Sean Gabb makes the case for the least well-known part of the Roman world that outlasted the western empire by a thousand years:

Properly considered, the history of what I will from now call not the Byzantine Empire, but the Mediaeval Roman Empire, is perhaps the most astonishing instance of how courage and determination can keep civilisation alive in the face of the most forbidding and apparently overpowering challenges. In setting out my argument, I hope you will forgive me if I begin with an introduction covering much that many of your will know at least as well as I do, but that may not be so familiar to those reading the text or watching the speech on YouTube.

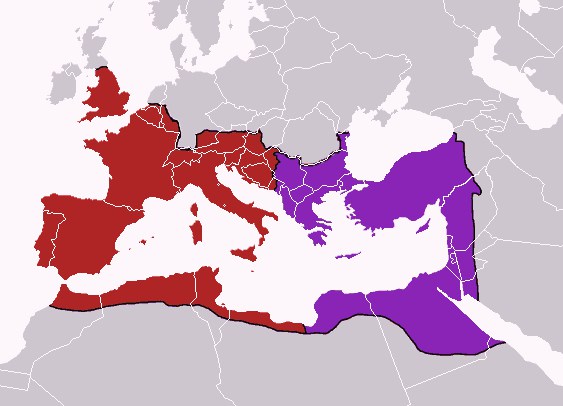

If you look at the first of the maps that I have put on your tables, you will see the Roman Empire as it was in the year 395 AD. This shows the Empire at something close it its greatest extent. The conquests that Trajan made to the north of the Danube and east of the Euphrates have been given up. But it includes the whole of the Mediterranean World and its various hinterlands – an area stretching from the North of England to Upper Egypt, from Casablanca to Trebizond. In that year, however, nearly a century of political experiments is formally ended with the division of the Empire into two administrative zones. There is the Western or the red Empire, ruled by an Emperor in Rome or Milan or Ravenna. There is the Eastern or the purple Empire, ruled by an Emperor in Constantinople.

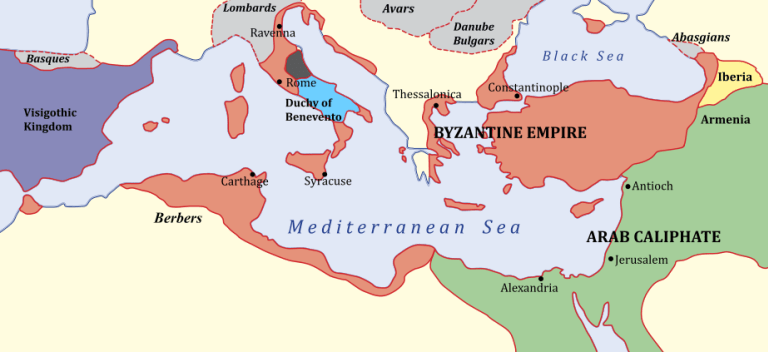

If you look at the second map, dated roughly 650 AD, you will see that the Western Empire has disappeared. Excepting North Africa and parts of Italy, now ruled from Constantinople, the whole of the Western Empire has disappeared – replaced by a set of barbarian kingdoms from which modern Europe takes its origin. The Eastern Empire itself has lost both Syria and Egypt to the Arabs.

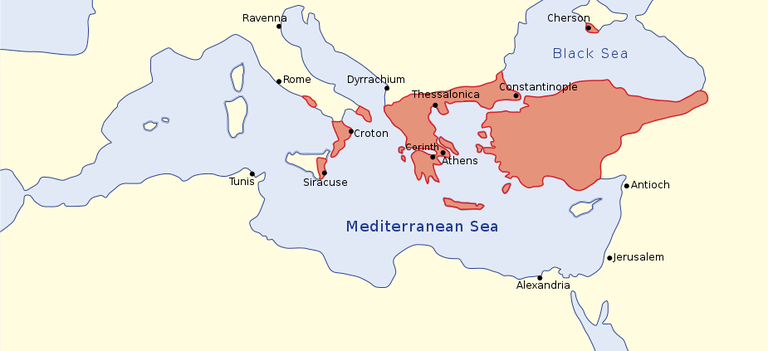

If you look at the third map, dated roughly 867 AD, you will see that the Empire has suffered the further loss of Cyprus and North Africa and most of Sicily. Nevertheless, what we have in that year should undeniably be called the Mediaeval Roman Empire. It has weathered the storm of the Early Middle Ages. It is the richest and most powerful state in the Mediterranean World. Indeed, during the next few centuries, it will expand. It has already reconquered Greece. It will conquer the Bulgarian Kingdom and re-establish its ancient frontier on the Danube. It will even retake Antioch and make Egypt for a while its economic and diplomatic client.

After 1071, the Empire falls on evil days. In that year, the Turks deprive it of its Anatolian heartland. But this loss is stabilised and in part reversed by a skilful handling of the Crusades. There is another disaster in 1204, when the Venetians take and plunder Constantinople. But this is not the end. The Empire is restored in large parts in 1261; and, even if as little more than a city-state based around Constantinople, it continues to the final Turkish conquest of 1453. Indeed, the formal extinction of the Empire comes nearly a decade after 1453, with the annexation of its last territories in Southern Greece.

There was a time when school textbooks in England dated the fall of the Roman Empire to 476 AD. Its continued survival for a thousand years after then had to be explained, where admitted, by taking a contemptuous view of what was called the Byzantine Empire. See, for example, W.E.H. Lecky:

Of that Byzantine empire, the universal verdict of history is that it constitutes, without a single exception, the most thoroughly base and despicable form that civilization has yet assumed. There has been no other enduring civilization so absolutely destitute of all forms and elements of greatness, and none to which the epithet “mean” may be so emphatically applied… The history of the empire is a monotonous story of the intrigues of priests, eunuchs, and women, of poisonings, of conspiracies, of uniform ingratitude.

Lecky is one of my favourite historians. But, if you look even at the mediaeval Greek and Italian historians of the Empire, you will see that this is a bizarre judgement. Undoubtedly, these historians tended to focus on intrigues in and about the Imperial Palace. But they also record much else. They record the story of a rich and powerful empire, directed with high military and diplomatic ability – an empire in which slavery and the death penalty have been almost abolished, where people lived, and knew that they lived, under a set of divinely-ordained laws that protected life, liberty and property to a degree unknown in any other mediaeval state.