Celebrity gossip is psychologically healthy.

It provides an outlet, a useful sublimation, of our self-destructive subconscious compulsion to lean over the back fence and cluck (or tweet) about the godawful things our relatives, friends, and neighbors do.

Celebrities are not our family. Although there are so many celebrities that we are probably related to some. But they’re not the niece looking daggers at us across the Thanksgiving turkey because of what we said to Uncle Bill about her hookup with that McDermott idiot. They’re not the daughter locked in her bedroom running up our Visa card bill with online shopping for new makeup, clothes, and other mall finds.

Celebrities are not our friends. They don’t borrow our money or power tools. They don’t forget it’s their turn to carpool the kids to junior high. They don’t come over when we’re busy watching The View and litter the kitchen table with used Kleenex, pouring their hearts out about their (remarkably frequent) divorces. They don’t get caught — unless Dean McDermott is late to the set for his televised therapy session on True Tori — necking with our spouses in the coat closet at our cocktail parties.

P.J. O’Rourke, “Welcome to Showbiz Sharia Law: No talent? Kind of dim-witted? No shame? Perfect. The celebrity industry needs you — just don’t ever veil your face”, The Daily Beast, 2014-05-04

December 22, 2014

QotD: Celebrity gossip as a common good

December 14, 2014

The New Republic was probably doomed anyway…

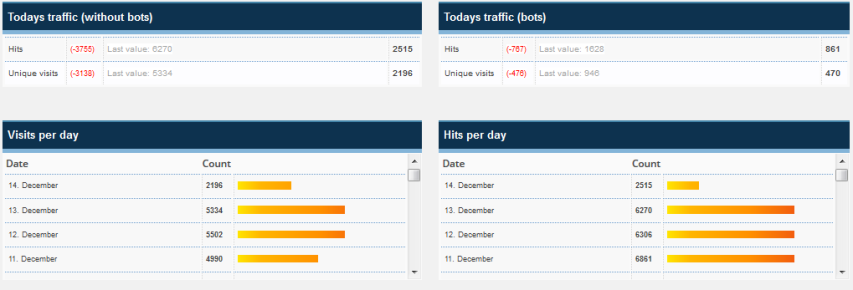

Let’s just say that there’s not a lot of profit for a monthly magazine with single-issue newsstand sales as low as this:

From a business standpoint, The New Republic was undoubtedly facing an uphill battle for profitability, even before last week’s events. According to the Pew Research Center and the Alliance for Audited Media, single copy sales of the magazine (considered the most objective measure of a magazine’s print appeal) have steadily declined over the past year, dropping to around 1,900 per issue.

They note that, between the first and second halves of 2013, newsstand sales fell by 57%, and fell a further 20% in the first of half of 2014.

One thousand, nine hundred readers. Per month.

Let me just give you a bit of perspective here:

At shortly after 10 a.m. on a quiet Sunday, I’ve already had more visitors to my obscure little personal blog today than there were copies of The New Republic sold in a recent month (not counting subscriptions).

That is not a viable business.

H/T to Kathy Shaidle, who also gets more daily traffic than TNR sells in a month.

December 8, 2014

Reason‘s Nick Gillespie and Matt Welch did an AMA at Reddit

The two Reason stalwarts did an “Ask Me Anything” session at Reddit last week:

Hello reddit.

We’re Matt Welch (/u/MattWelchReason) and Nick Gillespie (/u/Nick_Gillespie), the editors of Reason magazine, Reason.com and Reason TV and co-authors of 2011’s The Declaration of Independents: How Libertarian Politics Can Fix What’s Wrong With America.

Matt’s also the co-host of The Independents on Fox Business Network and Nick is a columnist for The Daily Beast and Time.com.

