Published on 13 Mar 2013

Matt Ridley, author of The Red Queen, Genome, The Rational Optimist and other books, dropped by Reason‘s studio in Los Angeles last month to talk about a curious global trend that is just starting to receive attention. Over the past three decades, our planet has gotten greener!

Even stranger, the greening of the planet in recent decades appears to be happening because of, not despite, our reliance on fossil fuels. While environmentalists often talk about how bad stuff like CO2 causes bad things to happen like global warming, it turns out that the plants aren’t complaining.

September 22, 2014

Reason.tv – Matt Ridley on How Fossil Fuels are Greening the Planet

September 16, 2014

When the “best nutrition advice” is a big, fat lie

Rob Lyons charts the way our governments and healthcare experts got onboard the anti-fat dietary express, to our long-lasting dietary harm:

… in recent years, the advice to eat a low-fat diet has increasingly been called into question. Despite cutting down on fatty foods, the populations of many Western countries have become fatter. If heart-disease mortality has maintained a steady decline, cases of type-2 diabetes have shot up in recent years. Maybe these changes were in spite of the advice to avoid fat. Maybe they were caused by that advice.

The most notable figure in providing the intellectual ammunition to challenge existing health advice has been the US science writer, Gary Taubes. His 2007 book, Good Calories, Bad Calories, became a bestseller, despite containing long discussions on some fairly complex issues to do with biochemistry, nutrition and medicine. The book’s success triggered a heated debate about what really makes us fat and causes chronic disease.

The move to first discussing and then actively encouraging a low-fat diet was largely due to the work of Dr. Ancel Keys, who is to the low-fat diet movement what Karl Marx is to Communism. His energy, drive, and political savvy helped get the US government and the majority of health experts onboard and pushing his advice. A significant problem with this is that Keys’ advocacy was not statistically backed by even his own data. He drew strong conclusions from tiny, unrepresentative samples, yet managed to persuade most doubters that he was right. A more statistically rigorous analysis might well show that the obesity crisis has actually been driven by the crusading health advisors who have been pushing the low-fat diet all this time … or, as I termed it, “our Woody Allen moment“.

Rob Lyons discussed this with Nina Teicholz, author of the book The Big Fat Surprise:

Once the politically astute Keys had packed the nutrition committee of the AHA and got its backing for the advice to avoid saturated fat, the war on meat and dairy could begin. But a major turning point came in 1977 when the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition, led by Democratic senator George McGovern, held hearings on the issue. The result was a set of guidelines, Dietary Goals for the United States [PDF], which promoted the consumption of ‘complex’ carbohydrates, and reductions in the consumption of fat in general and saturated fat in particular.

By 1980, this report had been worked up into government-backed guidelines — around the same time that obesity appears to have taken off in the US. The McGovern Report inspired all the familiar diet advice around the world that we’ve had ever since, and led to major changes in what food manufacturers offered. Out went fat, though unsaturated fat and hydrogenated oils were deemed less bad than saturated fat, so vegetable oils and margarines became more popular. In came more carbohydrate and more sugar, to give those cardboard-like low-fat ‘treats’ some modicum of flavour.

Yet two recent reviews of the evidence around saturated fat — one led by Ronald Krauss, the other by Rajiv Chowdhury — suggest that saturated fat is not the villain it has been painted as. (The latter paper, in particular, sparked outrage.) As for fat in general, Teicholz tells me: ‘There was no effort until very late in the game to provide evidence for the low-fat diet. It was just assumed that that was reasonable because of the caloric benefit you would see from restricting fat.’

Teicholz also debunks the wonderful reputation of the Mediterranean Diet (“a rose-tinted version of reality tailored to the anti-meat prejudices of American researchers”), points out the role of the olive oil industry in pushing the diet (“Swooning researchers were literally wined and dined into going along with promoting the benefits of olive oil”), and points out that we can’t even blame most of the obesity problem on “Big Food”:

Which leads us to an important third point made by Teicholz: that the blame for our current dietary problems cannot solely, or even mainly, be placed at the door of big food corporations. Teicholz writes about how she discovered that ‘the mistakes of nutrition science could not be primarily pinned on the nefarious interests of Big Food. The source of our misguided dietary advice was in some ways more disturbing, since it seems to have been driven by experts at some of our most trusted institutions working towards what they believed to be the public good.’ Once public-health bureaucracies enshrined the dogma that fat is bad for us, ‘the normally self-correcting mechanism of science, which involves constantly challenging one’s own beliefs, was disabled’.

