Published on 23 May 2015

Shaka sought vengeance for Dingiswayo on Zwide and the Ndwandwe. He expanded his control over the Mtethwa and other tribes, then launched his assault on the Ndwandwe. Shaka scored two crushing victories over the course of an eighteen month war, although Zwide escaped both times. Shaka invaded the main Ndwandwe village, capturing Zwide’s mother and burning her to death in place of her son. Shaka had won the war, but the people he pushed out created a ripple of instability across Africa: the Mfecane or the Crushing. Shaka himself became dangerously disturbed when his mother died and he began to take his grief out on his people. His brothers assassinated him to take the throne, leading to a new king: Dingane. Dingane began to treat with the Dutch colonists in South Africa, but what began as a friendly relationship became a betrayal when he turned on them. Dingane attacked their wagon train at the Battle of Bloody River, but the Dutch with their guns held him off. The Dutch then threw their support behind Dingane’s last surviving brother, Mpande, who successfully overthrew him and became the new Zulu king.

June 15, 2015

Africa – Zulu Empire II – The Wrath of Shaka Zulu – Extra History

June 14, 2015

Africa: Zulu Empire I – Shaka Zulu Becomes King – Extra History

Published on 16 May 2015

With no written records from the Zulus themselves, historians and anthropologists have pieced together their history from a smattering of sources. We first learn of the Zulu as a minor tribe of the Bantu people, living in South Africa. Shaka Zulu, the man who would organize them into an empire, was born the illegitimate son of a Zulu king. He was sent away with his mother Nandi to grow up in her tribe, the Langeni, but he eventually caught the attention of Dingiswayo, the leader of another powerful tribe called the Mtethwa. Appointed as the leader of a squadron called an ibutho, Shaka developed new tactics including a short “iklwa” fighting spear and a simple but effective military maneuever called “the Bull Horn.” When his father died, Shaka – now a successful military leader – returned with Dingiswayo’s backing to assassinate the rightful heir and assume control of his native tribe. Just a year later, though, the neighboring Ndwandwe tribe murdered Dingiswayo and Shaka vowed revenge on their leader, Zwide. He then launched a bloody war that, combined with the strains created by European colonization, led to the Mefacane, or the Crushing.

June 13, 2015

South Africa in WW1 I THE GREAT WAR Special feat. Extra Credits

Published on 6 Jun 2015

Check out the Extra Credits Series on the native history of South Africa right here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZLGK…

The history of South Africa was already influenced by ethnic tension between the natives and the recently arrived colonists from Great Britain and the Netherlands. The Boers had actually fought to wars with the Empire for self determination. Still, in World War 1 they fought for the King. South Africa saw major action in German East Africa against Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. But their troops were tested in Europe as well. For example in Delville Woods too where they fiercely fought agains the attacking German Army.

May 15, 2015

Artillery Crisis on the Western Front – The Fall of Windhoek I THE GREAT WAR Week 42

Published on 14 May 2015

The 2nd Battle of Ypres is still going but no side can gain a decisive advantage. The main reason on the British side is a lack of artillery ammunition. Even the delivered shells are not working correctly. But even the German supply lines are stretched thin. At the same time German South-West Africa falls to South African troops under Louis Botha.

February 21, 2015

“… could stand to read” some history

Mark Steyn has read some history:

Before the civil war, Beirut was known as “the Paris of the east”. Then things got worse. As worse and worser as they got, however, it was not in-your-face genocidal, with regular global broadcasts of mass beheadings and live immolations. In that sense, the salient difference between Lebanon then and ISIS now is the mainstreaming of depravity. Which is why the analogies don’t apply. We are moving into a world of horrors beyond analogy.

A lot of things have gotten worse. If Beirut is no longer the Paris of the east, Paris is looking a lot like the Beirut of the west — with regular, violent, murderous sectarian attacks accepted as a feature of daily life. In such a world, we could all “stand to read” a little more history. But in Nigeria, when you’re in the middle of history class, Boko Haram kick the door down, seize you and your fellow schoolgirls and sell you into sex slavery. Boko Haram “could stand to read” a little history, but their very name comes from a corruption of the word “book” — as in “books are forbidden”, reading is forbidden, learning is forbidden, history is forbidden.

Well, Nigeria… Wild and crazy country, right? Oh, I don’t know. A half-century ago, it lived under English Common Law, more or less. In 1960 Chief Nnamdi Azikiwe, second Governor-General of an independent Nigeria, was the first Nigerian to be appointed to the Queen’s Privy Counsel. It wasn’t Surrey, but it wasn’t savagery.