Go ahead and ask us anything about politics, culture, and ideas and the libertarian movement, 2016, you name it. But we’ve got to warn you that quite probably the toughest question — “Ever wonder what it’d look like if you switched faces?” — has already been asked and answered #triggerwarning

Proof: Matt and Nick

December 1, 2014

September 30, 2014

“…the outcomes of U.S. military intervention in Iraq and Libya disprove libertarianism”

Nick Gillespie responds to a really dumb argument against libertarianism:

As one of the folks (along with Matt Welch, natch), who started the whole “Libertarian Moment” meme way back in 2008, it’s been interesting to see all the ways in which folks on the right and left get into such a lather at the very notion of expanding freedom and choice in many (though sadly not all) aspects of human activity.

Indeed, the brain freeze can get so intense that it turns occasionally smart people into mental defectives.

To wit, Damon Linker’s recent essay in The Week (a great magazine, by the way), which argues that the outcomes of U.S. military intervention in Iraq and Libya disprove libertarianism, in particular, the Hayekian principle of “spontaneous order.”

No shit. Linker is being super-cereal here, kids:

Now it just so happens that within the past decade or so the United States has, in effect, run two experiments — one in Iraq, the other in Libya — to test whether the theory of spontaneous order works out as the libertarian tradition would predict.

In both cases, spontaneity brought the opposite of order. It produced anarchy and civil war, mass death and human suffering.

You got that? An archetypal effort in what Hayek would call “constructivism,” neocon hawks would call “nation building,” and what virtually all libertarians (well, me anyways) called a “non sequitur” in the war on terror that was doomed to failure from the moment of conception is proof positive that libertarianism is, in Linker’s eyes, “a particularly bad idea” whose “pernicious consequences” are plain to see.

In the sort of junior-high-school rhetorical move to which desperate debaters cling, Linker even plays a variation on the reductio ad Hitlerum in building case:

Some bad ideas inspire world-historical acts of evil. “The Jews are subhuman parasites that deserve to be exterminated” may be the worst idea ever conceived. Compared with such a grotesquely awful idea, other bad ideas may appear trivial. But that doesn’t mean we should ignore them and their pernicious consequences.

Into this category I would place the extraordinarily influential libertarian idea of “spontaneous order.”

What nuance: Exterminating Jews may be the worst idea…! When a person travels down such a rhetorical path, it’s best to back away quickly, with a wave of the hand and best wishes for the rest of his journey. Who can seriously engage somebody who starts a discussion by saying, “You’re not as bad as the Nazis, I’ll grant you that”…? I’d love to read his review of the recent Teenage Mutant Ninjas movie: “Not as bad as Triumph of the Will, but still a bad film…”

September 8, 2014

QotD: The Economist‘s whitewash of the “Great Leap Forward”

When Mao died, The Economist wrote:

“In the final reckoning, Mao must be accepted as one of history’s great achievers: for devising a peasant-centered revolutionary strategy which enabled China’s Communist Party to seize power, against Marx’s prescriptions, from bases in the countryside; for directing the transformation of China from a feudal society, wracked by war and bled by corruption, into a unified, egalitarian state where nobody starves; and for reviving national pride and confidence so that China could, in Mao’s words, ‘stand up’ among the great powers.” (emphasis mine)

The current estimate is that, during the Great Leap Forward, between thirty and forty million Chinese peasants starved to death. Critics questioning that figure have suggested that the number might have been as low as two and half million.

I am curious — has the Economist ever published an explicit apology or an explanation of how they got the facts so completely backwards, crediting the man responsible for what was probably the worst famine in history with creating a state “where nobody starves?” Is it known who wrote that passage, and has anyone ever asked him how he could have gotten the facts so terribly wrong?

David D. Friedman, “A Small Mistake”, Ideas, 2014-09-07.

July 13, 2014

July 3, 2014

Skeptical reading should be the rule for health news

We’ve all seen many examples of health news stories where the headline promised much more than the article delivered: this is why stories have headlines in the first place — to get you to read the rest of the article. This sometimes means the headline writer (except on blogs, the person writing the headline isn’t the person who wrote the story), knowing less of what went into writing the story, grabs a few key statements to come up with an appealing (or appalling) headline.