The war on dietary fat is a terrifying example of what happens when politics and bureaucracy mixes with science: provisional conclusions become laws of nature; resources are piled into the official position, creating material as well as intellectual reasons to continue to support it; and any criticism is suppressed or dismissed. As the war on sugar gets into full swing, a reading of The Big Fat Surprise might provide some much-needed humility.

September 13, 2014

QotD: Scrambled eggs

Harris proposed that we should have scrambled eggs for breakfast. He said he would cook them. It seemed, from his account, that he was very good at doing scrambled eggs. He often did them at picnics and when out on yachts. He was quite famous for them. People who had once tasted his scrambled eggs, so we gathered from his conversation, never cared for any other food afterwards, but pined away and died when they could not get them.

It made our mouths water to hear him talk about the things, and we handed him out the stove and the frying-pan and all the eggs that had not smashed and gone over everything in the hamper, and begged him to begin.

He had some trouble in breaking the eggs — or rather not so much trouble in breaking them exactly as in getting them into the frying-pan when broken, and keeping them off his trousers, and preventing them from running up his sleeve; but he fixed some half-a-dozen into the pan at last, and then squatted down by the side of the stove and chivied them about with a fork.

It seemed harassing work, so far as George and I could judge. Whenever he went near the pan he burned himself, and then he would drop everything and dance round the stove, flicking his fingers about and cursing the things. Indeed, every time George and I looked round at him he was sure to be performing this feat. We thought at first that it was a necessary part of the culinary arrangements.

We did not know what scrambled eggs were, and we fancied that it must be some Red Indian or Sandwich Islands sort of dish that required dances and incantations for its proper cooking. Montmorency went and put his nose over it once, and the fat spluttered up and scalded him, and then he began dancing and cursing. Altogether it was one of the most interesting and exciting operations I have ever witnessed. George and I were both quite sorry when it was over.

The result was not altogether the success that Harris had anticipated. There seemed so little to show for the business. Six eggs had gone into the frying-pan, and all that came out was a teaspoonful of burnt and unappetizing looking mess.

Harris said it was the fault of the frying-pan, and thought it would have gone better if we had had a fish-kettle and a gas-stove; and we decided not to attempt the dish again until we had those aids to housekeeping by us.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the dog), 1889.

September 12, 2014

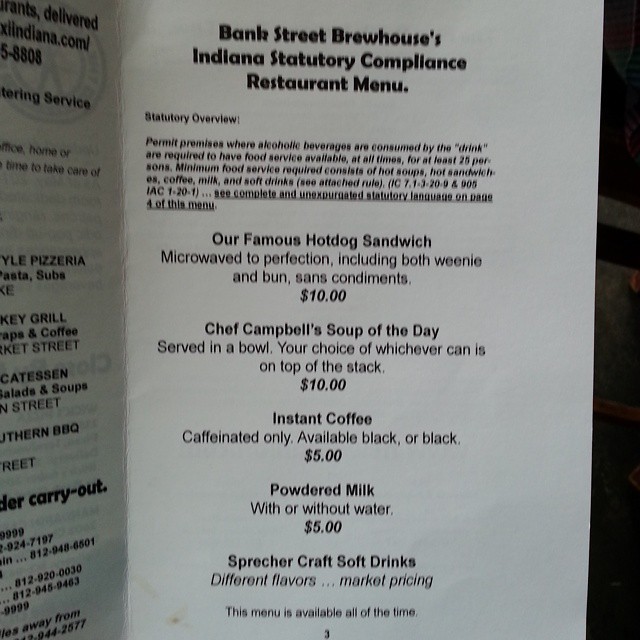

Welcome to Indiana, here is your regulatory compliance brewpub menu

Indiana, like most states, has some odd laws still on the books from the immediate post-Prohibition era, including a “food requirements” rule that specifies that any establishment that serves retail alcoholic beverages must also maintain a restaurant on-site. That restaurant is required to serve certain specific food items. This is how the Bank Street Brewhouse complies with the law:

As you can see, this fully complies with the wording of the rule which requires “a food menu to consist of not less than the following:”

- Hot soups.

