Published on 7 Dec 2015

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps or ANZAC fought in Gallipoli, on the Western Front and in the Middle East during World War 1. Even though the Gallipoli campaign was an ultimate failure, it was the birth hour of the New Zealand and Australian national consciousness. Find out how the Great War shaped Australia and New Zealand in our special episode.

December 8, 2015

Born On The Shores Of Gallipoli – ANZAC in WW1I THE GREAT WAR Special

November 15, 2015

Do Australians sound drunk to you?

Lester Haines on how and when the distinctive “Strine” accent originated:

Australians’ distinctive accent – known affectionately as “Strine” – was formed in the country’s early history by drunken settlers’ “alcoholic slur”.

This shock claim, we hasten to add, comes from Down Under publication The Age, which explains:

The Australian alphabet cocktail was spiked by alcohol. Our forefathers regularly got drunk together and through their frequent interactions unknowingly added an alcoholic slur to our national speech patterns.

For the past two centuries, from generation to generation, drunken Aussie-speak continues to be taught by sober parents to their children.

The paper reckons that not only do Aussies speak at “just two thirds capacity – with one third of our articulator muscles always sedentary as if lying on the couch”, but they also ditch entire letters and play slow and loose with vowels.

It elaborates:

Missing consonants can include missing “t”s (Impordant), “l”s (Austraya) and “s”s (yesh), while many of our vowels are lazily transformed into other vowels, especially “a”s to “e”s (stending) and “i”s (New South Wyles) and “i”s to “oi”s (noight).

The upshot of this total disregard for clear English is that our Antipodean cousins are poor communicators and lack rhetorical skills, something which could cost the Australian economy “billions of dollars”, as The Age audaciously quantifies it.

September 23, 2015

Comparative Advantage and the Tragedy of Tasmania (Everyday Economics 4/7)

Published on 24 Jun 2014

What can a small, isolated island economy teach the rest of the world about the nature and causes of the wealth of nations? When Tasmania was cut off from mainland Australia, it experienced the miracle of growth in reverse, as the reduction in trade and human cooperation forced its inhabitants back to the most basic ways of living. In an economy with a greater number of participants trading goods and services, however, there are more ways to find a comparative advantage and earn more by creating the most value for others. Let’s join Bob and Ann as they teach us the “Story of Comparative Advantage” like you’ve never seen it before.

September 18, 2015

The State Of World War 1 – As Reported by A Newspaper 100 Years Ago I THE GREAT WAR – Week 60

Published on 17 Sep 2015

This week Indy dissects a contemporary source from autumn 1915 – the Hobart Mercury newspaper from Australia. You can find the whole newspaper right here: http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/10429329

While the French and British prepare a new offensive on the Western Front, their Entente ally Russia is still suffering in the East when Germany is moving on the last big Russian city of Vilnius. Even though the propaganda says otherwise, the situation for the ANZACs in Gallipoli still looks grim.

August 24, 2015

Comparative Advantage

Published on 25 Feb 2015

What is comparative advantage? And why is it important to trade? This video guides us through a specific example surrounding Tasmania — an island off the coast of Australia that experienced the miracle of growth in reverse. Through this example we show what can happen when a civilization is deprived of trade, and show why trade is essential to economic growth.

In an economy with a greater number of participants trading goods and services, there are more ways to find a comparative advantage and earn more by creating the most value for others. Let’s dive right in with an example from our new friends, Bob and Ann.

August 14, 2015

The Ruse at Gallipoli and the Siege of Kovno I THE GREAT WAR – Week 55

Published on 13 Aug 2015

Another 20.000 soldiers fresh from the barracks are supposed to turn the tide at Gallipoli. But Mustafa Kemal is an Ottoman commander to be reckoned with. With a tactical ruse and the right timing, he surprises the inexperienced ANZAC recruits with a bayonet charge. As the sand of Chunuk Bair turns red, one thing is clear, Gallipoli is still not taken. On the Eastern Front the Germans lay siege on Kovno and are about to encircle the Russian troops near Brest-Litovsk. The German offensive on the Western Front is not nearly as successful though.

