Published on 10 Jun 2012

This six-part, three-hour, BBC TV series aired in 1997. I presented and co-wrote the series; it was directed by James Muncie, with music by Brian Eno.

The series was based on my 1994 book, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: What Happens After They’re Built. The book is still selling well and is used as a text in some college courses. Most of the 27 reviews on Amazon treat it as a book about system and software design, which tells me that architects are not as alert as computer people. But I knew that; that’s part of why I wrote the book.

Anybody is welcome to use anything from this series in any way they like. Please don’t bug me with requests for permission. Hack away. Do credit the BBC, who put considerable time and talent into the project.

Historic note: this was one of the first television productions made entirely in digital — shot digital, edited digital. The project wound up with not enough money, so digital was the workaround. The camera was so small that we seldom had to ask permission to shoot; everybody thought we were tourists. No film or sound crew. Everything technical on site was done by editors, writers, directors. That’s why the sound is a little sketchy, but there’s also some direct perception in the filming that is unusual.

September 3, 2015

How Buildings Learn – Stewart Brand – 6 of 6 – “Shearing Layers”

The beer ineQuality index

I took a couple of weeks off over the summer and subsequently forgot some of the interesting articles I’d intended to link to from the blog (but no sensible person comes here for breaking news, do they?). Here’s one from the wonderfully named Worthwhile Canadian Initiative blog:

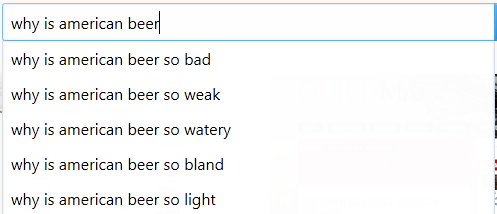

The conventional Canadian view is that American beer is bad; watery and weak. Yet American breweries produce some of the world’s best beers — superb brews coming out of microbreweries across the country.

What is striking about the United States is the country’s level of inequality — or, to be more precise, the beer quality inequality. Countries like Germany, Belgium — the Scandinavian countries in general — have much less variation in the quality of their beer.

The question is: why? Does beer quality inequality result from other forms of inequality, like disparities in income and wealth? Or do the forces that produce income inequality also produce beer quality inequality? Is it a spurious correlation, or is the armchair empiricist’s observation that the US has more beer ine-quality simply wrong?

The income-causes-beer quality inequality story is easily told. Some people are poor. They demand cheap beer, and cheap beer is necessarily poor quality. Some people are rich. They demand high quality beer, and are willing to pay for it. Hence, in theory, we would expect income inequality to produce beer quality inequality. As an empirical observation, the US has substantially more income and beer quality inequality than other rich countries, including Canada, while Scandinavian countries have some of the lowest levels of income and beer inequality in the world (here). So income inequality causes beer quality inequality: Q.E.D.

This story is plausible, and there may be some truth to it. The problem with it is that not everybody drinks beer. Take a country like England, for example. There beer was traditionally a working man’s drink — the upper classes sipped Pimm’s on the lawn, or perhaps a gin and tonic. If the rich aren’t drinking beer, an increased concentration of income in the hands of the richest 1 percent will have no impact on the variation in beer quality.

Neil Peart recants his early Ayn Rand infatuation

Last month, Reason‘s Brian Doherty found four prominent Ayn Rand fans who’ve eventually thrown off the yoke of Objectivism (or Objectivism-fellow-traveller-ism) and now don’t want to be in any way associated with their former guru, including Neil Peart:

Peart, drummer and lyricist for rock band Rush, would clearly rather not be asked about his early-career loud enthusiasm for Rand and her ideas. The well-reviewed 2010 documentary on the band, Beyond the Lighted Stage, mentions her barely at all. (I recall not at all but am using less certain language as I don’t have a full transcript to consult.) Rand’s importance is ignored by the film, though she was central to one of the core conundrums of Rush history: why did rock intellectuals and tastemakers hate on this excellent band so much and for so long?

After years of Peart’s lyrics dissing metaphorical arboreal labor unions, declaring his mind is not for rent to any God or government (Rand’s top two villains), and hat-tipping explicitly in the liner notes to the concept LP 2112 to the “genius of Ayn Rand,” he felt the albatross of 18-minute prog suites and silly ’70s stage garbs was enough for one poor percussionist to bear, and decided to drop the burden of Rand.

Peart most recently tried to distance himself from Randian libertarianism in a Rolling Stone profile of the band, as discussed here by Matt Welch, who quoted the core of Peart’s apostasy:

Rush’s earlier musical take on Rand, 1975’s unimaginatively titled “Anthem,” is more problematic [than 2112], railing against the kind of generosity that Peart now routinely practices: “Begging hands and bleeding hearts will/Only cry out for more.” And “The Trees,” an allegorical power ballad about maples dooming a forest by agitating for “equal rights” with lofty oaks, was strident enough to convince a young Rand Paul that he had finally found a right-wing rock band.

