Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-2-edited/1434).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Marc Milner picks up the story in North Atlantic Run:

The first year of the war at sea developed as Allied planners had anticipated. Germany’s U-boat fleet was small and remained so. Its operational strength of forty-six submarines (only twenty-two of which were capable of deep sea work) was far short of the three hundred U-boats that Rear Admiral Karl Dönitz, Befehlshaber der U-boote (BdU; commander-in-chief of U-boats), estimated he needed to sever Britain’s supply lines. Moreover, the U-boat fleet was initially circumscribed by Allied control of the exits from the North Sea. In the early months of the war U-boat captains generally obeyed their strict instructions not to anger neutral opinion through rash and illegal acts, despite their torpedoing of the liner Athenia on the first day of the war, which suggested that Germany would again adopt unrestricted submarine warfare. So the Allies concentrated on Germany’s powerful surface fleet, on her commerce raiders lurking in disguise on the oceans of the world, and on hapless offensive anti-submarine (A/S) sweeps.

The convoys were organized from the first days of the war and had some escort vessels, but the U-boats were not yet operating at full potential — this would become blatantly evident later — and the relatively few escorts were not hard pressed to keep the merchant ships safe in passage.

S.S. Athenia, at Montreal in 1933. She was torpedoed on the very first day of World War 2 by U-30 northwest of the coast of Ireland. Of the 1,103 passengers and 305 crew aboard, 118 were lost in the sinking (including 28 Americans).

Clifford M. Johnston / Library and Archives Canada / PA-056818

Through the spring and early summer, the U-boats operated mainly between Britain and Iceland; while they achieved nothing spectacular in terms of Allied tonnage sunk, the escort ships scored few victories in return. In one three-hour hunt HMCS St. Laurent and the RN destroyer Viscount dropped 80 depth charges in attacks on a submerged U-boat; when diesel oil bubbled to the surface they were sure they had gotten a kill. The Admiralty, cautious to award kills even in the early days, credited them with a “probable”.

Although Germany was now able to make good use of well-sited and easily defended new submarine bases on the Atlantic coast of France and to begin developing new tactics, it did not shake Allied belief that the U-boat threat had been rendered ineffective by ASDIC, convoys, and airpower.

Indeed, in a book on Modern Naval Strategy published by Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, RN, and F.E. McMurtrie, two well-respected naval theorists, submarine attack on an escorted convoy was given little chance of success. Supposing the submariner could find the convoy in the first place, his distorted view of the world through a periscope was considered a grave handicap. With a periscope exposed in broad daylight — the only time, the authors believed, that an attack was possible — the submarine invited swift retribution from both escort and merchant vessel alike. Moreover, it was still generally believed that once a submarine was locked in ASDIC’s grip, destruction would follow from carefully placed depth charges. This view of anti-submarine sarfare (ASW) was utterly shattered by the Germans’ resourceful use of the U-boat in the second winter campaign on the sea lanes.

In practice, ASDIC was nowhere near perfect, and neither was depth charge placement especially when employed by Canadian escort ships — the inexperience of the majority of Canadian sailors played a role, as did their older and less sophisticated ASDIC sets. There were not enough escorts to protect convoys against multiple attackers, and air power was only available close to land and it proved not to be as capable as the Allied planners had hoped.

Air assets were so rare that the later war “mid-Atlantic air gap” did not exist because few of the necessary air bases that would be built by the end of the war were in place or even under construction yet. Canada’s pre-war air force was small, and though it was growing rapidly, it was not equipped or trained for ASW. The RAF had needed almost every available pilot during the Battle of Britain, and many pilots had been killed or wounded. Germany continued to build more U-boats, building at a far faster pace than Allied ASW forces could sink them, and now with far greater deployment flexibility than they had enjoyed during the First World War.

Marc Milner discusses the RCN’s expansion woes:

Fundamental to the whole problem of expansion was the availability of ships, and here too the RCN’s plans in the early days were never reliable. To upgrade local defences, to replace decrepit auxiliary vessels, and to provide A/S “strike forces”, the RCN had to undertake a modest shipbuilding program beyond that proposed in the pre-war plans. To round out local defences and the like it was decided in early September 1939 to build Bramble-class sloops and a small number of minesweepers. Further consideration was also given to the acquisition of Tribal-class destroyers. But the coming of war so early in the navy’s planned expansion threw it into serious disarray. Tribals could not be built in Canada without considerable assistance from British firms, and with British industry now fully absorbed in war work little help could be expected. Unfortunately, the RCN rejected a very sensible British suggestion that it seek expertise in naval ship construction in the United States. The Canadian navy also failed, initially, to obtain permission to place orders for Tribals in British yards. Faced with an almost impossible dilemma, the Naval Staff hit upon the idea of bartering less-sophisticated Canadian-built warships for British-built destroyers. The scheme had all the advantages of specialization. It permitted Canada to turn products from less-skilled manufacturers into high-value, long-term investments. For the government it meant good business and the possibility of future orders. For the RCN it meant the fulfillment of its expansion plans.