May 21, 2015

John Monash – Australia’s greatest general

Strategy Page reviews a new biography of Australia’s General John Monash:

The centennial of the First World War has brought forth renewed public interest and additional scholarly study of that still controversial conflict, variously the last 19th century imperial war and the first modern war. When its great generals are enumerated, one named by relatively few outside the Antipodes is Australian Army Corps commander John Monash (1865-1931), this despite Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery’s declaration half a century after the Armistice that Monash was “the best general on the Western Front in Europe,” and historian Sir Basil Liddell Hart’s even stronger accolade as “the greatest general of World War I by far.” Yet in the three-volume Cambridge History of the First World War, there is not one mention of him.

Monash, it must be said, has not been entirely overlooked. He was knighted in the field by George V (as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath) and subsequently given the title Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, and in his homeland his name graces a university (indeed, the publisher of the book under review), a scholarship, a town and even a freeway. Nevertheless, in Maestro John Monash, former Australian Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer argues that Sir John has been wronged by history and not given his due. In a breezy hagiography (Fischer vehemently denies that characterization, protesting that his biography is “warts and all,” however, he downplays or dismisses most of the “warts” cited, e.g., other generals also had mistresses, and while he made mistakes at Gallipoli, he learned from them) and advocacy piece, he makes a justifiable case for Monash’s posthumous promotion to field marshal (backdated to 1930). Had he been promptly promoted postwar, rather than in 1929, to general (that is, full or four-star general), Fischer points out logically, he likely would have been promoted by the king one step up in rank to field marshal.

In his account of Monash’s life and military career, Fischer details the many obstacles faced and surmounted by “the most innovative general” of the war. His sobriquet for Monash, “maestro,” comes from Sir John’s comparison of a “perfected modern battle plan” to a “score for an orchestral composition.” Indeed, while some British and French generals were still thinking in terms of cavalry charges, sabers and bayonets, drawing on his engineering background, Monash made concerted use of infantry, artillery, tanks, aircraft and radio in (to quote him) “comprehensive holistic battle plan[s].” His strategy’s success became evident in thwarting Germany’s final westward push and smashing through the Hindenburg Line, in the 93-minute Battle of Hamel and the second Battle of Amiens, which German General Ludendorff later called “the black day of the German Army in the war,” victories achieved while Monash was still a lieutenant general (three stars). “Never has a general who did so much to help win a world war … been so unacknowledged,” affirms Fischer, returning to his theme.

May 1, 2015

The Sea Turns Red – Gallipoli Landings I THE GREAT WAR – Week 40

Published on 30 Apr 2015

Completely underestimating the Ottoman army at the Dardanelles, the British commanders decide to let the ANZACs take the Gallipoli peninsular as a gateway to the Bosporus and Constantinople. After the landing in ANZAC Cove and on Z Beach one thing comes clear though: Mustafa Kemal and his troops will fight for every inch of this piece of rock.

April 11, 2015

QotD: Tyranny and the Anglosphere

I’m 41 years old, which doesn’t feel that old to me (most days), but history is short. With the exception of those trapped behind the Iron Curtain, the world as I have known it has been remarkably free and prosperous, and it is getting more free and more prosperous. But it is also a fact that, within my lifetime, there have been dictatorships in Spain, Portugal, Greece, Poland, India, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, South Korea, and half of Germany — and lots of other places, too, to be sure, but you sort of expect them in Cameroon and Russia. If I were only a few years older, I could add France to that list. (You know how you can tell that Charles de Gaulle was a pretty good dictator? He’s almost never described as a “dictator.”) There have been three attempted coups d’état in Spain during my life. Take the span of my father’s life and you’ll find dictatorships and coups and generalissimos rampant in practically every country, even the nice ones, like Norway.

