Real Time History

Published 7 Apr 2022Sign up at https://curiositystream.com/realtimeh… and get Nebula bundled in.

Smolensk is an important symbolic city to the Russians in 1812, for Napoleon it’s a strategic objective he wants to conquer to improve is deteriorating supply situation. The Battle of Smolensk leads to an inferno in the city, it gets virtually destroyed and nearly all residents flee.

» SUPPORT US ON PATREON

https://patreon.com/realtimehistory» THANK YOU TO OUR CO-PRODUCERS

John Ozment, James Darcangelo, Jacob Carter Landt, Thomas Brendan, Kurt Gillies, Scott Deederly, John Belland, Adam Smith, Taylor Allen, Rustem Sharipov, Christoph Wolf, Simen Røste, Marcus Bondura, Ramon Rijkhoek, Theodore Patrick Shannon, Philip Schoffman, Avi Woolf,» SOURCES

Der Feldzug der Österreicher gegen Rußland im Jahre 1812. Aus offiziellen Quellen von Ludwig Freiherrn von Welden, Wien 1870.

Vojtêch Kessler: Der österreichische Pyrrhos – Der Feldzug des österreichischen Auxiliar-Korps im Jahre 1812 in den Briefen des Oberbefehlshabers Karl Fürst von Schwarzenberg an seine Frau.

Boudon, Jacques-Olivier. Napoléon et la campagne de Russie en 1812. 2021.

Holzhausen, Paul. Die Deutschen in Russland 1812. Leben und Leiden auf der Moskauer Heerfahrt. Berlin 1912.

Lieven, Dominic. Russia Against Napoleon. 2010.

Rey, Marie-Pierre. L’effroyable tragédie: une nouvelle histoire de la campagne de Russie. 2012.

Zamoyski, Adam. 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March on Moscow. 2005.» OUR STORE

Website: https://realtimehistory.net»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Above Zero

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Toni Steller

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Digital Maps: Canadian Research and Mapping Association (CRMA)

Research by: Jesse Alexander

Fact checking: Florian WittigChannel Design: Simon Buckmaster

Contains licensed material by getty images

Maps: MapTiler/OpenStreetMap Contributors & GEOlayers3

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2022

April 8, 2022

Napoleon Conquers A Heap of Ashes – Battle of Smolensk 1812

The structure of the Chinese government

Scott Alexander reviews The Third Revolution, by Elizabeth Economy, although as he says up front, “It’s a look through recent Chinese history, with The Third Revolution as a very loose inspiration.”:

How Does China’s Government Work?

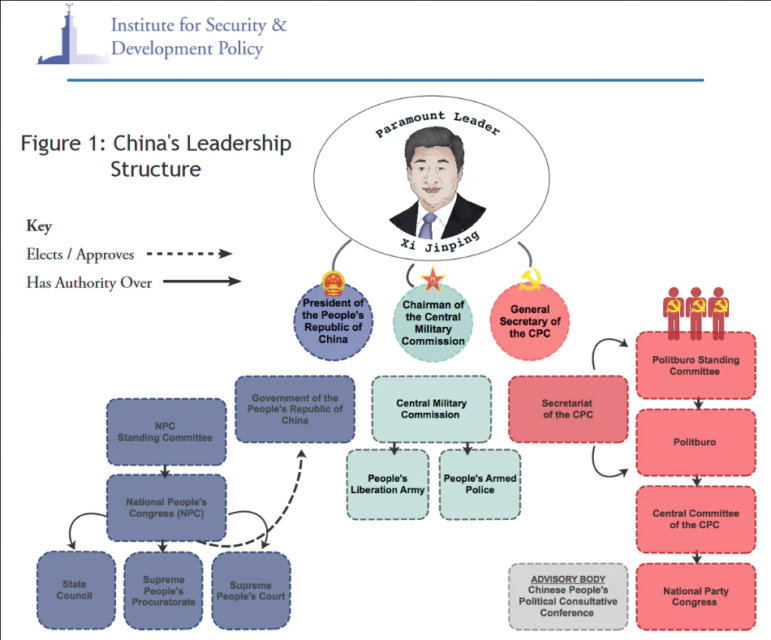

The traditional answer is a flowchart like this one (source):

But you could give a similarly convoluted flowchart for America, and it would tell people much less than words like “democracy” or “balance of powers”. What’s the Chinese equivalent?