Like Lebanon, Nigeria got worse, and it’s getting worser. That’s true of a lot of places. In the Middle East, once functioning states — whether dictatorial or reasonably benign — are imploding. In Yemen, the US has just abandoned its third embassy in the region. According to the President of Tunisia, one third of the population of Libya has fled to Tunisia. That’s two million people. According to the UN, just shy of four million Syrians have fled to Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and beyond. In Iraq, Christians and other minorities are forming militias because they don’t have anywhere to flee (Syria? Saudia Arabia?) and their menfolk are facing extermination and their women gang-rapes and slavery.

These people “could stand to read” a little history, too. But they don’t have time to read history because they’re too busy living it: the disintegration of post-World War Two Libya; the erasure of the Anglo-French Arabian carve-up; the extinction of some of the oldest Christian communities on earth; the metastasizing of a new, very 21st-century evil combining some of the oldest barbarisms with a cutting-edge social-media search-engine optimization strategy.

February 12, 2015

EU governments and GM crops

Last month, Matt Ridley ran down the benefits to farmers, consumers, ecologists and the environment itself that the European Union has been resisting mightily all these years:

Scientifically, the argument over GM crops is as good as over. With nearly half a billion acres growing GM crops worldwide, the facts are in. Biotech crops are on average safer, cheaper and better for the environment than conventional crops. Their benefits accrue disproportionately to farmers in poor countries. The best evidence comes in the form of a “meta-analysis” — a study of studies — carried out by two scientists at Göttingen University, in Germany.

The strength of such an analysis is that it avoids cherry-picking and anecdotal evidence. It found that GM crops have reduced the quantity of pesticide used by farmers by an average of 37 per cent and increased crop yields by 22 per cent. The greatest gains in yield and profit were in the developing world.

If Europe had adopted these crops 15 years ago: rape farmers would be spraying far less pyrethroid or neo-nicotinoid insecticides to control flea beetles, so there would be far less risk to bees; potato farmers would not need to be spraying fungicides up to 15 times a year to control blight; and wheat farmers would not be facing stagnant yields and increasing pesticide resistance among aphids, meaning farmland bird numbers would be up.

Oh, and all that nonsense about GM crops giving control of seeds to big American companies? The patent on the first GM crops has just expired, so you can grow them from your own seed if you prefer and, anyway, conventionally bred varieties are also controlled for a period by those who produce them.

African farmers have been mostly denied genetically modified crops by the machinations of the churches and the greens, aided by the European Union’s demand that imports not be transgenically improved. Otherwise, African farmers would now be better able to combat drought, pests, vitamin deficiency and toxic contamination, while not having to buy so many sprays and risk their lives applying them.

I made this point recently to a charity that works with farmers in Africa and does not oppose GM crops but has so far not dared say so. Put your head above the parapet, I urged. We cannot do that, they replied, because we have to work with other, bigger green charities and they would punish us mercilessly if we broke ranks. Is the bullying really that bad? Yes, they replied.

Yet the Green Blob realises that it has made a mistake here. Not a financial mistake — it made a fortune out of donations during the heyday of stoking alarm about GM crops in the late 1990s — but the realisation that all it has achieved is to prolong the use of sprays and delay the retreat of hunger.

January 28, 2015

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

Published on 26 Jan 2015

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, also known as the Lion of Africa, was commander of the German colonial troops in German East Africa during World War 1. His guerilla tactics used againd several world powers of the time are considered to be one of the most successful military missions of the whole war. In Germany, he was celebrated as a hero until recently. But recent historical research show a picture much more controversial than the one of a glorious hero.

December 4, 2014

“Hiram Maxim’s business was secure”

Paul Richard Huard has another in his series of blog posts on the weapons of the 20th century:

During the early morning of Oct. 25, 1893, a column of 700 soldiers from the British South African Police camped in a defensive position next to the Shangani River.

While they slept, the Matabele king Lobengula ordered an attack on the column, sending a force of up to 6,000 men — some armed with spears, but many with Martini-Henry rifles.

Among its weapons, the column possessed several Maxim machine guns. Once a bugler sounded the alert, the Maxims spun into action — and the results were horrific.

The Maxim gunners mowed down more than 1,600 of the attacking Matabele tribesman. As for the British column, it suffered four casualties.