- Hot sandwiches.

- Coffee and milk.

- Soft drinks.

H/T to Katherine Mangu-Ward who has more on the ridiculous requirements.

September 6, 2014

Feschuk debriefing – Tim Hortons is not a national treasure

In Maclean’s Scott Feschuk attempts to win the title of “most hated man in Canada” by explaining to Canadians that the Tim Hortons on the corner is not a national shrine:

Have a seat, Canada. Are you comfortable? Good, that’s good.

I noticed you’ve been in a downward spiral since Burger King announced its plan to buy Tim Hortons for $12 billion — or roughly $1 for every Tims on Yonge Street in Toronto.

You’re worried about what the takeover will mean for your morning coffee — and for the corporation that is traditionally depicted in our media as adored, iconic and able to cure hepatitis with its doughnut glaze. (I’m paraphrasing.)

I’m here to help. This is a safe place, Canada. I want to see you get through this. Which is why I need you to listen to me closely. These words will be painful, but it’s important you hear them:

Tim Hortons is not a defining national institution. Rather, it is a chain of thousands of doughnut shops, several of which have working toilets.

Tim Hortons is not an indispensable part of the Canadian experience. Rather, it is a place that sells a breakfast sandwich that tastes like a dishcloth soaked in egg yolk and left out overnight on top of a radiator.

[…]

Canada, you sure do like your double-double — or, as it is by law referred to in news reports, the “beloved double-double.” But here’s a newsflash for you: If you drink your coffee with two creams and two sugars, the quality of the coffee itself is of little consequence. You’d might as well pour a mug of instant coffee or sip the urine of a house cat mixed with a clump of dirt from your golf spikes. It’s all basically the same thing once you bombard it with sweet and dairy. You’re really just wasting your …

I see from your reaction that I’ve crossed a line. I hereby withdraw my defamatory comments about the double-double and kindly ask that you return that handful of my chest hair.

September 2, 2014

The suddenly unsettled science of nutrition

After all the salt uproar over the last year or so, perhaps it was inevitable that other public health consensus items would also come under scrutiny. Here’s Ace having a bit of fun with the latest New York Times report on fat and carbohydrates in the modern diet:

One day there will be a book written about this all — how a “Consensus of Experts” decided, against all previous wisdom and with virtually no evidence whatsoever, that Fat Makes You Fat and you can Eat All the Carbohydrates You Like Because Carbohydrates Are Healthy.

This never made a lick of sense to me, even before I heard of the Atkins diet.

Sugar is a carbohydrate. Indeed, it’s the carbohydrate, the one that makes up the others (such as starches, which are just long lines of sugar molecules arranged into sheets and folded over each other).

How the hell could it possibly be that Fat was Forbidden but SUGAR was Sacred?

It made no sense. A long time ago I tried to get a nutritionist to explain this to me. “Eat more fruit,” the nutritionist said.

“Fruit,” I answered, “is sugar in a ball.”

But the nutritionist had an answer. “That is fruit sugar,” the she told me.

“Fruit sugar,” I responded, “is yet sugar.”

“But it’s not cane sugar.”

“I don’t think the body really cares much about which particular plant the sugar comes from.”

“Sugar from a fruit,” the nutritionist now gambited, “is more natural than processed sugar.”

“They’re both natural, you know. We don’t synthesize sucrose in a lab. There are no beakers involved.”

“Well, you burn fruit sugar up quicker, so it actually gives you energy, instead of turning into fat!”

“Both sugars are converted into glycogen in the body. There can be no difference in how they produce ‘energy’ in the body because both wind up as glycogen. I have no idea where you’re getting any of this. It sounds like you’re making it all up as you go.”

“This is Science,” the nutritionist closed the argument.

Eh. It’s all nonsense. Even cane sugar contains, yes, fructose, or fruit sugar, and fruits contain sucrose, or cane sugar.

August 30, 2014

QotD: We are slaves to our stomachs

How good one feels when one is full — how satisfied with ourselves and with the world! People who have tried it, tell me that a clear conscience makes you very happy and contented; but a full stomach does the business quite as well, and is cheaper, and more easily obtained. One feels so forgiving and generous after a substantial and well-digested meal — so noble-minded, so kindly-hearted.

