Jean-François has two hectares of vines in our valley in South-West France: his family have been making wine here on this hard limestone soil for more than half a century. And yet, he would like nothing more than to grub up his vineyards. If you ask him why, he looks skywards, and then, with hands as gnarled as his vines, pulls out the lining of his coat-pocket. Vide. Empty.

The nectar of the gods, French wines have a reputation for being cultivated in a sun-kissed vineyard surrounding a honey-stoned chateau, owned by a Hollywood star like Leonardo DiCaprio, or a Gallic aristo whose family escaped the guillotine. Jean-François is neither. And he is not the only vigneron who is struggling. Things are far from rosé for France’s small winemakers, as two hundred militants made clear outside the Prefecture in Bordeaux one Thursday last month. They follow the thousand who protested in the city last December, when vignerons hung a human effigy outside the doors of the Bordeaux Wine Council, to raise awareness for grape-growers at risk of suicide. “Every day there is a suicide in agriculture,” Didier Cousiney, president of the Viti 33 collective informed the crowd.

In the Bordeaux area alone, 500 vignerons are looking in the bottom of the glass and seeing financial ruin. And you can add to these the growers nearing retirement who cannot find buyers for their vineyards. Like Jean-François. In the Medoc, land prices are actually sinking.

Jean-François would like to simply abandon his vines. He cannot, because it is illegal. Abandoned vines are vectors for disease, which can spread to other vineyards. Vines must be either cultivated or grubbed up. But grubbing costs €2,000 per hectare, money Jean-François does not have.

Crisis in the French wine industry affects more than viticulteurs. In France, wine is not merely a drink: it’s a national symbol, the liquid affirmation of l’Art de vivre à la française. If you opened the arteries of Marianne, you would find them coursing with a Bordeaux Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée, the official certification for wine grown in the geographical region and made with requisite skill. Until 1981, French children were allowed to drink wine in school. So, when the wine industry turns sour, France’s identity suffers a hangover.

As does its income. Wine is France’s second biggest export after aircraft, worth about €15 billion a year according to the Fédération des Exportateurs de Vins et Spiritueux de France (FEVS).

What’s going wrong in the vineyards of La Belle France? Jean-François’s eloquent gestures indicate some of the causes. Doubtless French winegrowers have been complaining about the weather since the Gauls planted the first native vines in the fifth century BC. But in the last five years, the weather has lurched from one Biblical extreme to another. We’ve had drought, which did for my own few vines last year; we’ve had flooding; we’ve had hailstorms. A late frost in April 2021 affected 80% of the nation’s vineyards.

Such was the desperation of viticulteurs then that vineyards were heated overnight with candles and paraffin heaters, to keep the frost off the delicate buds of the fruit. The sight of the vineyards of Bordeaux, the sacred centre of the French wine industry, lit by geometrically exact lines of candlelight was magnificent, but the image ultimately came to symbolise the powerlessness of humans in the face of Mother Nature. After le gel historique, there were few climate change deniers in Bordeaux’s vineyards. According to the European Environmental Agency, France is suffering the biggest economic losses caused by climate change of any country in the world. The Hexagon took a hit of €4.2 billion in 2020 due to climate change.

John Lewis-Stempel, “The bourgeois war on French wine”, UnHerd, 2023-02-01.

May 17, 2023

QotD: How do you say “Catch-22” en français?

April 16, 2023

Raising the minimum retirement age may be necessary, but it will never be politically popular

As protests and riots continue against the French government’s attempt to raise the minimum retirement age from 62 to 64, Theodore Dalrymple explains why he finds sympathy with the working poor who will be most directly hurt by the change:

Riot police on the streets of Bordeaux as violent protests against French government plans to raise the retirement age continue.

YouTube screen capture from an AFP report.

As I hope to be able to work till my dying day, I am perhaps not the right person to animadvert on the present disturbances in France about the raising of the retirement age from 62 to 64. My work has always been pleasing to me, and it remains so; I even manage to delude myself sometimes that it is important.

I am forced to recognize, however, that not everyone is in the same happy position as I. I am sure that if I had been a dustman all my life, I should not hope to be emptying dustbins at my present age (73), let alone at the age of 85. While my work remains work, and in a certain sense occasionally even hard work, especially when I have to think, what I do is not physically demanding. No one ever got arthritis or fibrosis of the lung by writing a few articles.

