I have banged on and on and on, to the annoyance of some of my readers, about how Pierre Elliot Trudeau reshaped Canada, almost entirely, in my considered opinion, for the worse. I have singled out, frequently, his evident distaste for the Canadian military and his very real isolationism and reluctance to have armed forces, at all.

There is a lot of documentation about Pierre Trudeau and his views and attitudes, much of it laudatory, some of it critical. I make no secret of the fact that I assert that one Canadian prime minister (perhaps, in my opinion, Canada best-ever leader) the great Liberal Louis St. Laurent, gave Canada a coherent, principled, liberal, values-based grand strategy in the late 1940s and then, just 20 years later another Liberal, Pierre Trudeau, tore it all down, threw it all aside and imposed new, very illiberal, values on Canada ~ all because, I guess, he could not reconcile the facts that stared him in the face in the late 1940s with his own personal choice to have stood, firmly, on the wrong side of history in 1944 when he elected to continue to study (this time at Harvard) rather than to join in the fight to crush Hitler.

M. St. Laurent and M. Trudeau could not have been more different. Louis St. Laurent was an internationally respected lawyer, he was “a man of the world”, neither an anglophile, like Sir Wildred Laurier, nor an anglophobe like Trudeau, he was secure in being a Canadian. He came to politics reluctantly, as a duty, but he quickly became known to, respected by, and, indeed, often friends with Harry Truman, George Marshal, Dwight Eisenhower and Dean Acheson, with Anthony Eden, Ernest Bevin, Clement Atlee, Sir Winston Churchill and Harold Macmillan, and with Tage Erlander of Sweden, Jawaharlal Nehru and V.K. Krishna Menon in India, Sir Robert Menzies of Australia, Tunku Abdul Rahman in Malaysia and leaders, from the West, the East and the non-aligned states. Pierre Trudeau, on the other hand, was a small, very parochial man who did not, really, understand Canada, beyond French-speaking Québec. He became “famous” for opposing Maurice Duplessis ~ something, I have suggested, that would not be much beyond the intellectual capabilities of a somnolent house cat. He travelled the world but never seemed, to me, to have acquired the respect that was accorded to Louis St. Laurent or Mike Pearson … except, perhaps from Fidel Castro.

Ted Campbell, “Pierre Trudeau’s legacy”, Ted Campbell’s Point of View, 2019-08-02.

August 6, 2023

QotD: Pierre Trudeau’s legacy

January 25, 2019

Putting the federal cabinet on a radical diet

Earlier this week, Ted Campbell suggested that one (of many) problems Justin Trudeau faces is the sheer size of his cabinet: there are limits to the number of people who can be successfully managed to achieve an organization’s goals by a single person. This is the reason most armies limit the size of their smallest tactical units to at most ten soldiers … much more than that, and the average leader is unable to maintain direct control without delegating sub-groups to subordinates. Running a federal government is a much more complicated task than running an infantry section. He begins by praising what he feels was the best cabinet in federal history:

A friend and regular interlocutor, reacting to a comment I made about a week ago, suggesting that the Trudeau cabinet is still too large, challenged me to look at the “ideal” cabinet. Now, it is certainly no secret that I think the “best” government Canada ever had, in modern times, say during the past century, was a Liberal one, led by Louis St Laurent. It was firmly grounded in liberal political philosophy that was shared, and broadly accepted, by most Canadians; the St Laurent cabinet was determined to govern for the people, for each person, not just to govern the people; it was economically bold but, at the same time, fiscally prudent; it believed, firmly, in a principled foreign policy and a strong enough military to give it the muscle it would need, from time to time; it advanced increasingly progressive social policies, step-by-step, but always in moderation; it was about as competent and as honest as almost any government was ever going to be … bearing in mind that governments are composed of men and women much like us.

This was the St Laurent cabinet:

There is some doubt about the date of this picture; one Government of Canada source says 1948 and another says 1953; the few familiar faces around the table, Douglas Abbott, Brooke Claxton, Brigadier Milton Gregg VC, C.D. Howe and Lester B. Pearson all served throughout that entire period. What is not in doubt is that the cabinet was much smaller than what we see today: fewer than 20 members. Today’s cabinet has over 35 members.

The problems of large cabinets are grounded in two realities: more and more complex issues, especially social issues, and more choices. Louis St. Laurent had between 245 and 265 MPs in the whole House of Commons and he governed with between 118 and 191 Liberal MPs on the government side. Justin Trudeau has a bigger problem: any modern majority government has 170+ members and Canadians are much better informed (or at least aware) of what government might do for (and to) them. He, like every prime minister before him, responds to the challenge by giving every group a voice. The outcome is a larger and larger cabinet. It’s not Justin Trudeau’s fault, it wasn’t Pierre Trudeau’s fault, either.

