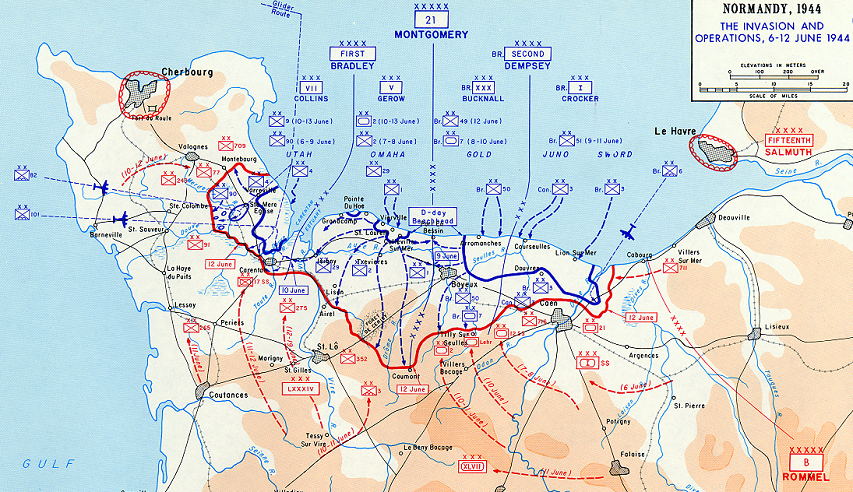

Seventy years ago today, the Allies launched Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy by the combined British, American, and Canadian armies. A huge fleet of combat and transport vessels, supported by a large proportion of the United States Army Air Force and the Royal Air Force bomber and fighter aircraft were all deeply involved in making the invasion a success. In addition, perhaps the world’s largest disinformation campaign was being run to keep the German high command unsure of the real time and location of the invasion: the Pas de Calais and the Norwegian coast were also potential invasion targets, forcing the defenders to spread their forces thinner and to keep as many as possible out of reach of the real beaches.

In addition to the operational uncertainty of where to expect the blow, the Germans were also split about how best to conduct the defence: Field Marshal Rommel wanted to rush units to the beach as soon as possible, to defeat the Allies before they got inland. General Geyr von Schweppenburg, commander of Panzer Group West (and Field Marshal von Rundstedt, overall commander in the West), on the other hand, preferred to meet the Allies further inland (not taking the full impact of Allied air superiority into account). On 6 June, the defenders fell between the two philosophies, not being able to mass enough force to stop the invaders in their tracks, but suffering higher casualties in the attempt to move units toward the coast in the teeth of RAF/USAAF attacks.

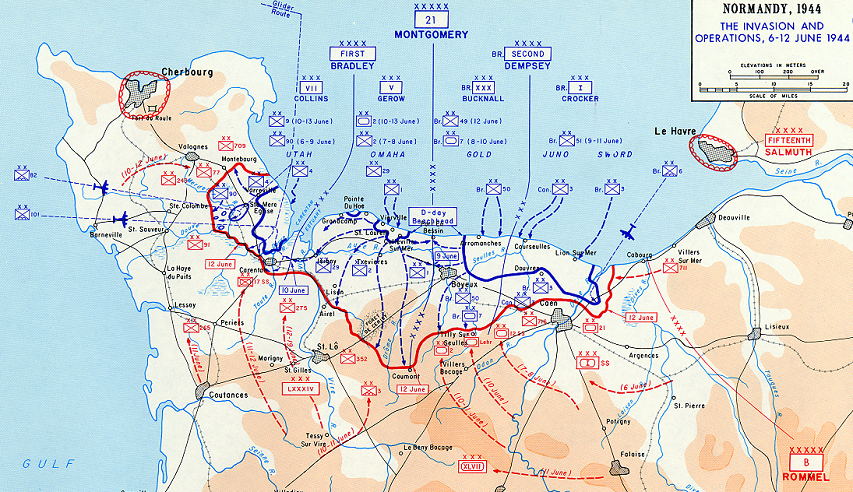

Operation Overlord (detail) Click to see full-sized image at wwii-info.net

The invasion beaches were code-named Utah (4th US Division), Omaha (1st and 29th US divisions), Gold (50th British Division), Juno (3rd Canadian Division), and Sword (3rd British Division). Before the amphibious forces landed, three paratroop divisions were dropped behind the beaches to slow down German response (US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to the West and Southwest of Utah beach, and the 6th British Airborne to the East of Sword beach).

