It is an attractive idea to bring back the traditional counties of England. It is also an attractive idea to dig up the body of the man who abolished them, Edward Heath, and stick his head on a pike, but that won’t happen either. The counties are just too small.

So if we are to have petty kingdoms, let them at least be kingdoms. Men have loved the Kingdom of Mercia. Men have died for the Kingdom of East Anglia — notably at the hands of men of Mercia, but there you go. Men of all the ancient nations of the Saxon have followed the greatest of the Kings of Wessex to glorious victory against the Vikings. Divide and conquer that, Eurocrats! Also it would serve the Vikings right for subjecting me to all those irritating pictorial instructions.

Natalie Solent, “Restore the Heptarchy!”, Samizdata, 2014-09-20.

September 26, 2014

QotD: English regional governance

September 18, 2014

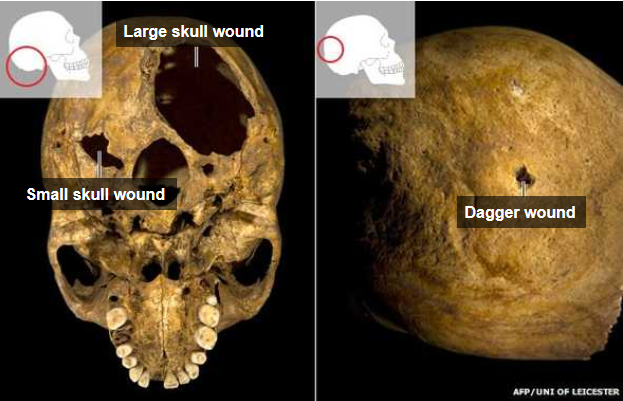

Forensic report on the death of Richard III

BBC News has the details:

Sarah Hainsworth, study author and professor of materials engineering, said: “Richard’s injuries represent a sustained attack or an attack by several assailants with weapons from the later medieval period.

“Wounds to the skull suggest he was not wearing a helmet, and the absence of defensive wounds on his arms and hands indicate he was still armoured at the time of his death.”

Guy Rutty, from the East Midlands pathology unit, said the two fatal injuries to the skull were likely to have been caused by a sword, a staff weapon such as halberd or bill, or the tip of an edged weapon.

He said: “Richard’s head injuries are consistent with some near-contemporary accounts of the battle, which suggest Richard abandoned his horse after it became stuck in a mire and was killed while fighting his enemies.”

September 15, 2014

BBC Last Night of the Proms 2014 – Jerusalem, God Save the Queen and Auld Lang Syne

August 25, 2014

Counting down to Scotland’s decision

While I’d prefer to see Scotland stay as part of the United Kingdom, lots of Scots would prefer to be independent of the UK. What I don’t understand is the idea that Scotland needs to be free, independent, and pleading and begging to be accepted into the EU. Isn’t that just trading distant uncaring bureaucrats in London for even more distant, even more uncaring bureaucrats in Brussels?

There are plenty of English cheerleaders for the “no” side, but there are also folks in England who’d prefer to see Scotland go off on its own:

In polite society, the correct opinion to hold about Scottish independence is that the Union must stay together. But I’ve been wondering: might not England thrive, freed from the yoke of those whining, kilted leeches? The more you think about it, the more persuasive the argument seems to be.

I’ve been invited to debate this question — whether or not we long-suffering Sassenachs would be better off without our sponging Caledonian neighbours — in early September, at a debate held by the Chartered Institute of Public Relations.

[…]

Let’s consider for a moment how Scotland herself might fare. In my view, she would be well served by some time alone to consider who she really is. Historically, Scotland was renowned across the world for entrepreneurial spirit and engineering genius. Both reputations have been lost after a century of Labour government and the overweening arrogance and control freakery of the trades unions.

These days, Scotland is more commonly associated with work-shy dole scroungers and skag-addled prostitutes than with the industriousness of Adam Smith or with its glorious pre-Reformation spirituality. Sorry, no offence, but it’s true.