This is especially true with science and health reporting, where the writer may not be as fully informed on the subject and the headline writer almost certainly doesn’t have a scientific background. The correct way to read any kind of health report in the mainstream media is to read skeptically — and knowing a few things about how scientific research is (or should be) conducted will help you to determine whether a reported finding is worth paying attention to:

Does the article support its claims with scientific research?

Your first concern should be the research behind the news article. If an article touts a treatment or some aspect of your lifestyle that is supposed to prevent or cause a disease, but doesn’t give any information about the scientific research behind it, then treat it with a lot of caution. The same applies to research that has yet to be published.

Is the article based on a conference abstract?

Another area for caution is if the news article is based on a conference abstract. Research presented at conferences is often at a preliminary stage and usually hasn’t been scrutinised by experts in the field. Also, conference abstracts rarely provide full details about methods, making it difficult to judge how well the research was conducted. For these reasons, articles based on conference abstracts should be no cause for alarm. Don’t panic or rush off to your GP.

Was the research in humans?

Quite often, the ‘miracle cure’ in the headline turns out to have only been tested on cells in the laboratory or on animals. These stories are regularly accompanied by pictures of humans, which creates the illusion that the miracle cure came from human studies. Studies in cells and animals are crucial first steps and should not be undervalued. However, many drugs that show promising results in cells in laboratories don’t work in animals, and many drugs that show promising results in animals don’t work in humans. If you read a headline about a drug or food ‘curing’ rats, there is a chance it might cure humans in the future, but unfortunately a larger chance that it won’t. So there is no need to start eating large amounts of the ‘wonder food’ featured in the article.

How many people did the research study include?

In general, the larger a study the more you can trust its results. Small studies may miss important differences because they lack statistical “power”, and are also more susceptible to finding things (including things that are wrong) purely by chance.

[…]

Did the study have a control group?

There are many different types of studies appropriate for answering different types of questions. If the question being asked is about whether a treatment or exposure has an effect or not, then the study needs to have a control group. A control group allows the researchers to compare what happens to people who have the treatment/exposure with what happens to people who don’t. If the study doesn’t have a control group, then it’s difficult to attribute results to the treatment or exposure with any level of certainty.

Also, it’s important that the control group is as similar to the treated/exposed group as possible. The best way to achieve this is to randomly assign some people to be in the treated/exposed group and some people to be in the control group. This is what happens in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and is why RCTs are considered the ‘gold standard’ for testing the effects of treatments and exposures. So when reading about a drug, food or treatment that is supposed to have an effect, you want to look for evidence of a control group and, ideally, evidence that the study was an RCT. Without either, retain some healthy scepticism.

June 5, 2014

A visual history of pin-up magazines

A review of a new three-volume history of the girly magazine:

Taschen delivers as only Taschen can with Dian Hanson’s History of Pin-Up Magazines, a comprehensive three-volume boxed set chronicling seven decades in over 832 munificently illustrated pages, tipping the scales at nearly seven hardbound pounds. Although each volume is ram-packed with a bevy of sepia sweethearts, hand-tinted honeys, and Kodachrome cuties squeezed between dozens of lurid full-page vintage magazine covers, the accompanying text is so compelling that you’re apt to actually read these books too. And there’s a lot to learn about the history of pin-up magazines, more than you’d ever imagine, and this set leaves no stone unturned and no skirt unlifted. From the suggestive early illustrations of the post-Victorian era to the first bare breasts, the intriguing sources that fueled the fires of popular fetish trends, and the many ways in which publishers tried to legitimize the viewing of nude women while gingerly dancing around obscenity laws, we watch this breed of pulp morph and reinvent with fiction or humor, and later the marriage of crime and flesh. We see the influence on pin-up culture in the wake of the First World War and with the advent of World War II and the rise of patriotica. We follow the path of the bifurcated girl, to eugenics, the role of burlesque, and the legalization of pubic hair. We venture under-the-counter, witness the death of the digest and the pairing of highbrow literature and airbrushed beauties. Hanson even treats us to a peek into the lesser-known black men’s magazine genre, and the contributions made by erotic fiction and Hollywood movie studios.

