Lester Haines reports on a recent record auction price for an Enigma machine:

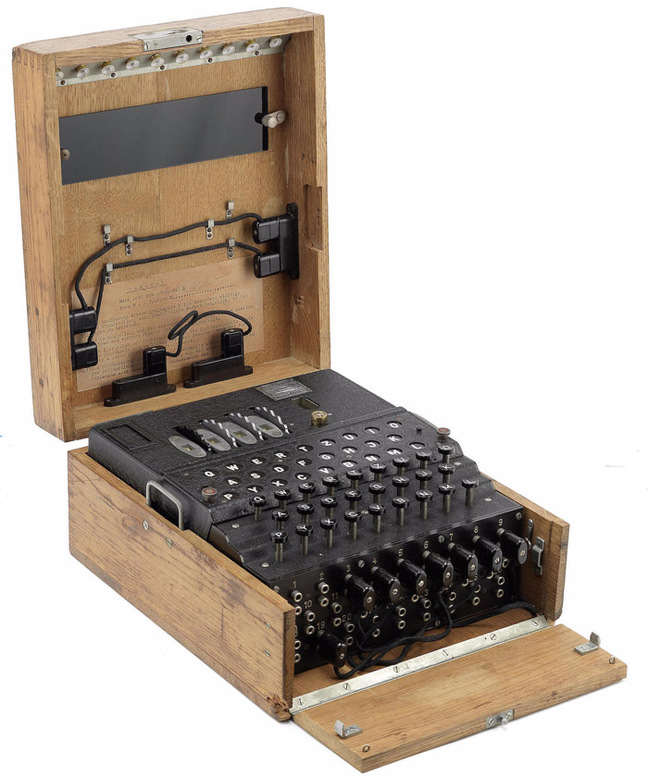

A fully-functioning four-rotor M4 Enigma WW2 cipher machine has sold at auction for $365,000.

The German encryption device, as used by the U-Boat fleet and described as “one of the rarest of all the Enigma machines”, went under the hammer at Bonham’s in New York last night as part of the “Conflicts of the 20th Century” sale.

The M4 was adopted by the German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, in early 1942 following the capture of U-570 in August 1941*. Although the crew of U-570 had destroyed their three-rotor Enigma, the British found aboard written material which compromised the security of the machine.

The traffic to and from the replacement machines was dubbed “Shark” by codebreakers at Bletchley Park. Decryption proved troublesome, due in part to an initial lack of “cribs” (identified or suspected plaintext in an encrypted message) for the new device, but by December 1942, the British were regularly cracking M4 messages.

I recently read David O’Keefe’s One Day in August, which seems to explain the otherwise inexplicable launch of “Operation Jubilee”, the Dieppe raid … in his reading, the raid was actually a cover-up operation while British intelligence operatives tried to snatch one or more of the new Enigma machines (like the one shown above) without tipping off the Germans that that was the actual goal. Joel Ralph reviewed the book when it was released:

One Day in August, by David O’Keefe, takes a completely different approach to the Dieppe landing. With significant new evidence in hand, O’Keefe seeks to reframe the entire raid within the context of the secret naval intelligence war being fought against Nazi Germany.

On February 1, 1942, German U-boats operating in the Atlantic Ocean switched from using a three-rotor Enigma code machine to a new four-rotor machine. Britain’s Naval Intelligence Division, which had broken the three-rotor code and was regularly reading German coded messages, was suddenly left entirely in the dark as to the positions and intentions of enemy submarines. By the summer of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic had reached a state of crisis and was threatening to cut off Britain from the resources needed to carry on with the war.

O’Keefe spends nearly two hundred pages documenting the secret war against Germany and the growth of the Naval Intelligence Division. What ties this to Dieppe and sparked O’Keefe’s research was the development of a unique naval intelligence commando unit tasked with retrieving vital code-breaking material. As O’Keefe’s research reveals, the origins of this unit were at Dieppe, on an almost suicidal mission to gather intelligence they hoped would crack the four-rotor Enigma machine.

O’Keefe has uncovered new documents and first-hand accounts that provide evidence for the existence of such a mission. But he takes it one step further and argues that these secret commandos were not simply along for the ride at Dieppe. Instead, he claims, the entire Dieppe raid was cover for their important task.

It’s easy to dismiss O’Keefe’s argument as too incredible (Zuehlke does so quickly in his brief conclusion [in his book Operation Jubilee, August 19, 1942]). But O’Keefe would argue that just about everything associated with combined operations defied conventional military logic, from Operation Ruthless, a planned but never executed James Bond-style mission, to the successful raid on the French port of St. Nazaire only months before Dieppe.

Clearly this commando operation was an important part of the Dieppe raid. But, while the circumstantial evidence is robust, there is no single clear document that directly lays out the Dieppe raid as cover for a secret “pinch by design” operation to steal German code books and Enigma material.