One thing to note from the map is that there wasn’t a significant port within the invasion zone: the Allies had learned the bitter lessons of attacking a port in August of 1942 and the 2nd Canadian Division had paid in blood for the tuition. This meant a way had to be found to keep getting supplies to the troops after they moved off the beaches, until a functioning port could be secured. The Allied answer was to bring a port with them from England — two of them, actually — one to support the US forces in the West and one to support the British and Canadian forces in the East. These were the Mulberry harbours:

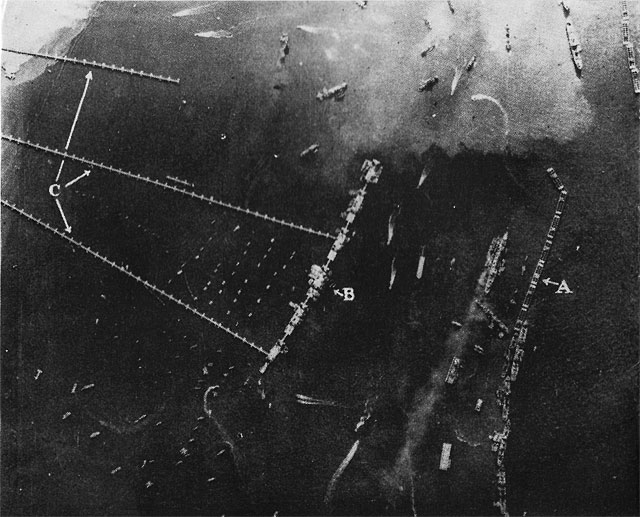

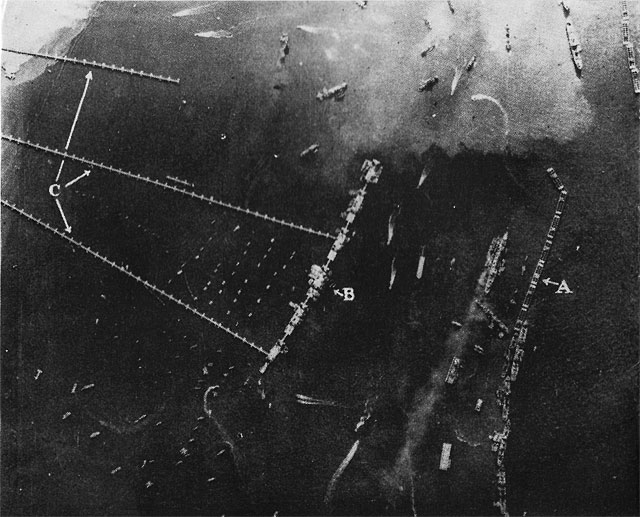

Think Defence explains how the Mulberry harbour worked:

In the image above these three components are shown.

A; Breakwater to attenuate waves

B; Pier heads at which to load and unload

C; Causeways that connected the pier heads to the beach

Each of the components was given a code word but fundamentally, they were concerned with either providing sheltered water or connecting ships and the beach.

There have been a number of different theories about how the Mulberry name was chosen, the more fanciful ones being completely incorrect.

Brigadier White recalls the moment he received a memo, unclassified, with the heading ‘Artificial Harbours’ and after recovering from the shock of such poor security immediately consulted with the Head of Security at the War Office. The next code, from the big book of code words, was Mulberry, it was that simple.

[…]

There were two complete Mulberry harbours, A for American and B for British, each the size of Dover harbour. Once the task of constructed and assembling the components on the South coast of England was complete they were ordered to Normandy on the 6th of June 1944, D-Day, departing on the 7th

Assembling the components was an effort in itself, requiring 600 tugs drawn from all parts of the UK and USA, all under the supervision of the Admiralty Towing Section commanded by Rear Admiral Brind.

