Following up from last week, in this week’s SHuSH newsletter Ken Whyte explains why Indigo went in the direction it chose and why it seemed like the thing to do at that time:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

Bookselling is a difficult business and it’s been especially difficult over the last twenty years. The Internet captured a lot of the used book business and shifted it online. Amazon captured a lot of the new book business and shifted it online (and bought Abebooks.com, one of the largest used book sites).

Former Indigo CEO Heather Reisman tried and failed to convince the federal government to keep Amazon south of the border back around 2002. She went so far as to sue the feds on the grounds that Amazon, as a cultural entity, was not majority-owned by Canadians and therefore operating in contravention of the Investment Canada Act. The suit went nowhere because Amazon then had no physical presence in Canada; it operated primarily through Canada Post. By the time Amazon did announce its intention to build a warehouse north of the border, early in 2010, the government had given up enforcing the Investment Canada Act. It was happy to have Amazon create new jobs.

It was when Amazon opened its Canadian warehouse that Heather began backing Indigo out of the book business. She cursed Amazon for its anticompetitive practices, not least its habit of selling books below cost to destroy competitors, and adopted the term “cultural department store” as a pivot from bookstores.

I’ve made it clear in newsletter after newsletter that I don’t like the direction Heather took Indigo but it’s only fair to look back at prevailing circumstances in 2010 and wonder if she really had a choice.

I’m sure she had stacks of research and hordes of people telling her that abandoning books was the only move. Attempting to compete with Amazon’s enormous scale and superior logistics would have struck many as a fool’s errand. Amazon would always have the largest selection, the best price, and the fastest delivery.

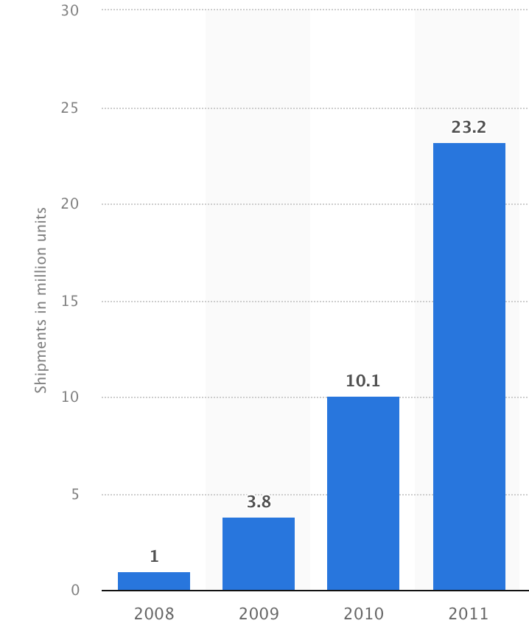

There was also a widespread belief that print was dead. E-books, e-readers, and tablets were the future, along with the “one very, very, very large single text“. Global e-reader sales were growing like this:

They were expected to keep growing. So were sales of e-books. In 2012, the Financial Post quoted data from Indigo predicting that e-books would capture 50 percent of the market in five years.

So, having played the Canadian Nationalist card and discovering that the government was willing to bluster but not to meaningfully act, Heather Reisman took the advice of her consultants and diversified away from books and into all the utter crap that currently befoul at least half of the retail space in every Indigo store. After all, the big box bookstores in the United States were clearly failing in the face of Amazon, with Borders filing for bankruptcy and Barnes & Noble staggering in the same direction. From 1999 to 2019, fully half of all the bookstores in the country disappeared.

The story isn’t as bleak as it looked in 2019, as Barnes & Noble is staging quite a comeback by concentrating on the book business. It’s a radical move, but Indigo could do far worse than cooking up a maple-flavoured version of the Barnes & Noble strategy. It might fail, but they’ll definitely fail if they keep on pretending to be a department gift store that also has a few books.