Ryan Reeves

Published on 2 Jul 2014The 100 Years War between France and England lasted more than 100 years and was not one war but many. We explore Henry V and other important kings, and finish by exploring Joan of Arc as the savior of France.

Ryan M. Reeves (PhD Cambridge) is Assistant Professor of Historical Theology at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/RyanMReevesWebsite: http://www.gordonconwell.edu/academic…

For the entire course on ‘Church History: Reformation to Modern’, see the playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

June 17, 2019

100 Years War

June 9, 2019

History of England – The Devastation of France – Extra History – #3

Extra Credits

Published on 8 Jun 2019From the end of the battle of Crecy, Edward charged on to besiege Calais (successfully), and then returned home. Right about then was when the Black Plague hit Europe head-on. But Edward carried on as king establishing order among his subjects, forming the Knights of the Garter. In France, John le Bel, son of Philip, had learned from the French defeats and was making small victories here and there…

In the middle ages, pillaging and murdering your way across Northern France was clearly considered an appropriate father-son bonding opportunity.

Thanks again to David Crowther for writing AND narrating this series! https://thehistoryofengland.co.uk/pod…

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

May 20, 2019

The Evolution Of Knightly Armour – 1066 – 1485

Metatron

Published on 16 May 2017A video full of details which took over 30 hours in the making. I hope you like it and you find the info in it useful 😀

Armour (spelled armor in the US) is a protective covering that is used to prevent damage from being inflicted to an object, individual, or vehicle by weapons or projectiles, usually during combat, or from damage caused by a potentially dangerous environment or action. The word “armour” began to appear in the Middle Ages as a derivative of Old French. It is dated from 1297 as a “mail, defensive covering worn in combat”. The word originates from the Old French armure, itself derived from the Latin armatura meaning “arms and/or equipment”, with the root armare meaning “arms or gear”.

Armour has been used throughout recorded history. It has been made from a variety of materials, beginning with rudimentary leather protection and evolving through mail and metal plate into today’s modern composites.

Significant factors in the development of armour include the economic and technological necessities of its production. For instance, plate armour first appeared in Medieval Europe when water-powered trip hammers made the formation of plates faster and cheaper.Well-known armour types in European history include the lorica hamata, lorica squamata, and lorica segmentata of the Roman legions, the mail hauberk of the early medieval age, and the full steel plate harness worn by later medieval and renaissance knights, and breast and back plates worn by heavy cavalry in several European countries until the first year of World War I (1914–15). The samurai warriors of feudal Japan utilised many types of armour for hundreds of years up to the 19th century.

Plate armour became cheaper than mail by the 15th century as it required less labour, labour that had become more expensive after the Black Death, though it did require larger furnaces to produce larger blooms. Mail continued to be used to protect those joints which could not be adequately protected by plate.

The small skull cap evolved into a bigger helmet, the bascinet. Several new forms of fully enclosed helmets were introduced in the late 14th century.By about 1400 the full plate armour had been developed in armouries of Lombardy. Heavy cavalry dominated the battlefield for centuries in part because of their armour.

Probably the most recognised style of armour in the World became the plate armour associated with the knights of the European Late Middle Ages.

May 1, 2019

QotD: Standardized measurements, feudalism, and revolution

The pint in eighteenth-century Paris was equivalent to 0.93 liters, whereas in Seine-en-Montane it was 1.99 liters and in Precy-sous-Thil, an astounding 3.33 liters. The aune, a measure of length used for cloth, varied depending on the material (the unit for silk, for instance, was smaller than that for linen) and across France there were at least seventeen different aunes. […]

Virtually everywhere in early modern Europe were endless micropolitics about how baskets might be adjusted through wear, bulging, tricks of weaving, moisture, the thickness of the rim, and so on. In some areas the local standards for the bushel and other units of measurement were kept in metallic form and placed in the care of a trusted official or else literally carved into the stone of a church or the town hall. Nor did it end there. How the grain was to be poured (from shoulder height, which packed it somewhat, or from waist height?), how damp it could be, whether the container could be shaken down, and finally, if and how it was to be leveled off when full were subjects of long and bitter controversy. […]

Thus far, this account of local measurement practices risks giving the impression that, although local conceptions of distance, area, volume, and so on were different from and more varied than the unitary abstract standards a state might favor, they were nevertheless aiming at objective accuracy. This impression would be false. […]

A good part of the politics of measurement sprang from what a contemporary economist might call the “stickiness” of feudal rents. Noble and clerical claimants often found it difficult to increase feudal dues directly; the levels set for various charges were the result of long struggle, and even a small increase above the customary level was viewed as a threatening breach of tradition. Adjusting the measure, however, represented a roundabout way of achieving the same end.

