World War Two

Published 1 Jan 2023This war is massive. Our chronological coverage helps give us an understanding of it, but sometimes statistics help us understand the bigger picture.

(more…)

January 3, 2023

1943 in Numbers – WW2 Special

December 29, 2022

Selection bias in polling

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander points out that it’s impossible to do any kind of poll without some selection bias, so you can’t automatically dismiss any given poll on that basis. The kind of selection bias, however, may indicate whether the results will have any relationship to reality:

The real studies by professional scientists usually use Psych 101 students at the professional scientists’ university. Or sometimes they will put up a flyer on a bulletin board in town, saying “Earn $10 By Participating In A Study!” in which case their population will be selected for people who want $10 (poor people, bored people, etc). Sometimes the scientists will get really into cross-cultural research, and retest their hypothesis on various primitive tribes — in which case their population will be selected for the primitive tribes that don’t murder scientists who try to study them. As far as I know, nobody in history has ever done a psychology study on a truly representative sample of the world population.

This is fine. Why?

Selection bias is disastrous if you’re trying to do something like a poll or census. That is, if you want to know “What percent of Americans own smartphones?” then any selection at all limits your result. The percent of Psych 101 undergrads who own smartphones is different from the percent of poor people who want $10 who own smartphones, and both are different from the percent of Americans who own smartphones. The same is potentially true about “how many people oppose abortion?” or “what percent of people are color blind?” or anything else trying to find out how common something is in the population. The only good ways to do this are a) use a giant government dataset that literally includes everyone, b) hire a polling company like Gallup which has tried really hard to get a panel that includes the exact right number of Hispanic people and elderly people and homeless people and every other demographic, c) do a lot of statistical adjustments and pray.

Selection bias is fine-ish if you’re trying to do something like test a correlation. Does eating bananas make people smarter because something something potassium? Get a bunch of Psych 101 undergrads, test their IQs, and ask them how many bananas they eat per day (obviously there are many other problems with this study, like establishing causation — let’s ignore those for now). If you find that people who eat more bananas have higher IQ, then fine, that’s a finding. If you’re right about the mechanism (something something potassium), then probably it should generalize to groups other than Psych 101 undergrads. It might not! But it’s okay to publish a paper saying “Study Finds Eating Bananas Raises IQ” with a little asterisk at the bottom saying “like every study ever done, we only tested this in a specific population rather than everyone in the world, and for all we know maybe it isn’t true in other populations, whatever.” If there’s some reason why Psych 101 undergrads are a particularly bad population to test this in, and any other population is better, then you should use a different population. Otherwise, choose your poison.

December 9, 2022

QotD: Computer models of “the future”

The problem with all “models of the world”, as the video puts it, is that they ignore two vitally important factors. First, models can only go so deep in terms of the scale of analysis to attempt. You can always add layers — and it is never clear when a layer that is completely unseen at one scale becomes vitally important at another. Predicting higher-order effects from lower scales is often impossible, and it is rarely clear when one can be discarded for another.

Second, the video ignores the fact that human behavior changes in response to circumstance, sometimes in radically unpredictable ways. I might predict that we will hit peak oil (or be extremely wealthy) if I extrapolate various trends. However, as oil becomes scarce, people discover new ways to obtain it or do without it. As people become wealthier, they become less interested in the pursuit of wealth and therefore become poorer. Both of those scenarios, however, assume that humanity will adopt a moral and optimistic stance. If humans become decadent and pessimistic, they might just start wars and end up feeding off the scraps.

So, interestingly, what the future looks like might be as much a function of the music we listen to, the books we read, and the movies we watch when we are young as of the resources that are available.

Note that the solution they propose to our problems is internationalization. The problem with internationalizing everything is that people have no one to appeal to. We are governed by a number of international laws, but when was the last time you voted in an international election? How do you effect change when international policies are not working out correctly? Who do you appeal to?

The importance of nationalism is that there are well-known and generally-accepted procedures for addressing grievances with the ruling class. These international clubs are generally impervious to the appeals (and common sense) of ordinary people and tend to promote virtue-signaling among the wealthy class over actual virtue or solutions to problems.

Jonathan Bartlett, quoted in “1973 Computer Program: The World Will End In 2040”, Mind Matters News, 2019-05-31.

