In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers why the telegraph took so long to be invented and describes some of the precursors that filled that niche over the centuries:

… I’ve also long wondered the same about telegraphs — not the electric ones, but all the other long-distance signalling systems that used mechanical arms, waved flags, and flashed lights, which suddenly only began to really take off in the eighteenth century, and especially in the 1790s.

What makes the non-electric telegraph all the more interesting is that in its most basic forms it actually was used all over the world since ancient times. Yet the more sophisticated versions kept on being invented and then forgotten. It’s an interesting case because it shows just how many of the budding systems of the 1790s really were long behind their time — many had actually already been invented before.

The oldest and most widely-used telegraph system for transmitting over very long distances was akin to Gondor’s lighting of the beacons, capable only of communicating a single, pre-agreed message (with flames often more visible at night, and smoke during the day). Such chains of beacons were known to the Mari kingdom of modern-day Syria in the eighteenth century BC, and to the Neo-Assyrian emperor Ashurbanipal in the seventh century BC. They feature in the Old Testament and the works of Herodotus, Aeschylus, and Thucydides, with archaeological finds hinting at even more. They remained popular well beyond the middle ages, for example being used in England in 1588 to warn of the arrival of the Spanish Armada. And they were seemingly invented independently all over the world. Throughout the sixteenth century, Spanish conquistadors again and again reported simple smoke signals being used by the peoples they invaded throughout the Americas.

But what we’re really interested in here are systems that could transmit more complex messages, some of which may have already been in use by as early as the fifth century BC. During the Peloponnesian War, a garrison at Plataea apparently managed to confuse the torch signals of the attacking Thebans by waving torches of their own — strongly suggesting that the Thebans were doing more than just sending single pre-agreed messages.

About a century later, Aeneas Tacticus also wrote of how ordinary fire signals could be augmented by using identical water clocks — essentially just pots with taps at the bottom — which would lose their water at the same rate and would have different messages assigned to different water levels. By waving torches to signal when to start and stop the water clocks (Ready? Yes. Now start … stop!), the communicator could choose from a variety of messages rather than being limited to one. A very similar system was reportedly used by the Carthaginians during their conquests of Sicily, to send messages all the way back to North Africa requesting different kinds of supplies and reinforcement, choosing from a range of predetermined signals like “transports”, “warships”, “money”.

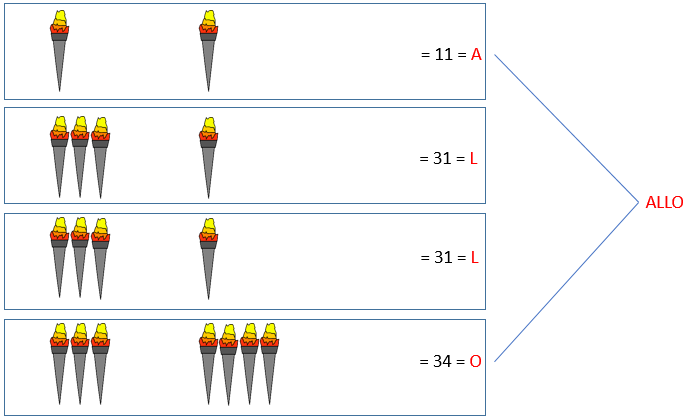

Diagram of a fire signal using the Polybius cipher.

Created by Jonathan Martineau via Wikimedia Commons.By the second century BC, a new method had appeared. We only know about it via Polybius, who claimed to have improved on an even older method that he attributed to a Cleoxenus and a Democleitus. The system that Polybius described allowed for the spelling out of more specific, detailed messages. It used ten torches, with five on the left and five on the right. The number of torches raised on the left indicated which row to consult on a pre-agreed tablet of letters, while the number of torches raised on the right indicated the column. The method used a lot of torches, which would have to be quite spread out to remain distinct over very long distances. So it must have been quite labour-intensive. But, crucially, it allowed for messages to be spelled out letter by letter, and quickly.

Three centuries later, the Romans were seemingly still using a much faster and simpler version of Polybius’s system, almost verging on a Morse-like code. The signalling area now had a left, right, and middle. But instead of signalling a letter by showing a certain number of torches in each field all at once, the senders waved the torches a certain number of times — up to eight times in each field, thereby dividing the alphabet into three chunks. One wave on the left thus signalled an A, twice on the left a B, once in the middle an I, twice in the middle a K, and so on.

By the height of the Roman Empire, fire signals had thus been adapted to rapidly transmit complex messages over long distances. But in the centuries that followed, these more sophisticated techniques seem to have disappeared. The technology appears to have regressed.