In The Critic, Darren O’Byrne reviews some recent books on German society between the Armistice of 1918 and the rise of Hitler, including Frank McDonough’s The Weimar Years: Rise and Fall 1918–1933.

One of the latest additions to the canon is Frank McDonough’s The Weimar Years (1918–33). A prequel to his two-volume narrative history of the Third Reich, The Hitler Years, it sets out to explain the Nazis’ rise to power by examining the reasons why democracy failed in Germany. Like the earliest histories of the period, the Republic is not examined on its own terms but rather as a kind of backstory to what followed, the numerous crises that befell it being used to explain the ultimate catastrophe.

Structured chronologically, the book provides a devastating, play-by-play account of why, for McDonough, democracy stood little chance in Germany. Defeat in World War I, the Kaiser’s abdication and the humiliating terms of the Versailles treaties challenged the legitimacy of the Republic from the start, as did its failure to contain political violence. Crippling inflation and mounting government debt, exacerbated by the obligation to pay reparations to the Allies, hampered German economic recovery from the start and threatened to wipe out the middle classes.

A degree of economic stability did return in the mid-1920s, but the country experienced its second “once-in-a-lifetime” economic crisis in the early 1930s, causing further instability and ultimately paving the way for Hitler. It’s a well-known story, skilfully retold for a contemporary audience by one of the foremost authorities on modern German history.

Does McDonough tell us anything we didn’t already know? The answer, in short, is no. In comparison to other recent histories of the period, more attention is paid here to high politics than Weimar’s cultural achievements, which are mentioned, but this tends to disrupt the flow of what is otherwise a high-paced, edge-of-the-seat political history of Germany’s first democracy. Despite being nearly 600 pages in length, the book’s focus is quite narrow, with little attention paid to what was happening below the national level in the federal states.

This may seem like an inane criticism. Who, after all, would demand to read more about Buckinghamshire in a political history of interwar Britain? However, the Weimar Republic, like Germany today, was a federation. Understanding what was happening in states like Prussia, which contained three-fifths of Germany’s population, is crucial to understanding the country as a whole.

Indeed, McDonough places some of the blame for Weimar’s collapse on the Social Democrats, who he argues should have participated in more national governments. Prussia was governed by an SPD-led coalition for most of the Weimar years, though, yet the Republic still fell. McDonough sees another reason for this fall in the failure to purge the military and civil service of hostile elements.

Again, Prussia replaced a considerable number of these officials with others loyal to the new democratic order, yet the Republic still fell. The book’s rigid focus on high politics, in short, obscures an understanding of the more structural reasons why democracy failed.

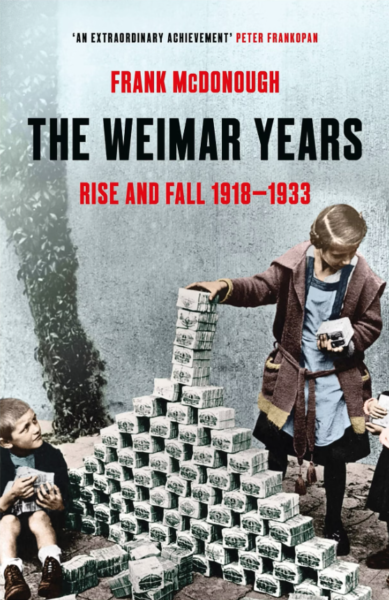

Unlike most history books, however, The Weimar Years is a genuine page-turner, full of lessons for those who want to learn something about the present from the past. It’s also a beautiful book to hold, full of period photos that help bring the story alive. This all makes the book worth reading, even if there’s not much in it that can’t be found in other histories of the period.