[…]

Returning to England, then, let us imagine a Kingdom relieved of burdensome Scottish misanthropy. Surely it would experience an almost immediate burst of post-divorce gaiety. Think of our city centres, free of garrulous Glaswegian drunks slurping Buckfast tonic wine, or English literary festivals liberated from sour, spiky-haired Caledonian lesbians hawking grim thrillers about child abuse.

And here’s one last, even more delicious prospect: right-on Scottish stand-up comedians permanently banished to Edinburgh, where their ancient jokes about Thatcher or the Pope will make their equally ossified Stalinist audiences laugh so bitterly that Scotland’s famously dedicated healthcare workers will be left mopping up the leakage.

It makes you wonder whether we shouldn’t offer up Liverpool as well, to sweeten the deal. After all, the north of England is in a similarly bad state. What do you reckon of my modest proposal? Would a taste of the Calvinist lash persuade that feckless and conceited community to get off its behind and look for work? Why not let Holyrood underwrite their disability benefits bill for a while, and see what happens?

July 27, 2014

Al Stewart (finally) goes back to Bournemouth

A long time ago, in an English town most of you have never heard of…

He has achieved huge success as a singer-songwriter and has – by his own reckoning – made and lost a million dollars three times.

But although he long ago moved to California, Al Stewart remembers in vivid detail his life as a pop-obsessed teenager in Wimborne.

He will be back in the town on Friday, August 1, for a sold-out concert at the Tivoli – and to visit his old home at Canford Bottom.

“I got a very nice message from the person who now lives in the house I grew up in,” he told the Daily Echo from California.

“This lady invited me to look at my old bedroom.

[…]

After leaving school, Stewart went to work at Beales in Bournemouth – not in the record department, but in the linen department.

He also played guitar with The Tappers, who later backed a young Tony Blackburn as he attempted to become a pop star.

When Stewart joined Dave La Kaz and the G-Men, Jon presented the band to the Echo, claiming hyperbolically that the guitarist had written 40-50 songs.

Bournemouth’s music scene was thriving at the time.

Manfred Mann were a weekly attraction throughout 1963.

Stewart knew Andy Summers, later of the Police, and remembers sitting in Fortes coffee shop off Bournemouth Square with star-to-be Greg Lake and Lee Kerslake, who would later become drummer with Uriah Heep.

He took 10 guitar lessons from Robert Fripp.

But the biggest star of the local scene, he recalls, was Zoot Money, whose walk he would mimic behind the singer’s back.

In August 1963, The Beatles played six nights at the Gaumont cinema in Westover Road.

Not only were Al Stewart and Jon Kremer there on the first night, but afterwards, they contrived a ruse to meet the band. Stewart tells the story on stage, while Jon Kremer set it down in his memoir Bournemouth A Go! Go!

Wearing suits, the pair managed to get backstage by telling the manager that they were from the Rickenbacker guitar company.

Before long, they found themselves outside the band’s dressing room.

Having dropped the Rickenbacker pretence, they spent a few minutes chatting with John Lennon and trying his guitar.

“People tend to forget that we weren’t living in an age of mega-security,” Stewart recalled.

“You can’t just walk backstage and talk to Justin Timberlake. In those days it was very lax.”

Not directly related to the story, but one of my favourite arrangements of “Year of the Cat”, in a live performance from 1979:

July 16, 2014

QotD: Runnymede

We went over to Magna Charta Island, and had a look at the stone which stands in the cottage there and on which the great Charter is said to have been signed; though, as to whether it really was signed there, or, as some say, on the other bank at “Runningmede,” I decline to commit myself. As far as my own personal opinion goes, however, I am inclined to give weight to the popular island theory. Certainly, had I been one of the Barons, at the time, I should have strongly urged upon my comrades the advisability of our getting such a slippery customer as King John on to the island, where there was less chance of surprises and tricks.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the dog), 1889.

