices will rise, sales will fall off somewhat, and owner profits will be somewhat reduced. People who were looking at opening a fast food or retail or low-wage manufacturing concern will run the numbers and decide that the potential profits can’t justify the risk of some operations. Some folks who have been in the business for a while will conclude that with reduced profits, it’s no longer worth putting their hours into the business, so they’ll close the business and retire or do something else. Businesses that were not very profitable with the earlier minimum wage will slip into the red, and they will miss their franchise payments or loan installments and be forced out of business. Many owners who stay in business will look to invest in labor saving technology that can reduce their headcount, like touch-screen ordering or soda stations that let you fill your own drinks.

These sorts of decisions take a while to make. They still add up, in the end, to deadweight loss — that is, along with a net transfer of money from owners and customers to employees, there will also simply be fewer employees in some businesses. The workers who are dropped have effectively gone from $9 an hour to $0 an hour. This hardly benefits those employees. Or the employee’s landlord, grocer, etc.

There are secondary effects beyond the employment market too. Proponents of a higher wage are claiming that this will boost the local economy by putting more money into the pockets of workers. This is the same sort of argument you frequently hear for the construction of massive new sports complexes. But of course, the money has to come from someone else’s pocket — the customer and the employer. What were those people doing with it? If the answer is “buying stuff from Amazon,” then maybe diverting more money to wages is a net gain for the Los Angeles economy. But if the answer is mostly “buying stuff produced in LA” — for example, paying rent, or buying services performed by low-wage workers — then this is like trying to get rich by picking your own pocket.

There’s no question that the wage increase will transfer money around within the economy — out of the pockets of commercial landlords, for example, and into the pockets of folks who own real estate in low-rent districts. But little evidence has so far been offered that any boost in local spending will cancel out the deadweight loss, much less exceed it.

Megan McArdle, “$15 Minimum Wage Will Hurt Workers”, Bloomberg View, 2015-05-20.

June 18, 2016

QotD: The origin of the push for a minimum wage

Few policies have origins as ugly as that of the minimum wage. “Progressive” intellectuals in the early 20th century supported the minimum wage because they believed it to be an effective policy detergent to help cleanse the gene pool of ‘undesirables.’ By pricing low-skilled, ‘undesirable’ workers out of jobs, ‘undesirables’ are less likely to successfully pro-create and to immigrate. The fact that the minimum wage, by pricing ‘undesirables’ out of work, thereby artificially raises the incomes of white workers was considered to be an added benefit of this social-engineering device.

The ethics of these early supporters of the minimum wage were despicable. But say this much for these racist, protectionist creeps: they understood economics better than do many people today (including some economists) who believe either that the law of demand is uniquely inoperative in the market for low-skilled workers or that the American market for low-skilled workers is monopsonized.* Each belief is as inexplicable as it is unsupportable.

* And monopsonization of the labor market is only a necessary condition for a minimum wage to not destroy employment opportunities for some workers; it is not a sufficient condition.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2016-06-01.

May 31, 2016

QotD: The minimum wage

In truth, there is only one way to regard a minimum wage law: it is compulsory unemployment, period. The law says: it is illegal, and therefore criminal, for anyone to hire anyone else below the level of X dollars an hour. This means, plainly and simply, that a large number of free and voluntary wage contracts are now outlawed and hence that there will be a large amount of unemployment. Remember that the minimum wage law provides no jobs; it only outlaws them; and outlawed jobs are the inevitable result.

Murray Rothbard, “Outlawing Jobs: The Minimum Wage”, 1998.