Dan Mitchell clearly understands what modern western government is really all about:

May 24, 2015

May 23, 2015

Debunking the “GM killed the streetcars” conspiracy theory

There are many railfans who still believe, strongly and passionately, that General Motors was involved in a devious plot to kill off the streetcars across North America in order to sell more buses. At Vox.com, Joseph Stromberg explains that this wasn’t the case — in fact, the killer of the streetcar/interurban/radial railway systems was their willingness to lock in to long-term uneconomic agreements with local governments in exchange for monopoly privileges:

Back in the 1920s, most American city-dwellers took public transportation to work every day.

There were 17,000 miles of streetcar lines across the country, running through virtually every major American city. That included cities we don’t think of as hubs for mass transit today: Atlanta, Raleigh, and Los Angeles.

Nowadays, by contrast, just 5 percent or so of workers commute via public transit, and they’re disproportionately clustered in a handful of dense cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago. Just a handful of cities still have extensive streetcar systems — and several others are now spending millions trying to build new, smaller ones.

So whatever happened to all those streetcars?

“There’s this widespread conspiracy theory that the streetcars were bought up by a company National City Lines, which was effectively controlled by GM, so that they could be torn up and converted into bus lines,” says Peter Norton, a historian at the University of Virginia and author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.

But that’s not actually the full story, he says. “By the time National City Lines was buying up these streetcar companies, they were already in bankruptcy.”

Surprisingly, though, streetcars didn’t solely go bankrupt because people chose cars over rail. The real reasons for the streetcar’s demise are much less nefarious than a GM-driven conspiracy — they include gridlock and city rules that kept fares artificially low — but they’re fascinating in their own right, and if you’re a transit fan, they’re even more frustrating.

This is one of the reasons I’m generally against new plans to re-introduce streetcars (or their modern incarnations generally grouped under the term “light rail”), because they fail to address one of the key reasons that the old street railway/interurban/radial systems died: they were sharing road space with private vehicles. Light rail can provide a useful urban transportation option if they have their own right-of-way, but not if they are merely adding to the gridlock of already overcrowded city streets.

And once again, I’m not anti-rail … I founded a railway historical society and I commute most work days on a heavy rail commuter network. I don’t hold this position due to some anti-rail animus. If anything, I regret the passing of railway systems more than most people do, but I recognize that they have to be self-supporting (or close to self-supporting) to have a chance to survive. Being both more expensive and less convenient than alternative transportation options is a sure-fire path to extinction.

May 15, 2015

This is why California’s water shortage is really a lack of accurate pricing

David Henderson explains:

Of the 80 million acre feet a year of water use in California, only 2.8 million acre feet are used for toilets, showers, faucets, etc. That’s only 3.5 percent of all water used.

One crop, alfalfa, by contrast, uses 5.3 million acre feet. Assuming a linear relationship between the amount of water used to grow alfalfa and the amount of alfalfa grown, if we cut the amount of alfalfa by only 10 percent, that would free up 0.53 million acre feet of water, which means we wouldn’t need to cut our use by the approximately 20 percent that Jerry Brown wants us to.

What is the market value of the alfalfa crop? Alexander quotes a study putting it at $860 million per year. So, assuming, for simplicity, a horizontal demand curve for alfalfa, a cut of 10% would reduce alfalfa revenue by $86 million. (With a more-realistic downward-sloping demand for alfalfa, alfalfa farmers would lose less revenue but consumers would pay more.) With a California population of about 38 million, each person could pay $2.26 to alfalfa growers not to grow that 10%. Given that the alfalfa growers use other resources besides water, they would be much better off taking the payment.

April 11, 2015

America’s biggest welfare queen

It’s not nice to call someone a welfare queen, but this is a case where it’s hard to find a more accurate way of putting it:

America’s biggest welfare queen is someone you’ve probably never heard of. She’s Hispanic. She’s been living off other people’s hard-earned tax money for years. And she’s gotten rich doing it.

Her name is Iberdrola. She’s a Spanish energy company that has invested in U.S. power facilities. And according to the advocacy group Good Jobs First, she’s raked in more than $2 billion from Uncle Sam in just the past few years.