It is very strange, this domination of our intellect by our digestive organs. We cannot work, we cannot think, unless our stomach wills so. It dictates to us our emotions, our passions. After eggs and bacon, it says, “Work!” After beefsteak and porter, it says, “Sleep!” After a cup of tea (two spoonsful for each cup, and don’t let it stand more than three minutes), it says to the brain, “Now, rise, and show your strength. Be eloquent, and deep, and tender; see, with a clear eye, into Nature and into life; spread your white wings of quivering thought, and soar, a god-like spirit, over the whirling world beneath you, up through long lanes of flaming stars to the gates of eternity!”

After hot muffins, it says, “Be dull and soulless, like a beast of the field — a brainless animal, with listless eye, unlit by any ray of fancy, or of hope, or fear, or love, or life.” And after brandy, taken in sufficient quantity, it says, “Now, come, fool, grin and tumble, that your fellow-men may laugh — drivel in folly, and splutter in senseless sounds, and show what a helpless ninny is poor man whose wit and will are drowned, like kittens, side by side, in half an inch of alcohol.”

We are but the veriest, sorriest slaves of our stomach. Reach not after morality and righteousness, my friends; watch vigilantly your stomach, and diet it with care and judgment. Then virtue and contentment will come and reign within your heart, unsought by any effort of your own; and you will be a good citizen, a loving husband, and a tender father — a noble, pious man.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the dog), 1889.

August 28, 2014

Feeding Tommy Atkins – WW1 food for British troops in the trenches

In the Express last week, Adrian Lee reports on a new exhibit at the Imperial War Museum in London:

They say an army marches on its stomach, so feeding the two million men who were in the trenches at the height of the First World War was some task. It was a great achievement that in the entire conflict not one British soldier starved to death.

Yet no one should think that the Tommies enjoyed the food that was served up by the military. According to the wags on the frontline, the biggest threat to life was not German bullets but the appalling rations.

Most despised was Maconochie, named after the company in Aberdeen that made this concoction of barely recognisable chunks of fatty meat and vegetables in thin gravy.

When served hot, as per the instructions on the tin, it was said to be barely edible. Eaten cold for days on end in the trenches, where a warm meal was usually no more than a fantasy, it was said to be disgusting.

It was the stated aim of the British Army that each soldier should consume 4,000 calories a day. At the frontline, where conditions were frequently appalling, daily rations comprised 9oz of tinned meat (today it would be known as corned beef but during the First World War it was called bully beef) or the hated Maconochie.

Additionally the men received biscuits (made from salt, flour and water and likened by the long-suffering troops to dog biscuits). They were produced under government contract by Huntley & Palmers, which in 1914 was the world’s largest biscuit manufacturer. The notoriously hard biscuits could crack teeth if they were not first soaked in tea or water.

August 26, 2014

Tax inversions: “Canada, it would seem, is the new Delaware”

In Maclean’s, Jason Kirby looks for reasons why Tim Hortons is interested in a deal with Burger King:

For starters, let’s consider Burger King’s motivation for buying Tim Hortons. It is not looking for synergies. Don’t expect to see Burger King roll out twinned stores, with one counter selling Whoppers, the other Timbits, as per Wendy’s strategy when it owned Tims. Instead, Burger King wants to avoid paying U.S. taxes. If the deal goes ahead (no agreement has been finalized) Burger King will achieve this through what’s known as a “tax inversion.” It would buy Tim Hortons, then declare the newly merged company to be Canadian. And because companies in Canada enjoy a lower corporate tax rate than those in America — 15 per cent in Canada compared to an official U.S. rate of 35 per cent — Burger King’s future tax bills could be a lot smaller.

Canada, it would seem, is the new Delaware.

So Burger King is buying Tim Hortons, but in doing so, the combined Tim Hortons and Burger King will be financially engineered to be Canadian, at least on paper. A statement released by the companies following the Wall Street Journal‘s initial report on the deal said Burger King’s largest shareholder, 3G Capital, a Brazilian private equity firm, would own the majority of the shares of the newly created company. And you can be sure any tax savings will flow back to shareholders in the form of higher dividends.

It’s clear what’s driving Burger King to pursue this deal. But there’s been far less attention paid to the question: what’s in this for Tim Hortons?