The British military not only measured the Maxim gun’s success by the number of Matabele killed in action. They could gauge the Maxim’s potential as a weapon of psychological warfare.

In the aftermath, several Matabele war leaders committed suicide either by hanging themselves or throwing themselves on their spears. That is how Earth-shattering a weapon the Maxim gun was.

“The round numbers are suspicious,” C.J. Chivers wrote in The Gun, his history of automatic weapons. “But the larger point is unmistakable. A few hundred men with a few Maxims had subdued a king and his army, and destroyed the enemy’s ranks. Hiram Maxim’s business was secure.”

A British Maxim gun section that took part in the Chitral Relief Expedition of 1895. Public domain photo

November 30, 2014

Bad politics, bad economics and the “great chocolate shortage”

Tim Worstall explains that the fuss and bother in European newspapers about the “market failure” in the chocolate supply is actually a governmental failure (a market sufficiently bothered by legislation and regulation):

The last few days have seen us regaled with a series of stories about how the world is going to run out of chocolate. That would be, I think we can all agree, almost as bad as running out of bacon. So it’s worth thinking through the reasons as to why we might be running out. After all, cocoa, from which chocolate is made, is a plant, it’s obviously renewable in that it grows each season. So how can we be running out of something we farm? The answer is, in part at least, that there’s some bad public policy at the root of this. As there usually is when something that shouldn’t happen does.

Here’s the basic story in a nutshell:

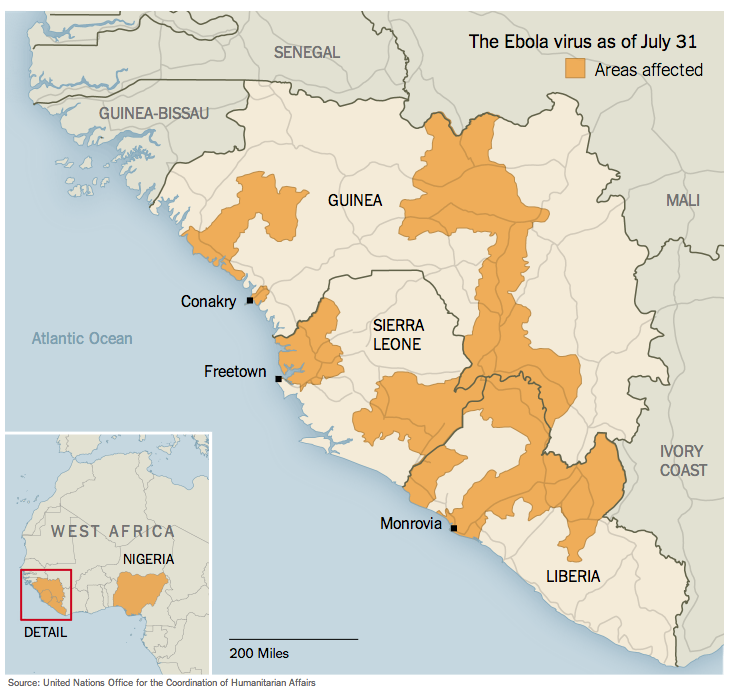

A recent chocolate shortage has seen cocoa farmers unable to keep up with the public’s insatiable appetite for the treat–and the world’s largest chocolate producers, drought, Ebola and a fungal disease may all be to blame.

Much of the world’s chocolate comes from West Africa so the disruption by the Ebola outbreak is one obvious part of it. But the shortage is not something immediate, it’s something that has been coming for some years. Ebola is right now, not a medium term influence. Drought similarly, that’s a short term thing, and this is a medium term problem. It’s also true that as the world gets richer more people can afford and thus desire that delicious chocolate.

[…]

Ahhh…the government is paying the farmers £1 a kg or so and the market is indicating that supply and demand will balance at £1.88 a kg. So, what we’ve actually got here is some price fixing. And the price to the producers is fixed well below the market clearing price (although the government most certainly gets that market price). So, we’ve a wedge in between the prices that consumers are willing to pay for a certain volume and the price that the farmers get for production. So, therefore, instead of it being the price that balances supply and demand we end up with an imbalance of the supply and demand as a result of the price fixing.