HMCS Cartier, later re-named HMCS Charny, in October 1940. An old Canadian Hydrographic survey vessel from 1910 pressed into service. Used for Naval Training and Naval Mine Avoidance Navigation.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-104169As the Naval Staff sorted through the problems of destroyer acquisition, it also tackled the question of what type of auxiliary warship to build for its own purposes and what type to build for bartering. Initial hopes of building sloops were dashed by the news that Canadian yards were incapable of building even small warships to naval standards. As the problem was being discussed, basic plans for a much simpler auxiliary ship arrived at Naval Service Headquarters (NSHQ) from the National Research Council (NRC), which had acquired plans for “whale-catchers” in July during a fact finding trip to the UK. The whale-catchers immediately appealed to the Naval Staff as a workable substitute for sloops, given that they were intended to be auxiliary vessels for inshore duty. Moreover, their mercantile construction was ideally suited to Canadian yards, and British adoption of this class made them suitable for bartering.

Once agreed that corvettes (as the whale-catchers were called by early 1940) were to be built as the navy’s primary A/S ship and as the means whereby larger vessels might be acquired, the Naval Staff had to decide how many to produce.

[Editor’s Note: The development of the corvette goes back to a WW1 proposal for a submarine-hunting ship based on the design of whaling ships. In 1936, Smiths Dock Company of Middlesbrough built the whaling ship Southern Pride (displacing 700 tons, with a top speed of 16 knots), and eventually the design was adapted into a naval escort, the Flower-class corvette, that became the backbone of the convoy escort fleet. I’ve always been fascinated by the Flowers, as they originated in my home town and my maternal grandfather worked for Smiths Dock throughout the war as a plater (he very likely worked on several corvettes in that time). In War at Sea: Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, Ken Smith provides this description:]

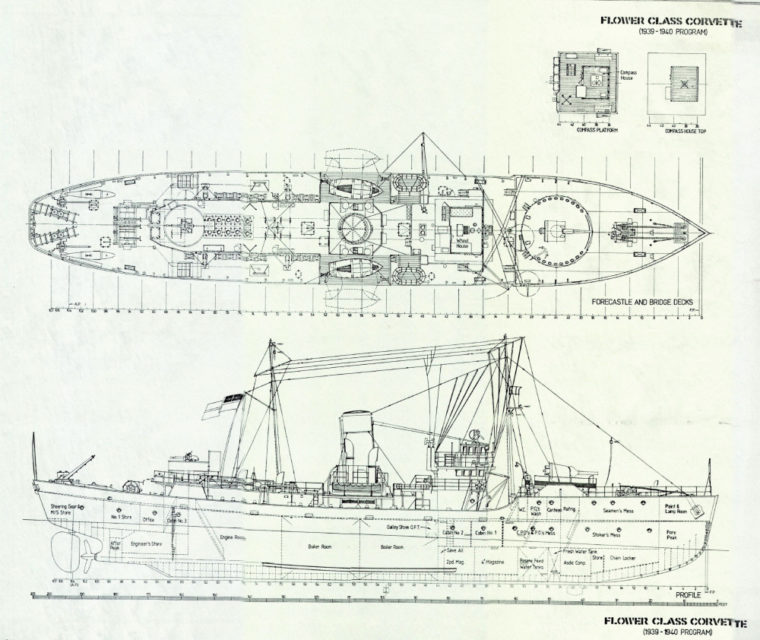

Diagram of the early Flower-class corvettes, via Lt. Mike Dunbar, RN (https://visualfix.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/dreadful-wale-4/)

The Royal Canadian Navy … had originally planned to build its own naval fleet with destroyers and larger ships, but it quickly became apparent that smaller ships were needed to protect major Atlantic ports and naval facilities, and to allow merchant shipping traffic sufficient convoy protection. It was imperative that some sort of small, speedy vessel with anti-sub competency be built and put into use as soon as possible. Corvettes were only intended for use until the larger and better-equipped destroyers and frigates were made available from the British shipyards. …

British shipbuilders at the Smiths Dock Company came up with a design based on a successful whaling ship which could be constructed cheaply in Canada. Thus the corvette was born, untested and unaware that the outcome of the U-boat challenge in the Battle of the Atlantic would rest heavily on its performance. Approximately half of the first order of corvettes produced were used as convoy escorts and over twenty of these workhorses were lost to German subs, but by the end of the war they had effectively proved their worth time and time again.

The name corvette, given to the short, wide-beamed ship by Winston Churchill after a small sailing ship of old, was deemed superior to the original name, the Patrol Whale Catcher. But the RN and RCN had ships in production by 1939*, albeit with slightly different designs. With a length of 205 feet and a 33-foot beam, the small ship was relatively slow at 16 knots, but could turn inside any other ship available. With moderate firepower, including a 4-inch bow gun, a pom-pom gun, several Lewis machine guns, depth charges, and later, Hedgehog equipment, the corvette proved able to tackle the roughest seas. But, as expected, there were shortcomings. They were considered “wet ships”, their decks often awash with water as they rolled, bucked, swerved, and veered violently, with even hardened sailors becoming sea-sick at times.