That democratic self-governance is a historical anomaly is easy to forget for those of us in the Anglosphere — we haven’t really endured a dictator since Oliver Cromwell. The United States came close, first under Woodrow Wilson and then during the very long presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. Both men were surrounded by advisers who admired various aspects of authoritarian models then fashionable in Europe. Rexford Tugwell, a key figure in Roosevelt’s so-called brain trust, was particularly keen on the Italian fascist model, which he described as “the cleanest, most efficiently operating piece of social machinery I’ve ever seen.” And the means by which that social hygiene was maintained? “It makes me envious,” he said. That envy will always be with us, which is one of the reasons why progressives work so diligently to undermine the separation of powers, aggrandize the machinery of the state, and stifle criticism of the state. We’ll always have our Hendrik Hertzbergs — but who could say the words “Canadian dictatorship” without laughing a little? As Tom Wolfe put it, “The dark night of fascism is always descending in the United States and yet lands only in Europe.”

Kevin D. Williamson, “The Eternal Dictator: The ruthless exercise of power by strongmen and generalissimos is the natural state of human affairs”, National Review, 2014-06-27.

January 26, 2015

Balancing the art and the science in winemaking

In Cosmos, Andrew Masterson investigates what is still an art and what has been codified as science:

“With commercial yeast you get certainty – you can sleep at night,” says Bicknell. “But how do you make wine more interesting? You exploit the metabolic processes of different yeast species.”

Bicknell’s faith in wild yeasts adds stress at fermentation time, but the pay-off is multi-award-winning wines regularly acknowledged as some of the best in Australia. “The wines do taste different, even if there’s no way you can show that statistically,” Bicknell says. “The only way to really know is to taste.”

Exploiting the diverse and fluctuating populations of wild yeasts found on the plants, fruit and in the air of vineyards is “the new black” (not to mention red and white) in oenology. The practice is becoming more commonplace among artisan winemakers. Even some of the giant commercial wine corporations are investing in the method.

Wild fermentation, says Bicknell, represents the intersection of science, craft and philosophy. But it could also form the basis of a profound shift in the narrative of wine. The more we study winemaking’s microbes, the more it appears they might explain one of the wine industry’s most beloved, but vaguest, terms: terroir.

“Terroir is a wonderful marketing term,” says David Mills, a microbiologist at UC Davis, who studies microbes in wine. “But it’s not a science.”

The French word terroir is difficult to translate. The closest translation is “soil”, but that is just one of its components. Terroir connotes the unique sense of place – the soils, the topography and the microclimate. It’s what makes the wines of Bordeaux or Australia’s Coonawarra so distinctive, and so inimitable.

Sommeliers like Ren Lim, former captain of the Oxford University Blind Tasting Society (and a PhD biophysics student) will tell you merely from swirling a mouthful of Cabernet Sauvignon which Australian winery produced it.

“The ones from Margaret River often give off a more pronounced green pepper note, a note found commonly in Cabernets grown in regions which experience pronounced maritime influences. Coonawarra Cabernets are somewhat different and unique in their own way. They are often minty and have a eucalyptus or menthol note in addition to the usual ripe blackcurrant notes. The green pepper note is often suppressed under the menthol notes. Nonetheless, the Cabernet structure remains in both these wines.”

It’s a feat that Mills does not question. “I don’t doubt regionality exists, but what causes it is a whole other set of issues.”