The local lord might, for example, lend grain to peasants in smaller baskets and insist on repayment in larger baskets. He might surreptitiously or even boldly enlarge the size of the grain sacks accepted for milling (a monopoly of the domain lord) and reduce the size of the sacks used for measuring out flour; he might also collect feudal dues in larger baskets and pay wages in kind in smaller baskets. While the formal custom governing feudal dues and wages would thus remain intact (requiring, for example, the same number of sacks of wheat from the harvest of a given holding), the actual transaction might increasingly favor the lord. The results of such fiddling were far from trivial. Kula estimates that the size of the bushel (boisseau) used to collect the main feudal rent (taille) increased by one-third between 1674 and 1716 as part of what was called the reaction feodale. […]

This sense of victimization [over changing units of measure] was evident in the cahiers of grievances prepared for the meeting of the Estates General just before the Revolution. […] In an unprecedented revolutionary context where an entirely new political system was being created from first principles, it was surely no great matter to legislate uniform weights and measures. As the revolutionary decree read “The centuries old dream of the masses of only one just measure has come true! The Revolution has given the people the meter!”

James C. Scott, Seeing Like A State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, 1998.

April 28, 2019

QotD: Innovations in taxation

The door-and-window tax established in France [in the 18th century] is a striking case in point. Its originator must have reasoned that the number of windows and doors in a dwelling was proportional to the dwelling’s size. Thus a tax assessor need not enter the house or measure it, but merely count the doors and windows.

As a simple, workable formula, it was a brilliant stroke, but it was not without consequences. Peasant dwellings were subsequently designed or renovated with the formula in mind so as to have as few openings as possible. While the fiscal losses could be recouped by raising the tax per opening, the long-term effects on the health of the population lasted for more than a century.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like A State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, 1998.

April 26, 2019

The ill-founded notion that rural peasants had a better life than the city-dwelling poor

Historical illiteracy — encouraged by totally unrealistic historical fiction and highly selective memories — places the lifestyle of farm workers, herders, and other rural people before the industrial era in almost a Disneyfied state of Arcadian paradise. This misunderstanding of reality fed many of the complaints about the terrible living conditions of the poor in industrial towns and cities up to almost living memory — which, to be fair, were terrible, by the standards of the upper and middle classes of the day. Marian L. Tupy provides a bit of evidence for the horrible poverty and miserable living conditions of the majority of Europeans living outside the major towns and cities:

In my last two pieces for CapX, I sketched out the miserable existence of our ancestors in the pre-industrial era. My focus was on life in the city, a task made easier by the fact that urban folk, thanks to higher literacy rates, have left us more detailed accounts of their lives.

This week I want to look at rural life, for that is where most people lived. At least theoretically, country folk could have enjoyed a better standard of living due to their “access to abundant commons – land, water, forests, livestock and robust systems of sharing and reciprocity,” which the anthropologist Jason Hickel praised in a recent article in The Guardian. In fact, the life of a peasant was, in some important aspects, worse than that of a city dweller.

[…]

An account of rural life in 16th century Lombardy found that “the peasants live on wheat … and it seems to us that we can disregard their other expenses because it is the shortage of wheat that induces the labourers to raise their claims; their expenses for clothing and other needs are practically non-existent”. In 15th century England, 80 per cent of private expenditure went on food. Of that amount, 20 per cent was spent on bread alone.

By comparison, by 2013 only 10 per cent of private expenditure in the United States was spent on food, a figure which is itself inflated by the amount Americans spend in restaurants. For health reasons, many Americans today eschew eating bread altogether.

What about food derived from water, forests and livestock? “In pre-industrial England,” Cipolla notes, “people were convinced that vegetables ‘ingender ylle humours and be oftetymes the cause of putrid fevers,’ melancholy and flatulence. As a consequence of these ideas there was little demand for fruit and vegetables and the population lived in a prescorbutic state”. For cultural reasons, most people also avoided fresh cow’s milk, which is an excellent source of protein. Instead, the well-off preferred to pay wet nurses to suckle milk directly from their breasts.