July 6, 2014

Henry II – “from the Devil he came, and to the Devil he will surely go”

Nicholas Vincent looks at the reign of King Henry II, the founder of the Plantagenet dynasty who died on this day in 1189:

Although in December 1154, Henry was generally recognised as the legitimate claimant to the throne, most notably by the English Church, his accession was fraught with perils. Among the Anglo-Norman aristocracy there were many who saw Henry as an outsider: an Angevin princeling, descended via his father, Count Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou, from a dynasty that had long been regarded as the principal rival on Normandy’s southern frontier. King Stephen had left a legitimate son, William Earl Warenne, still living in 1154, and Henry himself had two younger brothers who might well have disputed his claims to succeed to all his family’s lands and titles. Asked some years before to judge Henry’s chances of success, St Bernard of Clairvaux is said to have predicted of Henry that ‘from the Devil he came, and to the Devil he will surely go’.

Yet, from what contemporaries termed ‘the shipwreck’, and modern historians have described as ‘the anarchy’ of Stephen’s reign, Henry II was to emerge as one of England’s, indeed as one of Europe’s, greatest kings. The Plantagenet dynasty that he founded was to occupy the throne of England through to 1399 and the eighth successive generation. Henry himself came to rule over the most extensive collection of lands that had ever been gathered together under an English king – an empire in all but name, that stretched from the Cheviots to the Pyrenees, and from Dublin in the west to the frontiers of Flanders and Burgundy in the east.

In part this empire was the product of dynastic accident. From his mother, Matilda, daughter and sole surviving legitimate child of the last Anglo-Norman King, Henry inherited his claim to rule as king in England and as duke in Normandy. From his father, Geoffrey, he succeeded to rule over Anjou, Maine and the Touraine: the counties of the Loire valley that had previously blocked Anglo-Norman ambitions in the South. Rather than share these inherited spoils with his brothers, Henry seized everything for himself. William, his younger brother, was granted a rich but by no means royal estate. Geoffrey, the third brother, threatened rebellion but was bought off with a shortlived grant of the county of Nantes.

Henry, however, was far more than just a fortunate or crafty elder son. Through his own exertions he greatly expanded his family’s territorial claims. In 1152, two years before obtaining the throne of England, he had married Eleanor, heiress to the duchy of Aquitaine and only a few weeks earlier divorced from her previous husband, the Capetian King Louis VII. As effective ruler of Eleanor’s lands, Henry found himself in possession of a vast estate in south-western France, stretching from the Loire southwards through Poitou and Gascony to the frontiers of Spain. Henry’s marriage to Eleanor was regarded as scandalous even by his own courtiers. She was eleven years older than him and was rumoured to have enjoyed extra-marital affairs not only with her own uncle but with Henry’s father, Geoffrey Plantagenet. By temperament she was as fiery as Henry, and as determined to stake her own claims to rule. As a result, Henry’s domestic life was far from tranquil. From 1173 onwards, Eleanor was to be held under house arrest in England, whilst Henry, to judge by the bastard children that he fathered, had long enjoyed the favours of a series of mistresses. Even so, by his marriage, Henry laid the basis of the later claims made by England’s kings to rule over southern France: claims that were to unite Gascony to the English crown as late as the fifteenth century and which were to play a vital role in the history of Anglo-French relations throughout the Middle Ages and beyond.

June 23, 2014

World Cup sour grapes for England

While the England team may not need to worry about what to do in the elimination round (because they’re not going to get that far), James Delingpole claims that this is the greatest World Cup ever, and offers five reasons he’s right:

1. Filthy, cheating foreigners are conforming satisfyingly to stereotype.

The reason England are already out of the competition, claimed Wayne Rooney over the weekend, is that we are far too nice. If ever we wish to win again at the game we invented, he suggested, then we will have to learn to cheat like all the filthy foreigners with their effeminate hairstyles, their casual fouling and their extravagant diving.

But obviously we can’t do that sort of thing because then we’d look like the kind of people who still live with their mothers and eat garlic on toast and ride around piazzas on mopeds.