October 28, 2022

QotD: “Cliodynamics”, aka “megahistory”

For this week’s musing, I want to discuss in a fairly brief way, my views of “megahistory” or “cliodynamics” – questions about which tend to come up a fair bit in the comments – and also Isaac Asimov, after a fashion. Fundamentally, the promise of these sorts of approaches is to apply the same kind of mathematical modeling in use in many of the STEM fields to history with the promise of uncovering clear rules or “laws” in the noise of history. It is no accident that the fellow who coined the term “cliodynamics”, Peter Turchin, has his training not in history or political science but in zoology; he is trying to apply the sort of population modeling methods he pioneered on Mexican Bean Beetles to human populations. One could also put Steven Pinker, trained as a psychologist, and his Better Angels in this category as well and long time readers will know how frequently I recommend that folks read Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization instead of The Better Angels of our Nature.1

Attentive readers will have already sensed that I have issues with these kinds of arguments; indeed, for all of my occasional frustrations with political science literature (much of which is perfectly fine, but it seems a frequent and honestly overall positive dynamic that historians tend to be highly critical of political scientists) I consider “cliodynamics” to generally take the worst parts of data-driven political science methodologies to apotheosis while discarding most of the virtues of data-driven poli-sci work.

As would any good historian, I have a host of nitpicks, but my objection to the idea of “cliodynamics” has to do with the way that it proposes to tear away the context of the historical data. I think it is worth noting at the outset the claim actually being made here because there is often a bit of motte-and-bailey that goes on, where these sorts of megahistories make extremely confident and very expansive claims and then when challenged is to retreat back to much more restricted claims but Turchin in particular is explicit in Secular Cycles (2009) that “a basic premise of our study is that historical societies can be studied with the same methods physicists and biologists used to study natural systems” in the pursuit of discovering “general laws” of history.

Fundamentally, the approach is set on the premise that the solution to the fact that the details of society are both so complex (imagine charting out the daily schedules of every person one earth for even a single day) and typically so poorly attested is to aggregate all of that data to generate general rules which could cover any population over a long enough period. To my mind, there are two major problems here: predictability and evidence. Let’s start with predictability.

And that’s where we get to Isaac Asimov, because this is essentially also how the “psychohistory” of the Foundation series functions (or, for the Star Trek fans, how the predictions in the DS9 episode “Statistical Probabilities“, itself an homage to the Foundation series, function). The explicit analogy offered is that of the laws that govern gasses: while no particular molecule of a gas can modeled with precision, the entire body of gas can be modeled accurately. Statistical probability over a sufficiently large sample means that the individual behaviors of the individual gas molecules combine in the aggregate to form a predictable whole; the randomness of each molecule “comes out in the wash” when combined with the randomness of the rest.2

I should note that Turchin rejects comparisons to Asimov’s psychohistory (but also embraced the comparison back in 2013), but they are broadly embraced by his boosters. Moreover, Turchin’s claim at the end of that blog post that “prediction is overrated” is honestly a bit bizarre given how quick he is when talking with journalists to use his models to make predictions; Turchin has expressed some frustration with the tone of Graeme Wood’s piece on him, but “We are almost guaranteed” is a direct quote that hasn’t yet been removed and I can speak from experience: The Atlantic‘s fact-checking on such things is very vigorous. So I am going to assume those words escaped the barrier of his teeth and also I am going to suggest here that “We are almost guaranteed” is, in fact, a prediction and a fairly confident one at that.

The problem with applying something like the ideal gas law – or something like the population dynamics of beetles – to human societies is fundamentally interchangeability. Statistical models like these have to treat individual components (beetles, molecules) the way economists treat commodities: part of a larger group where the group has qualities, but the individuals merely function to increase the group size by 1. Raw metals are a classic example of a commodity used this way: add one ton of copper to five hundred tons of copper and you have 501 tons of copper; all of the copper is functionally interchangeable. But of course any economist worth their pencil-lead will be quick to remind you that not all goods are commodities. One unit of “car” is not the same as the next. We can go further, one unit of “Honda Civic” is not the same as the next. Heck, one unit of 2012 Silver Honda Civic LX with 83,513 miles driven on it is not the same as the next even if they are located in the same town and owned by the same person; they may well have wildly different maintenance and accident histories, for instance, which will impact performance and reliability.

Humans have this Honda Civic problem (that is, they are not commodities) but massively more so. Now of course these theories do not formally posit that all, say, human elites are the same, merely that the differences between humans of a given grouping (social status, ethnic group, what have you) “come out in the wash” at large scales with long time horizons. Except of course they don’t and it isn’t even terribly hard to think of good examples.

1 Yes, I am aware that Gat was consulted for Better Angels and blurbed the book. This doesn’t change my opinion of the two books. my issue is fundamentally evidentiary: War is built on concrete, while Better Angels is built on sand when it comes to the data they propose to use. As we’ll see, that’s a frequent issue.

2 Of course the predictions in the Foundation series are not quite flawlessly perfect. They fail in two cases I can think of: the emergence of a singular exceptional individual with psychic powers (the Mule) and situations in which the subjects of the predictions become aware of them. That said Seldon is able to predict things with preposterous accuracy, such that he is able to set up a series of obstacles for a society he knows they will overcome. The main problem is that these challenges frequently involve conflict or competition with other humans; Seldon is at leisure to assume such conflicts are predictable, which is to say they lack Clausewitzian (drink!) friction. But all conflicts have friction; competition between peers is always unpredictable.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: October 15, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-15.