June 1, 2014

Kevin Williamson provokes a reaction to his Laverne Cox hit piece

The National Review‘s Kevin Williamson went out of his way to be provocative in his article about transgendered actress Laverne Cox:

The world is abuzz with news that actor Laverne Cox has become the first transgender person to appear on the cover of Time magazine. If I understand the current state of the ever-shifting ethic and rhetoric of transgenderism, that is not quite true: Bradley Manning, whom we are expected now to call Chelsea, beat Cox to the punch by some time. Manning’s announcement of his intention to begin living his life as a woman and to undergo so-called sex-reassignment surgery came after Time’s story, but, given that we are expected to defer to all subjective experience in the matter of gender identity, it could not possibly be the case that Manning is a transgendered person today but was not at the time of the Time cover simply because Time was unaware of the fact, unless the issuance of a press release is now a critical step in the evolutionary process.

As I wrote at the time of the Manning announcement, Bradley Manning is not a woman. Neither is Laverne Cox.

Cox, a fine actor, has become a spokesman — no doubt he would object to the term — for trans people, whose characteristics may include a wide variety of self-conceptions and physical traits. Katie Couric famously asked him about whether he had undergone surgical alteration, and he rejected the question as invasive, though what counts as invasive when you are being interviewed by Katie Couric about features of your sexual identity is open to interpretation. Couric was roundly denounced for the question and for using “transgenders” as a noun, and God help her if she had misdeployed a pronoun, which is now considered practically a hate crime.

On cue, Tom Chivers responds:

For Williamson, the term “trans woman” is, of course, meaningless. He refers to Cox as “he” throughout his piece (despite a Clarksonesque but-you-can’t-say-that-these-days line about how “misdeploying” pronouns “is now considered practically a hate crime”) and says that our modern sensibilities of referring to trans people as their preferred gender is “sympathetic magic”, “treating delusion as fact”, “policing language on the theory that language mystically shapes reality”, like a “voodoo doll”. “Regardless of the question of whether he has had his genitals amputated, Cox is not a woman, but an effigy of a woman,” he says.

This, Williamson would no doubt claim, is the-emperor-has-no-clothes telling-it-like-it-is. “Sex is a biological reality,” he points out, unarguably. Indeed it is. No amount of surgery or hormone therapy will allow Cox to become pregnant, no terms of address will turn that stubborn Y chromosome into a second X. That is, indeed, a simple fact of human biology.

But who disagrees with that? No one. Williamson’s fearless truthsaying is, in fact, a fatuous statement of the obvious, dressed up as iconoclasm. Nobody in the world believes that calling Cox and other trans women “women”, using the pronouns “she” and “her”, will change anything biological; they know that she will not be able to have children, no matter what words we use. They do it out of respect, and sensitivity – what we used, in fact, to call politeness. If someone wishes to be addressed as X, then it is polite, usually, to do so. There may be times when other considerations apply: if someone insists on being referred to as “Doctor” and using that to give them unearned authority, say. But if someone wants to change their name, then we are happy to let them do so, and to address them by their chosen name, because it’s their business. I see no reason why changing one’s chosen pronouns should be any different.

Update. On the non-confrontational side, Elio Iannacci reports on Laverne Cox for Maclean’s:

The standout figure in all this flurry of activity, of course, is advocate/actress Laverne Cox, who graces the cover of this week’s issue of Time magazine. Cox is the breakout star of Netflix’s popular prison drama, Orange Is The New Black, which begins airing its second season next week.