Which is why we prefer to lose because it shows our national superiority. Anyway, football is fixed now — so really it’s not up to the players who wins any more anyway, it’s decided by the betting syndicates in India and Pakistan and Ghana.

[…]

3. It has given the Scots something not to grumble about

Nothing — not a warming draught of deep fried Irn Bru (copyright Michael Deacon) nor the skirl of pipes nor the reassuring “pit” of the latest welfare cheque landing on the floor of your council flat — gladdens a Scotsman’s heart quite so much as the sight of England losing in a major (or indeed minor) sporting event.

It’s quite possible that, had England won this World Cup, the backlash would have driven the whole of Scotland into voting “Yes” in the forthcoming referendum. Those of us who love the Scots and dearly wish them to remain part of the Union, therefore, should rejoice in Britain’s tactical defeat in the World Cup.

[…]

5. Nazi Pope Reefer Man

Do I really need to explain?

My favourite Twitter post from the start of the World Cup now seems prescient:

The England team visited an orphanage in Brazil today. ‘It's heartbreaking to see their sad little faces with no hope,"’ said Jose, age 6.

— Peter Nurse (@PeterNurse1) June 11, 2014

June 20, 2014

The Black Death, the peasants’ revolt, and … tax increases

Put yourself in the position of an advisor to the 10-year old King Richard II shortly after his coronation in 1377. You’ve just witnessed one of the greatest population disasters in European history — the Black Death — where one third of the people of all classes died. The crown is at war with France (the Hundred Years’ War), and there’s little or no money in the treasury. You could probably come up with better policy ideas in your sleep than what Richard’s advisors did:

Fixated with outright victory in the One Hundred Years War, started by his grandfather Edward III, Richard’s government introduced hugely unpopular poll taxes in 1377 and 1379. A further tax introduced in 1381 was to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. Irrespective of wealth, the tax was fixed at a rate of 12 pence per person, meaning that it was a huge burden on the poor, but a minor inconvenience to the wealthy. In addition, rumours spread of widespread corruption in the government. The peasants were ripe for revolt.

Following the expulsion of a tax collector from the town Brentwood, 30 kilometres north-east of London, a band of rebels swept through Kent and Essex, swelling their numbers with volunteers as they went. They advanced upon London in a pincer movement from the south and east. The two leaders of the rebellion emerged as Wat Tyler, of whom little was previously known, and John Ball, a radical priest who had been broken out of prison by Kentish rebels, where he had been held for his beliefs in social equality and a fair distribution of wealth within the church. Indeed, as he preached to the crowd of thousands of rebels at Blackheath, then just outside London, he cried: ‘When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman? From the beginning all men by nature were created alike, and our bondage or servitude came in by the unjust oppression of naughty men.’

Londoners willingly opened the gates of their city to the rebels who set about their task with fervour. They sacked Savoy Palace, the home of the key adviser to the now 14-year-old Richard. Guards in the Tower of London opened the gates to the rebels, who freed the inmates and executed Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Treasurer of England, who had been hiding inside. There were also several incidents of misplaced rage among the rebels, like when the crowd set their sights upon Flemish immigrants, many of whom were wealthy wool merchants, and murdered them in the streets.

Faced with a grave situation, the young king rode out to meet the rebel leaders at Blackheath. Their demands were an end to poll taxes, an immediate end to serfdom, the introduction of a more democratic form of government with local representation based on the Provisions of Oxford in 1258, and a fair distribution of wealth and power from the nobility. Richard initially gave into their demands as well as issuing pardons for all involved.

It got worse (for the peasants) after that brief high point…

June 16, 2014

The tomb for Richard III

BBC News has images of the tomb designed for the re-burial of Richard III at Leicester Cathedral:

The design of the tomb King Richard III will be reburied in at Leicester Cathedral, has been unveiled.

The wooden coffin will be made by Michael Ibsen, a descendent of Richard III, while the tomb will be made of Swaledale fossil stone, quarried in North Yorkshire.

The total cost of reburial is £2.5m and work will start in the summer.

