Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-1-edited/1433).

Sources:

- The Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

On August 26, just a few days before the official outbreak of war, a single word Admiralty telegram was received in Ottawa from London: FUNNEL. With that message all British merchant vessels passed under Admiralty control. The same transfer took place in Canada on the same day. No Canadian-registered ship, no merchant ship in any Canadian port could sail without the authority of the Royal Canadian Navy. Naval control officers faced an enormous task. All British merchant vessels in North American waters would have to be gathered in from the wide face of the sea, assembled, bunkered, stored, provided with codes and orders. Vessels of every type would have to be formed into orderly fleets, sailed at precise times and by specified routes with the precision of a crack railway, all in absolute secrecy. Halifax stirred once again with the grim vitality of a key port in a world at war. Ships put in, their schedules interrupted, their captains angry, demanding explanations they didn’t get. Painting parties descended to defile clean white ships with the drab gray of military vessels. Old naval guns were mounted on merchantmen and a few ships were issued machine guns.

[Editor’s Note: Unlike the Royal Navy’s comparatively vast administrative resources for organizing convoys, the RCN had to draw heavily upon a small number of retired RN and RCN officers living in Canada and the United States to gather enough officials to establish convoy control in Canadian ports (the same pool would also be used to recruit convoy commodores). It’s difficult for modern readers, used to networked computers with online databases, to realize just how much literal paperwork had to be created and maintained from scratch to even begin organizing the convoy system from North America to the UK: that it was done at all is amazing. That it was done about as well as could be hoped is incredible.]

Ratings mustered along the starboard side of HMCS Assiniboine at sea, ca. September 1940.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-104105

On August 31st HMCS Fraser and St. Laurent were re-deployed to the east coast from the west coast.

On September 16th, six days after Canada declared war, the destroyers St. Laurent and Saguenay moved out through the Halifax approaches. Following behind were the 18 merchant ships of convoy HX-1, Halifax to the UK. Awaiting them offshore were the Royal Navy cruisers HMS Berwick and HMS York. The crossing was uneventful, but these 18 were the first of a grand total of 25,343 merchant vessels that would sail from North America under Canadian escort.

To briefly discuss the convoy system itself, it’s fairly simple: merchant vessels sail in organized groups rather than on their own and are provided some form of naval escort to protect them from hostile vessels. Even lightly guarded convoys are immensely preferable to ships sailing on their own, reducing the width of the target area and forcing any potential attacker to weigh the risk of counter-attack by the escorts. [Editor’s Note: It may seem odd to landlubbers like most of us, but even a large convoy is not much easier to find than a single ship in the wide ocean. Fewer discrete targets requires more search time by enemy submarines and surface raiders.] The speedier the convoy, the better, but the limited speed of many of the merchant ships necessitated a system of fast and slow convoys with different starting points in the Americas, and different codes for identification. The merchant vessels are described by Alan Easton, captain of the corvette HMCS Baddeck in 50 North: Canada’s Atlantic Battleground [Easton’s book is factual in most ways except for the dialogue and some of the names being changed]:

We sailed to Sydney, Nova Scotia. There we spent the night, topped up with fuel and stood out of the harbour early the next morning, where we were to await the convoy we had been instructed to escort. Many ships were lying at anchor that morning in the fine, land-locked harbour, ships of numerous different Allied and neutral nations, for this was the assembly port for the eastbound slow Atlantic convoys in those days. As we moved back and forth off the harbour mouth, I fell to examining the ships as they came out, one behind the other at intervals of three or four minutes, led by the Commodore’s ship. It was always intensely interesting to me to gaze at the ships. The more weatherbeaten and decrepit the ship, the more attractive she was to me; she had a story to tell and I could sometimes discern a part of it by just looking. The newest might have been ten years old, the oldest perhaps forty or fifty. Some were built of iron — the inch-thick plating of the 1880s, before the days of steel. They were large and small, from about nine hundred tons to nine thousand. You could tell almost at a glance their nationality, or the country in which they were built, by the shape of their hulls and the construction of their upperworks. But as they came out they flew their ensigns, soon to be hauled down, so that you could not mistake their identity. They were all heavily laden, few that were not down to their Plimsoll marks and some with little freeboard, perhaps four feet between the water and the well deck.