The diet on the continent was somewhat more varied, though peasants’ standard of living was, if anything, lower than that in England. According to a 17th century account of rural living in France: “As for the poore paisant, he fareth very hardly and feedeth most upon bread and fruits, but yet he may comfort himselfe with this, and though his fare be nothing so good as the ploughmans and poore artificers in England, yet it is much better than that of the villano [peasant] in Italy.”

The pursuit of sufficient calories to survive preoccupied the crushing majority of our ancestors, including, of course, women and children. In addition to employment as domestic servants, women produced marketable commodities, such as bread, pasta, woollen garments and socks. Miniatures going back to the 14th century show women employed in agriculture as well. As late as the 18th century, an Austrian physician wrote, “In many villages [of the Austrian Empire] the dung has to be carried on human backs up high mountains and the soil has to be scraped in a crouching position; this is the reason why most of the young people [men and women] are deformed and misshapen.”

April 17, 2019

Some good news in the aftermath of the Notre-Dame de Paris fire

Mark Steyn, who is not normally noted for his habit of bringing good news, actually has some good news to share as the authorities in Paris evaluate the damage to the cathedral after the fire of April 15th:

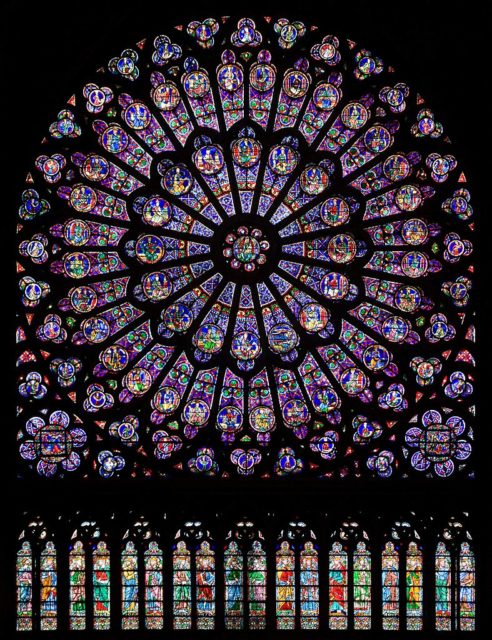

The north rose window of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, in a photo from 22 August, 2010. This and the other two rose windows are reported to have survived the fire of 15 April, 2019.

Photo by Julie Anne Workman. License: CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Twenty-four hours after Notre Dame de Paris began to burn, there is better news than we might have expected: More of the cathedral than appeared likely to has, in fact, survived intact – including the famous rose windows, among the most beautiful human creations I’ve ever seen. The “new” Notre Dame will be mostly high up and out of sight, which is just as well given that modern man prides himself on having no smidgeonette of empathy with his flawed forebears and thus the chances of historic recreation of the animating spirit of 1160 are near zero.

There is an architectural debate to be had, I suppose, about whether a reconstructed twelfth-century cathedral requires nineteeth-century appurtenances such as its spire. But the minute that starts you risk some insecure dweeb like Macron, on whose watch the thing went up in smoke, getting fanciful ideas about bequeathing to posterity some I M Pei pyramid on the top of the roof. France’s revolution, unlike America’s, was aggressively secular, and it ultimately found expression in the 1905 law on the separation of churches and the state. Since then the French state has owned the cathedral, and thus it will be Macron who ultimately decides what arises in its place.

Beyond that are the larger questions: When the iconic house of worship at the heart of French Christianity decides to mark Holy Week by going up in flames, it’s too obviously symbolic of something … but of what exactly? Two thousand churches have been vandalized in the last two years: Valérie Boyer, who represents Bouches-du-Rhône in the National Assembly, said earlier this month that “every day at least two churches are profaned” – by which she means arson, smashed statutes of Jesus and Mary, and protestors who leave human fecal matter in the shape of a cross. This is a fact of life in modern France.

As it is, there is no shortage of excitable young Mohammedans gleefully celebrating on social media. In 2017 some inept hammer-wielding nutter yelling “Allahu Akbar!” had a crack at Notre Dame, and a couple of years before that the historian Dominique Venner blew his brains out on the altar to protest same-sex marriage. I love France but, in recent years, it’s hard not to pick up on the sense that it’s coming apart – and that, when the center cannot hold, the things at that center, the obsolete embodiments of a once cohesive society, are a natural target.