October 27, 2022

QotD: Life expectancy before the modern age

Locke held the same assumptions about life, because life was almost inconceivably cheap in his day. Locke was born in 1632. A person born then would have a decent shot at making it to age 50 if he survived until age 5 … but only about half did. And “a decent shot” needs to be understood blackjack-style. Conventional wisdom says to hit if the dealer shows 16 and you’re holding 16 yourself — even though you’ve got a 62% chance of going bust, you’re all but certain to lose money if you stand. Living to what we Postmoderns call “middle age” was, in Locke’s world, hitting on a 16. We Postmoderns hear of a guy who dies at 50 and we assume he did it to himself — he was a grossly obese smoker with a drug problem or a race car driver or something. In Locke’s world, they’d wonder what his secret was to have made it so long.

Severian, “Overturning Locke: Life”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-09-11.

September 22, 2022

California’s Central Valley of despair

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander wonders why California’s Central Valley is in such terrible shape — far worse than you’d expect even if the rest of California is looking a bit curdled:

Here’s a topographic map of California (source):

You might notice it has a big valley in the center. This is called “The Central Valley”. Sometimes it also gets called the San Joaquin Valley in the south, or the the Sacramento Valley in the north.

The Central Valley is mostly farms — a little piece of the Midwest in the middle of California. If the Midwest is flyover country, the Central Valley is drive-through country, with most Californians experiencing it only on their way between LA and SF.

Most, myself included, drive through as fast as possible. With a few provisional exceptions — Sacramento, Davis, some areas further north — the Central Valley is terrible. It’s not just the temperatures, which can reach 110°F (43°C) in the summer. Or the air pollution, which by all accounts is at crisis level. Or the smell, which I assume is fertilizer or cattle-related. It’s the cities and people and the whole situation. A short drive through is enough to notice poverty, decay, and homeless camps worse even than the rest of California.

But I didn’t realize how bad it was until reading this piece on the San Joaquin River. It claims that if the Central Valley were its own state, it would be the poorest in America, even worse than Mississippi.

This was kind of shocking. I always think of Mississippi as bad because of a history of racial violence, racial segregation, and getting burned down during the Civil War. But the Central Valley has none of those things, plus it has extremely fertile farmland, plus it’s in one of the richest states of the country and should at least get good subsidies and infrastructure. How did it get so bad?

First of all, is this claim true?

I can’t find official per capita income statistics for the Central Valley, separate from the rest of California, but you can find all the individual counties here. When you look at the ones in the Central Valley, you get a median per capita income of $21,729 (this is binned by counties, which might confuse things, but by good luck there are as many people in counties above the median-income county as below it, so probably not by very much). This is indeed lower than Mississippi’s per capita income of $25,444, although if you look by household or family income, the Central Valley does better again.

Of large Central Valley cities, Sacramento has a median income of $33,565 (but it’s the state capital, which inflates it with politicians and lobbyists), Fresno of $25,738, and Bakersfield of $30,144. Compare to Mississippi, where the state capital of Jackson has $23,714, and numbers 2 and 3 cities Gulfport and Southhaven have $25,074 and $34,237. Overall Missisippi comes out worse here, and none of these seem horrible compared to eg Phoenix with $31,821. Given these numbers (from Google), urban salaries in the Central Valley don’t seem so bad. But when instead I look directly at this list of 280 US metropolitan areas by per capita income, numbers are much lower. Bakersfield at $15,760 is 260th/280, Fresno is 267th, and only Sacramento does okay at 22nd. Mississippi cities come in at 146, 202, and 251. Maybe the difference is because Google’s data is city proper and the list is metro area?

Still, it seems fair to say that the Central Valley is at least somewhat in the same league as Mississippi, even though exactly who outscores whom is inconsistent.

September 4, 2022

Who was reading during Plague Year Two, and what format did they prefer?

In the latest edition of the SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte summarizes some of the findings of the most recent Booknet survey:

H/T to Marc Adkins who shared this meme at the perfect moment for me to steal it, file off the serial number and repost it here.

A few months ago, BookNet Canada, which does a lot of valuable research into the book market, released the 2021 edition of its annual survey of Canadian leisure and reading habits. It’s always an interesting study. I was slow getting to it this year because there’s been so much else going on. Here are the ten most interesting findings.

- Canadians have had plenty of time on their hands: 81 per cent report having enough or more than enough leisure. Pre-COVID, about 25 per cent of respondents said they had more-than-enough; during COVID, that jumped to about 35 per cent. The pandemic wasn’t all bad.

- Canadians read books more than they listen to radio or play video games but less than they shop or cook; 42 per cent of us (led by 58 per cent of the 65-plus crowd) read books daily; 35 per cent of the 18-29 age group read daily and 57 per cent of that cohort read at least once a week. Young people are no more likely to read books less than once a month than any other under-65 segment, which bodes well for the future of the industry.

