Ordinarily, in this space, I try to give some answers. I’m going to try again, in an area in which I am, at least at a technological level, admittedly inexpert. Feel free to argue.

Question 1: Are unmanned aerial drones going to take over from manned combat aircraft?

I am assuming here that at some point in time the total situational awareness package of the drone operator will be sufficient for him to compete or even prevail against a manned aircraft in aerial combat. In other words, the drone operator is going to climb into a cockpit far below ground and the only way he’ll be able to tell he’s not in an aircraft is that he’ll feel no inertia beyond the bare minimum for a touch of realism, to improve his situational awareness, but with no chance of blacking out due to high G maneuvers..

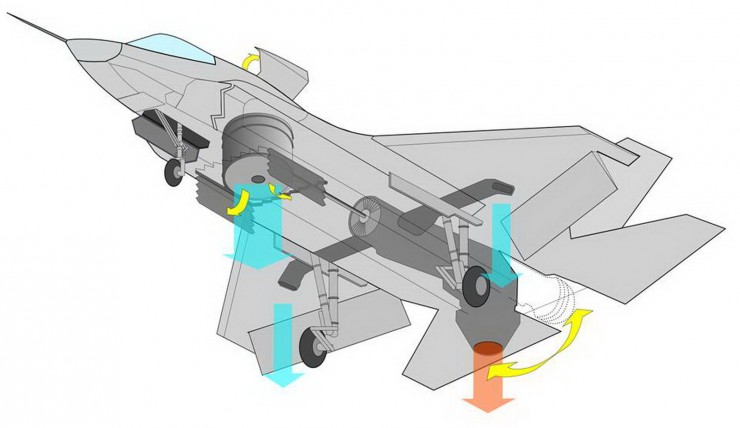

Still, I think the answer to the question is “no,” at least as long as the drones remain under the control of an operator, usually far, far to the rear. Why not? Because to the extent the things are effective they will invite a proportional, or even more than proportional, response to defeat or at least mitigate their effectiveness. That’s just in the nature of war. This is exacerbated by there being at least three or four routes to attack the remote controlled drone. One is by attacking the operator or the base; if the drone is effective enough, it will justify the effort of making those attacks. Yes, he may be bunkered or hidden or both, but he has a signal and a signature, which can probably be found. To the extent the drone is similar in size and support needs to a manned aircraft, that runway and base will be obvious.

The second target of attack is the drone itself. Both of these targets, base/operator and aircraft, are replicated in the vulnerabilities of the manned aircraft, itself and its base. However, the remote controlled drone has an additional vulnerability: the linkage between itself and its operator. Yes, signals can be encrypted. But almost any signal, to include the encryption, can be captured, stored, delayed, amplified, and repeated, while there are practical limits on how frequently the codes can be changed. Almost anything can be jammed. To the extent the drone is dependent on one or another, or all, of the global positioning systems around the world, that signal, too, can be jammed or captured, stored, delayed, amplified and repeated. Moreover, EMP, electro-magnetic pulse, can be generated with devices well short of the nuclear. EMP may not bother people directly, but a purely electronic, remote controlled device will tend to be at least somewhat vulnerable, even if it’s been hardened,

Question 2: Will unmanned aircraft, flown by Artificial Intelligences, take over from manned combat aircraft?

The advantages of the unmanned combat aircraft, however, ranging from immunity to high G forces, to less airframe being required without the need for life support, or, alternatively, for a greater fuel or ordnance load, to expendability, because Unit 278-B356 is no one’s precious little darling, back home, to the same Unit’s invulnerability, so far as I can conceive, to torture-induced propaganda confessions, still argue for the eventual, at least partial, triumph of the self-directing, unmanned, aerial combat aircraft.

Even, so, I’m going to go out on a limb and go with my instincts and one reason. The reason is that I have never yet met an AI for a wargame I couldn’t beat the digital snot out of, while even fairly dumb human opponents can present problems. Coupled with that, my instincts tell me that that the better arrangement is going to be a mix of manned and unmanned, possibly with the manned retaining control of the unmanned until the last second before action.

This presupposes, of course, that we don’t come up with something – quite powerful lasers and/or renunciation of the ban on blinding lasers – to sweep all aircraft from the sky.

Private William Penman, Scots Guards, died 1915 at Le Touret, age 25

Private William Penman, Scots Guards, died 1915 at Le Touret, age 25