Ned Donovan recounts a very dangerous moment for the British East India Company — and the larger British economy — as a French naval squadron threatened the EIC’s China Fleet carrying a cargo that would be the rough equivalent of £750 million in today’s money:

It will not be surprising to any reader that the East India Company was arrogant. A company that, as William Dalrymple describes, had become “an empire within an empire”. It controlled much of India, had its own army, and its revenues kept Britain afloat. Its navy was also not to be sniffed at, made up of large, well-built ships (known as Indiamen) capable of being as armed as any British warship, but its commercial arrogance prevented this. Rather than fill these Indiamen with cannons and the hundreds of sailors needed to man them, it instead filled its gun ports with dummy cannons and its decks with luxurious cabins and storage for trade goods, maintaining crews only large enough to sail these ships and be stewards to its paying passengers.

Commodore Dance would have been pondering those dummy cannons as the ships he had sent to look at the four strange sail in the southwest reported back that it was four French warships, Linois’s squadron. He was practically defenceless. To protect his 30 ships and their precious cargo, he had one small armed brig named the Ganges with around a dozen guns. Up against him were the 186 guns of the French squadron, 74 in Marengo, 40 in Belle Poule, 36 in Semillante, 20 in Berceau and 16 in Aventurier. As Dance watched through his telescope, the French ships hoisted their colours, and the admiral’s flag of Linois broke out above Marengo. He needed a plan. Fast.

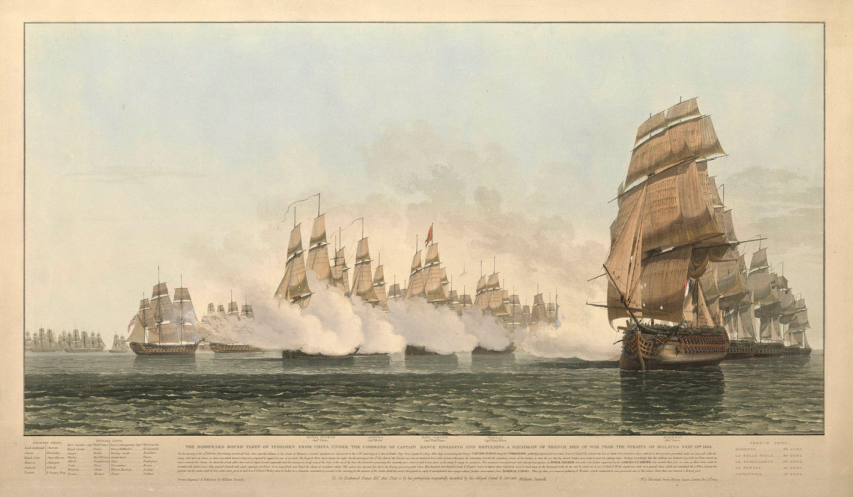

After a night of cat and mouse between the French and British, Dance ordered his convoy into a long single line and at the front put four of the largest Indiamen – the Royal George, Earl Camden, Warley, and Alfred. He then commanded that these four hoist blue ensigns, the sign of Royal Navy ships. This wasn’t the most absurd plan; the East India Company, in their arrogance, had a policy of painting their Indiamen to look like Royal Navy ships – as Dance records in his despatch: “We hoisted our colours and offered him battle.” But Linois and his ships continued to approach the convoy slowly, with Dance realising that the French intended to separate the convoy and take it apart piece by piece. It was now or never, and Dance took the initiative. At 1 pm, he ordered the Ganges, Royal George, Earl Camden, Warley and Alfred to turn and intercept the French. All the ships turned perfectly and crossed Linois, and at 1:15 pm, the French opened fire on the Royal George. In the preceding night, the convoy had put all the guns they had on these five ships and filled them with as many brave volunteers as they could. All five returned fire on the French warships, and one sailor on the Royal George was killed. I will let Dance take over here:

“But before any other ship could get into action, the enemy hauled their wind and stood away to the east under all the sail they could set. At 2 pm, I made the signal for a general chase and we pursued them until 4 pm.”

In around 40 minutes, Dance and his handful of real guns and dummy cannons had forced the French warships to withdraw under the belief it had engaged an elite squadron of Royal Navy ships. Not content with this victory, he then ordered his ships to chase the French down and stop them from returning. By the later afternoon, it was clear Linois had run, and Dance ordered his convoy to regroup and make for the safety of Malacca.

In the Straits of Malacca, Dance met the ships the Royal Navy had sent to escort him on the outbreak of war but would have been too late had the commodore not thought fast. The China Fleet passed the rest of its voyage without incident, returning to Britain in the summer of 1804.

To say the country was ecstatic would be an understatement. If the China Fleet and its £8 million had been taken, as Linois would have been perfectly able to do, it is evident that both the East India Company and Lloyds of London would have faced bankruptcy and collapse. Nathaniel Dance was knighted by George III and given a fantastic sword by Lloyds worth 100 guineas. With the sword came £5,000 (£403,000 today) from the Bombay Insurance Company and £500 a year (£40,000 today) from the East India Company, along with a share in the £50,000 given to all who sailed in convoy. Sir Nathaniel retired immediately and never took to the sea again, dying peacefully in 1827.

Poor Admiral Linois, on the other hand, never lived down the fracas, with Napoleon writing after the event, “[Linois] has shown want of courage of mind, that kind of courage which I consider the highest quality in a leader”. Despite that, Linois remained in the French navy … only to once again run into the fickleness of fate:

It is worth remarking that following the defeat at Pulo Aura, Linois had a similarly pathetic rest of the war that ended in a wonderfully ironic way. In 1806, the admiral was captured when he mistook a British squadron of warships for a merchant convoy.

Irony? That’s cosmic level stuff.