- The statement “books are for enjoyment, entertainment, or leisure” received a ‘yes’ from 62 per cent of respondents, and a ‘sometimes’ from 34 per cent; the statement “books are for learning or education” received a ‘yes’ from 41 per cent of respondents and a ‘sometimes’ from 50 per cent.

- The top reasons for selecting a book to read are the author (40 per cent), the book’s description (30 per cent), recommendations (25 per cent), the main character or the series (20 per cent), its bestselling status (14 per cent), and reference needs (13 per cent). “Recommendations and the impact of bestseller lists have trended down from 2019 to 2021.”

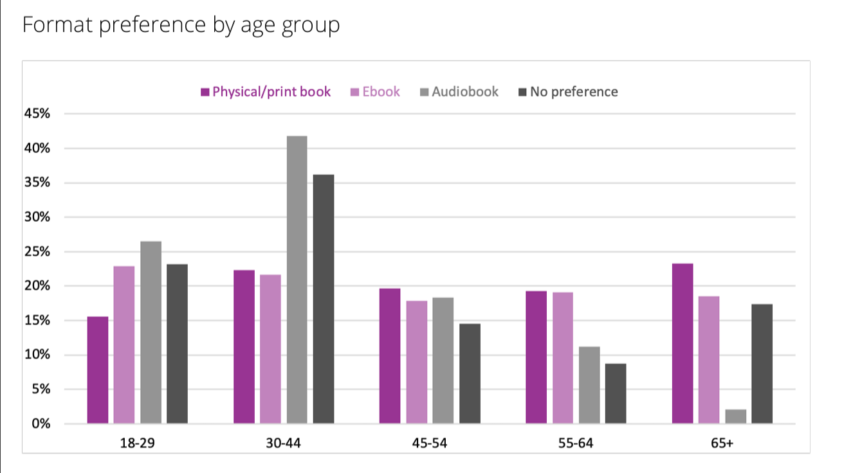

- The love affair with print continues with 68 per cent of readers citing hard copies as their preferred format. Ebooks came in at 16 per cent and audiobooks at 10 per cent Interestingly, readers had a marked preference for paperbacks over hardcovers. Format preferences differ from age group to age group, with some evidence that the kids might not be keen on physical books:

I was interested in that apparent rejection of physical books by the 18-29 cohort so I looked back at the last two years of the survey […] The results are quite different, suggesting a methodological shortcoming (the survey sample is 1,282 adults so the margin of error will be large when you eliminate those who don’t read a given format, those without format preferences, and break the remainder down into five age groups).

August 26, 2022

QotD: The WARG rating – “Wins Above Replacement Goldstein”

No totalitarian regime has ever successfully solved what you might call the Emmanuel Goldstein Problem. They just can’t exist without some kind of existential threat to rally around; it’s their nature. In 1984, the Party simply created Goldstein out of whole cloth, but they seemed to believe this was just another temporary expedient — they were counting on technology to do all the heavy lifting of mass mind control, so they wouldn’t have to resort to things like Goldstein and MiniTrue.

Obviously that ain’t gonna work in Clown World, Cthulhuvious and Sasqueetchia being notso hotso on the STEM. They’ll always need a Goldstein, then, and that’s a real problem, because whatever else Bad Orange Man is, he’s also pushing 80 years old. How long would he have, even in a sane world? 10 more years, tops? And the candidates for Replacement BOM are generally a sorry lot … but even if they weren’t, they’re about to get purged, too. The WARG is already going negative …

For overseas readers (and those not conversant with “Moneyball”: Baseball has these weird “sabermetric” stats that purport to compare players from different teams and eras in terms of absolute value. It’s acronymed (it’s a word) WAR, Wins Above Replacement; “replacement” being an absolutely average player. Like all baseball “sabermetrics” it quickly gets ridiculous, but see here. According to this guy, then, Babe Ruth has a per-season WAR of 10.48 in right field. That means Babe Ruth, himself, personally, alone, was worth 10 and a half wins above your “average” player. If Ruth goes down for the season in a tragic Spring Training beer mishap, you can go ahead and take 10 wins off the Yankees’ record that season (assuming they replace the Bambino with some scrub just off the bus, which back then is what would’ve happened).

WARG, then, is Wins Above Replacement Goldstein. I’d say that Orange Man set the bar for Goldsteins, but that’s not statistically useful, since Trump Derangement Syndrome is so far the apex of liberal lunacy. To make statistical comparisons useful — to find a “replacement Goldstein,” as it were — we have to have someone the Left considered an existential enemy at the time, but who didn’t really do much in the grand scheme of things. So I nominate George W. Bush. If Bush is the “Replacement Goldstein,” then his WARG is a nice round zero. Trump would have a Babe Ruth-ian WARG.

