![]() My weekly Guild Wars 2 community round-up at GuildMag is now online. Living Story Season Two began on Canada Day this week … so my Canadian friends were heavily represented in game right as the new content launched. So far, we’ve only seen a small section of the new region, but it’s been a lot of fun to explore. In addition, there’s the usual assortment of blog posts, videos, podcasts, and fan fiction from around the GW2 community.

My weekly Guild Wars 2 community round-up at GuildMag is now online. Living Story Season Two began on Canada Day this week … so my Canadian friends were heavily represented in game right as the new content launched. So far, we’ve only seen a small section of the new region, but it’s been a lot of fun to explore. In addition, there’s the usual assortment of blog posts, videos, podcasts, and fan fiction from around the GW2 community.

July 4, 2014

This week in Guild Wars 2

The Queen formally names the new aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth

A break with tradition, as the ship was christened with a bottle of Bowmore whisky, rather than a bottle of champagne:

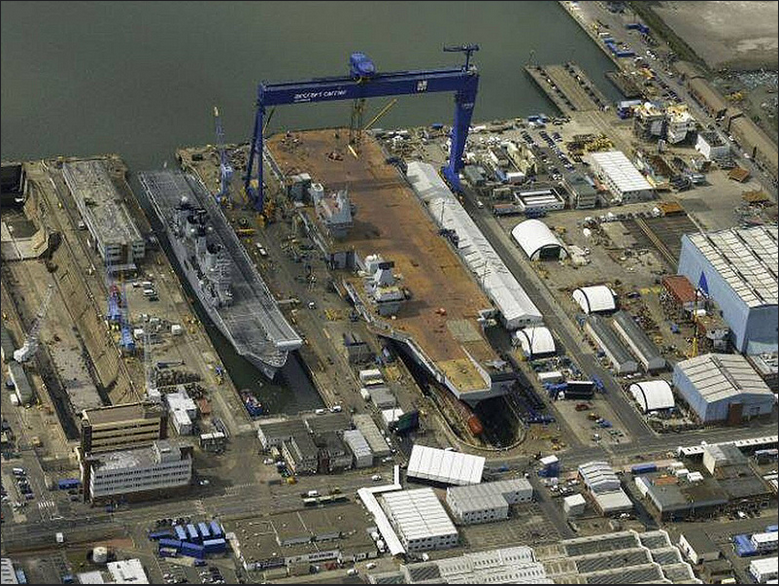

HMS Queen Elizabeth is pictured in Rosyth Dockyard where Queen Elizabeth II will formally name the Royal Navy’s biggest ever ship on July 4, 2014 in Fife, Scotland. With whisky replacing the more traditional champagne at the ceremony, Queen Elizabeth II will smash a bottle of Islay malt whisky against HMS Queen Elizabeth at the event at Rosyth Dockyard, where the 65,000-tonne aircraft carrier has been assembled and fitted out. (Photo by Andrew Milligan – WPA Pool /Getty Images)

A bottle of whisky was smashed on the hull of the 65,000-tonne HMS Queen Elizabeth — the first of two new Royal Navy aircraft carriers being built.

The Red Arrows flew over the dockyard before the ship was officially named.

First Sea Lord Admiral George Zambellas said the ship was “fit for a Queen”.

“HMS Queen Elizabeth will be a national instrument of power and a national symbol of authority,” he said in a speech.

“That means she will be a national icon too, all the while keeping the great in Great Britain and the royal in Royal Navy.”

Addressing the audience, the Queen said the “innovative and first class” warship, the largest ever to be built in the UK, ushered in an “exciting new era”.

“In sponsoring this new aircraft carrier, I believe the Queen Elizabeth will be a source of inspiration and pride for us all,” she said.

“May God bless her and all who sail in her.”

And even the bloody BBC gets it wrong: the ship is named for Queen Elizabeth I, not the current monarch … when the Royal Navy names a ship for a monarch, like the battleship HMS King George V for example, it indicates which King George is being memorialized. HMS Queen Elizabeth is the third time the Royal Navy has named a ship for the Virgin Queen: the first being the lead ship of a class of super-dreadnoughts launched just before the outbreak of WW1, and the second being the lead ship of a class of never-built aircraft carriers in the 1960s (no, I don’t know why that counts: ask the RN about that).