The Very Reverend David Monteith, Dean of Leicester, said the design “evokes memory and is deeply respectful”.

Judges ruled his remains, found under a Leicester car park in 2012, would be reinterred in Leicester, following a judicial review involving distant relatives of the king who wanted him buried in York.

A new visitor centre is set to open in July, which will tell the story of the king’s life, his brutal death in Battle in 1485 and rediscovery of his remains.

Magna Carta

Allan Massie says there was “nothing revolutionary” about the signing of the Magna Carta on June 15, 1215:

The document was presented to the king and his signature, by seal, extracted. He had violated so many customs of the realm and infringed long-established liberties, which we might rather call privileges, that his rule in its present form had become intolerable to the barons and landholders, to the Church, and to the merchants of boroughs protected by their own charters.

The Magna Carta rehearsed these customs and liberties. It was a reproof to the king, to compel him to mend his ways. Far from being an abstract statement of rights, it was a practical document: calling the king to order, reminding him of the limits on his power, and insisting that he was not above the law, but subject to it.

This was not unusual. Kings had been brought to a similar point before. Medieval monarchy was limited monarchy, in theory and of necessity. Kings had to govern in collaboration with “the Community of the Realm” (essentially the propertied classes) and with their consent. Ultimately, having neither a standing army nor a police force, they had little choice. Moreover, the society of the Middle Ages was intensely legalistic – and the purpose of Magna Carta was to remind the king of what the laws were and of his duty to observe them if he himself was to receive loyalty and obedience.

If Shakespeare makes no mention of the document it is because in the years of the Tudor despotism the balance between government and governed shifted in favour of the former. The Tudors made use of what were called the Prerogative Courts to bypass the common law of England. Torture, practised on “subversive” Roman Catholics by the Elizabethan government, was illegal under the common law (and indeed under Magna Carta), but inflicted by the judgment of the Prerogative Courts (the Star Chamber and High Commission).

It was the parliamentary and judicial opposition to the less effective (and less oppressive) despotism of the early Stuarts which revived interest in Magna Carta, now presented as the safeguard or guarantee of English liberty. Though it had been drawn up by Anglo-Norman bishops and presented to the king by Anglo-Norman barons, the theory was developed that it represented a statement of the rights and liberties enjoyed in Anglo-Saxon England by the “free-born” Englishmen before they were subjugated to the “Norman Yoke”.

This, doubtless, offered an unhistorical and rather-too-rosy view of Anglo-Saxon England before the Norman Conquest, but it had this to be said for it: that the Norman and Plantagenet kings had regularly promised to abide by the “laws of King Edward” – the saintly “Confessor” and second-last Saxon king.

June 10, 2014

England’s World Cup team – where’s the hype?

BBC News Magazine has expatriot Scot Jon Kelly wondering where all the traditional pro-England hype has gone, compared to previous World Cup campaigns:

The flags are missing from the cars. British newspapers aren’t heralding imminent victory. In pubs from Penrith to Plymouth there’s a distinct lack of gaiety, optimism and hope.

I for one couldn’t be happier.

As a Scotsman resident in London, I’ve come to dread the wildly delusional over-confidence that grips my adopted homeland every time an international football tournament is staged.

The certainty of victory. The talk of a “golden generation”. The interminable references to 1966. And the inevitable splutterings of anguish when it’s eventually confirmed on the pitch that, actually, Germany or Argentina or Portugal are superior teams after all.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I like all things Anglo very much. While Scotland will always be the national side I support, in spite of our dependable rubbishness, I’ve always felt the Anyone-But-England tendency among some of my fellow Scots diminishes our status as a self-confident, modern nation.

1966 – it seems like only yesterday to many England fans

But the bellicose hysteria that envelops many in England — not to mention the irritating assumption by certain broadcasters, newspapers and advertisers that their audiences are comprised entirely of England fans — makes the team in white a difficult one for non-English folk to like, never mind cheer on.

And I say all this as someone who takes an interest in football. For those who dislike the game, it must be excruciating.