This gives us a convenient measurement for looking at various Republicans, both current and historical. Richard Nixon would have a pretty high WARG — he drove them even more nuts than W. did — and Ronnie Raygun would be up there, too. Gerald Ford would have a slightly negative WARG, since not even the New York Times could pretend Gerald fucking Ford was a threat to the Progressive takeover. Your steeply negative WARGs would be those “Republicans” actively working with the opposition, like Bitch McConnell.

I’d argue that Ron DeSantis and maybe Greg Abbott still have positive WARGs … for now. But they’re going to get gulaged here in pretty short order. Who’s the next guy on the bench? Your Marjorie Taylor Greenes and whatnot drive certain segments of the Left insane, but she’s just too ludicrous to have a positive WARG. And then things start getting really pathetic …

The Law of Diminishing Returns makes the WARG problem even more acute. Freakout fatigue is a real thing. The Media will give it the old college try, of course, but you really just can’t convince people that a goof like Greene is some kind of existential threat to Our Democracy. Her WARG goes negative every time she opens her mouth.

Severian, “Salon Roundup”, Founding Questions, 2022-08-20.

July 29, 2022

“Shrinkflation” isn’t the only way companies try to sell you less for the same price

And, as Virginia Postrel points out, “shrinkflation” does get noticed for economic statistics, unlike some of the other changes many companies are making:

My latest Bloomberg Opinion column is explained well in an excellent subhead (contrary to popular assumptions, writers don’t craft the headlines or subheads that appear on their work): “Packaging less stuff for the same price doesn’t fool consumers or economists. But diminishing quality imposes equally maddening extra costs that are almost impossible to measure.” Excerpt:

If a 16-ounce box contracts to 14 ounces and the price stays the same, I asked Bureau of Labor Statistics economist Jonathan Church, how is that recorded? “Price increase”, he said quickly. You just divide the price by 14 instead of 16 and get the price per ounce. Correcting for shrinkflation is straightforward.

New service charges for things that used to be included in the price, from rice at a Thai restaurant to delivery of topsoil, also rarely sneak past the inflation tallies any more than they fool consumers.

But a stealthier shrinkflation is plaguing today’s economy: declines in quality rather than quantity. Often intangible, the lost value is difficult to capture in price indexes.

Faced with labor shortages, for example, many hotels have eliminated daily housekeeping. For the same room price, guests get less service. It’s not conceptually different from shrinking a bag of potato chips. But would the consumer price index pick up the change?

Probably not, Church said.

This phenomenon, which Doug Johnson aptly dubbed “disqualiflation” in a Facebook comment, is widespread. One example is the four-hour airport security line I chronicled in an earlier Substack post. Another is the barely trained newbie who screws up your sandwich order — a far more common experience today than four years ago. It’s the flip side of a phenomenon I wrote about in The Substance of Style and in economics columns in the early 2000s (see here and here).

During the 2000s and 2010s, inflation was probably overstated because of unmeasured quality increases. Now there’s the opposite phenomenon. Quality reductions have become so pervasive that even today’s scary inflation numbers are almost certainly understated.

If you can read the column at Bloomberg, please do. But if you run into the paywall, which allows a few articles a month, you can use this link to the WaPo version, which doesn’t have links.