* This is not quite correct. The first Canadian corvette wasn’t laid down until 2 February, 1940, according to the list of Canadian Flower-class corvettes at Wikipedia.

[Editor’s Note: The armament could vary, depending on what the RCN could scrounge from its own resources or cadge from the Royal Navy:]

HMCS Trillium, first of the Canadian-built Flower-class corvettes to be completed.

Photo from the Naval Museum of Manitoba, via Wikimedia Commons.

Armament consisted of a 4″ gun on the bow and (if they were lucky) a 2pdr Pom-Pom in a bandstand aft, this was initially rounded off with a pair of Lewis machine guns on the bridge. Many went to sea with a quadruple .50 machine gun mount in place of the 2pdr, and many more Royal Canadian Navy Flowers originally mounted a pair of twin .50s in this position. Eventually 20mm Oerlikons replaced the bridge guns. These early Flowers looked very much like quaint little merchantmen masquerading as warships with their short focsle, merchant type bridge, large vents around the funnel and on the engine room casing.

In The Corvette Navy, James B. Lamb explained why the decision to go with “old fashioned” engineering solutions turned out to be a very good idea in the long run:

Driven by a single three-bladed propeller, she was to have a maximum speed of 16 knots and a really remarkable endurance of 4,000 miles at 12 knots on only 200 tons of oil fuel. Her machinery — four-cylinder triple-expansion reciprocating engines of 2,750 horsepower, and twin cylindrical Scotch boilers — was deliberately kept simple, for ease both of manufacture and of operation, and the whole design was intended from the beginning to be capable of production by every sort of engineering firm other than the big shipbuilders, which were now crammed to capacity with large warship orders. […] But all unrecognized in these plans was a touch of genius; the dowdy maid-of-all-work had been endowed by her Good Fairy with a wholly unexpected range of qualities. For this ship of humble design proved to be capable of amazing versatility, able to carry more than twice her designed complement and a seemingly endless accumulation of ever more sophisticated armament and instrumentation. She could keep the sea in weather that overwhelmed huge merchant vessels and reduced destroyers to water-logged hulks; she could be used for anything from minesweeping to anti-aircraft protection. But, greatest blessing of all, she could turn on a dime, the only Allied warship with a turning circle tighter than that of a submarine, and in consequence she was the master of the U-boat in manoeuvring duels that would foil any other surface escort.

Adaptable and flexible in an ever-changing war, the corvette became the backbone of the Allied escort force, going through endless modification and improvement in the course of the building of no fewer than 269 ships, the largest warship class ever built.

Ultimately she evolved into a new class; two sets of corvette engines were jammed into a lengthened corvette hull to gain a little more speed, and the resulting super-corvette was called a “frigate”. By the war’s end, frigates and corvettes made up almost the entire strength of the Allied escort forces in the Atlantic, and their crews of reservists had brought the techniques of convoy escort and submarine detection and destruction to new heights of expertise.

And on the naming of the Flower-class ships themselves:

Right from the beginning, there was something suspect about corvettes in the eyes of right-thinking professional navy men; what was one to make of a man-of-war that looked like a fish trawler and called itself HMS Pansy? For the Admiralty, in a moment of inspiration, had designated the new ships as the Flower class, a tradition in escort vessels begun in the First World War. Each Royal Navy corvette was named after a flower, and the world was enriched by sea-stained fighting ships glorying in the name of His Majesty’s Ship Pennywort, Crocus, or Tulip. There was a Convolvulus, a Saxifrage, and a Cowslip. But even a Board of Admiralty has a heart; eventually HMS Pansy was allowed a change of name by a repentant Ships’ Names Committee. She became HMS Heartsease.

By the time the Royal Navy had built more than a hundred corvettes, flower names were becoming difficult to come by; HMS Bullrush probably reflects the growing desperation of this latter period, while HMS Burdock and HMS Ling show just how far the naming committee was prepared to cast its net. In Canada, HMCS Poison Ivy was openly conceded to be a possibility, but cooler heads prevailed; the Canadians decided to name their corvettes after towns and villages, although a handful of flower names — Spikenard, Snowberry, Windflower, etc. — were incorporated with ships originally built for the Royal Navy but taken over by the RCN.

It was widely believed in the wartime Allied navies that the naming of the Flower class was part of a form of psychological warfare practised on the enemy by a vengeful Britain; there must be an added [ignomy], it was felt, to being sunk by HMS Poppy, as U-605 was, or to being outfought and captured by a fierce HMS Hyacinth, as was the Italian submarine Perla. It was one thing to perish in the Wagnerian splendour hankered after by Hitler, but quite another for the proud Teuton to be vanquished by Rhododendron, as U-104 was, or sunk by Periwinkle, like U-147.