November 14, 2014

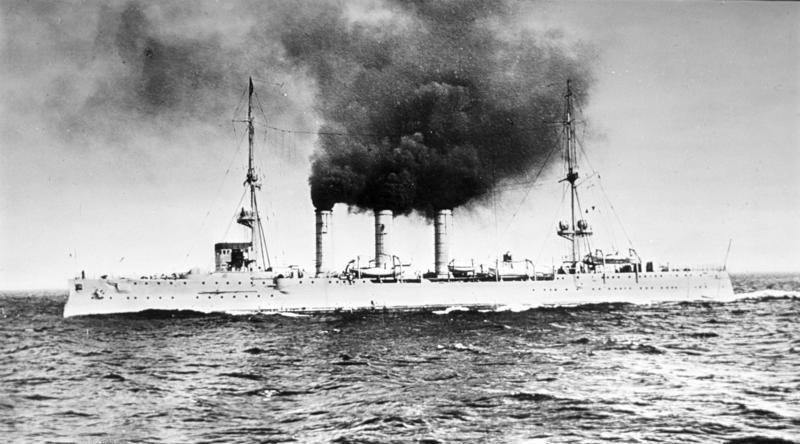

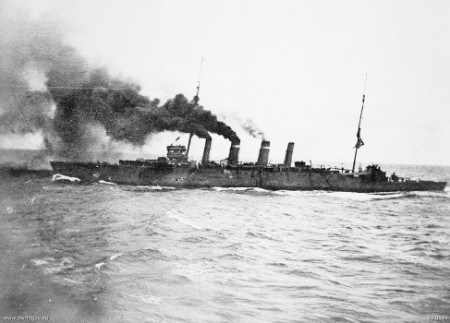

HMAS Sydney versus SMS Emden, 9 November 1914

Last Sunday was the 100th anniversary of the first major naval victory of the Royal Australian Navy, when Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney fought against one of the Kaiser’s most effective commerce raiders, SMS Emden in the Indian Ocean:

November 9 is when the light cruiser HMAS Sydney met the light cruiser SMS Emden in action in the Indian Ocean, dispatching a surface raider that had taken a heavy toll on Allied merchant and naval shipping since the guns of August rang out. R. K. Lochner chronicled Emden’s exploits in the late 1970s, dubbing her “the last gentleman of war.” Lochner awarded the cruiser this title to acknowledge skipper Karl von Müller’s and his crew’s scrupulous fidelity to the laws of cruiser warfare. The Germans’ enemy paid homage to Emden’s gallantry as well. Two days after the engagement, for instance, the London Daily News saluted the “resourceful energy and chivalry” displayed by the raider’s crewmen throughout their voyage. That, of course, was an era when knightly conduct was in decline on the high seas, yielding to unrestricted submarine warfare. Striking without warning, as U-boats commonly did in the Atlantic, left mariners and passengers scant prospects of escaping an attack.

The battle, then, helped mark the passing of an age. Emden had remained behind at the onset of war, after the German East Asian Squadron quit Southeast Asia to return home. Hers was not destined to be a prolonged cruise. Cut off from logistical and maintenance support, Captain Müller had to forage for coal and stores. The cruiser coped with this hand-to-mouth existence — for a while — and in the process sank or captured twenty-five merchantmen, destroyed two Allied men-of-war at Penang, and bombarded the seaport of Madras, along the seacoast of British India. That’s quite a combat record. It’s especially noteworthy when compiled by seafarers who were unsure where they could refuel next — if anywhere at all — and were sure that equipment that suffered a major breakdown would never be repaired for want of spare parts and shipyard expertise.

The light cruiser HMAS Sydney steams towards Rabaul. The Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF), which included HMAS Sydney, HMAS Australia, HMAS Encounter, HMAS Warrego, HMAS Yarra and HMAS Parramatta, seized control of German New Guinea on 11 September 1914 (via Wikipedia)

No ship can keep going for long without putting into port or tapping resources from nearby fuel or stores ships. Heck, U.S. Navy commanders — like their counterparts in other fleets, no doubt — get antsy when the fuel tanks drop to half-empty or hardware fails at sea, hampering performance or reducing redundancy in the propulsion plant or other critical machinery. And that’s in a navy accustomed to having logistics vessels steaming in company to top off the tanks, replenish stores, or transfer or manufacture spares when need be. Imagine being altogether alone in some faraway region — at risk of running out of some vital commodity or suffering battle damage and finding yourself dead in the water. Such loneliness and doubt were constant companions to Emden officers and men during the fall of 1914.It takes extraordinary pluck to seize the offensive amid such circumstances. And yet the Germans did. In November, nonetheless, Sydney found Emden in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, where Müller had decided to attack a communications station that was aiding the hunt for his raider. Like so many naval actions, it was a chance encounter. The station got off a distress call, and Sydney — which happened to be in the vicinity while helping escort a convoy transporting Australian and New Zealand troops to Europe — responded to it. Emden gave a good account of herself, landing several punches before Sydney’s heavier main guns began to tell. Hopelessly outgunned, Müller ultimately ordered his vessel beached on North Keeling Island to save lives. Of the crew, 134 seamen fell while 69 were wounded and 157 were captured.