June 30, 2022

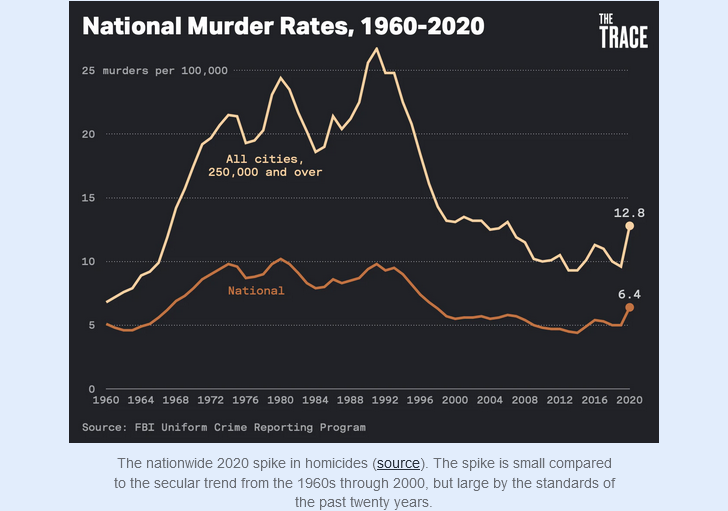

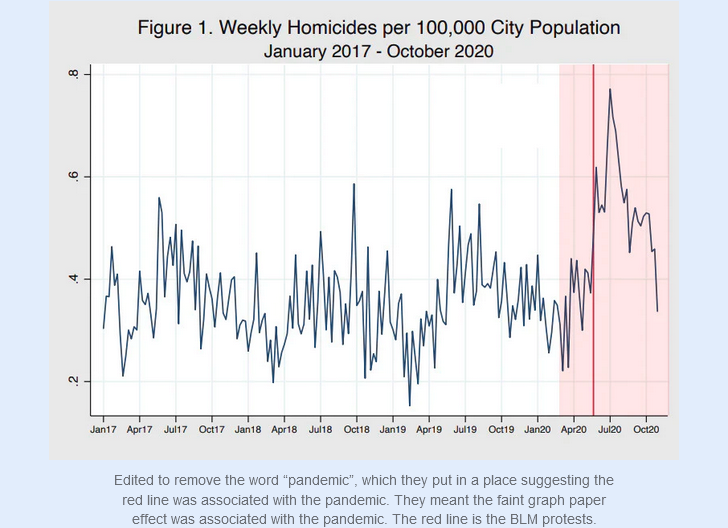

2020’s spike in homicides in the United States

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander looks at the rapid rise in murders across the United States in early 2020, and considers the common explanation for the phenomenon:

In my review of San Fransicko, I mentioned that it was hard to separate the effect of San Francisco’s local policies from the general 2020 spike in homicides, which I attributed to the Black Lives Matter protests and subsequent police pullback.

Several people in the comments questioned my attribution, saying that they’d read news articles saying the homicide spike was because of the pandemic, or that nobody knew what was causing the spike. I agree there are many articles like that, but I disagree with them. Here’s why:

Timing

When exactly did the spike start? The nation shut down for the pandemic in mid-March 2020, but the BLM protests didn’t start until after George Floyd’s death in late May 2020. So did the homicide spike start in March, or May?

Let’s check in with the Council on Criminal Justice:

It very clearly started in late May, not mid-March. The months of March, April, and early May had the same number of homicides as usual.

[…]

Police Pullback

My specific claim is that the protests caused police to do less policing in predominantly black areas. This could be because of any of:

- Police interpreted the protests as a demand for less policing, and complied.

- Police felt angry and disrespected after the protests, and decided to police less in order to show everybody how much they needed them.

- Police worried they would be punished so severely for any fatal mistake that they made during policing that they were less willing to take the risk.

- The “Defund The Police” movement actually resulted in police being defunded, either of literal funds or political capital, and that made it harder for them to police.

I don’t want to speculate on which of these factors was most decisive, only to say that at least one of them must be true, and that police did in fact pull back.

[…]

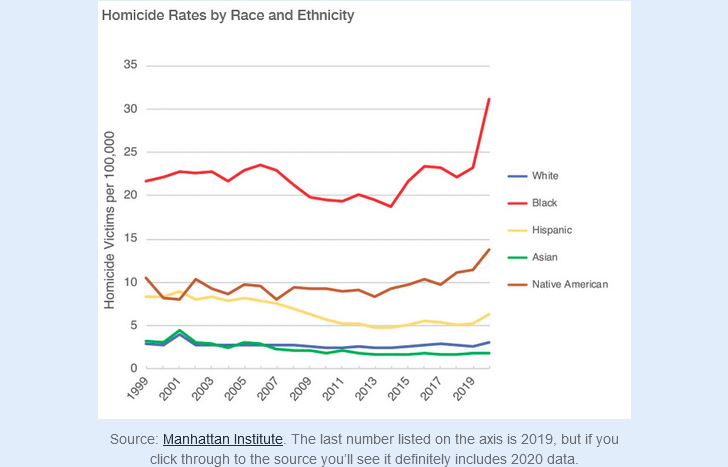

Victims

Who is being targeted in these extra murders?

The 2020 homicide spike primarily targeted blacks.

(there also seems to be a much smaller spike for Native Americans, but there are so few Natives that I think this might be random, or unrelated).

Most violent crime is within a racial community, and there was no corresponding rise in hate crimes the way I would expect if this was whites targeting blacks, so I think the perpetrators were most likely also black. This was a rise in the level of violence within black communities.

A priori there’s no reason to expect lockdowns and “cabin fever” to hit blacks much harder than every other ethnic group. But there are lots of reasons to expect that the Black Lives Matter protests would cause police to pull back from black communities in particular. I think this is independent evidence that the homicide spike was because of the protests and not the pandemic.

