Theodore Dalrymple relates the rather odd story of a young girl’s media-publicized objection to a math problem in school and then considers the girl’s given name in the larger context:

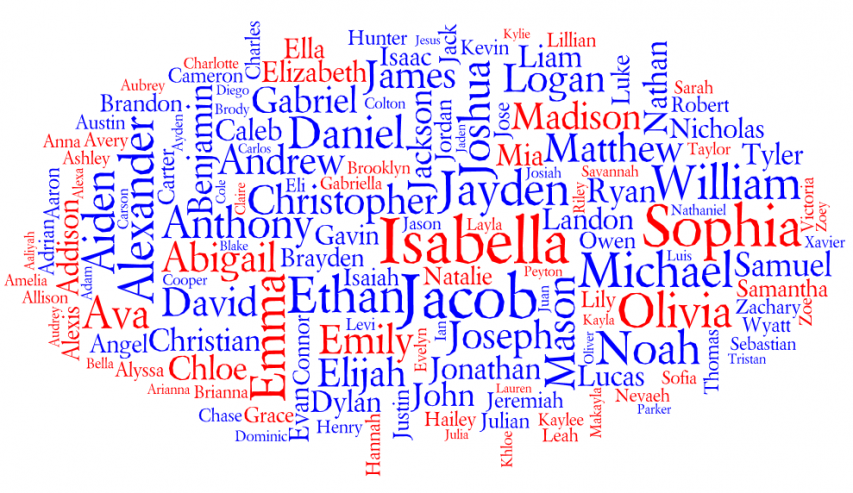

My attention was also caught by the first name of the politically-correct child: Rhythm. This is not a traditional name, though not actually ugly; but her parents have evidently accepted the increasing convention of giving a child an unconventional, and sometimes previously unheard of, name. This is a worldwide, or at least occident-wide, phenomenon. In Brazil, for example, parents in any year give their children one of 150,000 names, most of them completely new, made up like fake news, and in France, 55,000 children are born every year who are given names that are shared by three or fewer children born the same year. This latter is all the more startling because, until 1993, there was an old Napoleonic law (admittedly not rigidly enforced) that constrained parents to choose among 2000 names, mainly those of either saints or classical heroes.

What does the phenomenon of giving children previously unheard-of names signify — assuming that it signifies something? I think it is symptomatic of an egoistic individualism without true individuality, of self-expression without anything to express, which is perhaps one of the consequences of celebrity culture.

I performed an internet search on the words Rhythm as a given name. I soon found the website of a group called the Kabalarians, who believe that the name given to a child determines, or at least contributes greatly, to its path through life, especially in conjunction with the date of birth:

When language is used to attach a name to someone this creates the basis of mind, from which all thoughts and experiences flow. By representing the conscious forces combined in your name as a mathematical formula, one’s specific mental characteristics, strengths and weaknesses can be measured.

It invited readers to inquire about the psychological characteristics and problems of people with various given names. I invented a child called Rhythm of the same age, more or less, as Rhythm Pacheco. This was the result:

The name of Rhythm causes this child to be extremely idealistic and sensitive. She will find it difficult to overcome self-consciousness and to express her deeper thoughts and feelings in a free, natural way. She is too easily hurt and offended, and will often depreciate her own abilities. Because of her lack of confidence and her sensitivity, she will go to great lengths to avoid an issue. True affection, understanding, and love mean a great deal to her, as she is a romantic and emotional youngster. Often she will resort to a dream world when her feelings are hurt. She could be very easily influenced by others, for she will find it difficult to maintain her individuality. This problem could become more predominant during the teenage years. Although there is much that is refined and beautiful about her, the lack of emotional control could bring much unhappiness, repression, misunderstanding and loneliness later in life. Tension could also create fluid and respiratory problems. Because of the sensitivity created by this name, she will find it difficult to cope with the challenges of life.

There is, in fact, a semi-serious theory of nominative determinism, according to which a name may influence a person’s choice of career: two of the most prominent British neurologists of the first half of the twentieth century, for example, were Henry Head and Russell Brain. A recent Lord Chief Justice of England was called Igor Judge. And surely it must work in a negative direction too: no poet could be called Albert Postlethwaite. However rational one believes oneself, one might also experience a frisson of fear on consulting a doctor called Slaughter — as was called the doctor and popular novelist Frank G. Slaughter.

When I first went to Africa, I encountered patients whose first names were Clever, Sixpence or Mussolini. The first of these names was presumably an instance of magical thinking, while the second two were chosen merely because the naming parents liked the sound of them. Years later, during the civil war in Liberia, I met a constitutional lawyer called Hitler Coleman, who presumably desired to live his name down by concerning himself with the rule of law.