This is how it always goes, of course, whenever anyone tries to fix a price. If that price is fixed above the market clearing one then producers make more than anyone wants to consume (think the EU and agriculture, leading to butter mountains and wine lakes). If the price is fixed below the market clearing one then producers don’t make as much as people want to consume. This is why it’s near impossible to get an apartment anywhere where there is rent control. And if prices are fixed at the market clearing price then why bother in the first place? Quite apart from the fact that we’ve got to use the market itself to calculate the market clearing price.

November 22, 2014

What Thucydides can teach us about fighting ebola

In The Diplomat, James R. Holmes says that we can learn a lot about fighting infectious diseases like ebola by reading what Thucidides wrote about the plague that struck Athens during the opening stages of the Peloponnesian War:

Two panelists from our new partner institution, a pair of Africa hands, offered some striking reflections on the fight against Ebola.

Their presentations put in me in the mind of … classical Greece. Why? Mainly because of Thucydides. Thucydides’ history of the Peloponnesian War isn’t just a (partly) eyewitness account of a bloodletting from antiquity; it’s the Good Book of politics and strategy. Undergraduates at Georgia used to look skeptical when I told them they could learn ninety percent of what they needed to know about bareknuckles competition from Thucydides. The remainder? Technology, tactics, and other ephemera. Thucydides remains a go-to source on the human factor in diplomacy and warfare.

But I digress. Ancient Greece suffered its own Ebola outbreak, a mysterious plague that struck Athens oversea during the early stages of the conflict. And the malady struck, perchance, at precisely the worst moment for Athens, after “first citizen” Pericles had arranged for the entire populace of Attica, the Athenian hinterland, to withdraw within the city walls. The idea was to hold the fearsome Spartan infantry at bay with fixed fortifications while the Athenian navy raided around the perimeter of the Spartan alliance.

[…]

That’s where the parallel between then and now becomes poignant. Thucydides notes, for example, that doctors died “most thickly” from the plague. The Brown presenters noted that, likewise, public-health workers in Africa — doctors, nurses, stretcher-bearers — are among the few to deliberately make close contact with the stricken. Relief teams, consequently, take extravagant precautions to quarantine the disease within makeshift facilities while shielding themselves from contagion. Sometimes these measures fail.

Now as in ancient Greece, furthermore, the prospect of disease and death deters some would-be healers altogether from succoring the afflicted. Selflessness has limits. Some understandably remain aloof — today as in Athens of yesteryear.

Teams assigned to bury the slain also find themselves in dire peril. Perversely, the dead from Ebola are more contagious than living hosts. That makes disposing of bodies in sanitary fashion a top priority. As the plague ravaged Athens, similarly, corpses piled up in the streets. No one would perform funeral rites — even in this deeply religious society. Classicist Victor Davis Hanson ascribes some of Athens’ barbarous practices late in the war — such as cutting off the hands of captured enemy seamen to keep them from returning to war — in part to the plague’s debasing impact on morals, ethics, and religion.

November 19, 2014

A worthwhile Zambian initiative

Tim Worstall unexpectedly finds himself on the same side of an economic and political question as a Green Party politician from Zambia:

This strikes me as being one of the very few good ideas that has been put forward at any recent election in any country that I’m aware of. A Zambian politician has decided that, given that the world seems to be moving toward legal medical marijuana at least, if not full legalisation, then that country should make use of its comparative and absolute advantage in growing the stuff and thus supply it to the rest of the world. […]

It’s slightly disconcerting to find myself agreeing with a politician, let alone one from the Green Party, but as I say this strikes me as an excellent policy.

Let’s start from the beginning: all of us liberals (whether economic or social liberals) agree that allowing people to legally toke is a thoroughly good idea. The drug itself is almost entirely harmless (obviously less so than tobacco for example, and those stories about it bringing on schizophrenia and the like are more to do with people becoming schizophrenic self-medicating than anything else) and being banged up in a jail cell, convicted of a felony, for having possession of a joint or two is going to do far more harm to your life chances than actually smoking them.

If we’re going to agree to that (and I agree people not liberals of any flavour may not) then similarly clearly we would like the best dope we can get at the lowest possible price. Given that this is true of every other product we consume it’s going to be true of this one too. And that means that if other places around the world can produce it better, or more cheaply, or some combination of the two, than we can then we should be trading with them.

October 14, 2014

Reason.tv – 3 Reasons the US MILITARY Should NOT Fight Ebola

Published on 14 Oct 2014

President Obama is sending thousands of U.S. troops to West Africa to fight the deadly Ebola virus. Their mission will be to construct treatment centers and provide medical training to health-care workers in the local communities.