June 14, 2022

The Early Roman Emperors – Part 2: An Empire of Peoples

seangabb

Published 4 Oct 2021The Roman Empire was the last and the greatest of the ancient empires. It is the origin from which springs the history of Western Europe and those nations that descend from the Western Roman Empire. It is the political entity within which the Christian faith was born, and the growth of the Church within the Empire, and its eventual establishment as the sole faith of the Empire, have left an indelible impression on all modern denominations. Its history, together with that of the ancient Greeks and the Jews, is our history. To understand how the Empire emerged from a great though finally dysfunctional republic, and how it was consolidated by its early rulers, is partly how we understand ourselves.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the achievement of the early Emperors. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

More by Sean Gabb on the Ancient World: https://www.classicstuition.co.uk/

Learn Latin or Greek or both with him: https://www.udemy.com/user/sean-gabb/

His historical novels (under the pen name “Richard Blake”): https://www.amazon.co.uk/Richard-Blake/e/B005I2B5PO

May 1, 2022

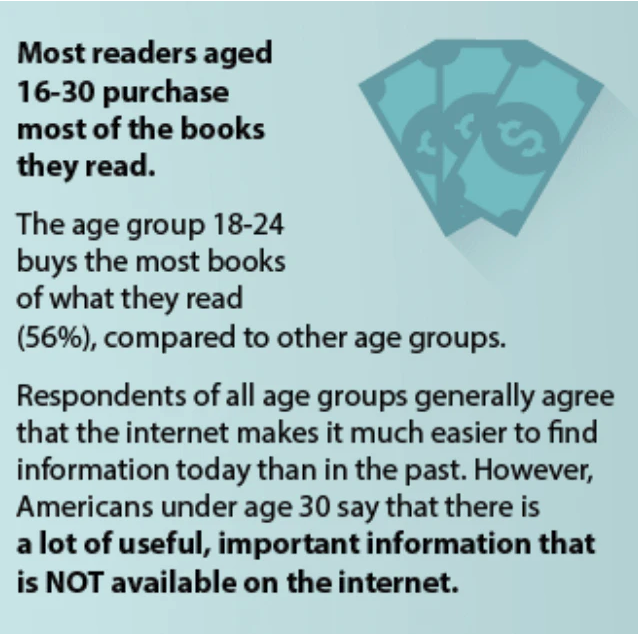

Despite the ever-present smartphone, people are still reading actual books in pretty good numbers

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte provides some mildly hopeful numbers for both readers and writers:

I was having coffee this week with a former star journalist who now (like so many) works in a journalist-adjacent industry. “Who reads books?” she wondered.

It’s a question I’m often asked by journalists who these days get a lot of their information from Twitter. The chore of keeping up with their feed leaves little time for anything else. My guest still read books and belongs to a book club, but she asked the question all the same.

According to the authorities at the PEW Institute, 77% of Americans read books in 2021 (or, to be more precise, read one or more books in one or more format—print, audiobook, ebook). That’s not bad considering only 86% of American adults can read.

Only 21% of women read no books, and 26% of men. Eighty per cent of white people read books (as compared to 62% of Hispanics).

Good news for the future of book reading: 81% of adults under the age of fifty read books compared to 72% of adults over the age of fifty.

More on the demographics: 69% of those earning less than $30,000 a year read books, while 85% of those earning over $75,000 read books; 61% of those with a high-school (or less) education read books; 89% of college graduates read books.

According to PEW, the average reader manages twelve a year.

There is some evidence that reading is a declining habit: according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, average time spent reading for pleasure declined from twenty-three minutes a day to seventeen minutes a day from 2005 to 2017. But the least decline was among young adults, 18 to 34 (less than 1%).

In fact, there is good evidence that the much-maligned millennials read more than their parents, and they overwhelmingly prefer hard copies to digital books. Even better, the millennials pay for their books:

April 28, 2022

QotD: The NFL Draft

NFL scouts can (and do) measure just about everything about a prospect prior to the draft, but they can’t quantifiably measure heart and leadership, two of the most important yet undervalued skills a quarterback can possess.

Every year they draft these big, strong, good-looking guys that can chuck it a country mile. And three years later they turn out to be Joey Harrington or Tim Couch or Jeff George or some other bust who couldn’t lead a hungry lineman to free barbeque, let alone an entire team to a championship.

Dan Wetzel, “Follow the Leader”, Yahoo! Sports, 2006-04-27.

February 4, 2022

“In particular, he noted that as you stretch out the models across time ‘the errors increase radically'”

At the Daily Sceptic, Chris Morrison notes that Canadians have become omnipresent on Joe Rogan’s podcast recently:

It’s been all Canada on Joe Rogan’s popular Spotify podcast of late. First, crinkly rockers Neil and Joni threw their guitars out of the pram when Rogan dared to broadcast a number of different opinions on Covid and vaccines. Then fellow Canadian Dr. Jordan Peterson said climate models compounded their errors, just like interest. Green activists and zealots (often known in the climate change business as “scientists”) clutched their responsibly sourced pearls and whined, “Lawks a-mercy, it’s outrageous!” and “Banning’s too good for them!”. The septuagenarian songsters briefly found themselves out of the headlines as the mainstream media rushed to quell a growing sceptical climate debate and rubbish a troublesome competitor.

