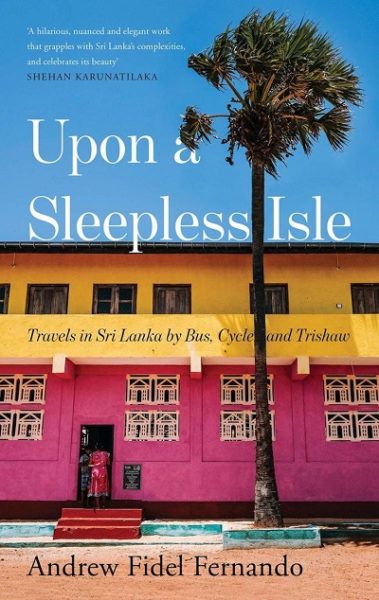

In The Critic, A.S.H. Smyth reviews this Gratiaen Prize-winning travel memoir of Sri Lanka:

Having returned to Sri Lanka from school and uni in New Zealand, and spent a few years consolidating a career in cricket journalism, AFF (as he is also known) decides to tour the country on a solo self-educational adventure – not least because big chunks of it were basically off-limits during his upbringing, thanks to the 26-year civil conflict with the LTTE/”Tamil Tigers”.

The book begins:

The smiles in Sri Lanka are as wide as the horizon, visitors say. The nation’s treasures are as boundless as the ocean, many report. But never let it be forgotten that the ineptitude of the government is as vast and as awesome as the heavens …

At this point, our intrepid would-be traveller just wants the ID card to which he, as a Sri Lankan citizen, is well entitled. But there follow six pages of brutal savaging of the bureaucracy (remember that bear scene in The Revenant …?), and then short treatises on social scandal, unsustainable development, the traffic, tourists, and the glossy travel magazines that bring them here. And we haven’t even left Colombo yet.

But he gets out and about soon enough, and in a punchy 240-page mildly-memoirish survey, utilising pretty much every form of transport barring the bullock cart, he sees the elephant herds at Minneriya, climbs the 1/8-Mile-High Club that was the rock fortress of Sigiriya, explores a highwayman’s hideout near Kandy, the surreal Lego-ish hill town of Nuwara Eliya, the tea estates, the ancient waterworks around Polonnaruwa, the temple-strewn Anuradhapura, the otherworldly Mannar island, the Southern beach towns, and on through the flattened LTTE heartlands up into Jaffna. (Cricket nerds, be advised: there is no cricket in this book.)

In all, his journey amounts to about seven or eight weeks on the road, and, Sri Lanka being a fairly small place, it’s worth noting that his is an entirely normal tourist itinerary – a visitor with even a mid-level budget and modest accommodation demands could cover all of it in a three-week holiday – just done more slowly and, crucially, with better local “access”, specifically linguistic.

Like all good “city-bred pansy” writer types, he gets into scrapes (a tuktuk crash), and makes a fool of himself (“helping” some fishermen), and the whole thing is narrated with much irreverent humour and ironic side-eye, topped off with a great line in exaggerated street-chat/aunty gossip and the occasional murderously-deft flick of the stiletto: “if you had the financial means to inspire a government worker out of apathy …” – all facets not exactly over-represented in Sri Lankan English letters (non-fiction, anyway. Novels are full of it).

Nor is his apparent economy dependent on foreknowledge on the reader’s part (aided certainly by the author’s more-or-less ingenuous exploratory conceit). Whatever learning AFF was already armed with here is lightly worn, he works in the historical and social context of each leg of the journey with a minimum of fuss (a certain journalistic pragmatism and efficiency paying off there, one assumes), and there’s really no time at which you feel he’s had to throw his bucket down the well of Wikipedia to get through to the end of a particular informative sub-section.

That said, considerable amounts of this material were new to me (which, in a whistlestop tour of the entire island, is not saying nothing). His trip to the abandoned rebel-descendant jungle village of Kumana is as intriguing as the details of the 1817 Uva rebellion are grim. And in particular, I’m grateful to him for introducing me to the life and works of the archaeologist John Still, and clueing me up as to the origin of the phrase “white elephant”: “after the Thai royal practice of presenting unpopular courtiers with tuskers that were ruinously expensive to maintain.”

Alas for AFF – the curse of writing first-draft history – Upon a Sleepless Isle also offers (or rather offered) two major hostages to fortune. Namely, his repeated and overt enthusiasm about the transition away from the family-oriented regime of Mahinda Rajapaksa (2005-15), and his vocal sympathy and support for Sri Lanka’s peaceful and tolerant Muslim minority. Only three months after the book was published, a series of domestic Muslim terrorist attacks took place around the country, killing hundreds, which in turn helped to usher in the present (Gotabaya) Rajapaksa government. These have aged almost so badly that it adds a certain piquancy to read his already-blasted hopes of just two years ago.