Good Jobs First maintains a subsidy tracker where you can look up which companies are getting rich from public funds. It recently issued a report on “Uncle Sam’s Favorite Corporations — the companies that have gained the most from federal grants, special tax preferences, loans, and loan guarantees.

The biggest beneficiaries (“by an order of magnitude”) are Bank of America, Citigroup, and other major financial institutions that were bailed out during the 2008 financial crisis. The Federal Reserve, the Troubled Asset Relief Program, and so on threw trillions of dollars at U.S. and foreign banks in a desperate effort to stabilize the financial system. It worked. In many cases (though not all), the institutions repaid the money. In some cases the federal government actually earned a profit.

But hundreds of other companies have raked in billions of dollars in direct grants. Along with Iberdrola, NextEra Energy, NRG Energy, Southern Company, Summit Power, and SCS Energy all have reaped more than $1 billion in federal largess, often receiving payments through programs meant to boost renewable energy. At the same time, many coal companies have taken huge sums from Washington through grants and coal production tax credits. So, as with farm programs—some of which subsidize farmers to farm more and some of which pay farmers to not farm at all—Washington thwarts its own objectives by subsidizing both renewable fuel sources and the fossil fuels they’re supposed to replace.

April 7, 2015

Regulating the US railroads

At Slate Star Codex, Scott Alexander recently reviewed David Friedman’s latest revision to his 1973 book, The Machinery of Freedom (sometimes called The Machinery of Friedman by libertarian wags). Scott wasn’t totally sold on Friedman’s proposals, but he posted several highlights from the book, including this discussion of how the US government was persuaded to regulate the railroad industry and then the airlines:

One of the most effective arguments against unregulated laissez faire has been that it invariably leads to monopoly. As George Orwell put it, “The trouble with competitions is that somebody wins them.” It is thus argued that government must intervene to prevent the formation of monopolies or, once formed, to control them. This is the usual justification for antitrust laws and such regulatory agencies as the Interstate Commerce Commission and the Civil Aeronautics Board.

The best historical refutation of this thesis is in two books by socialist historian Gabriel Kolko: The Triumph of Conservatism and Railroads and Regulation. He argues that at the end of the last century businessmen believed the future was with bigness, with conglomerates and cartels, but were wrong. The organizations they formed to control markets and reduce costs were almost invariably failures, returning lower profits than their smaller competitors, unable to fix prices, and controlling a steadily shrinking share of the market.

The regulatory commissions supposedly were formed to restrain monopolistic businessmen. Actually, Kolko argues, they were formed at the request of unsuccessful monopolists to prevent the competition which had frustrated their efforts.

[…]

It was in 1884 that railroad men in large numbers realized the advantages to them of federal control; it took 34 years to get the government to set their rates for them. The airline industry was born in a period more friendly to regulation. In 1938 the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), initially called the Civil Aeronautics Administration, was formed. It was given the power to regulate airline fares, to allocate routes among airlines, and to control the entry of new firms into the airline business. From that day until the deregulation of the industry in the late 1970s, no new trunk line — no major, scheduled, interstate passenger carrier — was started.

The CAB had one limitation: it could only regulate interstate airlines. There was one major intrastate route in the country — between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Pacific Southwest Airlines, which operated on that route, had no interstate operations and was therefore not subject to CAB rate fixing. Prior to deregulation, the fare between San Francisco and Los Angeles on PSA was about half that of any comparable interstate trip anywhere in the country. That gives us a good measure of the effect of the CAB on prices; it maintained them at about twice their competitive level.

In this complicated world it is rare that a political argument can be proved with evidence readily accessible to everyone, but until deregulation the airline industry provided one such case. If you did not believe that the effect of government regulation of transportation was to drive prices up, you could call any reliable travel agent and ask whether all interstate airline fares were the same, how PSA’s fare between San Francisco and Los Angeles compared with the fare charged by the major airlines, and how that fare compared with the fare on other major intercity routes of comparable length. If you do not believe that the ICC and the CAB are on the side of the industries they regulate, figure out why they set minimum as well as maximum fares.

March 25, 2015

Reason.tv – Sports Stadiums Are Bad Public Investments. So Why Are Cities Still Paying for Them?

