In Quillette, Bruce Bourque outlines some fascinating archaeological discoveries on Canada’s east coast and how the scientific findings are being actively blocked to avoid offending First Nations people for undermining or even contradicting their beliefs:

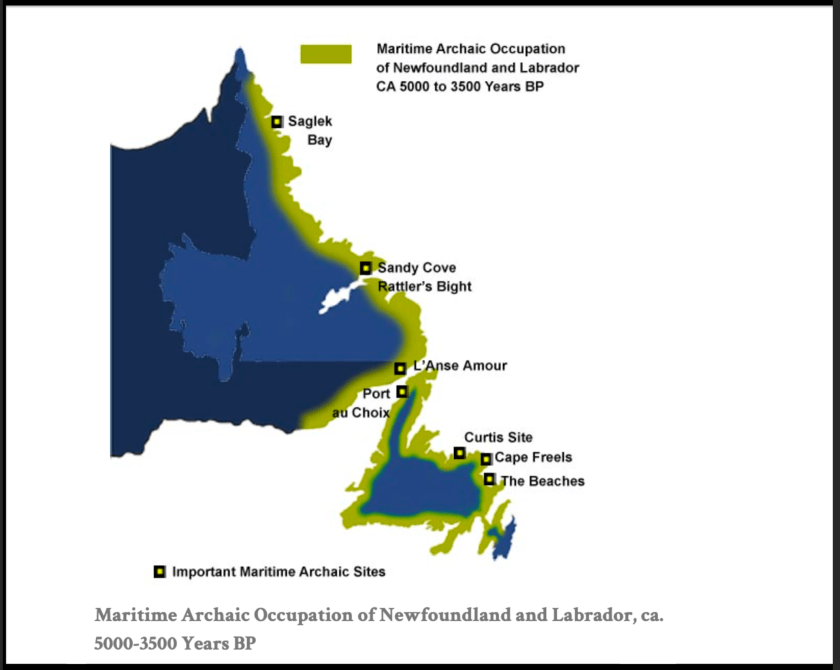

One of the major North American archaeological discoveries of the 20th century was made in 1967 by a bulldozer crew preparing a site for a movie theater in the small fishing village of Port au Choix (PAC), on Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula. It was a vast, 4,000-year-old cemetery created by a complex maritime culture known among researchers as the Maritime Archaic. The graves contained beautifully preserved skeletons covered in a brilliant red powder called red ocher (powdered specular hematite). Buried with the skeletons were many finely crafted artifacts. A few similar ones had previously turned up in earlier field surveys on the island, but no archaeologist had suspected that such a large and magnificent ceremonial site existed in the North American subarctic.

Had the discovery been made only a few years earlier, it is likely that no trained archaeologist would have taken over from the bulldozer crew. But fortunately, Memorial University in St. Johns had just added archaeologist James (“Jim”) Tuck (1940–2019) to its faculty. The American-born scholar set out to explore the cemetery, eventually excavating more than 150 graves spread over three clusters (which he referred to as loci).

[…]

In regard to the Red Paint People, Reich’s lab at Harvard Medical School analyzed material from the Nevin site in Blue Hill, Maine — the only known Red Paint cemetery that is likely ever to produce well-preserved human remains. Reich’s analysis was not confined to mDNA (which, unlike nuclear DNA, is transmitted through the maternal line, and so cannot address paternal ancestry), and focused instead on autosomal DNA (aDNA) found in cell nuclei, thereby adding information on the paternal line. (This addition can be critically important because, as Reich’s lab had demonstrated, a population can be founded by males and females with very different origins.) The Reich team has yet to publish comprehensive results of its Nevin site analysis. But from what I have heard, their work will confirm the existence of genetic discontinuities between the Red Paint People and later populations in the region, much as with Duggan’s work in regard to the Maritime Archaic.

But this is where events took a strange turn: It was when Duggan’s group announced that they’d gained the capacity to analyze aDNA, and made known their plans to apply this technology to the male genome of their Labrador/Newfoundland skeletal sample, that a sense of apprehension seemed to spread through some quarters of the paleogenetic community.

During the summer of 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests, Duggan’s project went noticeably quiet. I inquired among team members with whom I regularly communicated, but received oblique and evasive responses about the pace of research and publication. Suspecting that this might be related to sensitivities surrounding Indigenous populations (a topic that has consumed Canadian academia in recent years), I contacted Duggan directly, expressing concern that her valuable work might not be published.

[…]

When the Maritime Archaic tradition vanished, it was replaced, as noted earlier, by unrelated Paleoeskimos, an Arctic people who had then recently derived from Siberia. Following their own disappearance, more recently arrived inhabitants migrated from Labrador, these probably being ancestors of the historic Beothuk, who still lived in the region when Europeans arrived. The last surviving Beothuk, a woman named Shanawdithit, died of tuberculosis in 1829. And since that time, there has been no descendant Beothuk community with whom Duggan, or anyone else, could engage in the “discussions and agreements” she’d described to me.

And even if there were, moreover, Duggan’s own research has demonstrated that the Beothuk were not descended from the Maritime Archaic people of Port au Choix. The only community Duggan might be referring to is the (genealogically unrelated) Newfoundland Mi’kmaq community, whose ancestors arrived on Newfoundland from Nova Scotia in the 18th century, several hundred years after the arrival of Europeans.