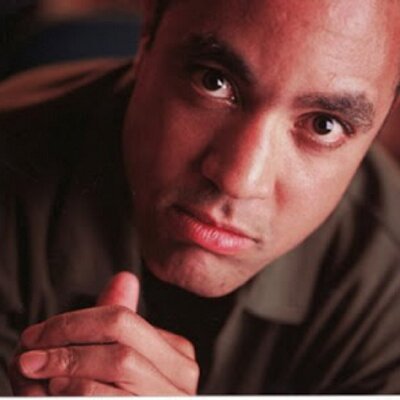

In the latest post at It Bears Mentioning, John McWhorter outlines the history of Affirmative Action in American schooling and explains why it’s no longer doing anything useful and should be re-oriented to actually help disadvantaged students of all races:

I do not oppose Affirmative Action. I simply think it should be based on disadvantage, not melanin. It made sense – logical as well as moral – to adjust standards in the wake of the implacable oppression of black people until the mid-1960s.

When Affirmative Action began in the 1960s, largely with black people in mind, the overlap between blackness and disadvantage was so large that the racialized intent of the policy made sense. Most black people lived at or below the poverty line. Being black and middle class was, as one used to term it, “fortunate”. Plus, black people suffered open discrimination regardless of socioeconomic status, in ways for more concrete than microaggressions and things only identifiable via Implicit Association Testing and the like. In a sense, black people were all in the same boat.

Luckily, Affirmative Action worked. By the 1980s, it was no longer unusual or “fortunate” to be black and middle class. I would argue that by that time, it was time to reevaluate the idea that anyone black should be admitted to schools with lowered standards. I think Affirmative Action today should be robustly practiced — but on the basis of socioeconomics.

A common objection is that this would help too many poor whites (as if that’s a bad thing?). But actually, brilliant and non-partisan persons have argued that basing preferences on socioeconomics would actually bring numbers of black people into the net that almost anyone would be satisfied with.

I’m no odd duck on my sense that Affirmative Action being about race had passed its sell-by date after about a generation. At this very time, it had become clear, to anyone really looking, that the black people benefitting from Affirmative Action were no longer mostly poor – as well as that simply plopping truly poor black people into college who had gone to awful schools had tended not to work out anyway. It was no accident that in 1978 came the Bakke decision, where Justice Lewis Powell inaugurated the new idea that Affirmative Action would serve to foster “diversity”, the idea being that diversity in the classroom made for better learning.

I highly suspect that most people have always had to make a slight mental adjustment to get comfortable with this idea, as standard as it now is in enlightened discussion. Do students in classes with a certain mixture of races learn better? Really? Not that there might not be benefits to students of different races being together for other reasons. But does diversity make for better learning? Has that been proven?

As you might expect, it has not – and in fact the idea has been disproven, again and again. No one will tell you this when the next round of opining on racial preferences comes about. But this doesn’t mean it isn’t true.