Published on 17 Mar 2015

“Anybody that drives around Southern California can tell you the infrastructure is falling apart,” says Joel Kotkin, a fellow of urban studies at Chapman University and author of the book The New Class Conflict. “And then we’re going to give money so a bunch of corporate executives can watch a football game eight times a year? It’s absurd.”

When the Inglewood City Council voted unanimously to approve a $1.8 billion stadium plan on February 24th, hundreds of football fans in attendance cheered for the prospect of a team finally returning to the Los Angeles area.

On it’s face, the deal for the city of Inglewood is unprecedented — Rams owner Stan Kroenke has agreed to finance construction of the stadium entirely with private funds. The deal makes the stadium one of the most expensive facilities ever built and is an oddity in the sports world, where most stadiums require millions in public dollars to be constructed.

And while the city still waits to hear if it will indeed inherit an NFL team, the progress on the new privately-funded Inglewood stadium has set off a bidding war between other cities that are offering up millions in public subsidies to keep (or attract) pro-sports franchises to their area.

St. Louis has proposed a billion dollar waterfront stadium financed with $400 million in tax money to keep the Rams in Missouri. And the San Diego Chargers and Oakland Raiders have unveiled a plan to turn a former landfill in Carson, California, into a $1.7 billion stadium to keep the Rams from encroaching on their turf. While full details of the plan have yet to be released, it’s been reported that the financing would be similar to the San Francisco 49er’s deal in Santa Clara, which saw the team receive $621 million in construction loans paid for with public money.

Even the fiscally conservative Scott Walker is not immune to the stadium spending craze. The Wisconsin governor wants to allocate $220 million in public bonds to keep the Milwaukee Bucks basketball franchise in the area. Walker has dubbed the financing scheme as the “Pay Their Way” plan, but professional sports teams rarely pay their fair share when it comes to stadiums and instead use public money to generate private revenue.

Pacific Standard magazine has reported that in the last 20 years, the U.S. has opened 101 new sports facilities and stadium finance experts say that almost all of them have received public funding totaling billions of dollars. Politicians generally rationalize this expense by stating that stadiums will generate economic revenue and job opportunities for the city, but Kotkin says those promises are rarely realized.

“I think this is sort of a fanciful approach towards economic development instead of building really good jobs. And except for the construction, the jobs created by stadia are generally low wage occasional work.”

“The important thing that we’ve forgotten is ‘What is the purpose of a government?'” asks Kotkin. “Cities instead of fixing their schools, fixing their roads or fixing their sewers or fixing their water are putting money into ephemera like stadia. And in the end, what’s more important?”

March 22, 2015

March 13, 2015

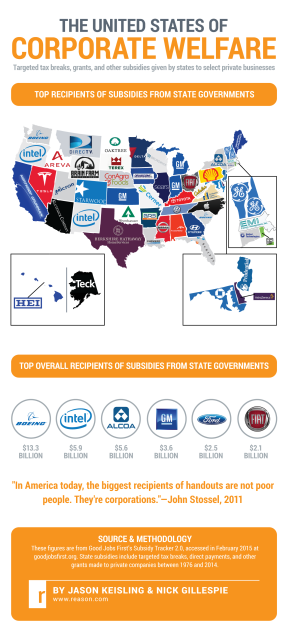

US corporate welfare by state

Reason posted an infographic showing which corporation gets the most state support for every state in the union:

March 2, 2015

QotD: The environmental sins of ethanol

Ethanol, produced by corn, “biomass,” cane sugar or other plant matter, is considered by many to be a great alternative to fossil fuels. They consider the origin to be more renewable (plants grow rapidly), the fuel to produce less pollution, the production to release fear “carbon emissions,” and as a bonus, it costs more so people might drive less.

Ethanol is so beloved by some that legislation to subsidize farmers who grew crops for biofuels was pushed through in many countries including Germany and the United States. It would save us from dependence on foreign oil, it would reduce pollution, and cars can run on plants, won’t that be wonderful? Some even argue that it would reduce gas prices because we could shake that oil addiction from the middle east and produce it here cheaply and efficiently!

The truth is, ethanol has its advantages. When burned, it pollutes less than straight gasoline, and it actually has a higher octane rating, making it produce more horsepower per weight than gasoline. It also burns somewhat cooler than straight gasoline.