September 14, 2014

Australia’s search for new submarines

A few days ago, news reports indicated that the next generation of submarines for the Royal Australian Navy would be bought from Japan, rather than built in Australia. Kym Bergmann says the reports are probably misleading:

There has been a flurry of public commentary following yesterday’s News Limited claims that Australia is about to enter into a commitment to buy its next generation of submarines from Japan. The local submarine community has been concerned about that possibility for some time, and senior members of the Submarine Institute of Australia have been writing to Defence Minister David Johnston — and others — since January of this year warning against such a decision.

Understanding what’s happening is difficult because the speculation appears based on remarks apparently made by Prime Minister Tony Abbott to his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe about such a course of action. The concerns have been reinforced among some observers by Abbott’s interest in strengthening Australia–Japan–U.S. defense ties — something in turn being driven by the rise of China. Yesterday Prime Minister Abbott did nothing to dampen the speculation, stating that future submarines were about capability, not about local jobs. As an aside, those sorts of comments also serve the PM’s aggressive political style, jabbing a finger into the eye of the current South Australian Labor Government.

However, the chances of the Federal Government making a unilateral decision to sole source a Japanese solution seem low — and if the Prime Minister were to insist on that particular course of action there could be a serious Cabinet and back bench revolt. Not only would such a decision constitute another broken promise — the word “another” would presumably be contested by the PM on the basis that no promises have been broken to date — but it’d almost certainly lead to the loss of Federal seats in South Australia (Hindmarsh for sure, perhaps Boothby and Sturt), as well as generate enormous resentment within institutions no less than the Royal Australian Navy, the Department of Defence, trade unions and a stack of industry associations, amongst others.

Australia is similar to Canada in this regard: military expenditure is almost always seen as regional development/job creation/political vote-buying first and value-for-money or ensuring that the armed forces have the right kit for the task come a very distant second. This means that the RAN, like the RCN, often ends up with fewer hulls sporting lower capabilities for much more money than if they were able to just buy the best equipment for their needs whether overseas or at home. But that doesn’t get the government votes in “key constituencies”, so let the sailors suffer if it means shoring up support in the next federal election…

July 29, 2014

Australia’s bitter experience with carbon mitigation

Shikha Dalmia looks at Australia’s recently abandoned carbon tax scheme:

Environmentalists had a global meltdown last week after Australia scrapped its carbon tax. They denounced the move as “retrograde” and “environmental vandalism.”

They can fume all they want, but Australia’s action, combined with Europe’s floundering cap-and-trade program, signals that “mitigation” strategies — curbing greenhouse gases by putting economies on an energy diet — are not winning or workable.

Australia leapfrogged from being an environmental laggard (initially refusing to even sign the Kyoto Protocol) to a leader when its Green Party-backed Labor prime minister imposed a tax two years ago. It required Australia’s utilities and industries to pay $23 per ton of greenhouse gas emissions.

But the tax was an instant debacle.

Australia has the highest per capita carbon dioxide emission in the world and the main reason is that it’s even more coal-dependent than America. Coal supplies 75 percent of its energy needs (compared to 42 percent in America). But contrary to green expectations, the tax didn’t prompt companies to rush toward renewable sources, because they are far costlier.

Rather, utilities passed their costs to households — whose energy bills soared by 20 percent in the first year. Other industries that face hyper-competitive environment such as airlines suffered massive losses. (Virgin Australia alone reported $27 million in losses in just six months.) The tax also made Australian exports globally uncompetitive, deepening the country’s recession.

