This is an excerpt from Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry, an unpublished book by the late John Sayen which is being serialized at Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook on Substack. While I haven’t read a lot on the AEF, as I’ve concentrated much more on the Canadian Corps as part of the British Expeditionary Force, I was aware that the American divisions were organized quite differently from either British or French equivalents. The significanly larger division organization — 28,000 men compared to about half that in other allied armies — was intended to give US Army units greater staying power in combat, but it didn’t work out as planned for many reasons:

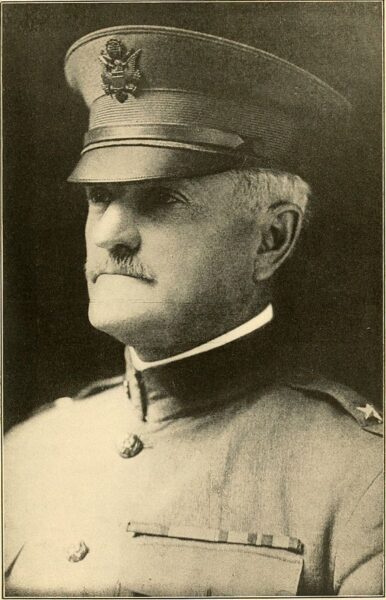

General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during the First World War.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The basic tactical concept behind the square AEF divisions under which the two regiments holding the division’s front line could be relieved by two more regiments to their rear was seriously undermined. The two regiments that were supposed to be resting were the ones that had to man all the work details. When it came time for them to relieve the front-line regiments it was, as historian Allan Millett described it, often a question “of replacing exhausted troops who had suffered casualties with exhausted troops who had not”.

It had certainly not been intended that the infantry serve as labor troops. Such tasks were supposed to have been carried out by separate regiments of pioneers modeled on those used by the French. In the French Army, pioneer regiments were lightly armed infantry serving under corps and army headquarters. They tended to consist of older men and were not the elite assault troops that filled the pioneer platoons in the infantry regiments. Though they could fight when necessary, their main function was to furnish the bulk of the semi-skilled and unskilled labor in the forward areas.

In imitation of this system the War Department raised 37 AEF pioneer regiments. These were organized as AEF infantry regiments without machinegun companies or sapper-bomber, pioneer, or one-pounder gun platoons. Only two of the 29 pioneer regiments to reach France did so before the last three months of the war. One regiment was supposed to go to each army corps and several to each army. However, the AEF pioneers proved to be so badly trained and led (even by AEF standards) that after front line service involving a mere 241 battle casualties most of the pioneers were pulled out of combat to serve as unarmed laborers far to the rear.

It wasn’t just combat casualties that reduced US divisional effectiveness:

Early planning had called for one third of all divisions to serve as replacement depots or field-training units charged with keeping the remaining combat divisions filled with men. The system broke down, however, as heavy losses forced the intended depot divisions to be used as combat units instead. Only six of the 42 AEF divisions to reach France before the Armistice (three more arrived soon afterwards) actually served as replacement or training depots instead of the 14 that were needed.

As an emergency measure, five combat divisions, and later two of the depot divisions, were skeletonized to immediately create urgently needed replacements but, of course, this rendered them useless for either combat or depot duty. Another division had to be fragmented to provide men for rear area support duties and yet another was broken up to flesh out three French divisions. Even in February 1918, (before the AEF had seen serious combat) the four combat divisions in the AEF I Corps were 8,500 men short (mostly in their infantry regiments). The 41st Division, which was the corps’ depot division and charged with supplying those missing men was itself 4,500 men short. By early October 1918, AEF combat units needed 80,000 replacements but only 45,000 were expected before 1 November. At the end of October, the total shortfall had reached 119,690, including 95,303 infantrymen and 8,210 machine gunners. Only 66,490 replacement infantrymen and machine gunners would be available any time soon. For most of the war, AEF combat divisions were typically short by 4,000 men. After August 1918, even divisions fresh from the United States usually needed men. Too many divisions had been organized too quickly.

Of course, the root cause of the manpower problem was even more basic. Men were being used up faster than they could be replaced. The AEF suffered most of its battle casualties between 25 April and 11 November 1918, a period of less than seven months. These combat losses amounted to between 260,000 and 290,000 officers and men, of whom some 53,000 were killed in action or died of their wounds. The rest were wounded or gassed but 85% of these subsequently returned to duty. About 4,500 AEF prisoners of war were repatriated after the Armistice. Five thousand others became victims of “shell shock.” Accidental casualties, including those known to have been caused by “friendly fire” (total friendly fire losses must have been considerable, given the poor state of infantry-artillery coordination), or disease or self-inflicted wounds, far exceeded those sustained in battle.

Two thirds of the more than 125,000 Army and Marine Corps deaths between April 1917 and May 1919 occurred overseas and nearly half (57,000) were from disease. Pneumonia and influenza-pneumonia, which produced the infamous “swine flu” epidemic of 1918, were the chief killers but many victims who became ill before the Armistice did not actually die until after it. Between 14 September and 8 November 1918 some 370,000 cases were reported in the United States alone. Within less than two years between one quarter and one third of the men serving in the US Army had died or became temporarily or permanently disabled by battle, disease, accident, or misconduct. Had such losses continued, the United States might soon have begun to experience the same war weariness and manpower “burnout” that had been plaguing the British, French, and Germans.

With regard to the infantry, the woes of the AEF replacement and training system were much increased by the prevailing belief that because an infantryman needed few technical skills he had little to learn and could be quickly and easily trained from very average human material. Technical arms such as the engineers, signal corps, artillery, and, more significantly, the air corps got the pick of the AEF’s manpower.

The infantry soon became the repository for those deemed unfit for anything better. Many infantrymen saw themselves, and were seen, as cannon fodder. Morale and cohesion were further undermined by the practice of stripping new divisions of men (often before they had even left the United States) to fill older ones. The better men and officers avoided infantry duty to seek less demanding “technical” jobs. Of course, training suffered grievously.

As demands for replacements became more insistent, men who supposedly had received several months’ training were appearing in the front lines not knowing how to load their rifles. Others proved to be recent immigrants who could not speak English. Infantrymen of small physique who might have rendered useful service in non-infantry roles, soon collapsed under the physical burdens placed on them and became liabilities rather than assets. Losses among even good infantry were heavy enough but mediocre infantry melted away at an astonishing rate. Indiscipline, disorganization, and ignorance inevitably increased losses by what must have seemed like a couple of orders of magnitude. These losses were likely to be replaced, if at all, by men of even lower caliber.

Straggling was an especially pernicious problem, which the military police had only limited success in controlling. Even more than actual casualties, it caused some units to simply evaporate. During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, for example, one division reported that it was down to only 1,600 effective men. However, soon after it arrived at a rest area, it reported 8,400 men in its infantry regiments alone.