According to Tim Hortons, the answer — as it unceasingly has been for the past two decades — is the pursuit of international growth. In the statement from Tim Hortons and Burger King, the companies said the coffee chain will have ”the potential to leverage Burger King’s worldwide footprint and experience in global development to accelerate Tim Hortons growth in international markets.”

Update: Kevin Williamson points out that relatively few US companies actually relocate to other countries now, but that the number is clearly increasing and knee-jerk reactions to that by politicians may well make it worse.

There are trillions of dollars in U.S. corporate earnings parked overseas, and progressives want the government to shove its greedy snout all up in that, denouncing “corporate cash hoarders” and blaming un-repatriated corporate earnings for everything from the weak job market to chronic halitosis. Harebrained schemes for putting that corporate cash in government coffers abound. So the current balance could quite easily be tipped. And after years of ad-hocracy under Barack Obama et al., U.S.-style “rule of law” may not be as attractive as it once was. A few more arbitrary NLRB decisions or political jihads from the IRS could change a few minds about the value of U.S. law and governance.

The question isn’t whether you can bully Walgreens out of its plan to move to Switzerland. The question is whether the next Apple or Pfizer ever puts down legal roots in the United States in the first place. Right now, the friction works in favor of the United States, but there is no reason to believe that that will always be the case. You think that Singapore wouldn’t like to be the world’s banking or pharmaceutical capital? That Seoul lacks ambition? That the Scots who brought us the Enlightenment can’t run a decent system of law and property rights? Burger King is not talking about moving to some steamy banana republic for tax purposes, but to stodgy, stable, predictable, boring old Canada. Boring and predictable looks pretty good if you’re Burger King, especially when the alternative is unpredictable and expensive. Unpredictable and expensive is what you date when you’re young and stupid — you don’t marry it.

Update the second:

Golly, I thought we were supposed to admire people who trek northward over the border seeking a better life for their families. #BurgerKing

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) August 26, 2014

August 18, 2014

Salt studies and health outcomes – “all models need to be taken with a pinch of salt”

Colby Cosh linked to this rather interesting BMJ blog post by Richard Lehman, looking at studies of the impact of dietary salt reduction:

601 The usual wisdom about sodium chloride is that the more you take, the higher your blood pressure and hence your cardiovascular risk. We’ll begin, like the NEJM, with the PURE study. This was a massive undertaking. They recruited 102 216 adults from 18 countries and measured their 24 hour sodium and potassium excretion, using a single fasting morning urine specimen, and their blood pressure by using an automated device. In an ideal world, they would have carried on doing this every week for a month or two, but hey, this is still better than anyone has managed before now. Using these single point in time measurements, they found that people with elevated blood pressure seemed to be more sensitive to the effects of the cations sodium and potassium. Higher sodium raised their blood pressure more, and higher potassium lowered it more, than in individuals with normal blood pressure. In fact, if sodium is a cation, potassium should be called a dogion. And what I have described as effects are in fact associations: we cannot really know if they are causal.

612 But now comes the bombshell. In the PURE study, there was no simple linear relationship between sodium intake and the composite outcome of death and major cardiovascular events, over a mean follow-up period of 3.7 years. Quite the contrary, there was a sort of elongated U-shape distribution. The U begins high and is then splayed out: people who excreted less than 3 grams of salt daily were at much the highest risk of death and cardiovascular events. The lowest risk lay between 3 g and 5 g, with a slow and rather flat rise thereafter. On this evidence, trying to achieve a salt intake under 3 g is a bad idea, which will do you more harm than eating as much salt as you like. Moreover, if you eat plenty of potassium as well, you will have plenty of dogion to counter the cation. The true Mediterranean diet wins again. Eat salad and tomatoes with your anchovies, drink wine with your briny olives, sprinkle coarse salt on your grilled fish, lay it on a bed of cucumber, and follow it with ripe figs and apricots. Live long and live happily.

624 It was rather witty, if slightly unkind, of the NEJM to follow these PURE papers with a massive modelling study built on the assumption that sodium increases cardiovascular risk in linear fashion, mediated by blood pressure. Dariush Mozaffarian and his immensely hardworking team must be biting their lips, having trawled through all the data they could find about sodium excretion in 66 countries. They used a reference standard of 2 g sodium a day, assuming this was the point of optimal consumption and lowest risk. But from PURE, we now know it is associated with a higher cardiovascular risk than 13 grams a day. So they should now go through all their data again, having adjusted their statistical software to the observational curves of the PURE study. Even so, I would question the value of modelling studies on this scale: the human race is a complex thing to study, and all models need to be taken with a pinch of salt.