But is it really a good idea to send soldiers to provide this sort of aid?

Here are 3 reasons why militarizing humanitarian aid is a very bad idea

October 13, 2014

The Royal Navy’s “weirdest” ship

David Axe on what he describes as the weirdest ship in the Royal Navy:

Royal Fleet Auxiliary vessel RFA Argus pictured supporting Operation Herrick in Afghanistan (via Wikipedia)

The British Royal Navy is deploying the auxiliary ship RFA Argus to Sierra Leone in West Africa in order to help health officials contain the deadly Ebola virus.

If you’ve never heard of Argus, you’re not alone. She’s an odd, obscure vessel — an ungainly combination of helicopter carrier, hospital ship and training platform.

But you’ve probably seen Argus, even if you didn’t realize it. The 33-year-old vessel played a major role in the 2013 zombie movie World War Z, as the floating headquarters of the U.N.

[…]

The 575-foot-long Argus launched in 1981 as a civilian container ship. In 1982, the Royal Navy chartered the vessel to support the Falklands War … and subsequently bought her to function as an aviation training ship, launching and landing helicopters.

Argus’ long flight deck features an odd, interrupted layout, with a structure — including the exhaust stack — rising out of the deck near the stern.

Weirdly, the deck’s imperfect arrangement is actually an asset in the training role. Student aviators on Argus must get comfortable landing in close proximity to obstacles, which helps prepare them for flying from the comparatively tiny decks of frigates and other smaller ships.

August 14, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part ten of a series)

We’re edging ever close to the start of the Great War (no, I don’t know exactly how many more parts this will take … but we’re more than halfway there, I think). You can catch up on the earlier posts in this series here (now with hopefully helpful descriptions):

- Why it’s so difficult to answer the question “Who is to blame?”

- Looking back to 1814

- Bismarck, his life and works

- France isolated, Britain’s global responsibilities

- Austria, Austria-Hungary, and the Balkan quagmire

- The Anglo-German naval race, Jackie Fisher, and HMS Dreadnought

- War with Japan, revolution at home: Russia’s self-inflicted miseries

- The First Balkan War

- The Second Balkan War

The Balkans were the setting for two major wars among the regional powers (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Rumania, and the Ottoman Empire), but the wars had not spread to the rest of the continent. This run of good luck was not going to last much longer. We turn our attention to Britain, France, and Russia … as unlikely a set of allies as you’d find in the 1880s, now in the process of discovering a common threat in Europe.

Sir Edward Grey and Britain’s progress from “splendid isolation” to official ambivalence

The British government had spent most of the previous century staying out of continental disputes, only rarely becoming politically or militarily involved. Late in the nineteenth century, this began to change, and Britain started paying closer attention to what was happening on the continent and moving slowly toward re-engagement. While the British and the French had spent more time as enemies or as mutually distrustful neutrals, France was now looking across the Channel for much more than mere neutrality.

Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary 1905-1916

Sir Edward Grey had become foreign secretary on the formation of the Liberal government in December 1905, and remained in post until the end of 1916, so becoming the longest-serving holder of the post. Sir Edward brought diplomatic gravitas to his work in 1914. He had already convened the meeting of ambassadors that had contained and concluded the two Balkan wars of 1912-13. When the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on June 28 prompted a third Balkan crisis, it seemed unlikely to have any direct effect on British interests, but Sir Edward might still prove central to its resolution. If the “concert of Europe”, the international order created in 1814-15 after the Napoleonic wars, still had life, the foreign secretary was the person best placed to animate it.

Sir Edward’s qualifications for such responsibility were of recent coinage. Notoriously idle as a young man, he had been sent down from Oxford, but returned to get a third in jurisprudence. He entered politics as much through Whig inheritance as ambition. He spoke no foreign language and, when foreign secretary, never travelled abroad – or at least not until he had to accompany King George V to Paris in April 1914. He seemed happier as a country gentleman, enjoying his enthusiasms of fishing and ornithology. His first wife increasingly refused to come to London, remaining at Fallodon, the family seat in Northumberland. Their life together was chaste and childless, but not unaffectionate.