The reform of the pension system in France, from my limited understanding of it, is rather unfair. It is true that some reform is necessary: There are ever fewer workers to fund the pensions of ever more pensioners (the system being entirely unfunded by investment). On the other hand, it is those who do the most unpleasant and unremunerative jobs who have to work the longest, and the reform only increases this unfairness. As the old cockney song has it, it’s the rich what gets the pleasure.

Nevertheless, the extreme opposition to the reform, which is hardly a radical one, strikes most foreigners as rather strange. In a way it is also sad, for it implies that a long retirement is the main aim of all that precedes it, which in turn implies that all the work done for several decades before retirement has been an unpleasant imposition rather than something of value in itself. That the quid pro quo for a longer life expectancy is a greater number of years spent working seems not to strike anyone with force.

The demonstrators probably think, no doubt correctly, that the reform is the thin end of a wedge: If it is allowed to pass without a fuss, there will be further such reforms until the retirement age will be 70, 80, or never, depending on life expectancy. As for the younger demonstrators, they do not seem to worry much that it is they who will be paying for the people older than themselves to retire early, the distant prospect of early retirement being more real to them than the far more proximate high rates of taxation.

August 13, 2022

The lure of old wines

In The Critic, Henry Jeffreys admits his continuing love for mature wines, even past the point most people would consider them drinkable:

For some people wine appreciation is like big game hunting. It’s about ticking off the prizes: Latour, Petrus, Romanee Conti. Whereas for others it’s about chasing unicorns, looking for mythical wines so rare that they are almost impossible to obtain. I don’t have the money for either, but even if I did, I still think I would take the greatest pleasure in opening a strange old bottle and being surprised by how delicious it is.

I’m fortunate in having friends and relatives who think wine is more for keeping than for drinking. When my grandfather died, we inherited all kinds of strange things that he’d been saving including a half bottle of 1937 Army & Navy claret.

I’ve certainly never had the deep pockets to go after any of those tip-top wines, although I used to be able to go to LCBO wine tasting events where there’d occasionally be opportunities to try a few ultra-expensive wines (Petrus, Château Margaux, Nuits-Saint-Georges, Chassagne-Montrachet, Puligny-Montrachet, etc.). If I’m totally honest, in a few of those cases, the bouquet of the wine promised far more than the taste could deliver … I appreciate and enjoy better quality wines, but I don’t taste enough difference between a $50 bottle and a $500 bottle to justify paying the premium.

Oddly certain people get quite upset at lovers of very old wine. On Twitter recently a sommelier wrote “your taste sucks” to someone who expressed an enjoyment of such wines.

The French look at this peculiarly British habit as close to necrophilia. Americans, too, drink vintage port after a couple of years rather than waiting a generation as is customary.

There’s something magical about what decades can do to a wine. Quite austere clarets become heady and exotically-spiced while sweet wines begin to taste dry. I also relish the flavours that some might find less appealing: the tang of vinegar, the cooked taste of caramel and the whiff of sherry in wines that definitely are not sherry.

Maybe my taste sucks too but sometimes I prefer a wine to be old than to be particularly good. You adjust your palate, it’s like having a conversation with an elderly relative who’s a bit deaf but with great stories to tell.

March 16, 2021

“… because who doesn’t like to see both wine snobs and the French taken down a peg or two?”

In The Critic, Henry Jeffreys sadly notes the passing of Steven Spurrier, perhaps best known for organizing the “Judgement of Paris” in 1976:

The wine world lost one of its giants this week in Steven Spurrier. He’s one of the very few people who managed to put the subject on the front pages of the world’s newspapers when he organised the so-called Judgement of Paris competition in 1976.

This was a blind tasting judged by the great and good of the French wine world pitting the might of Bordeaux and Burgundy, against California, a place whose wines most Europeans had never even tasted. Surely France could not lose. But thrillingly, and deliciously, it did, with Californian wines coming top in both the white and red categories. It inspired a book and a feature film Bottle Shock starring Alan Rickman as Spurrier. In fact, the media, particularly over here and in the US, has never lost interest. Perhaps because who doesn’t like to see both wine snobs and the French taken down a peg or two?