Operational security was paramount, the captains of the block ships were told they were going to the Bay of Biscay and a model of the Mulberry harbour and invasion beaches in the headquarters of the Automobile Association at Fanum House was made by toymakers who were confined to the building until well after the invasion.

Unfortunately, the Western harbour was severely damaged in a storm a few weeks after coming into service, so the Eastern Mulberry had to do double duty after that.

Aside from the need to get reinforcements, rations, ammunition and other supplies forward, the Allied armies were highly motorized, and required vast amounts of fuel. Without a port’s specialized unloading facilities, it was assumed that it would be somewhere between difficult and impossible to keep the armies mobile. To address this, PLUTO was developed: Pipe Line Under The Ocean.

A great solution, although as Think Defence points out, it didn’t actually go into service until a few months after D-Day, and was not quite the war-winner the newsreel portrayed:

Second in daring only to the artificial harbors project and provided our main supplies of fuel during the Winter and Spring campaigns.

What also PLUTO did was allow vital tanker tonnage to be deployed to the Far East theatre.

Despite the understandable over exaggeration of the success of PLUTO it should be noted that fuel did not start flowing until September 1944, well after the invasion and on the 4th of October, BAMBI was closed down and operations concentrated on DUMBO after it had delivered a measly 3,300 tonnes, hardly war winning.

Cherbourg was by then receiving tanker supplies direct from the USA.

Getting across the channel was a major undertaking, but getting the troops ashore with enough firepower to break out of the beach defences required more innovation. The British army established a specialized unit to develop and operate vehicles and weapon systems specifically designed for that purpose. Major General Sir Percy Hobart was the commander of the 79th Armoured Division, and he was exactly the right man for the job (being related by marriage to Montgomery may have helped, too, but before taking command he was acting as a corporal in the Home Guard).

Getting across the channel was a major undertaking, but getting the troops ashore with enough firepower to break out of the beach defences required more innovation. The British army established a specialized unit to develop and operate vehicles and weapon systems specifically designed for that purpose. Major General Sir Percy Hobart was the commander of the 79th Armoured Division, and he was exactly the right man for the job (being related by marriage to Montgomery may have helped, too, but before taking command he was acting as a corporal in the Home Guard).

Hobart’s unit developed some of the most interesting armoured vehicles (not all of which were brilliant successes) and it’s safe to say that the Allies would have suffered much higher casualties without Hobart’s “Funnies”. In fact, General Eisenhower said as much himself: “Apart from the factor of tactical surprise, the comparatively light casualties which we sustained on all beaches, except OMAHA, were in large measure due to the success of the novel mechanical contrivances which we employed, and to the staggering moral and material effect of the mass of armor landed in the leading waves of the assault. It is doubtful if the assault forces could have firmly established themselves without the assistance of these weapons.” Think Defence has a good summary of many of these odd and interesting vehicles:

Sherman tanks were also converted into amphibious vehicles by the addition of a canvas skirt, propellers and other modifications. These provided vital armoured fire support in the opening phase of the beach assault although a number were lost to the heavy seas when they were launched too far from the beach. It is widely thought that as these losses were particularly heavy on Omaha beach it was this that contributed to the very high losses in that area.

Mine clearance was carried out by a number of means but the preferred method was to use rotating chain flails to detonate the mines thus clearing a path the width of the tank. The flails were mounted on the front of the tank and were called Sherman Crabs. A number of Churchill based designs using rollers and ploughs were also employed, although this image shows one mounted on a Sherman.

The beach surveys had revealed the existence of large patches of clay that would not bear the weight of heavy vehicles and artillery. To overcome this the ‘bobbin’ tanks were used that laid a continuous reinforced canvas mat over the soft ground, thus spreading the load over a wider area.

Getting across the channel was a major undertaking, but getting the troops ashore with enough firepower to break out of the beach defences required more innovation. The British army established a specialized unit to develop and operate vehicles and weapon systems specifically designed for that purpose. Major General Sir Percy Hobart was the commander of the

Getting across the channel was a major undertaking, but getting the troops ashore with enough firepower to break out of the beach defences required more innovation. The British army established a specialized unit to develop and operate vehicles and weapon systems specifically designed for that purpose. Major General Sir Percy Hobart was the commander of the