Peart outgrew his Ayn Rand phase years ago, and now describes himself as a “bleeding-heart libertarian,” citing his trips to Africa as transformative. He claims to stand by the message of “The Trees,” but other than that, his bleeding-heart side seems dominant. Peart just became a U.S. citizen, and he is unlikely to vote for Rand Paul, or any Republican. Peart says that it’s “very obvious” that Paul “hates women and brown people” — and Rush sent a cease-and-desist order to get Paul to stop quoting “The Trees” in his speeches.

“For a person of my sensibility, you’re only left with the Democratic party,” says Peart, who also calls George W. Bush “an instrument of evil.” “If you’re a compassionate person at all. The whole health-care thing — denying mercy to suffering people? What? This is Christian?”

“Outgrew” is the closest thing to an explanation, and there is no explanation at all for his reasoning that libertarianoid Rand Paul (whose name is no relation to Ms. Rand’s) is anti-woman and anti-brown people, or what about his “sensibility” matches the Democrats.

Peart clearly vibed with a general anti-authoritarianism he saw in Rand, and with her objection to enforced equality. But a more nuanced attempt to distance himself from Randian libertarianism in an interview Peart did for a feature in the libertarian magazine Liberty in 1997 (by the Institute for Justice’s Scott Bullock) made it clear that Peart’s attraction to Rand was more about her underlying sense of individualism and the nobility of the artist and his intentions than it was about all the complicated policy implications that Rand, and her libertarian fans, drew from her philosophy.

Bullock skillfully teases out the fact that Rand’s morality implied a belief in free markets as well as a general individualist sense of “freedom” seemed to have never quite been embedded in Peart’s DNA. And indeed Fountainhead‘s individualist message is largely that the creative artist can and ought to follow his own whims and spirit no matter what markets do (while never suggesting anyone should be forced to support a great artist, or prevented by force from supporting mediocre ones).

Reparations for India’s colonial period?

In Time, Shikha Dalmia explains why India may not want to cuddle up too closely to the idea of getting reparations from the UK:

Indian politician and celebrated novelist Shashi Tharoor caused a mini-sensation late last month when he went before the Oxford Union, a debating society in England’s prestigious eponymous university, and argued that Britain needed to give India reparations for “depredations” caused by two centuries of colonial rule. It was a virtuoso performance — almost pitch perfect in substance and delivery — that handily won him the debate in England and made him a national hero at home.

But the most eloquent point that emerged in the debate is one he didn’t make: While Brits are grappling with their sordid past by, say, holding such debates, Indians are busy burying theirs in a cheap feel-goodism.

Colonialism, without a doubt, is an awful chapter in human history. And Tharoor did a brilliant job of debunking the standard argument of Raj apologists that British occupation did more good than harm because it gave India democracy and the rule of law. (This is akin to American whites who argued after the Civil War that blacks had nothing to complain about because — as the Chicago Tribune editorialized — in exchange for slavery, they were “taught Christian civilization and to speak the noble English language instead of some African gibberish.”)

[…]

Reparations make sense when it is still possible to identify the individual victims of political or social violence. But if paying collective reparations for collective guilt is appropriate, then how about India “atoning” for thousands of years of its caste system? This system has perpetrated “depredations” arguably worse than those of colonialism or apartheid against India’s dalits — or untouchables — and other lower castes. And despite what Hindu denialists claim, this system remains an endemic part of everyday life in many parts of India. Indeed, much like the Jim Crow south, local village councils even today severely punish inter-caste mingling and marriage, even issuing death sentences against young men and women who dare marry outside their caste.

None of this is meant to single out India. Alexis de Tocqueville, the great French philosopher, who visited America in the early 19th Century, expressed astonishment at how Americans could blithely both claim to love liberty and defend slavery without any sense of contradiction. Every civilization has its stock of virtues and vices, ideals and transgressions. Moral progress requires each to constantly parse its history and present to measure how far it has come and how far it must go to bridge the gap between its principles and practices.

QotD: The lingering malady of poetry

For no man, of course, ever quite gets over poetry. He may seem to have recovered from it, just as he may seem to have recovered from the measles of his school-days, but exact observation teaches us that no such recovery is ever quite perfect; there always remains a scar, a weakness and a memory.

Now, there is reason for maintaining that the taste for poetry, in the process of human development, marks a stage measurably later than the stage of religion. Savages so little cultured that they know no more of poetry than a cow have elaborate and often very ingenious theologies. If this be true, then it follows that the individual, as he rehearses the life of the species, is apt to carry his taste for poetry further along than he carries his religion — that if his development is arrested at any stage before complete intellectual maturity that arrest is far more likely to leave hallucinations.

H.L. Mencken, “The Nature of Faith”, Prejudices, Fourth Series, 1924.