The Great War

Published on 1 Oct 2018In this episode of Out of the Ether, we read a few excellent comments about WW1 Trucks and the Palestine Front.

October 2, 2018

Stories From The Palestine Front – More About WW1 Trucks I OUT OF THE ETHER

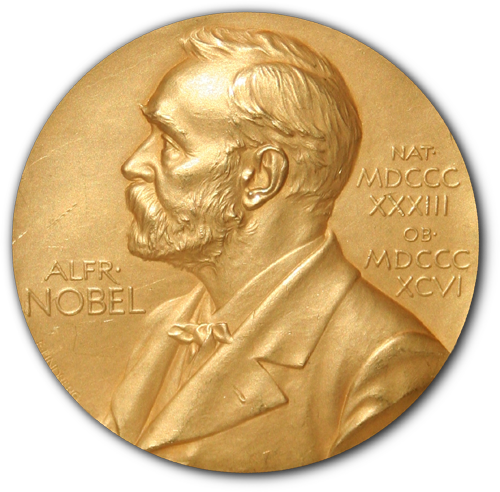

It’s time to “fix” the Nobel Prize system, because reasons

Tim Worstall on the demand that the Nobel prizes be awarded more “equitably”:

We have a nice example of the standard left wing perniciousness here with this complaint that the Nobels have to be changed because reasons. The pernicity being that instead of doing the honourable thing – go off and create your own – the demand is that an extant part of society be coopted into the Borg and run as those who didn’t create it insist. We do rather see this all around society, don’t we? Google’s search functions must operate as the social justice warriors insist, Facebook and Twitter must not allow anyone not on message to ever say anything publicly, Nobels must be awarded for environmental sciences. And to women. And groups. And as we insist, dammit!

Why Nobel prizes fail 21st-century science

After all, something that’s been around a century and more, gained vast repute by being so, cannot be allowed to continue untamed, can it? That would just be so conservative! Leave this sort of thing alone and people might even think the nuclear family is a pretty good idea. Or clans, tribes, or something.

But many now question this deification of scientists and believe Nobel prizes are dangerously out of kilter with the processes of modern research. By stressing individual achievements, they say, Nobels encourage competition at the expense of cooperation. They want the system to be changed.

Because you didn’t build that, after all. Clearly, the entire society should be awarded prizes for contributing. Just as is true with any form of financial capital, so with human. We all contributed, all should gain the baubles. Filtered through the pure and just who are the nomenklatura, obviously.

Costs of Inflation: Financial Intermediation Failure

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 7 Feb 2017In the previous video, we learned that inflation can add noise to price signals resulting in some costly mistakes from price confusion and money illusion. Now, we’ll look at how it can interfere with long-term contracting with financial intermediaries.

Let’s say you want to take out a big loan, such as a mortgage on a house. The financial intermediary (in this case, a commercial bank) is going to charge you an interest rate as their profit for loaning you the money. In this situation, inflation has the potential to work against you or it can work against the bank.

If the bank charges you a nominal interest rate (i.e., the interest rate on paper before taking inflation into account) of 5% and inflation climbs unexpectedly to 10% for the year, the real interest rate (nominal minus inflation) falls to -5%. The bank actually loses money. However, if inflation has been higher and banks are charging 15% for mortgages and inflation rates fall unexpectedly to 3%, you’re stuck paying a real interest rate of 12%!

The above scenarios are similar to what actually happened in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. Inflation was low in the 60s. But then in 70s, inflation rates climbed up unexpectedly. People that purchased a home in the 60s lucked out with low interest rates on their mortgages coupled with higher inflation, and many were able to pay off the loans more quickly than expected. But anyone that purchased a higher interest rate mortgage in the 70s only saw inflation fall back down. It was good for the banks and a costly choice for the homeowners. They were saddled with a high-interest mortgage while lower inflation meant a lower increase in wages.

It’s not that the people buying homes in the 1960s were smarter than those in the 70s. As we’ve noted in previous videos, inflation can be very difficult to predict. When banks expect that inflation might be 10% in the coming years, they will generally adjust their nominal interest rates in order to achieve the desired real interest rate. This relationship between real and nominal interest rates and inflation is known as the Fisher effect, after economist Irving Fisher.

We can see the Fisher effect in the data for nominal interest rates on U.S. mortgages from the 1960s through today. As inflation rates rise, nominal interest rates try to keep up. And as the inflation rates fall, nominal interest rates trail behind.

Now, if inflation rates are both high and volatile, lending and borrowing gets scary for both sides. Long-term contracts like mortgages become more costly for everyone with much higher risk, so it happens less. This is damaging for an economy. Coordinating saving and investment is an important function of the market. If high and volatile inflation is making that inefficient and less common, total wealth declines.

Up next, we’ll explore why governments create inflation in the first place.

QotD: Legal plunder

Sometimes the law defends plunder and participates in it. Thus the beneficiaries are spared the shame and danger that their acts would otherwise involve … But how is this legal plunder to be identified? Quite simply. See if the law takes from some persons what belongs to them and gives it to the other persons to whom it doesn’t belong. See if the law benefits one citizen at the expense of another by doing what the citizen himself cannot do without committing a crime. Then abolish that law without delay — No legal plunder; this is the principle of justice, peace, order, stability, harmony and logic.

Frédéric Bastiat, The Law, 1850.