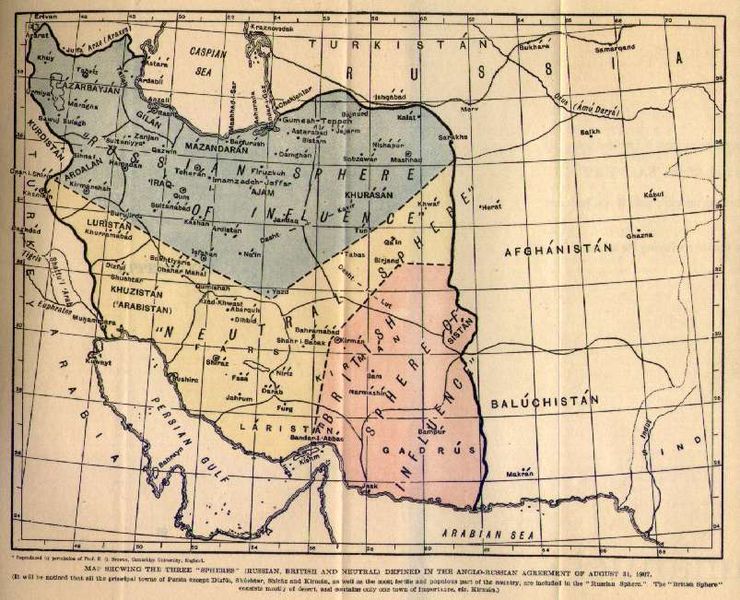

Soon after becoming Foreign Secretary, Grey was careful to assure Russian ambassador Count Alexander Benckendorff that he wanted a closer and less fraught relationship with St. Petersburg. Britain’s long-running dispute with the expanding Russian Empire in Asia stood in the way of any co-operation between the two great powers: the “Great Game” across central Asia had been in progress for nearly a century and neither side trusted the other. British concerns that any advance of Russian interests across that vast swathe of land were part of long term plans to destabilize the Indian frontier and eventually to absorb India. Whether these fears were realistic is beside the point: they had driven Raj policy in India despite the low chance of them turning into actual dangers. The disagreements were partially settled with the Anglo-Russian Convention in 1907, where both Russian and British regional interests were codified:

Formally signed by Count Alexander Izvolsky, Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire, and Sir Arthur Nicolson, the British Ambassador to Russia, the British-Russian Convention of 1907 stipulated the following:

- That Persia would be split into three zones: A Russian zone in the north, a British zone in the southeast, and a neutral “buffer” zone in the remaining land.

- That Britain may not seek concessions “beyond a line starting from Qasr-e Shirin, passing through Isfahan, Yezd (Yazd), Kakhk, and ending at a point on the Persian frontier at the intersection of the Russian and Afghan frontiers.”

- That Russia must follow the reverse of guideline number two.

- That Afghanistan was a British protectorate and for Russia to cease any communication with the Emir.

A separate treaty was drawn up to resolve disputes regarding Tibet. However, these terms eventually proved problematic, as they “drew attention to a whole range of minor issues that remained unsolved”.

While the convention did not resolve every outstanding issue between the two imperial powers, it smoothed the path to further negotiations on European issues. One of the things the two had to consider was the expansion of German activity in Ottoman territory, especially the Baghdad Railway project, which threatened to extend German influence deep into the oil producing regions of Mesopotamia just as Britain was contemplating switching the Royal Navy from coal to oil. German engineers and financiers had already proven their worth to the Ottomans by building the Anatolian Railway in the 1890s, connecting Constantinople with Ankara and Konya.

Vernon Bogdanor’s recent History Today article explains Grey’s role in bringing Britain into the war alongside the French and Russians:

The growth of German power posed a challenge to an international system based on the Concert of Europe, developed at the Congress of Vienna following the defeat of Napoleon, whereby members could call a conference to resolve diplomatic issues, a system Britain, and particularly the Liberals in government in 1914, were committed to defend. Sir Edward Grey had been foreign secretary since 1905, a position he retained until 1916, the longest continuous tenure in modern times. He was a right-leaning Liberal who found himself subject to more criticism from his own backbenchers than from Conservative opponents. In his handling of foreign policy his critics alleged that Grey had abandoned the idea of the Concert of Europe and was worshipping what John Bright had called ‘the foul idol’ of the balance of power. They suggested that he was making Britain part of an alliance system, the Triple Entente, with France and Russia and that he was concealing his policies from Parliament, the public and even from Cabinet colleagues. By helping to divide Europe into two armed camps he was increasing the likelihood of war.