In addition, the authorities’ eagerness to assure us that it was an accident at a time when such a conclusion could not possibly be known – and when their own response to the emergency was, to put it politely, somewhat dilatory – was itself enough to invite suspicion: “Sure, it might be an accident. But, even if it weren’t, they’d still tell us it was…”

So, precisely because Paris is full of people who would love to burn down Notre Dame four days before Good Friday, it seems bizarrely improbable that it should happen by accident: that a highly desirable target should be taken out by some slapdash workman leaving a cigarette butt near his combustible foam take-out box – the lunchpack of Notre Dame – and letting the dried-out twelfth-century timbers do the rest.

The Rose Window was spared! pic.twitter.com/D5NjepKzh3

— The French History Podcast (@FrenchHist) April 16, 2019

April 11, 2019

Modern History: A Funny Thing About Medieval Hoods

Modern History TV

Published on 7 Mar 2019A look at medieval hoods, how they’re used, how they’re worn and something you probably didn’t know about them.

Credits

Direction, Camera, Editing, Sound Kasumi

Presenter Jason Kingsley OBEMusic licensed from PremiumBeats

March 20, 2019

History Summarized: Medieval China (Ft Jack Rackam)

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published on 15 Mar 2019Check out our website at http://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Tale as old as time

Song as old as rhyme…

China broke agaiiinnnnnn — dammit china you only had one jobJack Rackam’s Channel: https://goo.gl/EgwpGu

PATREON: https://www.patreon.com/OSP

March 18, 2019

6 Worst British Rulers – Anglophenia Ep 8

Anglophenia

Published on 15 Jul 2014Britain has had a number of great kings and queens, but also some truly terrible ones. Siobhan Thompson looks at the worst of the worst.

QotD: The eternal bad bet that was feudalism

From time immemorial, the reigning myth of rule has been that the rulers provide a quid pro quo: in exchange for the people’s submission and payment of tribute, the rulers protect the people from the enemies who lurk “out there.” The promise was often unfulfilled, however. The lord of the manor might well flee into his castle, leaving the peasants outside the walls to suffer whatever outrages an invader chose to wreak on them. Or the lord might haul them off to a distant war in which they had no real interest, merely to satisfy the lord’s feudal obligation to the baron or duke just above him in the feudal pecking order.

Most important, however, is the sheer fact that the ordinary people’s most dangerous enemy, the one by far the most likely to plunder and abuse them, was their own impudent lord, the selfsame “nobleman” who forbade them to leave their place of birth or to engage in a variety of tasks and pleasures they might prefer — that is, the man who held and exploited them in a condition of serfdom.

Robert Higgs, “I Reject the Right of the Government to Choose My Friends and Enemies for Me”, The Beacon, 2017-04-03.

March 10, 2019

QotD: Surnames and taxes

… (related: Scott examined some of the same data about Holocaust survival rates as Eichmann In Jerusalem, but made them make a lot more sense: the greater the legibility of the state, the worse for the Jews. One reason Jewish survival in the Netherlands was so low was because the Netherlands had a very accurate census of how many Jews there were and where they lived; sometimes officials saved Jews by literally burning census records).

Centralized government projects promoting legibility have always been a two-steps-forward, one-step back sort of thing. The government very gradually expands its reach near the capital where its power is strongest, to peasants whom it knows will try to thwart it as soon as its back is turned, and then if its decrees survive it pushes outward toward the hinterlands.

Scott describes the spread of surnames. Peasants didn’t like permanent surnames. Their own system was quite reasonable for them: John the baker was John Baker, John the blacksmith was John Smith, John who lived under the hill was John Underhill, John who was really short was John Short. The same person might be John Smith and John Underhill in different contexts, where his status as a blacksmith or place of origin was more important.