More significantly, it marked the arrival of American and later Australian, Chilean and other New World wines. Fittingly, I first met Spurrier at a round table tasting for an upmarket Chilean wine. These tastings could be nerve-wracking affairs for new writers. They still fill me with anxiety. I never know what to say as the big beasts of the wine world opine. Sometimes, the cellar rooms where such tastings are often held seem much too small for all those jostling egos.

I was sat next to Spurrier and, much to my surprise, he asked me my opinion on the wines, something I don’t think any other writer had done up to that point. He then engaged with what I said, and said something like, “yes, I think you’ve got it there.” Or words to that effect. It’s quite hard to express how startling this experience was to someone outside the wine world. It’s like Martin Scorsese asking your opinion on film making.

December 15, 2020

Port wine

In The Critic, Henry Jeffreys considers how Port became so popular in Britain:

Before there were package holidays, there was port. This was the way British people shivering on their cold wet island could get a bit of sunshine. It’s a miracle drink, preserving the heat of the Douro valley in liquid form for decades ready to be uncorked and spread cheer. And don’t we need cheer more than ever at the moment? According to Adrian Bridge, CEO of Taylor’s, British port sales were booming during lockdown.

Our love affair with port goes back a long way but the funny thing is that when wines from Portugal began to arrive in large quantities in the 17th century, people hated it. Port was a necessity because Bordeaux, the traditional wine of choice, had become expensive due to the high duty put on it from Cromwell’s time onwards. Early port was a rough sort of wine, often transported down to the city of Oporto in pig skins and adulterated with brandy and elderberries. A poem from 1693 by Richard Ames captures the mood of the times: “But fetch us a pint of any sort, Navarre, Galicia, anything but Port.” The Scots in particular were not impressed. After the Act of Union, wine drinking took on political connotations with Jacobites drinking claret and Hanoverians port. This antipathy to port still persists: a few years back, I sat next to a Scottish woman at dinner who complained that the English only drank port to thumb their noses at Napoleon.

It took a long time before port became the sweet smooth consistent wine that we know and love today. In fact, until 1820 it would usually have been dry. The vintage that year was so hot that the grapes contained more sugar than the yeasts could deal with, so brandy was added while the wines were still fermenting. It was such a success in Britain that this became the model for how port was made in future. Not everyone was keen, however. Baron Forrester, the man who first mapped the course of the Douro river, was still complaining about the new-fangled sweet port right into the 1850s. The current winemaker at Taylor’s, David Guimaraens, reckoned this year’s heatwave had more than a little in common with the 1820 vintage.

Port really is perfectly designed to deal with this heat. Even with modern temperature-controlled fermentation it can be difficult making balanced dry wine with such ripe grapes whereas adding brandy during the fermentation preserves the fresh fruit flavour. Furthermore, heavier wines can be blended with lighter vintages to make tawny ports which are aged for years in wood with oxygen contact. Tawnies were traditionally enjoyed more by the Portuguese but they’re becoming increasingly popular over here. They’re mellow, pale and nutty from oxygen contact, quite different to vintage wines. The great thing is they are ready to drink, no ageing or decanting needed, and an open bottle will last for months. In fact, wood-aged ports are practically indestructible, I’ve had examples from 1937 and 1863 that were both fresh and vigorous.

Grapes with the right balance can go into vintage releases, though a declared vintage from 2020 does look unlikely. The discovery of how well port aged in bottles was probably an accident. A well-off individual would buy a pipe of port (around 500 litres) and have it bottled and corked. It was discovered that after years in bottle, something sublime happened to the fiery tannic wine. A vintage from a declared year will need at least 20 years. Happily, for the impatient among us, ready to drink vintage ports aren’t terribly expensive when you compare with the price of say, mature Bordeaux or Burgundy.