These days ethanol is less popular, and you don’t hear so much about how great it is. BP isn’t running bright green ads with happy cars driving around on corn any more. But the legislation is still in place, the farmers are still growing corn to turn into fuel, and any attempt to stop this or repeal the legislation is met with exactly the same environmental claims and protests.

So what about these fuels, are they really that great? Are people who oppose ethanol just oil company stooges?Greg Giraldo is dead now, but he was a very brilliant, very funny comedian. He was one of those comedians that all other comedians loved and thought was so hilarious but for some reason never really caught on or broke big.

He had a bit on biofuels in which he pointed out that for every gallon of corn ethanol, it requires two gallons of gasoline to produce. He noted the only reason corn ethanol is even pushed is because corn farmers want that sweet subsidy money. Al Gore not long ago admitted it wasn’t about the environment, but about kickbacks to farmers for political gain:

First generation ethanol I think was a mistake. The energy conversion ratios are at best very small. […] One of the reasons I made that mistake is that I paid particular attention to the farmers in my home state of Tennessee, and I had a certain fondness for the farmers in the state of Iowa because I was about to run for president.

Every so often a politician will be honest.

The truth is, ethanol is not just a failure in every single category it was supposed to succeed, but a disaster. From food shortages to riots, to slavery and beyond, ethanol in all its forms is a horrific failure. Let us count the ways.

Christopher Taylor, “COMMON KNOWLEDGE: Ethanol and Biofuels “, Word Around the Net, 2014-04-25.

March 1, 2015

“The F-35 will cost more than the Manhattan Project every year for the next fifty years”

Scott Lincicome would like to point out to the contending Republicans hoping to become the GOP’s presidential candidate that defence spending is not immune to the massive overspending problem common to big government:

Over the next 20 months, a clown-car-full of Republican politicians will vie for their party’s presidential nomination. As the candidates crisscross the nation, each will undoubtedly call for smarter, leaner, and (hopefully) smaller government. However, there is one government program that, despite being a paragon of government incompetence and mind-bending fiscal incontinence, will most likely be ignored by these champions of budgetary temperance: the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. In so doing, these Republicans will abandon their principles and continue a long, bipartisan tradition of perpetuating the broader problems with U.S. defense spending that the troubled jet symbolizes.

During the Obama years, the Republican Party magically rediscovered its commitment — at least rhetorically — to limited government and fiscal sanity. Criticizing the graft, incompetence, and cost of boondoggles like the 2009 stimulus bill, green-energy subsidies, or Obamacare, GOP politicians not only highlighted these programs’ specific failings, but also often explained how such problems were the inevitable result of an unwieldy federal government that lacked discipline and accountability and was inherently susceptible to capture by well-funded interest groups like unions or insurance companies.

They railed against massive bureaucracies, like the Department of Energy, that paid off cronies with scant congressional oversight. And, in the case of well-publicized debacles like the botched, billion-dollar Healthcare.gov roll-out, many Republicans were quick to note that the root of the problem lay not in one glitchy website, but the entire federal procurement process, and even Big Government itself

[…]

One wonders, however, if these Republicans’ philosophical understanding of Big Government’s inherent weaknesses extends to national defense and, in particular, the F-35. According to the latest (2012) estimate from the Pentagon, the total cost to develop, buy and operate the F-35 will be $1.45 trillion — yes, trillion, with a “t” — over the next 50 years, up from a measly $1 trillion estimated in 2011. For those of you keeping score at home, this means that the F-35’s lifetime cost grew about $450 billion in one year. (Who says inflation is dead?)

That number — $1.45 trillion — might be difficult to grasp, especially in the context of U.S. defense spending, so let me try to put it in perspective: the entire Manhattan Project, which took around three years and led to the development of the atom bomb, cost a total of $26 billion (2015), most of which went to “building factories and producing the fissile materials, with less than 10% for development and production of the weapons.” By contrast, the F-35 will cost $29 billion. Per year.

For the next 50 years.

January 10, 2015

The four kinds of healthcare spending

Megan McArdle explains why healthcare costs more than you think it should:

Milton Friedman famously divided spending into four kinds, which P.J. O’Rourke once summarized as follows:

- You spend your money on yourself. You’re motivated to get the thing you want most at the best price. This is the way middle-aged men haggle with Porsche dealers.