Cox, an academic, writer and film producer as well as performer, has been fighting for Trans rights well before she had her first major guest spot on Law & Order and appeared in the reality show I Want To Work For Diddy in 2008. She says trans issues weren’t broached so intelligently five years ago. “I’m not naming names because I’m a working actress … but let’s get real,” she says via phone from New York City. “We’ve had such a wave of trans-ploitation films and TV — but that’s changing.” She is aggressively seeking to be a part of that change; she’s producing a documentary on transgender teens as well as one on Ce Ce MacDonald, an African-American trans woman who served a 41-month prison sentence in a men’s prison in Minnesota. “We are in the midst of a revolutionary moment,” she says.

Even a few years ago, the current profusion of trans characters and would have been unimaginable. A trans character was more likely an afterthought in a script, treated as a cliché or a freak. Most had more in common with Jared Leto’s trans character in Dallas Buyers Club, an Oscar-winning role that some critics have protested, saying it mirrors the offensive Mammy caricature in Gone With The Wind. On the fourth season of the popular reality series Project Runway, in 2008, fashion designer Christian Seriano used disparaging phrases such as “hot tranny mess” to describe inelegant or unstylish people. The word seeped into mainstream vernacular.

“We’ve had years of being at the end of the bad jokes and getting our bodies sensationalized,” says Cox, “but we have since learned to speak up. Transgender people in social media began standing up and saying, ‘This is not me and this is not acceptable.’ ”

