In the latest edition of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention newsletter, he looks at the predictions of that old gloomy Gus, Thomas Malthus:

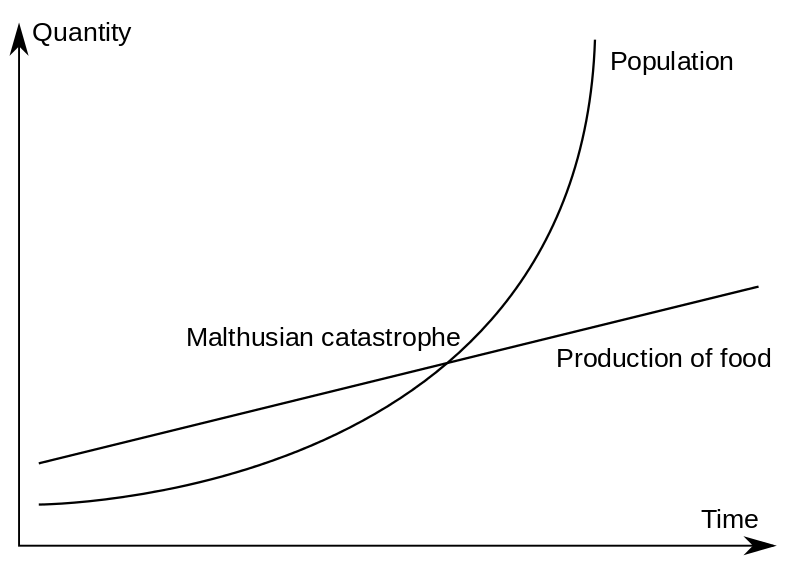

The Malthusian trap. For Malthus, as population increases exponentially and food production only linearly, a point where food supply is inadequate will inevitably be reached.

Graph by Kravietz via Wikimedia Commons.

For economies before the Industrial Revolution, population growth was an important and ever-present brake on prosperity — an observation most famously articulated by the Reverend Thomas Malthus. Writing at the end of the eighteenth century, he warned against the promises of improvement. Whereas the optimists looked at the acceleration of innovation around them and claimed infinite horizons for increasing living standards, Malthus pessimistically argued that population would always catch up. Although a new agricultural technology might briefly increase the amount of available food, the inexorability of population growth meant that it would soon be eaten up by extra mouths to feed. The population would end up larger than it was before the new technology, but with that population eventually no richer than it had been to begin with. Economic historians call this the Malthusian regime, or the Malthusian Trap.

Fortunately, Malthus’s pessimism would prove unfounded. Economy after economy has managed to escape the trap. British output had already been outpacing its population for two centuries by the time he was writing — England’s agricultural output alone had increased 171% while its population had grown 113% (not even taking into account the fact that it also increasingly relied on imported food, paid for by its other industries). And in the decades and centuries that followed, England’s output continued to shoot ahead, widening the lead. Output per capita rose and rose, to the extent that Malthus’s worries about overpopulation are now usually applied to resources other than food.

But while Malthus is famous for the theory, he wasn’t its inventor. Well before Malthus, the people who actually lived in the trap seem to have recognised its effects. Concerns about overpopulation may have led to the Garland or Flower Wars of the Aztec Empire and its neighbours: after a series of famines in the 1450s, the local states reportedly began to engage in ritual battles, with the losers captured and sacrificed to the gods. Still earlier, in ancient Greece, the young men of a settlement might be formally conscripted to go forth and colonise other islands and coastlines. They were typically banned from returning home for several years, and in at least one case slingers were posted on the shore to kill any of the colonists who tried to make a break for home. In a whole host of pre-industrial societies, “surplus” infants were often simply exposed to the elements.

By the sixteenth century, with the rise of print culture, Malthusian rationales were being clearly articulated. Here’s Richard Hakluyt writing in 1584, over two hundred years before Malthus:

Through our long peace and seldom sickness (two singular blessings of Almighty God) we are grown more populous than ever heretofore; so that now there are of every art and science so many, that they can hardly live one by another, nay rather they are ready to eat up one another.

It’s a direct statement of the Malthusian regime in action, expressed by one of England’s most influential Elizabethan intellectuals, and written specifically for the attention of the queen. Hakluyt thanked god for the recent and unusual lack of mass death, but now worried about overpopulation leading to low wages and unemployment. And he went on to list many other effects. Hakluyt argued that the misery would lead to unrest, thievery, begging, and “other lewdness”. The prisons filled up, where the poor either “pitifully pine away, or else at length are miserably hanged.”