This spawned a backlash that brought down the Labor government and catapulted into office the Liberal Party’s Tony Abbott, who made a “blood promise” to ditch the tax, which he did promptly once elected, despite warnings that Aussie lowlands are more vulnerable to rising sea levels and other dire consequences of global warming than other countries.

June 25, 2014

June 9, 2014

Australia gets sensible about military shipbuilding

Australia has similar military issues to the ones Canada faces, but unlike our own government (who view military spending primarily as the regional economic development variant of crony capitalism), Australia is amenable to economic sense when it comes to building the new support ships for the Royal Australian Navy:

The RAN is about to bring 3 large Hobart Class destroyers into service, but it’s the new LPD HMAS Choules and 2 Canberra Class 27,500t LHD amphibious assault ships that are going to put a real strain on the RAN’s support fleet. Liberal Party defense minister Sen. Johnson didn’t mince words when he announced the competition, early in their governing term:

“With the large LHD’s [sic] – 28,000 tonnes each – we must have a suitable replenishment ship to supply and support those vessels going forward, the planning for this should have been done a long, long time ago.”

The Australian government is explicit about needing “fuel, aviation fuel, supplies, provisions and munitions on these ships,” and they’ve short-listed 2 main competitors to build the ships outside of Australia:

Cantabria Class. The Cantabrias are an enlarged 19,500t version of the Patino Class replenishment ship. Fuel capacity rises to 8,920 m3 ship fuel and 1,585 m3 of JP-5 naval aviation fuel. Throw in 470t of general cargo, 280t of secured ammunition, and 215 m3 of fresh water to round out its wet/dry capabilities. These ships also carry a crew medical center with 10 beds, including operating facilities equipped for telemedicine by videoconference, an X-ray room, dental surgery, sterilization laboratory, and gas containment.Spain already uses this ship type, and Navantia S.A. is already building the Hobart Class and Canberra Class, giving them a deep relationship with Australian industry and the Navy.

Aegir Class. The government named Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (DSME), who are currently building Britain’s MARS 37,000t oiler/support ships based on BMT’s Aegir design. The concept is scalable, and Australia’s government sized the variant they’ve shortlisted at around 26,000t. BMT’s Aegir 26 design offers up to 19,000 m3 of cargo fuel, and 2-5 replenishment at sea stations for hoses and transfer lines. The design itself is somewhat customizable, so it will be interesting to see what the offer’s final specifications and features are.

Recall that HMAS Sirius was also built in South Korea, albeit in a different dockyard. That isn’t surprising, because South Korea arguably has the world’s best shipbuilding industry. Norway and Britain have each purchased customized versions of the Aegir Class ships.

Both the Royal Navy and the Royal Australian Navy are willing to buy ships from Korea. Why not the Royal Canadian Navy’s next ships? Because the government would rather spend many times more money and get smaller, less capable ships as long as they get to spread the money around to cronies:

They won’t be built in Australia, because the government doesn’t believe that the industrial infrastructure and experience is in place to build 20,000+ tonne ships locally. Britain has made a similar calculation, while Canada provides a cautionary example by building smaller supply ships locally at over 5x Britain’s cost.

H/T to Mark Collins for the link. Mark also posted this back in 2013:

To add insult to injury, the Royal Fleet Auxiliary, the civilian-manned support ships for the Royal Navy, are purchasing 4 replenishment vessels under the MARS tanker program to be built in South Korea by Daewoo (arguably the foremost shipbuilder in the world). These ships are slightly larger than the Berlin-class. What is the British government paying for these 4 vessels? £452M or about $686M USD. Not per ship but for all four. The per unit cost is around $170M. If we somehow manage to keep the cost for the JSS at $1.3B per unit, that will still be over 7.5x what the British are paying. If the cost goes up to ~$2B per JSS, we’re looking at almost 12x the cost [though the RCN’s JSS is supposed to have some additional capabilities (already much reduced from 2006 to now, and see the very optimistic timeline here) — but how many of them can the government afford?].