Note the warning at the bottom of the image:

If you’re basing radiation safety procedures on an internet PNG image and things go wrong, you have no one to blame but yourself.

Fuller explanation here.

Note the warning at the bottom of the image:

If you’re basing radiation safety procedures on an internet PNG image and things go wrong, you have no one to blame but yourself.

Fuller explanation here.

In the comments to a post at BoingBoing about something called a shooter’s sandwich (which itself sounds remarkably edible) was a link to Huntsman cheese. I’ve actually had Huntsman cheese, although I didn’t know it had a formal name: it’s Stilton and Double Gloucester cheeses in alternating layers (very tasty).

Having already made myself hungry — I got up late this morning and still haven’t had breakfast — I followed the link for Stilton cheese to discover the following little bit of EU nomenclature inanity:

Stilton is a type of English cheese, known for its characteristic strong smell and taste. It is produced in two varieties: the well-known blue and the lesser-known white. Both have been granted the status of a protected designation of origin by the European Commission, together one of only seventeen British products to have such a designation. Only cheese produced in the three English counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, and Nottinghamshire — and made according to a strict code — may be called “Stilton”. This means that cheese produced in Stilton, the village in Cambridgeshire for which the cheese is named, would not legally be allowed to be called Stilton Cheese.

Absurd, right? Well, for a change, there is actually a good reason for the restriction:

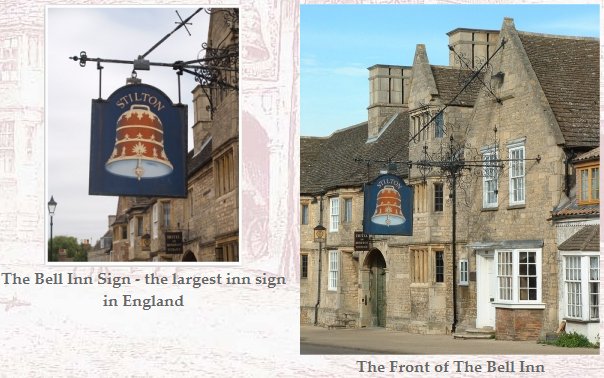

It is commonly believed that the pioneer of blue Stilton was Cooper Thornhill, owner of the Bell Inn on the Great North Road, in the village of Stilton, Huntingdonshire. Traditional legend has it that in 1730, Thornhill discovered a distinctive blue cheese while visiting a small farm near Melton Mowbray in rural Leicestershire — possibly in Wymondham. He fell in love with the cheese and made a business arrangement that granted the Bell Inn exclusive marketing rights to blue Stilton. Soon thereafter, wagon loads of cheese were being delivered to the inn. Since the main stagecoach routes from London to Northern England passed through the village of Stilton he was able to promote the sale of this cheese and the fame of Stilton rapidly spread. However, the first known written reference to Stilton cheese was in William Stukeley’s Itinerarium Curiosum, letter V, dated October 1722, and in his 1724 work A tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain Daniel Defoe describes Stilton cheese as “famous”.

So the cheese called “Stilton” isn’t actually made in Stilton. However, the Bell Inn is still there, and you can indeed get a meal with Stilton cheese in the building that helped to make it famous. I’d dig out my photos of the building, but I was there in the pre-digital photography age, so I’m not at all certain where they are . . .

An interesting legal precedent may not be as far-reaching as the headline might imply:

Breaking in to an encrypted router and using the WiFi connection is not an criminal offence, a Dutch court ruled. WiFi hackers can not be prosecuted for breaching router security.

A court in The Hague ruled earlier this month that it is legal to break WiFi security to use the internet connection. The court also decided that piggybacking on open WiFi networks in bars and hotels can not be prosecuted. In many countries both actions are illegal and often can be fined.

[. . .]

The Judge reasoned that the student didn’t gain access to the computer connected to the router, but only used the routers internet connection. Under Dutch law breaking in to a computer is forbidden.

A computer in The Netherlands is defined as a machine that is used for three things: the storage, processing and transmission of data. A router can therefore not be described as a computer because it is only used to transfer or process data and not for storing bits and bytes. Hacking a device that is no computer by law is not illegal, and can not be prosecuted, the court concluded.

The key here is the definition of a computer under the law: I expect the Dutch to update this definition in response to the outcome of this case.

Powered by WordPress