April 25, 2014

Is it science or “science”? A cheat sheet

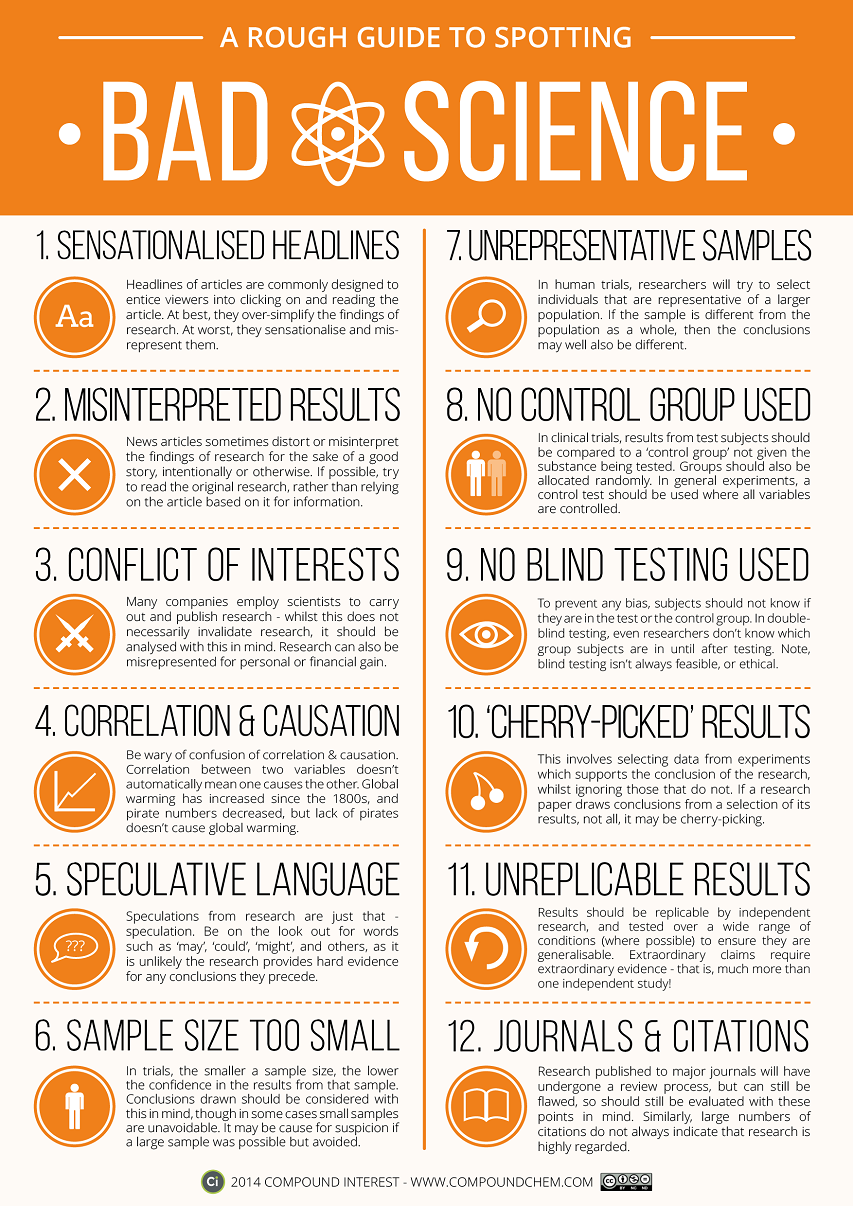

At Lifehacker, Alan Henry links to this useful infographic:

Science is amazing, but science reporting can be confusing at times and misleading at worst. The folks at Compound Interest put together this reference graphic that will help you pick out good articles from bad ones, and help you qualify the impact of the study you’re reading

One of the best and worst things about having a scientific background is being able to see when a science story is poorly reported, or a preliminary study published as if it were otherwise. One of the worst things about writing about science worrying you’ll fall into the same trap. It’s a constant struggle, because there are interesting takeaways even from preliminary studies and small sample sizes, but it’s important to qualify them as such so you don’t misrepresent the research. With this guide, you’ll be able to see when a study’s results are interesting food for thought that’s still developing, versus a relatively solid position that has consensus behind it.

April 4, 2014

Free Speech NOW!

sp!ked launches a new project:

Every man should think what he likes and say what he thinks.’ It is 350 years since Spinoza, the great Dutchman of the Enlightenment, wrote those simple but profound words. And yet every man (and woman) is still not at liberty to think what he or she likes, far less say it. It is for this reason that, today, spiked is kicking off a transatlantic liberty-loving online magazine and real-world campaign called Free Speech Now! — to put the case for unfettered freedom of thought and speech; to carry the Spinoza spirit into the modern age; to make the case anew for allowing everyone to say what he thinks, as honestly and frankly as he likes.

It is true that, unlike in Spinoza’s day, no one in the twenty-first century is dragged to ‘the scaffold’ and ‘put to death’ for saying out loud what lurks in his heart — at least not in the Western world. But right now, right here, in the apparently democratic West, people are being arrested, fined, shamed, censored, cut off, cast out of polite society, and even jailed for the supposed crime of thinking what they like and saying what they think. You might not be hanged by the neck anymore for speaking your mind, but you do risk being hung out to dry, by coppers, the courts, censorious Twittermobs and other self-elected guardians of the allegedly right way of thinking and correct way of speaking.

Ours is an age in which a pastor, in Sweden, can be sentenced to a month in jail for preaching to his own flock in his own church that homosexuality is a sin. In which British football fans can be arrested for referring to themselves as Yids. In which those who too stingingly criticise the Islamic ritual slaughter of animals can be convicted of committing a hate crime. In which Britain’s leading liberal writers and arts people can, sans shame, put their names to a letter calling for state regulation of the press, the very scourge their cultural forebears risked their heads fighting against. In which students in both Britain and America have become bizarrely ban-happy, censoring songs, newspapers and speakers that rile their minds. In which offence-taking has become the central organising principle of much of the political sphere, nurturing virtual gangs of the ostentatiously outraged who have successfully purged from public life articles, adverts and arguments that upset them — a modern-day version of what Spinoza called ‘quarrelsome mobs’, the ‘real disturbers of the peace’.

[…]

The lack of a serious, deep commitment to freedom of speech is generating new forms of intolerance. And not just religious intolerance of the blasphemous, though that undoubtedly still exists (adverts in Europe have been banned for upsetting Christians and books in Britain and America have been shelved for fear that they might offend Muslims). We also have new forms of secular intolerance, with governmental scientists calling for ‘gross intolerance’ of those who promote quackery and serious magazines proposing the imprisonment of those who ‘deny’ climate change. Just as you can’t yell fire in a crowded theatre, so you shouldn’t be free to ‘yell “balderdash” at 10,883 scientific journal articles a year, all saying the same thing’, said a hip online mag this week. In other words, thou shalt not blaspheme against the eco-gospel. Where once mankind struggled hard for the right to ridicule religious truths, now we must fight equally hard for the right to shout balderdash at climate-change theories, and any other modern orthodoxy that winds us up, makes us mad, or which we just don’t like the sound of.

