Colby Cosh on what might turn out to be the most important US Supreme Court decision in recent history:

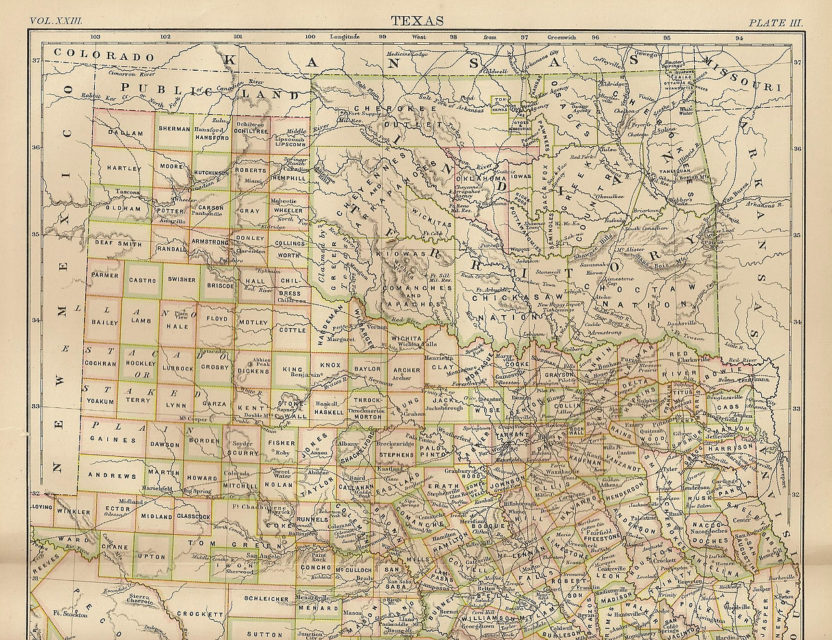

A map of Oklahoma from the mid-1880s showing county boundaries and the tribal areas of Indian Territory.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th edition, 1888 via Wikimedia Commons.

On Thursday the court published its judgment in the case of McGirt v. Oklahoma [PDF]. McGirt is Jimcy McGirt, a man convicted in state court in 1997 of heinous sex crimes against a four year old. A creative public defender had tried to argue for years in lower courts that, as McGirt was a member of the Seminole Nation and his crimes had occurred on territory set aside in the 19th century for Creek Indians, he was never subject to state prosecution.

He should have been tried, the argument ran, under the federal Major Crimes Act of 1885, which specifies that accusations of serious felonies against Indians in “Indian country” go immediately to federal court. Under an 1856 treaty between the U.S. and the Creeks, the Creek lands were to be a “permanent home” for the displaced nation for as long as it existed (at a time when Aboriginal-Americans were still widely expected to diminish and disappear as a race).

The formalized concept of an Indian reservation did not yet exist, but the theory, then and now, is that some Aboriginal nations have direct relationships, albeit ones of “dependence,” with the federal government. Sometimes it is said that the U.S. is the “suzerain,” the overlord, of otherwise sovereign Indian nations. The Creeks, and the other four “Civilized Tribes” who had been forced into the “Indian Territory” that once covered the eastern part of future Oklahoma, were given strong written promises that they would be held apart from the U.S. states proper and would have jurisdiction over crimes and civil matters on their lands. Only the United States Congress, as a power contracting with sovereign nations, could act to encroach upon this jurisdiction.

In a fashion familiar to anyone who has read even a shred of the history of the American Indian, these promises just kind of got … misplaced. In the early 20th century the Oklahoma tribes were encouraged by Congress to abandon communal property holding and take up individual “allotments” of Indian-held land. This ought not to have changed the underlying nation-to-nation relationship, any more than assigning homesteading parcels to settlers busted up or negated the ultimate sovereignty of the U.S. elsewhere in the American West. But that constitutional framework was more easily ignored once a contiguous bundle of territory began to be bought and sold. (Some of it became part of the city of Tulsa.) This history has helped to make similar allotment action in Canada impossible, whatever advantages it might have.