On his appointment in December 1905 Grey had indeed maintained the loose Anglo-French entente of 1904, which the Conservatives of the previous government had negotiated. He extended that policy by negotiating an entente with France’s ally, Russia, in 1907. In 1905 France was embroiled in a conflict with Germany over rival claims in Morocco. The French had essentially said to Lord Lansdowne, Grey’s Conservative predecessor: ‘Suppose this conflict leads to war – if you are to support us, let us consult together on naval matters to consider how your support can be made effective.’ The Conservatives had responded that, while they would discuss contingency plans, they could not make any commitments.

Grey continued the naval conversations and extended them to include military dialogue. He informed the prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman, and two senior ministers of these talks, but not the rest of the Cabinet. Nevertheless, Britain could not be committed to military action without the approval of both Cabinet and Parliament. In November 1912, at the insistence of the Cabinet, there was an exchange of letters between Grey and the French ambassador, Paul Cambon, making it explicit that Britain was under no commitment, except to consult, were France to be threatened. In 1914, furthermore, the French never suggested that Britain was under any sort of obligation to support them, only that it would be the honourable course of action.

Romancing the bear, romancing the lion: France breaks out of imposed isolation

As I discussed back in part four of this series, the French had been left diplomatically isolated in Europe by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, but that began to change as Kaiser Wilhelm II took the throne and started imposing his will on German foreign policy. French money opened opportunities for French diplomacy, to the long-term benefit of French security. The Franco-Russian alliance was signed in 1894, signifying the end of French encirclement (Bismarck’s policy) and the start of German encirclement (Kaiser Wilhelm’s nightmare).

Britannia and Marianne dancing together on a 1904 French postcard: a celebration of the signing of the Entente Cordiale. (via Wikipedia)

French public opinion was still ambivalent at best about Britain — the PR and humanitarian disaster that was the Boer War had only just faded from the headlines, and there was still much resentment over the Fashoda incident — but the French government recognized the importance of gaining British support (and the British government was conscious of how low their international reputation had gone). Huw Strachan:

The previous Conservative government had in 1895 moved from “splendid isolation” to embrace the need to form alliances. But it was Sir Edward who narrowed these options by excluding the possibility of a deal with Germany. As a Liberal Imperialist, concerned by the evidence of British decline in the South African war, Sir Edward increasingly fixed Britain to France and then to Russia. The latter relationship may have looked frayed by 1914, but that with France was buttressed by military and naval talks. The result was not so much a balance of power in Europe as the isolation of Germany.

Moroccan crises and using the Kaiser as a bargaining chip

The First Moroccan Crisis of 1905-6 was a potential flashpoint between the Entente Cordiale and the German Empire. Germany was hoping to split the Entente or at least to gain territorial concessions in exchange for a resolution. Kaiser Wilhelm was on a cruise to the Mediterranean and had been intending to bypass Tangier, but the situation was manipulated by the Foreign Office in Berlin so that he eventually felt he had to put in an appearance. In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan describes the scene:

Although Bülow had repeatedly advised him to stick to polite formalities, Wilhelm got carried away in the excitement of the moment. To Kaid Maclean, the former British soldier who was the sultan’s trusted advisor, he said, “I do not acknowledge any agreement that has been come to. I come here as one Sovereign [sic] paying a visit to another perfectly independent sovereign. You can tell [the] Sultan this.” Bülow had also advised his master not to say anything at all to the French representative in Tangier, but Wilhelm was unable to resist reiterating to the Frenchman that Morocco was an independent country and that, furthermore, he expected France to recognize Germany’s legitimate interests there. “When the Minister tried to argue with me,” the Kaiser told Bülow, “I said ‘Good Morning’ and left him standing.” Wilhelm did not stay for the lavish banquet which the Moroccans had prepared for him but before he set off on his return ride to the shore, he found time to advise the sultan’s uncle that Morocco should make sure that its reforms were in accordance with the Koran. (The Kaiser, ever since his trip to the Middle East in 1898, had seen himself as the protector of all Muslims.) The Hamburg sailed on to Gibraltar, where one of its escort ships accidentally managed to ram a British cruiser.

Tension rose so high that both Germany and France were looking to their mobilization timetables (France cancelled all military leave and Germany started moving reserve units to the frontier) before the diplomats were able to agree to meet at the conference table rather than the battlefield. The Algeciras Conference lasted from January to April, 1906, and the French generally had the better of the negotiations (with support from Britain, Russia, Italy, Spain, and the United States) while the Germans found themselves supported only by the Austro-Hungarian delegation. France ended up making a few token concessions, but overall retained their position in Morocco.