Dr. Peterson suggested that the climate was too complex to be modelled. Such notions were said to be a “word salad of nonsense”, reported a distraught Guardian. Dr. Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick of the University of Canberra added Peterson had “no frickin’ idea”. Professor Michal Mann of Penn State University said Peterson’s comments – and Rogan’s “facilitation” of them – was an “almost comedic type of nihilism” that would be funny if it wasn’t so dangerous.

This of course is the same Michael Mann who produced the infamous temperature hockey stick that was at the centre of the 2010 Climategate scandal. The graph was used for a time in IPCC reports and showed a 1,000 year straight temperature line followed by a recent dramatic rise. This startling image was helped by the mysterious disappearance of the medieval warming period and subsequent little ice age. Discussion about the graph led to Mann pursuing a U.S. libel suit against the broadcaster and journalist Mark Steyn. In court filings, Mann argued that it was one thing to engage in discussion about debatable topics, but it was quite another to “attempt to discredit consistently validated scientific research through the professional and personal defamation of a Nobel Prize recipient”. He is not himself a Nobel Prize recipient, but perhaps he was referring to someone else.

Independent minded communicators like Joe Rogan and take-no-prisoner intellectuals such as Dr. Peterson command a worldwide audience and they are difficult to cancel. The battle between Neil Young and Joni Mitchell and Joe Rogan, sitting on a $100m Spotify contract, had only one free speech winner – at least for the moment. Meanwhile, the Guardian‘s default position when faced with something unsettling like the “settled” science of anthropogenic climate change is to declare it will not “lend” its credibility to its critics by engaging in debate. That was obviously not possible with Peterson’s remarks being plastered all over social media, although it could be argued that the Guardian reporting the vulgar abuse users posted in response is not much of a substitute for the usual lofty disdain.

Dr. Peterson attacked climate models on a number of fronts. In particular, he noted that as you stretch out the models across time “the errors increase radically”. In its way, this refers to the biggest problem that lies at the heart of the 40-year track record of climate model failures. To make a prediction, climate models are fed a guess of the increase in the global mean surface temperature that follows a doubling of atmospheric CO2. Nobody actually knows what this figure is – the science for this crucial piece of the jigsaw is missing, unsettled you may say. The estimates run from 1°C to as high as 6°C and of course the higher the estimate, the hotter the forecasts run.

As they don’t say in the climate and Covid modelling business – Garbage In, Garbage Out.

January 22, 2022

“China’s statistics remain in the hands of officials who carefully do everything possible to make sure China’s image remains unblemished”

I’ve been a disbeliever in official Chinese statistics for many years — one of the first repeat topics on the blog in 2004 was the unreliable nature of Chinese government statistics on economic growth. As a result, I find it very easy to believe that the Chinese statistics on deaths due to the Wuhan Coronavirus pandemic are unreliable, as John Horvat explains:

As the latest wave of COVID cases surges in the West, all is quiet in the East. It has always been quiet. Millions have died from the coronavirus epidemic as it sweeps the world. However, few consider it strange that the nation where the virus first appeared amid an entirely unprotected public of 1.3 billion people should record a mere 4,636 fatalities over the past three years.

China’s statistics remain in the hands of officials who carefully do everything possible to make sure China’s image remains unblemished. They claim that low numbers are due to the communist nation’s brutal “zero tolerance” policies. China is presented as a model for the West.

Some voices are appearing that dispute this claim. One expert says the fatality figures are likely closer to 1.7 million. This figure would put China in the same camp as the rest of the world. It would also point to the failure of the world’s strictest lockdown and explain the recent shutdowns of whole cities and regions due to the virus, which supposedly kills no one in China.

[…]

Communist parties have always used statistics as a tool and weapon to advance their agenda. Officials feel free to change the numbers to reflect well upon the state, which controls everything. Truth is whatever furthers the fortunes of the party. If statistics must be changed as a result, there is no problem. Hence the notorious unreliability of communist statistics.

The problem is complicated by anxious officials who must report good news to party leaders or face the consequences of their failures, including death. Zero tolerance numbers may be statistically impossible and even absurd, but most officials prefer their survival over inconvenient truths.

Also disturbing is the complicity of Western media that repeat the cooked numbers of communist regimes. Few dare to question impossible figures or “follow the science” when leftist prestige is involved. During the long Cold War, the West presented the Soviet Union as the second-largest economy. When the Berlin Wall fell, the actual size of the economy was found to be significantly less.

Even in a centrally planned socialist state, incentives matter. In the west, failing to meet expected standards may get you fired (unless you work for the government), but in authoritarian states like China it can get you shot or exiled to a remote labour camp for years or decades. The top statisticians know that the numbers they work on are … massaged … at every stage even before they are aggregated for regional or national reporting, but there is literally no point in telling the truth and there is much to be gained by “scenario-ing them rosily” because your bosses will only accept good news regardless of reality.