August 6, 2017

The allure of fine wines

Dan Rosenheck recounts his first encounter with one of those mysterious Premier Cru wines:

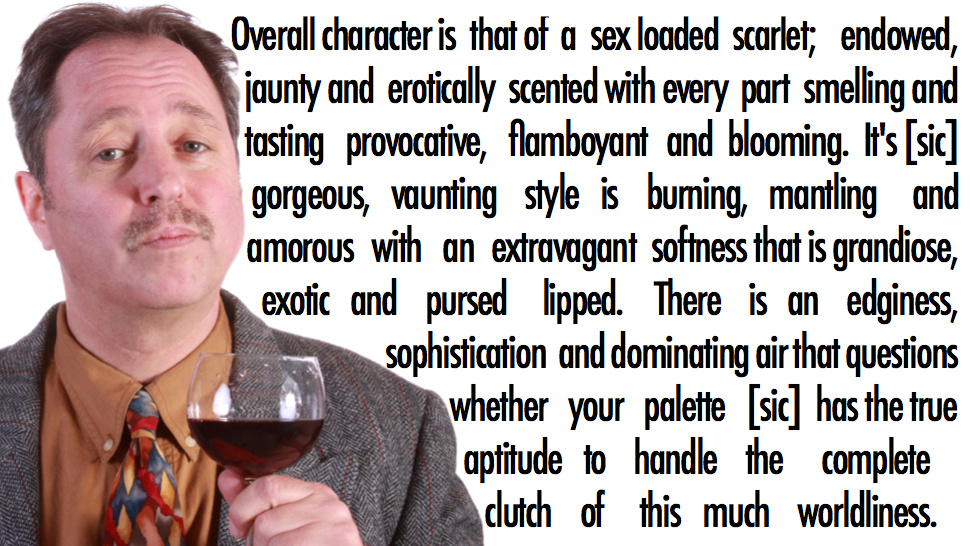

If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. So say those who have never had a whiff of 1998 Château Lafite Rothschild. In late 2011 I had been an aspiring wine connoisseur for about a year, long enough to have learned the names of the world’s most exalted beverages, but not to have tried more than a handful. Like many novices, I started out on Bordeaux, memorising the 1855 classification of the region’s reds into price tiers – called crus, or “growths” – and developing a childlike reverence for the premiers crus (“first growths”) at the top. Although there were no sub-rankings within each class, Lafite was listed first because it was the most expensive tipple in the France of Napoleon III, and my drinking buddies told me it was still considered the premier premier cru today. Chinese drinkers certainly thought so: they had bid it up at auctions to stratospheric heights after deciding, for still-obscure reasons, that Lafite and only Lafite made for an impressive gift – perhaps because its name was easy to pronounce in Mandarin, or because the estate had stuck the character for the lucky number eight on the label of its 2008 vintage.

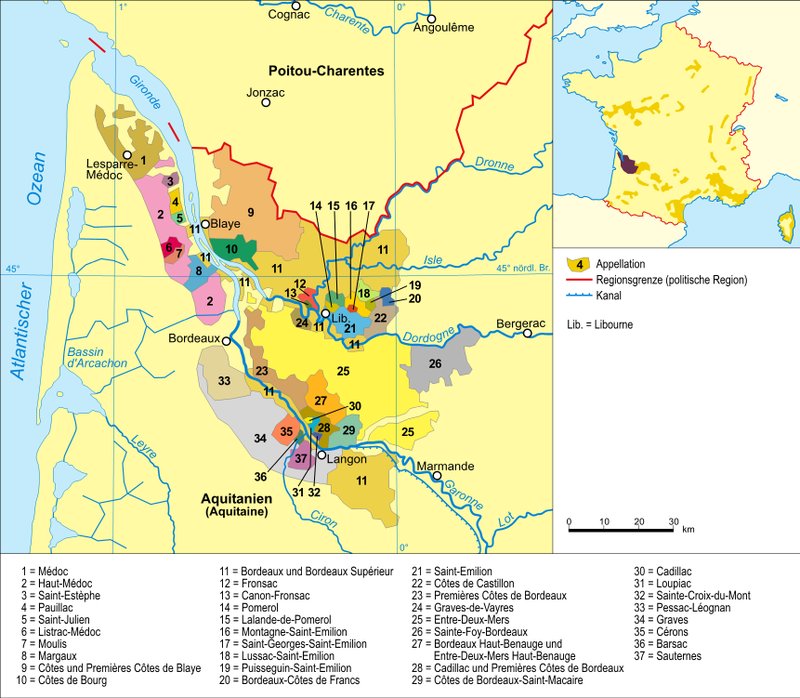

So when a friend in the wine trade snuck me into Wine Spectator magazine’s “Grand Tasting” in New York that November, I made a beeline for the Lafite table. They were pouring the 1998: a middling harvest overall for Cabernet Sauvignon, which Messieurs Primi Inter Pares had nonetheless turned into a masterpiece. As a Frenchwoman doing her best to smile sprinkled her elixir among the parched mob, I made off with a couple of thimblefuls, and scurried to the corner of the room to stand watch over my booty.