March 27, 2014

The political divergent … who must be stopped

Nick Gillespie uses the current film Divergent as a springboard to discuss why Rand Paul’s “politically divergent” message is so unwelcome to the mainstream media who cheer for team red or team blue:

It turns out that Divergent isn’t just the top movie in America. It’s also playing out in the run-up to the 2016 presidential race, with Sen. Rand Paul, the Kentucky Republican, in the starring role.

Based on the first volume of a wildly popular young-adult trilogy, Divergent is set in America of the near-future, when all people are irrevocably slotted into one of five “factions” based on temperament and personality type. Those who refuse to go along with the program are marked as divergent — and marked for death! “What Makes You Different, Makes You Dangerous,” reads one of the story’s taglines.

Which pretty much sums up Rand Paul, whose libertarian-leaning politics are gaining adherents among the plurality of Americans fed up with bible-thumping, war-happy, budget-busting Republicans and promise-breaking, drone-dispatching, budget-busting Democrats. Professional cheerleaders for Team Red and Team Blue — also known as journalists — aren’t calling for Paul’s literal dispatching, but they are rushing to explain exactly why the opthalmologist has no future in politics.

A national politician who brings a Berkeley crowd to its feet by attacking NSA surveillance programs and wants to balance the budget yesterday? Who supports the Second Amendment and the Fourth Amendment (not to mention the First and the Tenth)? A Christian Republican who says that the GOP “in order to get bigger, will have to agree to disagree on social issues” and has signaled his willngness to get the federal government out of prohibiting gay marriage and marijuana?

Well, we can’t have that, can we? Forget that Paul is showing strongly in polls about the GOP presidential nomination in 2016. “He is not doing enough to build the political network necessary to mount a viable presidential campaign,” tut-tuts The New York Times, which seems to be breathing one long sigh of relief in its recent profile of Paul. “Rand Paul’s Plan to Save Ukraine is Completely Nuts,” avers amateur psychologist Jonathan Chait at New York.

March 7, 2014

Breaking news – Satoshi Nakamoto isn’t really “Satoshi Nakamoto”

Self-described Bitcoin detractor Colby Cosh explains how “Newsweek” got conned by “Satoshi Nakamoto” (yes, both sets of scare quotes are ‘splained):

Newsweek’s Satoshi is a 64-year-old Japanese-American living in Temple City, California. “Satoshi Nakamoto” is the name on his birth certificate, although he goes by Dorian. Mr. Nakamoto has a physics degree and has done computer engineering for a number of military-industrial firms, as well as one online stock-price provider. Much of his work history is shrouded in official secrecy, or perhaps just the habitual truculence of defence-tech professionals. He is known to have a libertarian streak, has had some run-ins with the financial system, and is thought by friends and relatives to capable of cooking up something like Bitcoin.

But it is now looking as though he had the square root of bugger-all to do with it. Newsweek concluded its investigation of Dorian S. Nakamoto with a police-supervised doorstep interview in which the gentleman is supposed to have said “I am no longer involved in that and I cannot discuss it. It’s been turned over to other people.” Dorian has now told the Associated Press that when he said “no longer,” two words on which Newsweek hung an entire feature, he was referring to the engineering profession generally. He denied being involved in any way with what he repeatedly called “Bitcom,” explained the work he had briefly done for a financial-information company, and read the Newsweek piece to himself, displaying increasing confusion and annoyance as he did so.