Update: Colby Cosh followed up the original link with this tweet. Ouch!

It remains only to count the number of Canadians flat-out murdered by the Globe and Mail during its incessant, multi-year sodium jihad.

— Colby Cosh (@colbycosh) August 18, 2014

August 10, 2014

QotD: Travelling by sea

A sea trip does you good when you are going to have a couple of months of it, but, for a week, it is wicked.

You start on Monday with the idea implanted in your bosom that you are going to enjoy yourself. You wave an airy adieu to the boys on shore, light your biggest pipe, and swagger about the deck as if you were Captain Cook, Sir Francis Drake, and Christopher Columbus all rolled into one. On Tuesday, you wish you hadn’t come. On Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, you wish you were dead. On Saturday, you are able to swallow a little beef tea, and to sit up on deck, and answer with a wan, sweet smile when kind-hearted people ask you how you feel now. On Sunday, you begin to walk about again, and take solid food. And on Monday morning, as, with your bag and umbrella in your hand, you stand by the gunwale, waiting to step ashore, you begin to thoroughly like it.

I remember my brother-in-law going for a short sea trip once, for the benefit of his health. He took a return berth from London to Liverpool; and when he got to Liverpool, the only thing he was anxious about was to sell that return ticket.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the dog), 1889.

August 6, 2014

QotD: The shame of the American breakfast

It’s a fine summer day, kind and blue. What shall I feel guilty about today? I know! Breakfast.

I had raisin bran. Wonderful, nutritious, unsustainable raisin bran. It was an old box, so most of the plump, unsustainable raisins had moved to the bottom. I also had sliced bananas, to indicate my complicity in global despoliation; juice from oranges whose existence should make me grey with shame; and milk saturated with the moral turpitude of immoral farm practices. And yet I ate it all, washed down with coffee that should have had UNFAIR TRADE stamped on the package, with a picture of Juan Valdez bent under a foreman’s whip.

At least the sausage was high-minded: I slaughtered the hog in the backyard and dressed the carcass, my arms bloody to the elbows; I ground the meat, noting with grim pleasure how the salt of my sweat would spice it. I packed the results into tidy patties, then put it in a box that said JIMMY DEAN and hid it in the grocery-store freezer, where I picked it up later. Really! If anyone asks, that’s my story.

It is necessary to have a qualified defense of your breakfast, because there are people who are annoyed by it. Worried. Angered. YOU HAVE BANANAS. YOU SHOULDN’T HAVE BANANAS.

James Lileks, “The Locavore’s Lament”, National Review, 2014-07-31.

August 3, 2014

NLRB decision would “stick a fork in the franchise model”

In Forbes, Tim Worstall explains why the recent decision by the US government’s National Labour Relations Board could destroy the franchising business model widely used by fast food chains:

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) made a very strange decision last week to rule that McDonald’s the corporation, was a joint employer of the staff in the franchised restaurants. It was, of course, at the urging of those labour activists who would like to union organise in the sector. Dealing with one national company is obviously going to be easier than dealing with thousands of independent business owners. There’s a number of problems with this decision ranging from the way that it overturns what has long thought to be settled law, to it obviating already signed contracts but perhaps the greatest problem is that it calls into question the entire validity of the franchise system.

[…]

The franchisor though gets paid a percentage of pure sales: what the labour costs at the franchises is is no skin off their nose at all. So they’ll not control it. The only major input that the franchisee can control in order to determine profitability would now become, at best, a join venture and we’ve different incentives for each side of the bargain. That’s just not going to work well. I don’t think that Pudzer is being alarmist in stating that this ruling would stick a fork into the franchise model as a whole. You simply can’t have such a system where the franchisees don’t control any of their inputs.

Of course, it’s still open to someone to argue that the franchise system shouldn’t actually exist, that it would be a good thing if everyone were either a truly independent organisation or part of a large and centrally managed group. But if that is the argument that’s being made, or will be made, then it’s a large enough change that it really needs to happen through political means, not administrative law. That means that if Congress wants to change the rules in this manner then that’s up to Congress. But it really shouldn’t be done by the decision of an administrative agency.