The first ship moved slowly, marking time as it were, to allow the others to take their stations, so that the whole could form into three columns. Soon after noon, the Commodore seemed to be satisfied that all were in their correct places for he ran up a flag hoist indicating that the speed of the convoy was to be seven knots. When every ship had signified that she understood his signal, the Commodore hauled his flags down and the engines of this heterogeneous collection of vessels simultaneously moved faster, although to the onlooker there was no perceptible change in speed.

The fast/slow system was implemented fairly early on, and by August 1940 slow convoys were more often being formed in Sydney, Nova Scotia, the faster convoys in Halifax. By 1941, fast convoys left every six days and made the crossing in around 13 to 14 days. Slow convoys left every six days as well, but took 16 to 17 days to cross. The size of the convoys varied. The largest convoy to ever make the crossing was HXS-300 consisting of 167 ships, but a good benchmark was 40 or so merchant vessels. These ships are positioned in a grid with nine columns, 920 metres apart, and in each column five ships, 550 metres apart. Ships carrying dangerous cargoes, such as gas, fuel, or explosives are placed in the centre, the position that affords the most protection against enemy torpedoes. The convoy commodore, in most cases a retired naval officer, is on board one of the merchant ships to take defensive measures as required and ensure coordination with the escort.

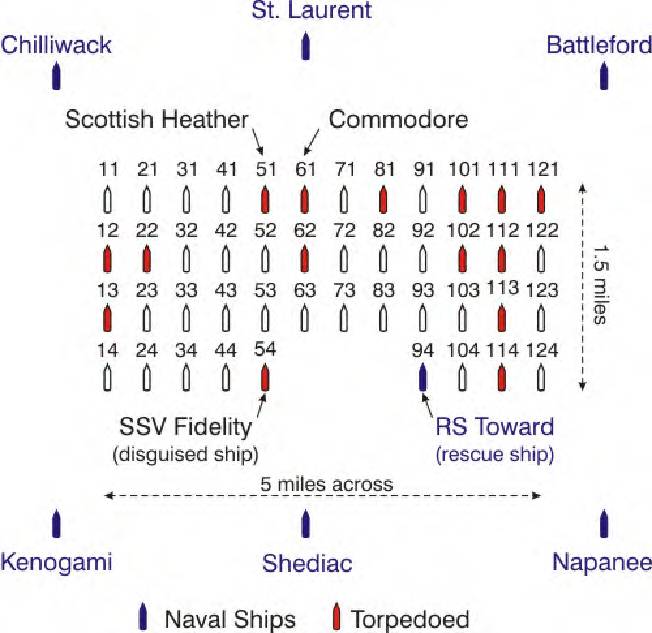

[Editor’s Note: An image from Swansea Docks showing the schematic arrangement of slow convoy ONS-154 returning to Halifax later in the war:]

Convoy ONS-154 in December, 1942. The numbers indicate the column and row designations for each merchant ship in the convoy.

Image by Ron Tovey, Swansea Docks – click the image to visit his site.