This year it’s different, however. No-one with more than a cursory knowledge of the international game seriously believes England will win.

That much is true: if they stick to the traditional formula, they’ll go out on penalties in the quarter-finals.

Invariably, a motley crew of psychologists, positive-thinking gurus and snake-oil sellers will be forming a queue outside FA headquarters, offering cures for the English penalty curse. I think there’s a simpler solution. Let’s campaign for spot kicks to be scrapped. We should use whatever arguments we think might work. I’d play the inclusion card. Penalty kicks clearly discriminate against the mentally frail. The English, who suffer from a collective, penalty-induced trauma, will always get a raw deal. How can that be fair? If FIFA wants a truly level playing field, the answer is to get rid of the pseudo-lottery of spot kicks. What we need is a proper lottery. We don’t want skill or nerve to play any part. Tossing a coin, rolling dice, drawing straws, a game of scissor-paper-stone — anything is better than a shootout. Come on Mr Blatter, give us chokers a chance.

Still one of my favourite World Cup comments (and I’m flying the English flag for the tournament):

Erectile dysfunction is on the increase. If you suffer please put a whiteflag with a redcross on your car to show your support #england #lfc

— pheadtony (@pheadtony) June 1, 2010

May 30, 2014

“Historical” High Court judgment that ignores history

Last week, the High Court decided that the remains of King Richard III will be re-buried in Leicester, not in York. As you might expect, that leaves a lot of people unhappy.

When Richard III was hacked to death in rural Leicestershire in 1485, the royal House of York fell, bringing an end to the Plantagenet line that had lasted for 16 kings and 331 years. Many people see his death as the end of the English middle ages.

Despite this country’s ancient legal system, the courts do not often get to deal with real history, although they make many historic decisions. Yet the ruling of the High Court last Friday truly made history, as three judges decided that Richard III should be buried at the scene of his violent defeat, and not in York.

One side is always unhappy after a court hearing. And in this case those who sponsored York Minster may have more to be sore about than most.

The High Court acknowledged the case has “unprecedented” and “unique and exceptional features,” but nevertheless went on to give a rather bland ruling supporting Chris Grayling’s decision to leave the matter of reburial in the hands of the University of Leicester team running the excavation. In doing so, the court treated the hearing as a straightforward matter of public law, and affirmed that the government had been under no duty to consult widely before handing the responsibility over to the University of Leicester.

[…]

History and legacy mattered to medieval monarchs. Their actions, even the less obvious ones, were intended to make statements to reinforce their dynastic power. York Minster is an ancient foundation, home to the throne of the second most senior churchman in England. There has been an Archbishop of York since at least the seventh century. For Richard, a scion of the house of York, the Minster was an obvious place to fuse the sacred and secular, binding royal and church power together in one of England’s most venerable religious buildings. By contrast, Leicester Cathedral, although a lovely building with a long tradition of worship on the site, was a parish church until 1927 when it became the city’s cathedral. Although there was a church there in Richard’s day, it does not have the dynastic associations that Richard was clearly building with York.

And there’s always the religious aspect to consider (which would have been true regardless of the High Court’s decision):

And finally, the question of the liturgy is also set to run. As the old joke goes: Q. What is the difference between a terrorist and a liturgist? A. You can reason with a terrorist. Leicester cathedral has diligently teamed up with an expert medieval musicologist, who has painstakingly uncovered and proposed the finer details of prayers and music appropriate to a 15th-century reburial. However, strong feelings which go beyond the musical arrangements have been expressed in many quarters, including in an online petition, and by Dr John Ashdown-Hill, the historian who led the excavations. These views reflect a conviction that Richard should have a Roman Catholic ceremony that respects the faith in which he grew up and died, and which is honest to what his wishes would have been. Leicester Cathedral will certainly have their hands full trying to reconcile Richard’s pre-Reformation religious beliefs with the Church of England ceremonies they are permitted to conduct.