Update 17 July: A few photos from Jeff Head’s Flickr stream show the contrast between the soon-to-be-retired HMS Illustrious and the soon-to-be-launched HMS Queen Elizabeth:

Civilization: Beyond Earth release date announced

ZAM.com has the details:

Civilization: Beyond Earth is set to launch worldwide this autumn on October 24, 2014. Pre-ordering via participating retailers will score you a bonus Exoplanets Map Pack on launch day. The map pack includes six custom maps inspired by real exoplanets:

- Kepler 186f: This lush forest planet is one of the oldest known Earth-like planets

- Rigil Khantoris Bb: Orbiting the closest star to our solar system, the historical records of this arid continental planet’s settlement are well-preserved

- Tau Ceti d: This planet of seas and archipelagos features a booming biodiversity and a wealth of resources

- Mu Arae f: Tidally locked in orbit around a weak star, the southern hemisphere of this planet is a blistering desert where the sun never sets, while the northern hemisphere is perpetually in frozen darkness

- 82 Eridani e: An alien world of scarce water and wracked by tectonic forces

- Eta Vulpeculae b: A mysterious new discovery with unknown terrain

QotD: The English Civil War of 1776

It is fashionable today to view the Revolution as one might a traditional war between foreign powers, but, in truth, the break of 1776 was the latest in a series of fallings out between brothers — a civil war fought by men who were separated by an ocean but not by a history. Reading through the extraordinary profusion of pamphlets and gripes that the crisis produced, one cannot help but be impressed by how keenly the revolutionaries hewed to existing principle. Thomas Paine, perhaps the most radical of the agitators, may have believed that he could start the world all over again, but the colonists who marched with him mostly definitely did not. Instead, they sought a restoration of their inheritance, the Constitutional Congress asserting in 1774 that British subjects in America were “entitled to all the rights, liberties, and immunities of free and natural-born subjects, within the realm of England.” In the same year, William Henry Drayton, a lawyer from South Carolina who later served as a delegate to the Congress, fleshed out the claim, establishing in a tract of his own that he and his countrymen were “entitled to the common law of England formed by their common ancestors; and to all and singular the benefits, rights, liberties and claims specified in Magna Charta, in the petition of Rights, in the Bill of Rights, and in the Act of Settlement.” With this popular sentiment, Drayton and his acolytes set themselves up as the Roundheads of the New World, linking spiritual arms with the parliamentarians of the English civil war, with the seditious architects of the Glorious Revolution, and with all who had established colonial outposts in the name of English freedom.

[…]

Fear of potentates ran deep within the Anglo-American tradition. When the mutinous Immortal Seven ushered in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, their invitation to William of Orange related that the people were “generally dissatisfied with the present conduct of the government, in relation to their religion, liberties and properties (all which have been greatly invaded).” As Daniel Hannan observes in Inventing Freedom, these three objects were philosophically inextricable. Protestantism, Hannan notes, was seen by the architects of English liberty in “political rather than theological terms, as guarantor of free speech, free conscience, and free parliament”; Catholicism, by contrast, was held to consume those virtues and to lead, inexorably, to monarchy. The fear of “popery” that helped to usher in the Glorious Revolution was certainly more pronounced in England that it was in America. But the concerns that motivated it were not, being instead inseparable from the fundamental political question, which was, “are we to rule ourselves or are we to be ruled by Kings and by Popes?” It stood to reason then that those who had become accustomed to expecting to enjoy a relationship with God that was not refereed by a host of spiritual bureaucrats would be able to more easily imagine governing their own worldly affairs, as it made sense that a culture in which the laity was encouraged to read Scripture for itself would be one in which subjects would more quickly rush to the defense of parliaments against the King. As ever, the instinct was toward the fragmentation of power.

Charles C.W. Cooke, “The Civil War of 1776”, National Review, 2014-07-03.