I have to say, having read New Newsweek’s article, that it does appear to rest on a fairly slender foundation. Aside from that “no longer,” the evidence that Dorian Satoshi Nakamoto equals “Satoshi Nakamoto” amounts to the obvious coincidence of names and a bunch of quotes from the man’s semi-estranged family. Unfortunately, neither “Satoshi” nor “Nakamoto” are uncommon names for individuals of Japanese ancestry; the article acknowledges that there are several more just in the United States. The Bitcoin-inventing “Satoshi” clearly does not much want to be found; the name is obviously a pseudonym, has always been taken to be one until now, and was probably chosen precisely for its red-herring flavour.

Okay, so Satoshi Nakamoto is probably not “Satoshi Nakamoto”, but why is Newsweek actually “Newsweek” in scare quotes?

A lot of people are asking how something like this could happen to Newsweek, not realizing that the Newsweek nameplate has basically been asset-stripped and repurposed in order that the remaining credibility and familiarity might be squeezed out of it. (This will happen to Maclean’s someday — two years from now, or 200. I’m hoping it’s 200.) No one expected this cred-squeezing process to happen quite so quickly and powerfully, but IBT Media, buyer of Newsweek, seems to have blundered into a singular piece of ill luck: the wrong reporter matched at the wrong time with the wrong story, one in which an informed intuition about any number of subjects might have saved the day.

February 15, 2014

HMS Love Boat, er, I mean HMS Daring

Sir Humphrey notes the tut-tutting disapproval of other military sites but defends the Royal Navy’s little Valentine Day squib:

To mark Valentines Day this year, the Royal Navy put out a small number of press releases showing how some deployed ships like HMS Daring had tried to mark the occasion. For instance, there was a picture of the crew on the flight deck, spelling out an ‘I love you’ message (news release is HERE). This particular story got quite a lot of media attention in the UK press, with a variety of outlets carrying it and giving coverage to the story. But, it also had its detractors — the superb website Think Defence did not appreciate the story, feeling that it perhaps didn’t reflect the RN in a truly professional manner — their views can be found HERE. The view expressed was essentially that in pushing across a human interest story, the RN was not demonstrating itself to be as professional as its peers in other navies, who perhaps did not feel the need to provide equivalent stories.

This debate perhaps goes to the heart of the question about how we can push the case for Defence in the modern UK. To the authors mind, the issue is that what specialists consider of interest, and what the wider public consider of interest is two very different, and often arguably mutually incompatible subjects. Wander into any UK major newsagent and you will come across rack after rack of deeply specialist magazines, often providing immensely technical commentary on the most niche of subjects, ranging from transportation through to outdoor model railways and agricultural vehicles (a favourite story of the author is of when serving in Iraq seeing a friend open a morale package to receive a magazine about tractors, whose review of the novel A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian complained that while a good read, it would have benefited from far more detail about the tractors). All of these magazines have one thing in common — they write technical articles for a technically minded audience which gets much of the underpinning issues. There are letters pages and articles full of debates on the most minor of points, quite literally arguing over the location of a decimal place or widget. There is an incredible passion and intensity to these debates, but the fact remains that the subject matter remains a deeply niche and specialist interest.

Arguably Defence is in a similar position to this — it is an organisation full of technical equipment, and engages in all manner of activities which people can take either an immensely superficial view, or spend many years becoming world class experts in. The problem is how to meet the interests of the experts, without losing the interest of the wider audience, who may have little to no idea of what the MOD really does all day. To an interested audience which inherently understands the importance of things like why the deployment of HMS Daring to the Far East was important, and why it achieved a tremendous amount of good for the RN, this sort of press release may well seem embarrassing — after all, who wants to see pictures of sailors missing their families when we could see press releases issued discussing whether there is sufficient space in the T45 hull to adopt a Mk141 launcher for VLS TLAM behind the PAAMS launcher but only if CEC were put onboard and the 114mm gun were downgraded to a 76mm OTO Melara — a complete exaggeration, but indicative of the sort of immensely technical debate which can be found in certain parts of the internet or specialist magazines.