- You spend your money on other people. You still want a bargain, but you’re less interested in pleasing the recipient of your largesse. This is why children get underwear at Christmas.

- You spend other people’s money on yourself. You get what you want but price no longer matters. The second wives who ride around with the middle-aged men in the Porsches do this kind of spending at Neiman Marcus.

- You spend other people’s money on other people. And in this case, who gives a [damn]?

Most health-care spending in the U.S. falls into category three. In theory, the people who are funding our expenses — the proverbial middle-aged men in Porsches, except that they’re actually insurance executives and government bureaucrats — have every incentive to step in, cut up the charge cards, and substitute a gift-wrapped box of Hanes briefs with the comfort-soft waistband. In practice, legislators frequently intervene to stop them from exercising much cost-control. The managed care revolution of the 1990s died when patients complained to their representatives, and the representatives ran down to their offices to pass laws making it very hard to deny coverage for anything anyone wanted. Medicare cost-controls, such as the famed Sustainable Growth Rate, fell prey to similar maneuvers. The only system that exhibits sustained cost control is Medicaid, because poor people don’t vote, or exit the system for better insurance.

The result is a system where everyone complains that we spend much too much on health care — and the very same people get indignant if anyone suggests that they, personally, should maybe spend a little bit less. Everyone wants to go to heaven — but nobody wants to die.

Unfortunately, this is what cost-control actually looks like, which is to say, like people not being able to spend as much on health care. Oh, to be sure, we could achieve this end differently — instead of asking patients to pay a modest share of their own costs (the article suggests that this amount is less than 10 percent, in the case of Harvard professors) — we could simply set a schedule of covered treatment, and deny patients access to off-schedule treatments, or even better, not even tell them that those treatments exist. But people don’t like that solution either, which is why medical dramas are filled with rants about insurers who won’t cover procedures, and the law books are filled with regulations that sharply curtail the ability of insurers to ration care. And the third option, refusing to pay top-dollar for care, would be a bit tricky for Harvard to implement, given that they run exactly the sort of high-cost research facilities that help drive health-care costs skyward. Nor do I really think that the angry professors would be mollified by being given a cheap insurance package that wouldn’t let them go see the top-flight specialists their elite status now entitles them to access.

Instead, they persist in our mass delusion: that there is some magic pot of money in the health-care system, which can be painlessly tapped to provide universal coverage without dislocating any of the generous arrangements that insured people currently enjoy. Just as there are no leprechauns, there is no free money at the end of the rainbow; there are patients demanding services, and health-care workers making comfortable livings, who have built their financial lives around the expectation that those incomes will continue. Until we shed this delusion, you can expect a lot of ranting and raving about the hard truths of the real world.

January 3, 2015

Last year, “a Kentucky judge did something no federal judge has done since 1932”

It’s been a very long time since a federal judge in Kentucky anywhere in the United States has struck down a “certificate of necessity” (CON) regulation:

Mighty oaks from little acorns grow, so last year’s most encouraging development in governance might have occurred in February in a U.S. district court in Frankfort, Ky. There, a judge did something no federal judge has done since 1932. By striking down a “certificate of necessity” (CON) regulation, he struck a blow for liberty and against crony capitalism.

Although Raleigh Bruner’s Wildcat Moving company in Lexington is named in celebration of the local religion — University of Kentucky basketball — this did not immunize him from the opposition of companies with which he wished to compete. In 2012, he formed the company, hoping to operate statewide. Kentucky, however, like some other states, requires movers to obtain a CON. Kentucky’s statute says such certificates shall be issued if the applicant is “fit, willing and able properly to perform” moving services — and if he can demonstrate that existing moving services are “inadequate,” and that the proposed service “is or will be required by the present or future public convenience and necessity.”

Applicants must notify their prospective competitors, who can and often do file protests. This frequently requires applicants to hire lawyers for the hearings. There they bear the burden of proving current inadequacies and future necessities. And they usually lose. From 2007 to 2012, 39 Kentucky applications for CONs drew 114 protests — none from the general public, all from moving companies. Only three of the 39 persevered through the hearing gantlet; all three were denied CONs.