May 28, 2014

The “servant problem” of post-Victorian England

Before the widespread availability of electricity, no middle class household in England could get by without at least one servant. Even as modern labour-saving appliances (along with proper plumbing) started to take their place in the home, servants were still deemed an essential part of being middle- or upper-class. It may account for some of the fascination with TV shows like Downton Abbey or the earlier Upstairs, Downstairs to modern audiences — they give at least a bit of a glimpse into a very different domestic world. At Bookforum, Daphne Merkin reviews a books that look at the “servant problem”:

Servants is chockablock with incredulous-making details about the exploitative conditions in which household help lived and worked (these included cramped, chilly, and spartan sleeping quarters, endless hours, and the overriding assumption of inferiority), as well as anecdotes of supreme helplessness on the part of the coddled rich, such as the following: “Lord Curzon, whose intellect was regarded as one of the glories of the Empire, was so baffled by the challenge of opening a window in the bedroom of the country house in which he was staying (no servants being available so late at night), that he simply picked up a log from the grate and smashed the glass.” Even after World War II, when homes had begun to be wired for electricity despite the gentry’s insistence on the vulgarity of such improvements and the ideal of the 1950s self-contained (and servantless) housewife was hoving into view, so otherwise gifted a chap as Winston Churchill was unable, according to his valet John Gibson, to dress himself without assistance: “He was social gentry … He sat there like a dummy and you dressed him.” As easy as it is to snicker at such colossal ineptitude on the part of the cultural elite, it is also intriguing to consider how this kind of infantilizing treatment might have facilitated their performance in demanding grown-up roles — like someone playing with rubber ducks in the bath before going out to lead men in a military campaign.

Servants takes the reader from the days of Welbeck Abbey, the home of the eccentric and reclusive Duke of Portland, where upper servants had their own underservants to wait on them, to the gradual erosion of the older forms of domestic service and on up through the new world of do-it-yourself home comforts as devised by technology and a greater show of equality between employer and servant. This world, ushered in with the 1950s, shunned the “badge of servitude” that was conveyed by uniforms, surreal daily routines (whether it meant Ladyships who couldn’t sleep with creases on a pillowcase or Ladyships who insisted on cutting their boiled eggs with a letter opener), and a feudal attitude that took no more cognizance of domestics than it did of the furniture. “It was in the best houses considered quite unnecessary (in fact poor form),” Lethbridge notes, “for servants to knock before entering a room. This was partly because they lived in such everyday familiarity with the family that there was nothing to hide from them and partly because … their presence made no difference whatsoever to whatever was being said or going on.”

[…]

There’s much to think about in both these books — not least the particularly British style of treating domestics, both less casually sadistic and less casually amorous than, say, white Americans’ attitude toward black slaves. Indeed, I suspect that one of the reasons American audiences delight in the travails and triumphs of the gaggle of domestics on Downton Abbey is out of a sense of superiority that the “servant problem” in such acute, institutionalized form isn’t ours. Much as we may envy them all that pampering, we also like to look down our noses at it as going against the democratic and independent Yankee ethos. To this point it’s worth noting that Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique referred precisely to “the servant problem” as one of the besetting woes of the upper-middle-class housewives she was looking to liberate, and that our habit of befriending those who clean our kitchens and bathrooms and look after our children can’t disguise the fact that we value their hourly labor less than we value a twenty-minute haircut and that we live largely in ignorance of their thoughts and feelings.

England’s sorry World Cup history

Published on 27 May 2014

James Richardson updates the story of England, through the occasional ups and regular downs of the English national side, from the first international ever played in 1872 (a 0-0 thriller with Scotland) to the present day, via glory in 1966 and failure, well, pretty much all the rest of the time

Yep, the World Cup is coming up soon. Here are the opening fixtures for each of the groups:

Note the joyful placement of England (#11 in the world rankings) with Uruguay (#6) and Italy (#9). Much angst to be enjoyed as the round-robin plays out… Of course, if England is looking to an uphill struggle to get out of the group stage, imagine how Costa Rica is feeling (currently #34 in the world rankings). And Canadians can’t poke too much fun … we rank #110 at the moment.