The perfume wafted into my nostrils before I had time to lift my glass. “zomfg,” began my tasting note. (The “o”, “m” and “g” stand for “oh my God”, you can guess what the “f” is, and the “z” comes out when exuberance makes you miss the shift key.) The scents were so intense, so focused, so easy to distinguish: ripe blackcurrants quivering on the branch; cedar that conjured up a Lebanese hillside; tobacco or thyme leaves floating on the wind. How could a wine be this powerful and yet this elegant? At the tender age of 13, the 1998 Lafite did not yet offer much complexity, and its firm, astringent tannins left me puckering after every sip – the punishment a fine young Bordeaux inflicts on impatient drinkers who disturb its slumber prematurely. But oh…that smell. “I smelled this across the room,” I wrote. “I smelled this at the bar afterwards. I smelled this even when I was shoving pizza down my throat at 3am. And then I smelled it in my dream.”

My first experience of a premier cru was at an LCBO tasting in downtown Toronto. I had developed an interest in wine a few years before, so I was very excited to try some of the well-known wines for the first time. Here’s what I wrote on the old blog (no longer online) in 2008: “That’s not wine … it’s an ostentatious status symbol”

At some point, an expensive bottle of wine stops being just wine and starts being primarily a status symbol. Case in point:

Staff were delighted at the sale and the three customers were eager to taste the £18,000 magnum of Pétrus 1961 — one of the greatest vintages of one of the greatest wines in the world — which they had reserved from the cellars several weeks before.

Unfortunately, the guests at Zafferano in Knightsbridge proved to be a little too discerning.

As the magnum was uncorked, they declared it to be a fake, refused to touch the bottle and sent it back.

I enjoy wine, and I’m usually able to appreciate the extra quality that goes with a higher price tag … up to a limit. The most expensive wine I’ve tasted was a $400 Chateau Margaux, which was excellent, but (to my taste anyway) not as good as a $95 bottle I sampled on the same evening (a Gevry-Chambertin). Wine is certainly subjective, so my experiences can’t be easily generalized, but I think it would be safe to say that the vast majority of wine drinkers would find that their actual appreciation of the wine tapers off beyond a certain price point.

If you normally drink $15-20 bottles of wine, you’ll certainly find that the $30-40 range will taste better and have more depth and complexity of flavour. Jumping up to the $150-200 range will probably have the same relative effect, but you’ve gone to 10 times the price for perhaps 2-4 times the perceived quality. Perhaps I’m wrong, and the $1,000+ wines have transcendental qualities that peasants like me can’t even imagine, but I strongly doubt it. Any wine over $500 has passed the “quality” level and is from that point onwards really a “prestige” thing.

Update: A commenter at Fark.com offered this link as counter-evidence:

“Contrary to the basic assumptions of economics, several studies have provided behavioral evidence that marketing actions can successfully affect experienced pleasantness by manipulating non-intrinsic attributes of goods. For example, knowledge of a beer’s ingredients and brand can affect reported taste quality, and the reported enjoyment of a film is influenced by expectations about its quality,” the researchers said. “Even more intriguingly, changing the price at which an energy drink is purchased can influence the ability to solve puzzles.”

This is why wines are generally tasted blind for comparative purposes (that is, with no indication of the wine’s identity provided). It’s a well-known phenomena that people expect to enjoy more expensive things than cheaper equivalents.

You can try this one for yourself: next time you’re pouring a beer or a wine for a guest, hide the container and tell them that what you’re pouring is much more rare/expensive/unusual than what it really is. Most people, either from politeness (they don’t want to be rude) or fear of being thought ignorant (that they can’t actually perceive this wonderful quality) or genuine belief in what you’ve said, will go along with the host’s deception and praise the drink as being so much better than whatever they normally drink.

Human beings are wonderful at rationalizing … and self-deception.

H/T to Colby Cosh for the original link.

February 24, 2016

QotD: A lesson from a wine-tasting

Then it was my turn. I was ready to rock the house with a little treasure I wanted to share with the group. I had kept it under wraps until nearly the very end and I was about to BLOW SOME MINDS (well, that was the plan).

First pouring the wine into 18 glasses, I then introduced this secret weapon: a “First Growth” Bordeaux, Chateau Lafite Rothschild 1987. It is the most famous chateau in the world, Benjamin Franklin’s go-to wine, the most collected wine on the planet and the wine most copied for fraudulent gain. People have gone to jail because of this wine! Just read the Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine by Benjamin Wallace, and you will understand the essence of Lafite and why people who can afford it would do anything to get their hands on a bottle. Despite all the mystique and romance of Lafite, it is truly a thrilling wine and I brought a bottle of it to the Yukon, likely the first bottle of Lafite ever consumed in the territory’s vast wilderness.

It was old, a bit tired in fact, but had those mushroom-y, graphite, earthy-fruity notes on the nose that led to a complex palate, now totally integrated, with pretty red fruits, bramble and depth through a silky finish. It was down, but it was not out. At least my mind was blown. But I didn’t hear applause like there was for the rose.

There was just stunned silence, like “what the hell is this?,” until someone finally asked what a bottle of that would cost.

Well, if you could find one at auction, it’s goes under the hammer anywhere from $600 to nearly $1,000 a bottle, according to wine-searcher.com, I said.

More silence. And puzzled, icy stares.

Lee Mennell, a former teacher of mine, an artist and full-time Yukoner living the life in Carcross with his wife and family, finally spoke.

“I don’t really like it. It tastes old.”

It was like a dagger through the heart.

Old? Of course, it’s old. It’s from 1987. It’s Bordeaux, it’s supposed to be old. But, but … don’t you see the beauty and gracefulness in the evolution of the wine? A living, breathing thing that can transform into this grand old dame who can still impress with one sniff, one sip … don’t you see it?

Nope.

It was head-scratching time for me; a reality check, a very important life lesson.

Rick VanSickle, “Buying wine as a gift isn’t rocket science; but sometimes it sure seems like it”, Wines in Niagara, 2016-02-05.

June 7, 2014

“30, 40 or 50 years ago, a year the quality of 2013 Bordeaux would have been a complete disaster”

Even in a good year, I don’t have the money to invest in Bordeaux futures, so I rarely bother to read much about them. Even so, I’d heard that the 2013 vintage was not going to be a good one given the weather that year in the region. The price for Bordeaux wines, however, didn’t do the rational thing and drop below previous (good) years: prices went up. The Wine Cellar Insider explains what happened next:

2013 Bordeaux is not the vintage of the century. The growing season, with its cold, damp character made sure of that. 30, 40 or 50 years ago, a year the quality of 2013 Bordeaux would have been a complete disaster.

But that is not what took place with 2013 Bordeaux. With the willingness to sacrifice quantity for quality, the best producers, with the financial ability to do what needed to be done made some fine wine. 2013 Bordeaux is not an exciting, sexy vintage. But having tasted close to 400 different 2013 Bordeaux wines, clearly, there are some nice wines worth drinking.

So, what’s the problem? When it comes to the wine, none. The average scores from the majority of wine writers and critics show the wines at an average of 89/90 Pts for perhaps the top 100 – 200 wines. Clearly, those are the not the scores for a bad vintage.

[…]

Had the wines been priced in proportion to consumer demand, while 2013 Bordeaux was never going to be an easy sell, it would not have been an impossible sale. I am all for the open, free market when it comes to pricing. Producers can and should price their wine for what they think the market will bear. But 2013 Bordeaux wines remain unsold. Selling the wines to a negociant is not selling the wine. Merchants need to buy and consumers need to purchase as well for it to be a true sale. For some odd reason, in the great vintages, Bordeaux has a knack for pricing the wines correctly. They might seem expensive to mature collectors that are used to paying lower prices, but for the next generation of wine lovers, the wines seem fairly priced.

I get it. On the one hand, due to the excessive unflattering and at times, unfair press, 2013 Bordeaux was never going to receive a warm reception in the marketplace. Perhaps the price the market was actually willing to pay was unappetizing to the chateau owners. But it would have been nice to see an effort. It is difficult for 2013 Bordeaux to sell through to consumers when other recent, and more successful vintages are available in the market for less money.

H/T to Brendan for the link.