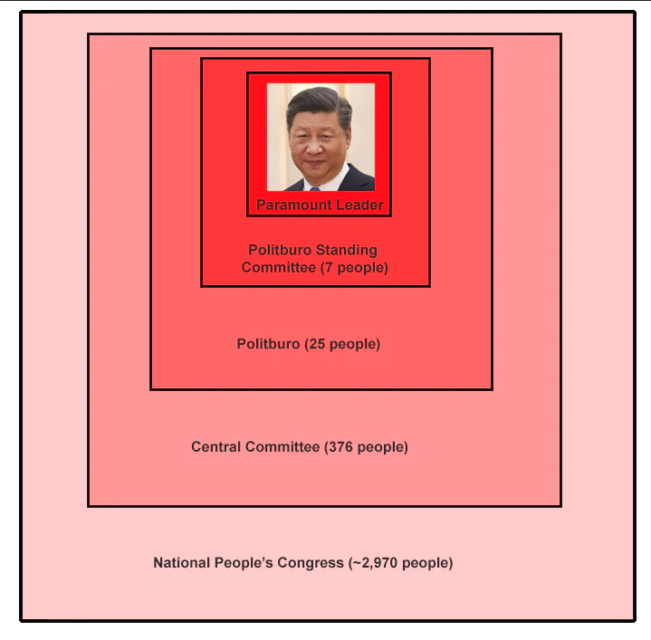

I found it a little more helpful to see it diagrammed it as a series of nested squares:

The inner levels have real power, and the outer layers are theoretically overseers but actually rubber stamps. Things get more and more rubber-stampy as you go out, culminating in the National People’s Congress, which recently voted to re-elect Xi by a vote of 2,970 in favor, 0 against — it’s so irrelevant that it’s literally called “the NPC”.

Who chooses the members of the inner groups? In theory, the outer groups; for example, the Central Committee is supposed to elect the Politburo Standing Committee. In practice, these selections tend to be of the “2,970 in favor, 0 against” variety, so they must be taking marching orders from someone. Who? The Chinese government doesn’t talk about it much, but probably the members of the Politburo Standing Committee hand-pick everyone, including the Paramount Leader and their own successors.

How do they pick? Mostly patron-client relationships. Every leading politician cultivates a network of loyal supporters; if he takes power, he tries to put as many of his people into top posts as he can. The seven Politburo members wheel and deal with each other about whose clients should get which positions, including any unoccupied Politburo seats.

If the two word description of US politics is “democracy, checks-and-balances”, then the two word description of Chinese politics is “oligarchy, patrons-and-clients”. If this seems exotic, it shouldn’t: it’s not much different from how the US fills unelected posts like “ambassador” and “White House staffer”. The Trump presidency put this into especially sharp relief, either because Trump did it more blatantly than usual or just because Trump’s clients were so obviously different from the normal Washington crowd. Consider eg the appointment of Jeff Sessions (among the first Congressmen to endorse Trump) as Attorney General.

In the US, this is a peripheral part of the system, checked by democracy. In China, it’s the whole game.

Chinese C96 “Wauser” Broomhandle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 10 Nov 2016Cool Forgotten Weapons Merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

The C96 Mauser was a very popular handgun in China in the 1920s and 30s, which naturally led to a substantial number of domestically-produced copies of it. These ran the full range of quality, from dangerous to excellent. This particular example falls into the middle, appearing to be a pretty fair mechanical copy of the C96 action. However, it does exhibit classic Chinese misspelled markings — the workers who made these guns often did not actually read English (or German), and made best-guess attempts at copying the markings on authentic firearms. The result was sometimes something like the Wauser.

QotD: The fearlessness of De Gaulle

Like many monsters — for he could be a monster to those who defied him, and was often cruel and unfair to his most devoted supporters — he had enormous charm when he chose to turn it on. He was deeply mischievous and enjoyed puzzling and wrong-footing others. When he did not wish to give ground, he could be obtuse, an experience described by one victim as like “being confined … with a cormorant who spoke only cormorant.”

The evidence suggests that he was one of those dangerous people who simply do not know what fear is, and that he discovered this quite early in his long life. If a sergeant had not fallen dead on top of the young Lieutenant de Gaulle when he first went into battle at Dinant in August 1914, he would probably have died in some useless, gallant sacrifice and never have been heard of again. If he had not been knocked unconscious by the blast of a grenade at Verdun in March 1916, it is hard to believe that he would have allowed himself to be taken prisoner by the Germans. In that case he would almost certainly have died in that frightful battle, or not long afterward, another silent shade in that huge legion of shades who marched off into the dark during that appalling war.

Only his wife Yvonne was unimpressed by his grandeur, more than once urging him to retire, or puncturing his ambition. During the long, frustrating wilderness years between his wartime glory and his final presidential triumph, he mused to her that he might one day repeat his great rallying call of 1940. Using the rather patronizing endearment “Pauvre Ami,” she declared flatly, “Nobody will follow you.” He snapped back, “Shut up, Yvonne! I am old enough to know what I want to do!” In fact, on that occasion he was wrong and she was right. She even mocked his soldierly abilities. When the general’s aides suggested that they might install a machine gun at their remote, forbidding country home in Colombey, in case of an attack by communists, Yvonne scoffed that her husband would have no idea how to use it. Perhaps she would have.

Peter Hitchens, “A Certain Idea of France”, First Things, 2019-04.