The following system of codes was used for identification of trans-Atlantic convoys:

HX: Fast convoys (9 knots or over) sailing from Halifax (or later New York)

SC: Slow convoys (under 9 knots) sailing from Sydney, Halifax, or New York

ON: westbound convoys sailing from Great Britain to North America

ONS: slow westbound convoys sailing from Great Britain to North America

The following system of call letters was used for identification of coastal convoys:

BX: Boston to Halifax

XB: Halifax to Boston

SQ: Sydney to Quebec City (via the St. Lawrence River)

QS: Quebec to Sydney

Convoy forming in Bedford Basin, 1 April, 1942

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-112993

There was much debate among Canadian politicians as to the role Canada would play in the war in general. In the first few weeks, much debate was had as to which services would receive what money, and how they would be integrated into the allied war effort. Prime Minister Mackenzie King had somewhat sold the war to the nation as being different from the last war [Editor’s Note: where Canada provided an over-strength army corps for the Western Front, suffering nearly 60,000 combat deaths, slightly more than the US combat losses in that war]. Finance Minister J. L. Ralston publicly envisaged a program that would be “practical rather than spectacular”. The Prime Minister spoke of protecting Canada by sending food and raw materials to Britain and building a navy and air force and munitions industry, even the first musings of what would become the BCATP [British Commonwealth Air Training Plan] (though these early plans paled in comparison to what it would eventually become.) Canada would contribute vast amounts of resources to the allied cause, but there was not going to be a need for a large land army to fight and die in Europe. The army was just as short of equipment as the navy was and the air force consisted of 3100 men and 270 mostly obsolete aircraft, with just 19 modern Hurricanes. The old issue of conscription that had led to riots in Montreal in 1917 immediately reappeared, and an important provincial election in Quebec had been called within two weeks of the declaration of war in almost direct response to it. [Editor’s Note: The risk of another conscription crisis haunted the Canadian government from the very start of the war: English Canada was heavily in favour, but Quebec was just as opposed, and the ruling Liberal Party couldn’t risk losing their support in Quebec.] What soldiers Canada did have departed Halifax as part of convoy TC-1 in early December, and by the end of the month Canada had 15,000 men in England (the 1st Canadian Infantry Division).

It is the opinion of my sources that the idea of a limited war were extremely favorable to the navy and air force in the early months. Canadian naval vessels and aircraft fighting alongside the United Kingdom was seen as an appropriate contribution, whilst at the same time, seen as far less costly in terms of lives than a large expeditionary army, which Mackenzie King was steadfastly opposed to (fear of conscription crisis was ever present). Canada’s merchant fleet was at Britain’s disposal without question, combined with the vast natural resources she could provide, quite nicely rounded out the “limited war” concept. Industrial military capacity was small, almost non-existent, and building ships, aircraft and munitions would help it grow.

Focusing specifically on the navy itself, what few ships it had were immediately deployed on patrols and put to work escorting coastal convoys within coastal waters, and trans-Atlantic convoys to a handover point mid-voyage. The reserves were activated and sent to the coasts. In November all the Canadian destroyers were placed under the command of the Royal Navy’s North America and West Indies station (somewhat to the Government’s dismay, although not the navy’s: most RCN officers had close peacetime ties to the British squadron and felt it was the natural choice. They had actually requested this at the start of the war and had been refused by the government, who wanted the RCN’s ships kept close to home.) This placement also had the benefit of assuring the RCN that they would participate in the types of operations they had trained for; fleet work, or sweeps for surface raiders. October 1939 saw the purchase of a another destroyer, re-named HMCS Assiniboine in Canadian service. These seven River-class destroyers would form the backbone of the navy well into 1943. A modest attempt had been made in 1938 to give Canadian yards some experience building warships with a minesweeper program. Despite the dispersal of the contracts to both Atlantic and Pacific yards for four Fundy-class minesweepers, the Canadian shipbuilding industry was unprepared for the demands wartime was to make of it.