Bruner sued, arguing three things: that the CON process violates the Constitution’s equal protection clause because it is a “competitors’ veto” that favors existing companies over prospective rivals; that the statute’s requirements (“inadequate,” “convenience,” “necessity”) are unconstitutionally vague; and that the process violates the 14th Amendment’s protections of Americans’ “privileges or immunities,” including the right to earn a living.

November 19, 2014

November 9, 2014

Rent-seekers and crony capitalists love big government

One of the reasons I’m a small-government fan is that the less the government tries to do, the less opportunity for rent-seekers and crony capitalists to batten on the inevitable opportunities that big government provides when it controls and regulates far beyond its competence:

A nice little point being made over in the New York Times, that for all of the public rhetoric about free markets and competition it’s not actually true that the Republicans are entirely pro-free market and pro-competition at all levels of governance. There’s an explanation for this too, an explanation that comes from the late economist Mancur Olsen. That explanation being about the level of the system that decides what will happen on a particular matter and thus where the special interests will try to capture governance.

Republicans have hailed Uber, the smartphone-based car service, as a symbol of entrepreneurial innovation that could be strangled by misplaced government regulation. In August, the Republican National Committee urged supporters to sign a petition in support of the company, warning that “government officials are trying to block Uber from providing services simply because it’s cutting into the taxi unions’ profits.”

Josh Barro then goes on to point out that while the national Republican party might be saying such fine words when we get down to the people who actually regulate taxi rides then local Republicans can be just as pro-taxis and anti-Uber as any group of Democrats.

[…] More likely, to me at least, is that Mancur Olsen had it exactly right. His point being that over time democracy will end up being a competition between special interests for control of that democratic apparatus. The basic background insight is spread costs and concentrated benefits. One analogy is the pig and the chicken deciding what to have for breakfast. If they decide upon bacon and eggs then the chicken is interested but the pig is rather committed there. So it is with the regulation of producers and the competition that they might faced. US consumers of sugar might be paying $50 a year each to protect US sugar producers (that number’s not right but it’s not far off, it’s not $5 each nor $500) but rationally, when there’s so much else for us to think about, it’s sensible enough for us to not get very excited nor angry about this. But the sugar producers are making millions a year out of that same system of restrictions and subsidies. They’re very interested indeed in making sure that it continues.

We who take taxis or Uber are quite interested in Uber (and Lyft and all the others) being able to continue in business. But it’s not the end of our lifestyle if the regulatory apparatus is able to stifle them. But for the people who, for example, own taxi medallions in NYC then the replacement of the traditional taxi market by Uber will mean the potential loss of up to $1 million for each medallion. They’re very much more interested in crimping Uber’s style than we consumers are in expanding it.

Olsen went on to point out that the special interests are obviously more interested than we are in the details of regulation. And they’ll concentrate their efforts at whatever level of the regulatory and democratic system it is that affects their direct interests. Contributing to election campaigns, making their views known and so on, wheeling and dealing to promote their interests.

September 17, 2014

Creating jobs, good. Creating subsidized jobs, not so good.

Gregg Easterbrook on the difference between ordinary jobs and government subsidized job creation:

Elon Musk Recharges His Bank Account: Tesla’s agreement with Nevada to build a battery factory is expected to create about 6,000 jobs in exchange for $1.25 billion in tax favors. That’s about $208,000 per job. More jobs are always good. But typical Nevada residents with a median household income of $54,000 per year will be taxed to create very expensive jobs for others. Volkswagen is expanding its manufacturing in Tennessee, which is good. But the state has agreed to about $300 million in subsidies for the expansion, which will create about 2,000 jobs — that’s $150,000 per new job, much of the money coming from Tennessee residents who can only dream of autoworkers’ wages. The median household income in Tennessee is $44,140, about a third of the tax subsidies per new Volkswagen job. The Tesla handout was approved by the Democratic state legislature of Nevada; Tennessee’s Republican-controlled state government approved the Volkswagen corporate welfare deal.

At least it’s a bargain compared to federally subsidized solar jobs. A Nevada solar project — state that is home to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, President Barack Obama’s closest ally on Capitol Hill — cost $10.8 million in subsidies per job created. Local public interest groups noticed the extreme subsidy while the national media did not.

This cheeky website monitors giveaways state by state.