Why, though, did Germans feel such a special affinity with “die Königin“? The most obvious reason is that the Royal Family is, to a great extent, of German extraction. The connections go back more than a thousand years to the Anglo-Saxons, but in modern times they begin with George I and the House of Hanover. This reverse takeover of the British monarchy by the Germans transformed the institution in countless ways. They may be summarised in four words: music, the military, the constitution and Christmas.

Music was a language that united the English and the Germans. The key figure was, of course, Handel — the first and pre-eminent but by no means the last Anglo-German composer. Born in Halle, Georg Friedrich Händel had briefly been George I’s Kapellmeister in Hanover yet had already established himself in England before the Prince Elector of Hanover inherited the British throne in 1714.

In London — then in the process of overtaking Paris and Amsterdam to become the commercial capital of Europe — he discovered hitherto undreamt-of possibilities. There he founded three opera companies, for which he supplied more than 40 operas, and adapted a baroque Italian art form, the oratorio, to suit English Protestant tastes.

His coronation music, such as the anthem, “Zadok the Priest”, imbued the Hanoverian dynasty with a new and splendid kind of sacral majesty. But he also added to its lustre by providing the musical accompaniment for new kinds of public entertainment, such as his Music for the Royal Fireworks: 12,000 people came to the first performance.

Along with music, the Germans brought a focus on military life. Whereas for the British Isles, the Civil War and the subsequent conflicts in Scotland and Ireland had been something of an aberration, war was second nature to German princes. Among them, George II was not unusual in leading his men into battle, although he was the last British monarch to do so.

Still, the legacy of such Teutonic martial prowess was visible in the late Queen’s obsequies: uniforms and decorations, pomp and circumstance, accompanied by funeral marches composed by a German, Ludwig van Beethoven. Ironically, the German state now avoids any public spectacle that could be construed as militaristic, yet most Germans harbour boundless admiration for the way that the British monarchy enlists the ceremonial genius of the armed services.

Even more important was the German contribution to the uniquely British creation of constitutional monarchy.

Each successive dynasty has left its mark on the monarchy’s evolution: from the Anglo-Saxons and Normans (the common law) to the Plantagenets (Magna Carta and Parliament) and Tudors (the Reformation). Only the Stuarts failed this test, at least until 1688. Even after the Glorious Revolution, the Bill of Rights and other laws that conferred statutory control over the royal prerogative, the constitutional settlement still hung in the balance when Queen Anne, the last Stuart ruler, died in 1714.

Coming from a region dominated by the theory and practice of absolute monarchy, the Hanoverians had no choice but to adapt immediately and seamlessly to the realities of politics in Britain, where their role was strictly limited. Robert Walpole and the long Whig ascendancy, during which the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty embedded itself irrevocably, could not have taken place without the acquiescence and active support of the new dynasty.

George III has been accused of attempting to reverse this process. The charge is unjust. Rather, as Andrew Roberts demonstrates in his new biography, he was “a monarch who understood his extensive rights and duties under the constitution”. He still had the right to refuse royal assent to parliamentary bills, but in half a century he never once exercised his veto (the last monarch to do so was the Stuart, Queen Anne in 1708).

At a time when enlightened despotism was de rigueur on the Continent, the Hanoverians were content to participate in an unprecedented constitutional experiment in their newly acquired United Kingdom. It was neither the first Brexit, nor the last, but it happened courtesy of a Royal Family that was still very German.

Daniel Johnson, “Why Germany mourned our Queen”, The Critic, 2022-10-30.

December 29, 2023

QotD: The Hanoverian “reverse takeover of the British monarchy by the Germans”

March 9, 2023

Look at Life – The Cherry Pickers (1965)

PauliosVids

Published 20 Nov 2018Following the 11th Hussars from Hanover to Coburg.

April 22, 2022

Lucy Worsely on The Jacobites & the Scottish Enlightenment

Whitehall Moll History Clips

Published 22 Jul 2018A segment on the Jacobites and the Scottish Enlightenment that blossomed in the face of Hanoverian oppression.

June 17, 2021

Encouraging innovation by … rejigging the honours system

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers how one man’s efforts to encourage and reward innovation in the United Kingdom eventually led to “mere inventors” receiving honours that once were dedicated to military paladins and political giants:

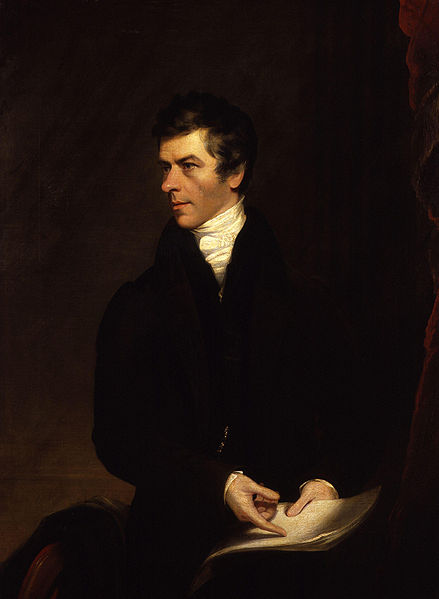

Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, by James Lonsdale (died 1839), given to the National Portrait Gallery, London in 1873.

