David Hill learns a very hard lesson about trusting English promises:

It was the summer of 1909. I was on the south coast of Spain. I remember it well because the season was almost over. Peace was within reach, I felt. There had been a vote to end the war, and the English had told me to support it. But the vote needed to be unanimous to pass, and it failed. The Russian, the Italian, they thought the English voted against it and that I had been lied to. Why should I believe them? The English and I had worked together against all of them for years now. Of course they’d want to sow distrust between us. Now time was ticking. I desperately wanted peace. I wasn’t sure my country would survive another couple of years, with or without England’s help. There wouldn’t be another vote until after the fall.

“Will you support my army in Spain this fall?” I asked.

“Nah. That ain’t happenin’,” the Englishman replied. A wave of dread came over me. He intended to betray me.

“How could you do this to me? After everything I’ve done for you.”

“I guess I’m just a hard muthafucka like that.”

And with that he walked away, leaving me standing in the hallway, mouth agape. He rejoined the other players at the board, who all stared at me, fury in their eyes. We told you so.

I used to spend a lot of time playing Diplomacy, but as I didn’t have enough real-life friends to want to lose a lot of them over a boardgame, I played postal Diplomacy (I even co-published a ‘zine for a while).

If you’ve ever heard of Diplomacy, chances are you know it as “the game that ruins friendships.” It’s also likely you’ve never finished an entire game. That’s because Diplomacy requires seven players and seven or eight hours to complete. Games played by postal mail, the way most played for the first 30 years of its existence, could take longer than a year to finish. Despite this, Diplomacy is one of the most popular strategic board games in history. Since its invention in 1954 by Harvard grad Allan B. Calhamer, Diplomacy has sold over 300,000 copies and was inducted into Games Magazine’s hall of fame alongside Monopoly, Clue, and Scrabble.

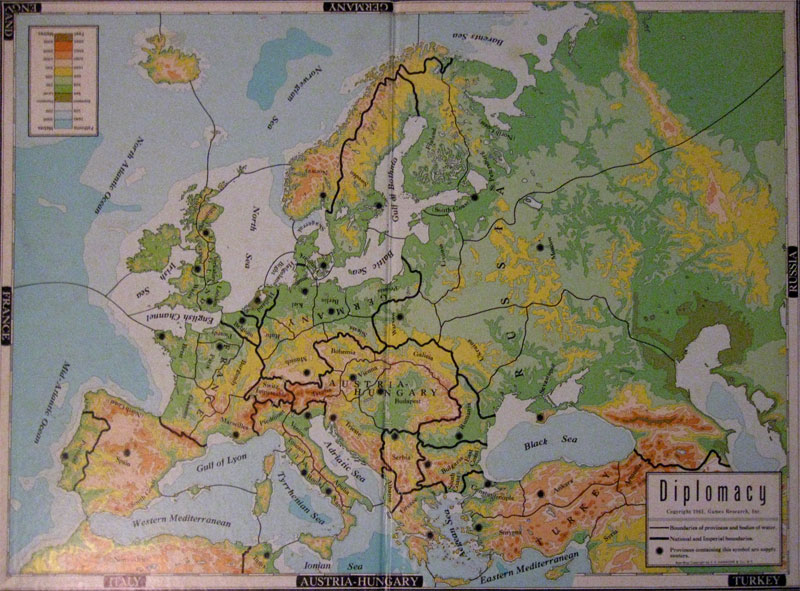

The game is incredibly simple. The game board is a map of 1914 Europe divided into 19 sea regions and 56 land regions, 34 of which contain what are known as “supply centers.” Each player plays as a major power (Austria-Hungary, Turkey, Italy, England, France, Russia, Germany) with three pieces on the board (four for Russia) known as “home supply centers.” Each piece can move one space at a time, and each piece has equal strength. When two pieces try to move to the same space, neither moves. If two pieces move to the same space but one of those pieces has “support” from a third piece, the piece with support will win the standoff and take the space. The goal is to control 18 supply centers, which rarely happens. What’s more common is for two or more players to agree to end the game in a draw. Aside from a few other special situations, that’s pretty much it for rules.

There are two things that make Diplomacy so unique and challenging. The first is that, unlike in most board games, players don’t take turns moving. Everyone writes down their moves and puts them in a box. The moves are then read aloud, every piece on the board moving simultaneously. The second is that prior to each move the players are given time to negotiate with each other, as a group or privately. The result is something like a cross between Risk, poker, and Survivor — with no dice or cards or cameras. There’s no element of luck. The only variable factor in the game is each player’s ability to convince others to do what they want. The core game mechanic, then, is negotiation. This is both what draws and repels people to Diplomacy in equal force; because when it comes to those negotiations, anything goes. And anything usually does.