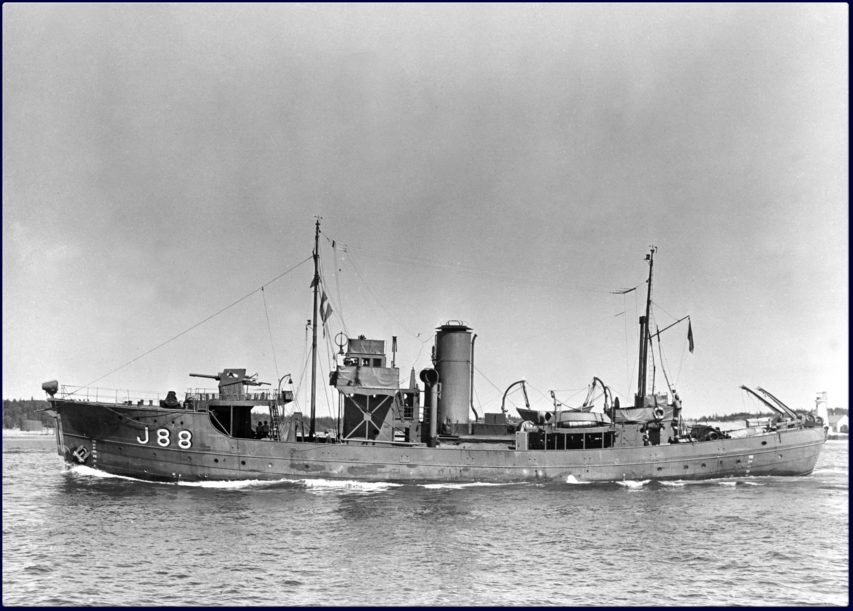

Undated photograph of RCN minesweeper HMCS Fundy (J88).

Canadian Navy Heritage website. Image Negative Number NP-1404 via Wikimedia Commons.

In North Atlantic Run, Marc Milner discusses the Ottawa front of the RCN’s early wartime struggles:

In the government the navy actually had a friend, as it discovered when planners began to submit estimates for expansion. As the late Admiral L.W. Murray, RCN (in September 1939, the Director of Operations and Training) recalled, the navy was given a carte blanche to plan its growth over the succeeding four or five years. When in February 1940 Murray and the deputy minister presented the first wartime naval estimates before the Finance Committee of the cabinet, they passed despite a “fine-tooth comb” inspection. The fact was that the navy’s expansion and its attendant shipbuilding programs suited the government’s intention to profit from what was seen as a limited European war. The prime minister, W.L. Mackenzie King, was steadfastly opposed to fielding yet another large army in Europe, which might lead to high casualties and a call for conscription. Rather, his government sought to channel Canada’s war effort into the sinews of war and into much less personnel-intensive services such as the air force and the navy. Both of these services also offered excellent opportunities for the development of Canadian industry.

The link between industrial and naval expansion also went deeper than simply the building of ships. In July 1940, the expansion of the navy was given impetus by the appointment of a separate minister of Defence for the Naval Service. King chose Angus L. Macdonald, former premier of Nova Scotia. Although once rather uncharitably described as “lightweight”, Macdonald was extremely popular in his home province and a strong voice for Nova Scotia in Ottawa. Macdonald and two other prominent Nova Scotians, Colonel J.L. Ralston, the Minister of Defence, and J.L. Ilsley, the Minister of National Revenue, formed the right wing of King’s cabinet — what J.W. Dafoe called the “Tory Imperialists”. All supported a full war effort, a position that led in 1944 to a bitter break between King and the two defence ministers over the issue of conscription. But apart from Macdonald’s desire to see Canada fully represented at the front, he shared many of King’s beliefs, including the notion that the preservation of the free world depended upon the retention of power in Canada by the Liberal Party.

Macdonald also believed that Canada could and should progress industrially from the war. Long a crusader for the re-industrialization of Nova Scotia, he saw an opportunity to funnel some of government investment into his own province. There was, moreover, a direct link between industrial growth and a large navy. “What use could it be to increase our agricultural production … or to put forth the magnificent industrial effort that we have,” Macdonald asked in 1945, “unless this food and these munitions could be got safely across the sea?” Although in the end he failed to restore to Nova Scotia its past lustre, this was precisely the rationale used to justify building destroyers in Halifax during the war. In the most fundamental sense, then, the aspirations of the [full-time, professional] navy and the government coincided.