August 2, 2014

QotD: Food as “storehouses of embedded knowledge”

It is hard to fathom all of the trial-and-error that has gone into any great cuisine. Imagine how long it must have taken to come up with the idea that food should be cooked in the first place. How many deaths or vomiting sessions stemming from eating spoiled raw meat led to that discovery? How many mistakes were made – and learned from – in the process of aging and curing meats and fish? How many corpses are long since buried and decomposed thanks to someone working out the technical details of food storage? And then there’s the whole wonderful universe of flavor and technique that defines any truly distinctive cuisine. This much salt, that much paprika. Age the cheese this long for this taste, this much longer for that taste. Cuisines are the manifest product of wars, invasions, famines, revolution, religious awakenings, boom times, and scientific breakthroughs. The culinary lessons learned from these momentous times are humbly recorded, without much commentary, in cookbooks. Put it all together and Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking is not merely akin to a time capsule, it’s a memory back-up, an auto-save of a document still being written. At least 99 percent of the things we know are things other people figured out first. Our manners, morals, technology, language, culture come to us on an assembly line that stretches off into prehistory with laborers in animal skins at the front and lab coats at the end.

Even rugged-individualist survivalists living completely alone in the woods somewhere are plugged into a support network of millions of human beings who came before him. Nearly every single thing he does alone in the woods was figured out for him by someone else. He didn’t discover how to start a fire. He probably didn’t forge his own gun or knife, and even if he did, he didn’t learn the techniques for doing so all by himself.

One of the ways we plug into all of this knowledge, how we transfer the data banks of civilization onto the empty barbarian hard drive of humanity, is at the dinner table. We teach our children not to be savages by eating with them and including them in the process of cooking. Food is primal, and by diluting and harnessing the primal urge to eat we start turning barbarians into less-than-barbarians.

Jonah Goldberg, The Goldberg File, 2012-07-13.

July 23, 2014

In statistical studies, the size of the data sample matters

In the ongoing investigation into why Westerners — especially North Americans — became obese, some of the early studies are being reconsidered. For example, I’ve mentioned the name of Dr. Ancel Keys a couple of times recently: he was the champion of the low-fat diet and his work was highly influential in persuading government health authorities to demonize fat in pursuit of better health outcomes. He was so successful as an advocate for this idea that his study became one of the most frequently cited in medical science. A brilliant success … that unfortunately flew far ahead of its statistical evidence:

So Keys had food records, although that coding and summarizing part sounds a little fishy. Then he followed the health of 13,000 men so he could find associations between diet and heart disease. So we can assume he had dietary records for all 13,000 of them, right?

Uh … no. That wouldn’t be the case.

The poster-boys for his hypothesis about dietary fat and heart disease were the men from the Greek island of Crete. They supposedly ate the diet Keys recommended: low-fat, olive oil instead of saturated animal fats and all that, you see. Keys tracked more than 300 middle-aged men from Crete as part of his study population, and lo and behold, few of them suffered heart attacks. Hypothesis supported, case closed.

So guess how many of those 300-plus men were actually surveyed about their eating habits? Go on, guess. I’ll wait …

…

And the answer is: 31.

Yup, 31. And that’s about the size of the dataset from each of the seven countries: somewhere between 25 and 50 men. It’s right there in the paper’s data tables. That’s a ridiculously small number of men to survey if the goal is to accurately compare diets and heart disease in seven countries.

[…]

Getting the picture? Keys followed the health of more than 300 men from Crete. But he only surveyed 31 of them, with one of those surveys taken during the meat-abstinence month of Lent. Oh, and the original seven-day food-recall records weren’t available later, so he swapped in data from an earlier paper. Then to determine fruit and vegetable intake, he used data sheets about food availability in Greece during a four-year period.

And from this mess, he concluded that high-fat diets cause heart attacks and low-fat diets prevent them.

Keep in mind, this is one of the most-cited studies in all of medical science. It’s one of the pillars of the Diet-Heart hypothesis. It helped to convince the USDA, the AHA, doctors, nutritionists, media health writers, your parents, etc., that saturated fat clogs our arteries and kills us, so we all need to be on low-fat diets – even kids.

Yup, Ancel Keys had a tiny one … but he sure managed to screw a lot of people with it.

H/T to Amy Alkon for the link.