Once again, Ted Gioia’s Honest Broker Substack has something interesting I’d like to share with you (I wouldn’t blame you at all for cutting out the middleman and just subscribing for yourself):

Today I want to focus on a single paragraph published in 1960.

You’re asking yourself: How much can a single paragraph matter — especially if it was written 63 years ago? But read it first and judge for yourself.

It’s a chilling paragraph.

[…]

By any measure, [Paul Goodman] was one of the most eccentric thinkers of the era. Yet he anticipated our current situation with more insight than any of his peers.

Let’s look at this one paragraph from the Preface to Growing Up Absurd. It’s a long paragraph — it takes up most of two pages. So we will break it down into pieces.

Goodman begins with a puzzle he needs to solve — society is stagnating everywhere, and we all can see it. But there’s no action plan to fix it. There’s a lot of huffing and puffing and finger-pointing everywhere, but nobody has even started on developing a practical agenda.

According to Goodman, this is because people “have ceased to be able to imagine alternatives”. Everybody accepts that the current system “is the only possibility of society, for nothing else is thinkable”.

Now comes his analysis, and — to my surprise — Goodman begins by talking about music. This was the last thing I expected in a social critique, but for Goodman the manufacturing of hit songs is a metaphor for everything else that’s wrong in a stagnant society.

He writes:

Let me give a couple of examples of how this [inability to imagine healthy alternatives] works. Suppose (as is the case) that a group of radio and TV broadcasters, competing in the Pickwickian fashion of semi-monopolies, control all the stations and channels in an area, amassing the capital and variously bribing Communications Commissioners in order to get them; and the broadcasters tailor their programs to meet the requirements of their advertisers of the censorship, of their own slick and clique tastes, and of a broad common denominator of the audience, none of whom may be offended: they will then claim not only that the public wants the drivel that they give them, but indeed that nothing else is being created. Of course it is not! Not for these media; why should a serious artist bother?

When I first read this, I was dumbstruck. Goodman wrote this during the winter of 1959 and 1960, when radio stations were independent and freewheeling. Back in my teen years, a single business was only allowed to control one AM station and one FM station. In 1985 this was increased to 12 stations on each band. And in 1994 this was raised again, this time to 20 AM stations and 20 FM stations.

But then all hell broke lose when the Telecommunications Act of 1996 passed in the Senate by a 91 to 5 margin and was signed into law. Now the sky was the limit — and all the airwaves it contained.

Soon Clear Channel Communications owned more than 1,200 radio stations in some 300 cities. The company began the process of standardizing and homogenizing our musical culture. We still suffer from that today.

Even after radio started losing influence in the Internet Age, huge streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music, etc.) ensured that access to the ears of America would be controlled by a tiny number of huge corporations. A musical culture that was once local, indie, and flexible has become centralized, corporatized, and stagnant.

How could Paul Goodman even dream of such a scenario back in 1960? That future was decades away at the time.

But we are only at the start of this visionary paragraph. Goodman now explains that the same thing will happen in universities.

Colleges and schools were small and non-bureaucratic back in 1960. Yet Goodman sees a crisis looming. On the next page Goodman warns against “the topsy-turvy situation that a teacher must devote himself to satisfying the administrator and financier rather than to doing his job, and a universally admired teacher is fired for disobeying an administrative order that would hinder teaching”.

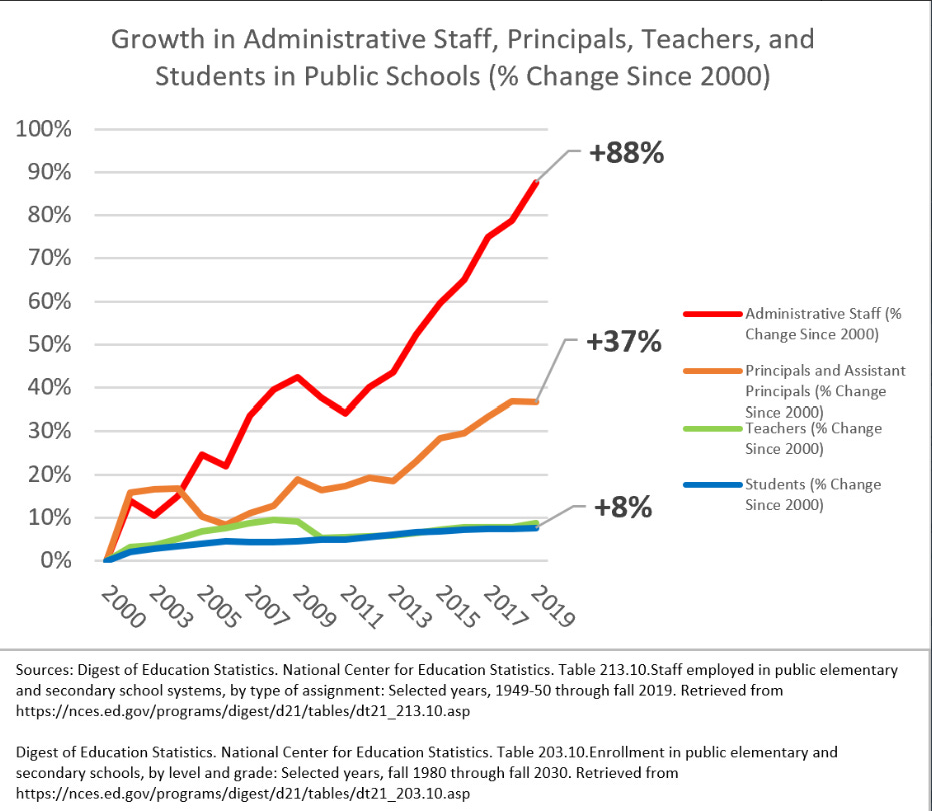

Administration at US colleges has grown exponentially in the last two decades and has turned almost every academic institution into a plodding bureaucracy — but how in the world did Goodman anticipate this in 1960?

Now let’s return to our chilling paragraph. Immediately after discussing radio stations, Goodman adds a gargantuan sentence. It jumps all over the place but hits the target at every twist and turn:

Or suppose again (as is not quite the case) that in a group of universities only faculties are chosen that are “safe” to the businessmen trustees or the politically appointed regents, and these faculties give out all the degrees and licenses and union cards to the new generation of students, and only such universities can get Foundation or government money for research, and research is incestuously staffed by the same sponsors and according to the same policy, and they allow no one but those they choose, to have access to either the classroom or expensive apparatus: it will then be claimed that there is no other learning or professional competence; that an inspired teacher is not “solid”; that the official projects are the direction of science; that progressive education is a failure; and finally, indeed — as in Dr. James Conant’s report on the high schools — that only 15 per cent of the youth are “academically talented” enough to be taught hard subjects.

Here in a nutshell is the credentialing crisis of our times. Learning is replaced by exclusionary certification programs that limit career opportunities — unless you take out loans and “purchase” the necessary credential from these academic gatekeepers.

This has become so destructive in our own time that many are crushed by student loans, and others seek ingenious ways of bypassing college entirely. There’s no way that Goodman could have grasped this in 1960 — when only 7.7 percent of Americans had college degrees.

Nor could he have known about the replicability crisis in science or the destructive games now played in awarding of scientific grants. Those are the problems of our times — not his.

But somehow Paul Goodman saw it coming.