Philip Klein looks at the faulty notions behind the Obama administration’s push for high speed railways:

To most Americans, the passing reference to California was likely an afterthought, lost amid all the dreamy rhetoric of rebuilding the nation. But upon closer inspection, the state’s proposed high-speed rail system serves as a perfect example of the gap between the promise of transformational liberalism and the reality of big government. Taxpayers everywhere should pay attention, because the project has already been granted $3.2 billion in federal funds, mostly through Obama’s economic stimulus package — and its backers hope to gobble up billions more over the next decade.

The $43 billion transportation project to link Los Angeles to San Francisco with a bullet train by 2020 would be considered grandiose during the plushest of times, yet it’s being pursued during an era when governments at all levels are mired in deep fiscal crises. The plan has been subject to a series of scathing reports by independent analysts, raising concerns about everything from its cost estimates to its business model. The University of California at Berkeley has questioned its lofty ridership projections. And even the Washington Post has editorialized against it.

It’s a huge wodge of cash from a government that’s already struggling with record deficits, handed to state governments who are in many cases even worse off financially, yet must match the federal funds or lose the subsidy.

Calling it a “system” is misleading, as none of the currently imagined lines would inter-connect. Nobody seems to be worried that there will not be enough passenger traffic to justify the enormous acquisition, construction, and operational costs for these train services.

“The cost projections are overly optimistic,” Wendell Cox, a public policy consultant and co-author of a critical report for the libertarian Reason Foundation, says. “The ridership projections are absolutely crazy. The thing will have no impact on highway traffic and will have little or no impact on the amount of planes in the air. This project really defines the term ‘boondoggle.'”

[. . .]

BRINGING HIGH-SPEED RAIL to America has been a decades-long dream for liberals, who have long envied Europe’s extensive rail system. Building a high-speed rail network, they hope, would move the nation away from automobiles and reduce pollution. It has the added bonus of being a massive, centrally planned public works project. The problem is just because rail has worked elsewhere, that doesn’t mean it makes sense here.

“We’re not like Spain or France, where the population densities are a lot higher, and the cities are not as spread out,” Ken Orski, a former transportation official in the Nixon and Ford administrations and publisher of the newsletter Innovation Briefs, says. “So you can connect cities like Barcelona and Madrid or Paris and Marseilles easily.”

The best place to build a high speed rail system for the US would be the Boston-New York-Washington corridor (aka “Bosnywash”, for the assumed urban agglomeration that would occur as the cities reach toward one another). It has the necessary population density to potentially turn an HSR system into a practical, possibly even profitable, part of the transportation solution. The problem is that without an enormous eminent domain land-grab to cheat every land-owner of the fair value of their property, it just can’t be done. Buying enough contiguous sections of land to connect these cities would be so expensive that scrapping and replacing the entire navy every year would be a bargain in comparison.

The American railway system is built around freight: passenger traffic is a tiny sliver of the whole picture. Ordinary passenger trains cause traffic and scheduling difficulties because they travel at higher speeds, but require more frequent stops than freight trains, and their schedules have to be adjusted to passenger needs (passenger traffic peaks early to mid-morning and early to mid-evening). The frequency of passenger trains can “crowd out” the freight traffic the railway actually earns money on.

Most railway companies prefer to avoid having the complications of carrying passengers at all — that’s why Amtrak (and VIA Rail in Canada) was set up in the first place, to take the burden of money-losing passenger services off the shoulders of deeply indebted railways. Even after the new entity lopped off huge numbers of passenger trains from its schedule, it couldn’t turn a profit on the scaled-down services it was offering.

Ordinary passenger trains can, at a stretch, share rail with freight traffic, but high speed trains cannot. At higher speeds, the actual construction of the track has to change to deal with the physical problem of safely guiding the fast passenger trains along the rail. Signalling must also change to suit the far-higher speeds — and the matching far-longer safe braking distances. High speed rail lines cannot be interrupted with grade crossings, for the safety of passengers and bystanders, so additional bridges and tunnels must be built to avoid bringing road vehicles and pedestrians too close to the trains.

In other words, a high speed railway line is far from being just a faster version of what we already have: it would have to be built separately, to much higher standards of construction.

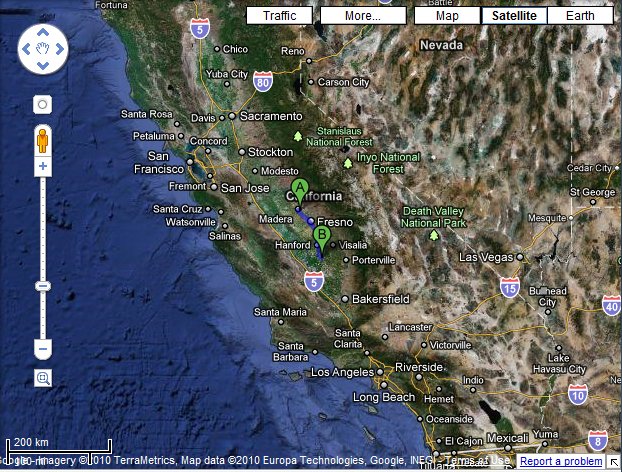

Getting back to the California HSR line; it goes from A to B on this map:

Okay, you think, at least Fresno will get some snazzy slick rail service . . . except this section will be built but not operated until further connecting sections are built . . . at a later date. Maybe. It will be the track, including elevated sections through Fresno, and the physical right-of-way, but no electrical system to power the trains; but that’s fine, because the budget doesn’t include any actual trains.

Of course, this is an old hobby horse of mine and I’ve posted about High Speed Railways a few times before.

The 2012 London Olympics are more than a year away, but Iran already is threatening to boycott them. According to Bahram Afsharzadeh, secretary general of Iran’s National Olympic Committee, the 2012 Olympic logo secretly spells out the word “Zion,” which makes it “racist.” The Iranians also claim that use of the logo “is a disgracing action and against the Olympics’ valuable mottos.”

The 2012 London Olympics are more than a year away, but Iran already is threatening to boycott them. According to Bahram Afsharzadeh, secretary general of Iran’s National Olympic Committee, the 2012 Olympic logo secretly spells out the word “Zion,” which makes it “racist.” The Iranians also claim that use of the logo “is a disgracing action and against the Olympics’ valuable mottos.”