The Agadir Crisis of 1911 was the second incident in Morocco, where Germany tried a little bit of literal gunboat diplomacy with the gunboat SMS Panther. The port of Agadir was closed to foreign trade, but the Panther (and later the light cruiser SMS Berlin) was sent to “protect German nationals” in southern Morocco from rebel forces. A minor problem turned out to be that there were no conveniently threatened Germans in the region. Margaret MacMillan:

The Foreign Ministry only got round to getting support for its claim that German interests and German subjects were in danger in the south of Morocco a couple of weeks before the Panther arrived off Agadir, when it asked a dozen German firms to sign a petition (which most of them did not bother to read) requesting German intervention. When the German Chancellor, Bethmann, produced this story in the Reichstag he was met with laughter. Nor were there any German nationals in Agadir itself. The local representative of the Warburg interests who was some seventy miles to the north started southwards on the evening of July 1. After a hard journey by horse along a rocky track, he arrived at Agadir on July 4 and waved his arms to no effect from the beach to attract the attention of the Panther and the Berlin. The sole representative of the Germans under threat in southern Morocco was finally spotted and picked up the next day.

France reacted to the German provocation, despite efforts by Sir Edward Grey to restrain them: eventually he recognized that “what the French contemplate doing is not wise, but we cannot under our agreement interfere”. German public opinion, on the other hand, was ecstatic:

After its setbacks earlier on in Morocco and in the race for colonies in general, with the fears of encirclement in Europe by the Entente powers, Germany was showing that it mattered. “The German dreamer awakes after sleeping for twenty years like the sleeping beauty,” said one newspaper.

[…]

In Germany, public opinion, which had been largely indifferent to colonies ten years earlier, now was seized with their importance. The German government, which was already under considerable pressure from those German businesses with interests in Morocco, felt that it had much to gain by taking a firm stand. […] The temptation for Germany’s new Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Holweg, and his colleagues to have a good international crisis to bring all Germans together in support of their government was considerable.

Eventually, after negotiations, France and Germany signed the Treaty of Fez, which granted France Germany’s recognition of her rights in Morocco in exchange for ceded French territory in French Equatorial Africa (which was annexed to the existing German colony in Togoland), including direct access to the Congo River. In addition, Spain was granted rights to a portion of northern Morocco which became Spanish Morocco.

Not part of the treaty terms, but of rather greater significance in the near future, France and Britain agreed to share responsibility for the naval defence of France: the Royal Navy took on the responsibility for defending the north coast of France, while the French navy redeployed almost all ships to the western Mediterranean with the explicit agreement to defend British interests in the region.

I’m finding each successive part of this blog series to be taking longer to put together, and not from a lack of material! I’m hoping to have the next installment posted sometime this weekend or early next week.

August 13, 2014

Pessimism from the Rational Optimist

Matt Ridley is somewhat uncharacteristically concerned about the major Ebola outbreak in west Africa:

As you may know by now, I am a serial debunker of alarm and it usually serves me in good stead. On the threat posed by diseases, I’ve been resolutely sceptical of exaggerated scares about bird flu and I once won a bet that mad cow disease would never claim more than 100 human lives a year when some “experts” were forecasting tens of thousands (it peaked at 28 in 2000). I’ve drawn attention to the steadily falling mortality from malaria and Aids.

Well, this time, about ebola, I am worried. Not for Britain, Europe or America or any other developed country and not for the human race as a whole. This is not about us in rich countries, and there remains little doubt that this country can achieve the necessary isolation and hygiene to control any cases that get here by air before they infect more than a handful of other people — at the very worst. No, it is the situation in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea that is scary. There it could get much worse before it gets better.

This is the first time ebola has got going in cities. It is the first time it is happening in areas with “fluid population movements over porous borders” in the words of Margaret Chan, the World Health Organisation’s director-general, speaking last Friday. It is the first time it has spread by air travel. It is the first time it has reached the sort of critical mass that makes tracing its victims’ contacts difficult.

One of ebola’s most dangerous features is that kills so many health workers. Because it requires direct contact with the bodily fluids of patients, and because patients are violently ill, nurses and doctors are especially at risk. The current epidemic has already claimed the lives of 60 healthcare workers, including those of two prominent doctors, Samuel Brisbane in Liberia and Sheik Umar Khan in Sierra Leone. The courage of medics in these circumstances, working in stifling protective gear, is humbling.