But the government insisted on giving everyone a single permanent name, unique for the village, and tracking who was in the same family as whom. Resistance was intense:

What evidence we have suggests that second names of any kind became rare as distance from the state’s fiscal reach increased. Whereas one-third of the housholds in Florence declared a second name, the proportion dropped to one-fifth for secondary towns and to one-tenth in the countryside. It was not until the seventeenth century that family names crystallized in the most remote and poorest areas of Tuscany – the areas that would have had the least contact with officialdom. […]

State naming practices, like state mapping practices, were inevitably associated with taxes (labor, military service, grain, revenue) and hence aroused popular resistance. The great English peasant rising of 1381 (often called the Wat Tyler Rebellion) is attributed to an unprecedented decade of registration and assessments of poll taxes. For English as well as for Tuscan peasants, a census of all adult males could not but appear ominous, if not ruinous.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Seeing Like a State”, Slate Star Codex, 2017-03-16.

February 2, 2019

Did People in Medieval Times Really Wear Lockable Chastity Belts?

Today I Found Out

Published on 28 Mar 2016Never run out of things to say at the water cooler with TodayIFoundOut! Brand new videos 7 days a week!

In this video:

The lasting images of what most of us perceive to be the “medieval times” includes heroic knights, stampeding horses, court jesters, giant turkey legs, ruling kings, and pure maidens wearing chastity belts. But the fact is that, besides the more obvious of those that aren’t accurate, most scholars believe that the chastity belt didn’t actually exist during medieval times, but rather is a product of 18th and 19th century obsession with masturbation as a societal ill and safeguarding women in the workplace.

Want the text version?: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.p…

December 6, 2018

“Marx was right”

An interesting little bit of history and philosophy over at Rotten Chestnuts:

Marx was right: Society really is shaped by relations between the means of production.

The Middle Ages, for instance, organized itself around defense from marauding barbarian hordes. Fast, heavy cavalry were the apex of military technology at the time; the so-called “feudal” system were the cavalry’s support. The system was field tested in the later Roman empire — medieval titles like “duke” came from the ranks of the Roman posse comitatus — and perfected in the Dark Ages.

When the barbarians had been pacified sufficiently that Europeans had leisure time to think about this stuff, they took the feudal system — at that point a cumbersome relic — as their model for society. Hobbes, Locke, et al saw it as the origin of the Social Contract; Marx saw it as finely tuned oppression. But here’s the fun part:

Hobbes ends his Leviathan with the most absolute monarch that could ever be. He starts* with… wait for it… the equality of man. Marx, on the other hand, ends with the equality of man. He starts with a frank, indeed brutal, acknowledgment of man’s inequality. As much as I love Hobbes (and consider Leviathan the only political philosophy book worth reading), he’s wrong — fundamentally wrong — and Marx is right. Marx went wrong somewhere down the line; Hobbes jumped the track from page one.

Marx only went wrong when he started dabbling in metaphysics. Marxism isn’t the original underpants gnome philosophy, but it’s certainly the best — not least because Marx’s followers were so successful at hiding the deus ex machina that was supposed to bring Communism about. Marx didn’t just say “The Revolution will happen because that’s the way all the trend lines are pointing.” He said “the trend lines are pointing that way, and oh yeah, the animating Spirit of History demands that the Revolution shall happen.” This is so obviously sub-Hegelian junk that his followers dropped it as fast as they could, but to Marx himself it was the key to his philosophy. For all its formidable technobabble, Marxism is just another chiliastic mystery cult.

[…] Enlightenment-wise, Hobbes was the start, Marx the end of political philosophy, and both are flawed beyond redemption. Hobbes sure sounds like a viable alternative to Marx, because Hobbes’s reasoning seems sound, and based on an irrefutable premise: That in the State of Nature, life is nasty, poor, solitary, brutish, and short. But that’s not Hobbes’s premise — the fundamental equality of man in the State of Nature is. Life in the State of Nature is brutal because all men are equal.

* If you’ve read Leviathan, of course, you know he starts the book itself with a long discourse on contemporary physics. Hobbes was an innovator there, too — he’s the first person to put forth his humanistic ideas as the coldly logical deductions of physical science. It’d be fun to taunt the “I fucking love science” crowd with that, except they think Hobbes is a cuddly cartoon tiger and “Leviathan” one of the lesser houses at Hogwarts.

November 12, 2018

Viking Expansion – Ireland – Extra History – #3

Extra Credits

Published on 10 Nov 2018When Thorgest arrived on the coasts of Ireland with over a hundred long ships, he was ready to raid — and to establish cities like Dublin and many others that shaped the religion and culture of Ireland, much to the population’s excitement.

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon