The National Post republished a Canadian Press article about a new research paper by Alan Barnes in the Canadian Military History journal:

In the years after the Second World War, Canada developed its ability to prepare strategic intelligence assessments on defence and foreign policy, the paper notes. It would no longer have to rely entirely on assessments from the United States and Britain.

The analytic capability allowed Canada to fully participate in preparing the assessments on the Soviet threat to North America that would underpin joint Canada-U.S. planning for continental defence, Barnes notes.

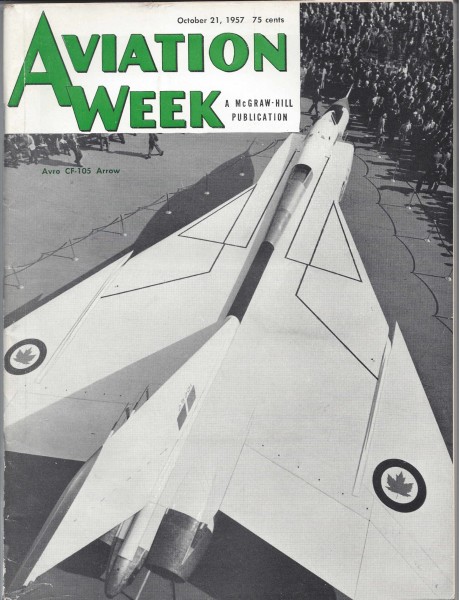

“The CF-100 Canuck, a jet interceptor developed and manufactured in Canada, was just entering service, but there were already concerns that it might soon be outclassed by newer Soviet bombers operating at higher altitudes and faster speeds.”

In November 1952, the Royal Canadian Air Force called for an aircraft with a speed of Mach 2 and the ability to fly at 50,000 feet. “These demanding specifications contributed to the escalating costs and frequent delays in the CF-105 program.”

The Soviets would soon display a new long-range jet bomber, the Bison, at the 1954 May Day parade in Moscow. At an airshow the following year, a fly-past of 28 Bison seemed to indicate that the bomber had entered serial production, two years earlier than predicted, the paper says. In fact, only 18 prototype aircraft participated in the airshow, flying past several times to give the impression of larger numbers.

Even so, this display, along with the appearance of a new Soviet long-range turboprop bomber, the Tu-95 (dubbed the Bear), raised fears that the Soviet Union would soon outnumber the United States in intercontinental bombers, sparking a “Bomber Gap” controversy that figured prominently in American politics, the paper says.

[…]

A January 1958 assessment, “The Threat to North America, 1958-1967”, by Canada’s Joint Intelligence Committee, a co-ordinating body, ultimately had the greatest impact on decisions related to the Arrow, the paper says.

The assessment laid out clear judgments concerning the imminent transition from crewed bombers to ballistic missiles and described the limited size and capabilities of the Soviet bomber force, Barnes notes.

It observed that the Soviet ballistic missiles which were on the verge of being developed were likely to be markedly superior to the foreseeable defences, and concluded that missiles would progressively replace aircraft as the main threat to North America.

The assessment said this meant there would be little justification for the Soviet Union to increase the number of bombers, or to introduce new ones, after 1960.

“The (Joint Intelligence Committee)’s January 1958 assessment was correct in foreseeing Moscow’s shift from bombers to missiles over the subsequent decade,” Barnes writes.

He points out that following the Sputnik launch, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev came to see missiles as a panacea for a range of defence problems and as a cheaper alternative to conventional weapons. “With the Soviet bomber force now looking irrelevant and obsolete, it was relegated to a secondary position in Soviet military thinking.”