Image from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

One of my all-time favourite innovation evangelists is the nineteenth-century barrister, journalist, and politician Henry Brougham. He was an innovator himself, in the late 1830s designing a form of horse-drawn carriage, and as a teenager even managed to get his experiments on light published in the Royal Society’s prestigious Transactions. But his main achievements were as an organiser. Clever, dashing, and articulate, the son of minor gentry, he was an evangelist extraordinaire. In the 1820s he helped George Birkbeck to found the London Mechanics’ Institute (which survives today as Birkbeck, University of London), was instrumental in the creation of University College London (to provide a university in England where you didn’t have to swear an oath to the Church of England), and founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (to print reference works and textbooks cheaply and in bulk). They were all organisations intended to widen access to education, spreading science to the masses.

He also presided at the opening of many more worker-run mechanics’ institutions, libraries, and scientific societies. As a Member of Parliament who went out of his way to support workers’ efforts at self-education, even though none of them could vote, Brougham thus became something of a celebrity to working-class inventors. John Condie, born in Gorbals, Glasgow, to poor parents, and apprenticed to a cabinet maker, would become a prolific and successful improver of iron-making, locomotive springs, and photography, as well as an inspiring lecturer on scientific subjects in his own right — his students at the Eaglesham Mechanics’ Institution were reportedly so engrossed that they would attend his evening classes until midnight. Having once exhibited a model steam engine at the opening of the Carlisle Mechanics’ Institution, however, Condie was reportedly “not a little proud” that Brougham — who had presided at the opening — recalled the model over thirty years later. The detail comes from Condie’s obituary notice in the local papers; I like to think that it was a story upon which he frequently dined out.

Brougham’s celebrity, I suspect, made him appreciate the usefulness of status and prestige, and his influence only grew when in 1830 he was made a lord and appointed Lord High Chancellor — a high-ranking ministerial position, which he held for four years. Brougham was soon behind many efforts to increase the visibility of inventive role-models. The nineteenth-century mania for putting up statues — to people like Johannes Gutenberg, Isaac Newton, and James Watt — often had Brougham or his political allies behind them. Brougham even hoped that while the “temples of the pagans had been adorned by statues of warriors, who had dealt desolation … ours shall be graced with the statues of those who have contributed to the triumph of humanity and science”.

His hero-making extended to print, too, when in the 1840s his Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge embarked on publishing a comprehensive biographical dictionary — an early forerunner to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, but with the extraordinary aim of covering notable individuals from all over the world. It managed to print seven volumes covering the letter “A” before financial considerations forced the whole society to cease, but in 1845 Brougham published Lives of Men of Letters and Science who Flourished in the Time of George III, in which he showcased a handful of eighteenth-century literati and scientists from whom readers were to draw inspiration.

And Brougham tried to raise the status of inventors who were still living. This was done by co-opting a Hanoverian order of chivalry, the Royal Guelphic Order (by this stage the kings of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland were also simultaneously the kings of Hanover). The order was generally used to recognise soldiers, but an interesting precedent had been set when the astronomer Frederick William Herschel, the discoverer of Uranus, had been made a knight of the order in 1816. So when Brougham rose to power in the 1830s, he envisaged using it more widely, to recognise inventors, scientists, and medical pioneers, as well as literary scholars like museum curators, archivists, antiquarians, historians, heralds, and linguists. Thanks to Brougham’s machinations, the knighthood of the order was offered to the mathematician James Ivory, the scientist and inventor David Brewster, and the neurologist Charles Bell (after whom Bell’s Palsy is named). It was later also awarded to serial inventors like John Robison, who improved the accuracy of metal screws, experimented with cast iron canal locks and the water resistance of boats, and applied pneumatic presses to cheesemaking.

One problem, however, was that the Royal Guelphic Order was considered second-rate. It was technically a foreign order, and did not actually entitle one to be called “Sir” in the UK. The mathematician and computing pioneer Charles Babbage was apparently insulted to have been fobbed off with the offer of a Guelphic knighthood instead of a British one. Although William Herschel had accidentally been called “Sir” during his lifetime, this was soon realised to be a mistake in protocol. When his son John — a scientific pioneer in his own right — was also made a knight of the order, he was also quietly knighted normally a few days later so that the rest of the family would be none the wiser. And regardless, the whole scheme came to an end with the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 — as a woman, she did not inherit the throne of Hanover, and so appointments to the Guelphic order simply passed out of British control.