The correct answer, in my opinion, is a two tier cabinet: senior and junior ministers or an “inner” and “full” cabinet.

December 16, 2018

Mackenzie King at war

Ted Campbell remembers Canada’s Second World War Prime Minister:

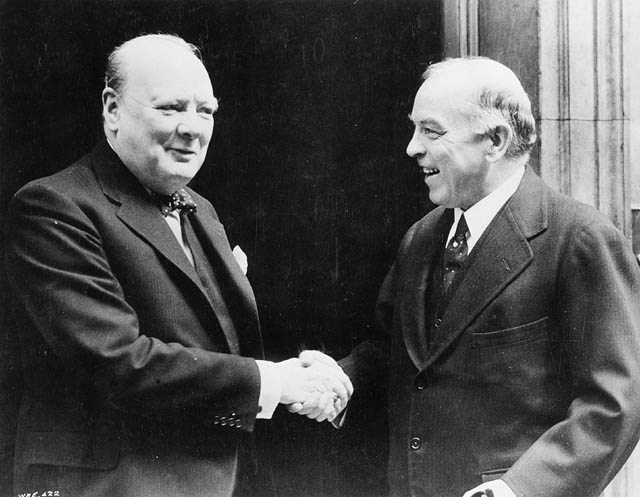

Prime Minister Winston Churchill greets Canadian PM William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1941.

Photo from Library and Archives Canada (reference number C-047565) via Wikimedia Commons.

I was born in 1942, William Lyon Mackenzie King was the prime minister; my mother often said that, in the 1940s, it seemed that he would never cease to be prime minister, and she thoroughly detested him; it wasn’t all of his policies she hated, it was, mainly, how he approached the war, and a few other things ~ she was, later, fond of the Canadian poet F.R. Scott’s rather bitter epitaph:

He seemed to be in the centre because we had no centre,

No vision to pierce the smoke-screen of his politics.Truly he will be remembered wherever men honour ingenuity,

Ambiguity, inactivity, and political longevity.Let us raise up a temple to the cult of mediocrity,

Do nothing by halves which can be done by quarters.Now, Canada fought a good war, we made four absolutely vital contributions:

- We were the true “breadbasket of the empire,” our farmers fed our large Army and much of Britain’s, too;

- We were a major part of the “arsenal of democracy,” our factories and shipyards turned out all of the things, from tanks and trucks and bombers and corvettes to Bren guns and grenades that were needed to help defeat the Axis powers;

- We managed the all important British Commonwealth Air Training Plan that was a key element in the allies’ eventual success; and

- We played a huge and a significant leadership role in the Battle of the Atlantic ~ the only battle Churchill said that he really feared losing.

But under King we did each with apparent reluctance, seemingly trying to never serve any vital interest if there was even a remote chance that any political constituency might be offended ~ something that reminds me of Justin Trudeau in 2018. Our large and entirely commendable war efforts were, in the main, directed, sometimes despite King, by the indefatigable C.D. Howe, and the national unity concerns were assuaged by recruiting the universally respected Louis St Laurent.

The King era was characterized by extraordinarily tepid leadership at the top but brilliant work by strong ministers in a small cabinet. It also began Phase 1 of a national political civil war. I think that in the First World War many Canadians had either understood or had been, largely, indifferent to Quebec’s objections to conscription. But in the 1940s we had better mass communications and many Canadians were less understanding of Quebec’s reluctance to participate in that war, especially as Canadian casualties mounted after Hong Kong and then in Italy and then in France, Belgium and Holland. Louis St Laurent did not try to explain French Quebec’s misgivings to English Canada, his job was to maintain, by force of his own stellar reputation and personality, just enough support in Quebec and, as he easily did, to “outclass” the vocal, crypto-fascist, French Canadian opponents to the war. But there was another division fomenting inside the Liberal Party of Canada: both Howe and St Laurent had a new vision for Canada in the post war world; both saw Canada as an important actor on the world stage; both were frustrated by King’s timid leadership; it is very probable that had St Laurent, the foreign minister, rather than King, [been] the prime minister, led Canada’s delegation to the UN’s founding conference in San Francisco in June of 1945 that Canada, not France, would have been the fifth member of the Security Council (or that it would have had only four members. as originally planned). St Laurent, especially, was known, liked and respected in both London and Washington; both he and Howe were highly regarded as leaders and as statesmen … King was not; Churchill distrusted him because he has actively supported Chamberlain’s appeasement policy and it seems to me that both Churchill and Roosevelt saw him as little more than an errand boy.